Economic inequality

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Economics

Economic inequality refers to disparities in the distribution of economic assets and income. The term typically refers to inequality among individuals and groups within a society, but can also refer to inequality among nations. Economic Inequality generally refers to equality of outcome, and is related to the idea of equality of opportunity. It is a contested issue whether economic inequality is a positive or negative phenomenon, both on utilitarian and moral grounds.

Economic inequality has existed in a wide range of societies and historical periods; its nature, cause and importance are open to broad debate. A country's economic structure or system (for example, capitalism or socialism), ongoing or past wars, and differences in individuals' abilities to create wealth are all involved in the creation of economic inequality.

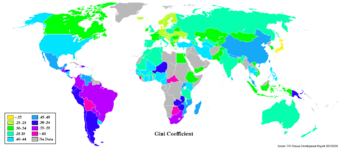

There are various Numerical indexes for measuring economic inequality. Inequality is most often measured using the Gini coefficient, but there are also many other methods. One way to measure inequality is money based. For instance a person may be regarded as poor if their income falls below the line of poverty.

Economic inequality among different individuals or social groups is best measured within a single country. This is because country-specific factors tend to obscure inter-country comparisons of individuals' incomes. A single nation will have more or less inequality depending on the social and economic structure of that country.

Causes of inequality

There are many reasons for economic inequality within societies. These causes are often inter-related, non-linear, and complex. Acknowledged factors that impact economic inequality include the labour market, innate ability, education, race, gender, culture, preference for earning income or enjoying leisure, willingness to take risks, wealth condensation, and development patterns.

The labor market

A major cause of economic inequality within modern market economies is the determination of wages by the market, provided, that this market is a free market ruled only by the law of supply and demand. In this view, inequality is caused by the differences in the supply and demand for different types of work.

A job where there are many willing workers (high supply) but only a small number of positions (low demand) will result in a low wage for that job. This is because competition between workers drives down the wage. An example of this would be low-skill jobs such as dish-washing or customer service. Because of the persistence of unemployment in market economies and the fact that these jobs require very little skill results in a very high supply of willing workers. Competition amongst workers tend to drive down the wage since if any one worker demands a higher wage the employer can simply hire another employee at an equally low wage.

A job where there are few willing workers (low supply) but a large demand for the skills these workers have will results in high wages for that job. This is because competition between employers will drive up the wage. An example of this would be high-skill jobs such as engineers, professional athletes, or capable CEOs. Competition amongst employers tends to drive up wages since if any one employer demands a low wage, the worker can simply quit and easily find a new job at a higher wage.

While the above examples tend to identify skill with high demand and wages, this is not necessarily the case. For example, highly skilled computer programmers in western countries have seen their wages suppressed by competition from computer programmers in Developing Countries who are willing to accept a lower wage.

The final results amongst these supply and demand interactions is a gradation of different wages representing income inequality within society.

Innate ability

Many people believe that there is a correlation between differences in innate ability, such as intelligence, strength, or charisma, and an individual's wealth. Relating these innate abilities back to the labor market suggests that such abilities are in high demand relative to their supply and hence play a large role in increasing the wage of those who have them. Contrariwise, such innate abilities might also affect an individuals ability to operate within society in general, regardless of the labor market.

Various studies have been conducted on the correlation between IQ scores and wealth/income. The book titled " IQ and the Wealth of Nations", written by Dr. Richard Lynn, examines this relationship with limited success; other peer-reviewed research papers have also been criticised harshly. Without further research on the topic, incorporating statistical models that are universally accepted, it is fairly difficult to come towards an objective conclusion regarding any relationship between intelligence and wealth or income.

Education

One important factor in the creation of inequality is variation in individuals' access to education. Education, especially in an area where there is a high demand for workers, creates high wages for those with this education. As a result, those who are unable to afford an education, or choose not to pursue optional education, generally receive much lower wages. Many economists believe that a major reason the world has experienced increasing levels of inequality since the 1980s is an increase in the demand for highly skilled workers in high-tech industries. They believe that this has resulted in an increase in wages for those with an education, but has not increased the wages of those without an education, leading to greater inequality.

Gender, race, and culture

The existence of different genders, races and cultures within a society is also thought to contribute to economic inequality. Some psychologists such as Richard Lynn argue that there are innate group differences in ability that are partially responsible for producing race and gender group differences in wealth (see also race and intelligence, sex and intelligence) though this assertion is highly controversial.

The idea of the gender gap tries to explain differences in income between genders. Culture and religion are thought to play a role in creating inequality by either encouraging or discouraging wealth-acquiring behaviour, and by providing a basis for discrimination. In many countries individuals belonging to certain racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to be poor. Proposed causes include cultural differences amongst different races, an educational achievement gap, and racism.

Development patterns

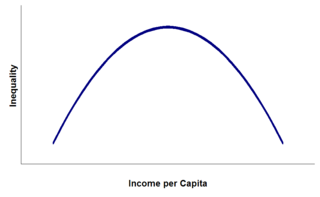

Simon Kuznets argued that levels of economic inequality are in large part the result of stages of development. Kuznets saw a curve-like relationship between level of income and inequality, now known as Kuznets curve. According to Kuznet, countries with low levels of development have relatively equal distributions of wealth. As a country develops, it acquires more capital, which leads to the owners of this capital having more wealth and income and introducing inequality. Eventually, through various possible redistribution mechanisms such as social welfare programs, more developed countries move back to lower levels of inequality. Kuznets demonstrated this relationship using cross-sectional data. However, more recent testing of this theory with superior panel data has shown it to be very weak.

Wealth condensation

Wealth condensation is a theoretical process by which, under certain conditions, newly-created wealth concentrates in the possession of already-wealthy individuals or entities. According to this theory, those who already hold wealth have the means to invest in new sources of creating wealth or to otherwise leverage the accumulation of wealth, thus are the beneficiaries of the new wealth. Over time, wealth condensation can significantly contribute to the persistence of inequality within society.

As an example of wealth condensation, truck drivers who own their own trucks often make more money than those who do not, since the owner of a truck can escape the rent charged to drivers by owners (even taking into account maintenance and other costs). Hence, a truck driver who has wealth to begin with can afford to buy his own truck in order to make more money. A truck driver who does not own his own truck makes a lesser wage and is therefore stuck in a Catch-22, unable to buy his own truck to increase his income.

As another example of wealth condensation, savings from the upper-income groups tend to accumulate much faster than saving from the lower-income groups. Upper-income groups can save a significant portion of their incomes. On the other hand, lower-income groups barely make enough to cover their consumptions, hence only capable of saving a fraction of their incomes or even none. Assuming both groups earn the same yield rate on their savings, the return on upper-income groups’ savings are much greater than the lower-income groups’ savings because upper-income groups have a much larger base.

Related to wealth condensation are the effects of intergenerational inequality. The rich tend to provide their offspring with a better education, increasing their chances of achieving a high income. Furthermore, the wealthy often leave their offspring with a hefty inheritance, jump-starting the process of wealth condensation for the next generation. However, it has been contended by some sociologists such as Charles Murray that this has little effect on one's long-term outcome and that innate ability is by far the best determinant of one's lifetime outcome.

Globalisation

Trade liberalisation may shift economic inequality from a global to a domestic scale. When rich countries trade with poor countries, the low-skilled workers in the rich countries may see reduced wages as a result of the competition. Trade economist Paul Krugman estimates that trade liberalisation has had a measurable effect on the rising inequality in the United States. He attributes this trend to increased trade with poor countries and the fragmentation of the means of production, resulting in low skilled jobs becoming more tradeable. However, he concedes that the effect of trade on inequality in America is minor when compared to other causes, such as technological innovation, a view shared by other experts. Lawrence Katz, a Harvard economist, estimates that trade has only accounted for 5-15% of rising income inequality. Some economists, such as Robert Lawrence, dispute any such relationship. In particular, Robert Lawrence argues that technological innovation and automation has meant that low-skilled jobs have been replaced by machines in rich countries, and that rich countries no longer have significant numbers of low skilled manufacturing workers that could be affected by competition from poor countries.

Mitigating factors

There are many factors that tend to constrain the amount of economic inequality within society. These factors may be divided into two general classes: government sponsored, and market driven. The relative merits and effectiveness of each approach is a subject of heated debate.

Proponents of government sponsored approaches to reducing economic inequality generally believe that economic inequality represents a fundamental injustice, and that it is the right and duty of the government to correct this injustice. Government sponsored approaches to reducing economic inequality include:

- Mass education - to increase the supply of skilled labor and decrease the wage of skilled labour to reduce income inequality;

- Progressive taxation, where the rich are taxed more than the poor - to reduce the amount of income inequality in society.

- Minimum wage legislation - to raise the income of the poorest working group. However, proponents of the free market point out this will cut the least skilled out of the employment market entirely.

- The Nationalization or subsidization of "essential" goods and services such as food, healthcare, education, and housing - to reduce the amount of inequality in society - by providing goods and services that everyone needs cheaply or freely, governments can effectively increase the disposable income of the poorer members of society.

Proponents of free markets point out that these measures usually backfire, as the growth of government would create a privileged class such as the nomenklatura in the Soviet Union who use their position within the government to gain unequal access to resources, thereby reducing economic equality. Others argue that free markets without these measures allow the already privileged to control the political life of a country as it did in Brazil where the country's right wing military dictatorship (1964-1985) allowed the country to become the most economically unequal in South America.

Other proponents of free markets do not generally see economic inequality in a free market as fundamentally unjust. Market-driven reductions in economic inequality are therefore incidental to economic freedom. Nevertheless there are some market forces which work to reduce economic inequality:

- In a market-driven economy, too much economic disparity could generate pressure for its own removal. In an extreme example, if one person owned everything, that person would immediately (in a market economy) have to hire people to maintain his property, and that person's wealth would immediately begin to dissipate. (García-Peñalosa 2006)

- By a concept known as the "decreasing marginal utility of wealth," a wealthy person will tend not to value his last dollar as much as a poor person, since a poor person's dollars are more likely to be spent for essentials. This could tend to move wealth from the rich to the poor. A derogatory term for this is the " trickle down effect."

Effects of inequality

Social cohesion

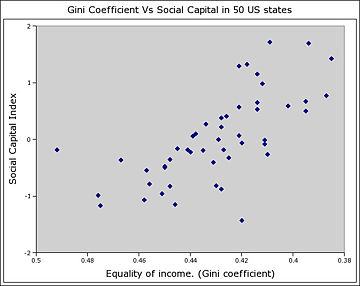

Research has shown a clear link between income inequality and social cohesion. In more equal societies, people are much more likely to trust each other, measures of social capital suggest greater community involvement, and homicide rates are consistently lower.

One of the earliest writers to note the link between economic equality and social cohesion was Alexis de Tocqueville in his Democracy in America. Writing in 1831:

- Among the new objects that attracted my attention during my stay in the United States, none struck me with greater force than the equality of conditions. I easily perceived the enormous influence that this primary fact exercises on the workings of society. It gives a particular direction to the public mind, a particular turn to the laws, new maxims to those who govern, and particular habits to the governed... It creates opinions, gives rise to sentiments, inspires customs, and modifies everything it does not produce... I kept finding that fact before me again and again as a central point to which all of my observations were leading.

In a 2002 paper, Eric Uslaner and Mitchell Brown showed that there is a high correlation between the amount of trust in society and the amount of income equality. They did this by comparing results from the question "would others take advantage of you if they got the chance?" in U.S General Social Survey and others with statistics on income inequality.

Robert Putnam, professor of political science at Harvard, established links between social capital and economic inequality. His most important studies (Putnam, Leonardi, and Nanetti 1993, Putnam 2000) established these links in both the United States and in Italy. On the relationship of inequality and involvement in community he says:

- Community and equality are mutually reinforcing… Social capital and economic inequality moved in tandem through most of the twentieth century. In terms of the distribution of wealth and income, America in the 1950s and 1960s was more egalitarian than it had been in more than a century… [T]hose same decades were also the high point of social connectedness and civic engagement. Record highs in equality and social capital coincided. Conversely, the last third of the twentieth century was a time of growing inequality and eroding social capital… The timing of the two trends is striking: somewhere around 1965-70 America reversed course and started becoming both less just economically and less well connected socially and politically. (Putnam 2000 pp 359)

In addition to affecting levels of trust and civic engagement, inequality in society has also shown to be highly correlated with crime rates. Most studies looking into the relationship between crime and inequality have concentrated on homicides - since homicides are almost identically defined across all nations and jurisdictions. There have been over fifty studies showing tendencies for violence to be more common in societies where income differences are larger. Research has been conducted comparing developed countries with undeveloped countries, as well as studying areas within countries. Daly et al. 2001. found that among U.S States and Canadian Provinces there is a tenfold difference in homicide rates related to inequality. They estimated that about half of all variation in homicide rates can be accounted for by differences in the amount of inequality in each province or state. Fajnzylber et al. (2002) found a similar relationship worldwide. Among comments in academic literature on the relationship between homicides and inequality are:

- The most consistent finding in cross-national research on homicides has been that of a positive association between income inequality and homicides. (Neapolitan 1999 pp 260)

- Economic inequality is positively and significantly related to rates of homicide despite an extensive list of conceptually relevant controls. The fact that this relationship is found with the most recent data and using a different measure of economic inequality from previous research, suggests that the finding is very robust. (Lee and Bankston 1999 pp 50)

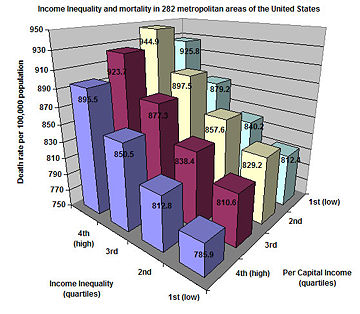

Population health

Recently, there has been increasing interest from epidemiologists on the subject of economic inequality and its relation to the health of populations. There is a very robust correlation between socioeconomic status and health. This correlation suggests that it is not only the poor who tend to be sick when everyone else is healthy, but that there is a continual gradient, from the top to the bottom of the socio-economic ladder, relating status to health. This phenomenon is often called the " SES Gradient". Lower socioeconomic status has been linked to chronic stress, heart disease, ulcers, type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, certain types of cancer, and premature aging.

There is debate regarding the cause of the SES Gradient. A number of researchers (A. Leigh, C. Jencks, A. Clarkwest - see also Russell Sage working papers) see a definite link between economic status and mortality due to the greater economic resources of the wealthy, but they find little correlation due to social status differences.

Other researchers such as Richard Wilkinson, J. Lynch, and G.A. Kaplan have found that socioeconomic status strongly affects health even when controlling for economic resources and access to health care. Most famous for linking social status with health are the Whitehall studies - a series of studies conducted on civil servants in London. The studies found that although all civil servants in England have the same access to health care, there was a strong correlation between social status and health. The studies found that this relationship remained strong even when controlling for health-affecting habits such as exercise, smoking and drinking. Furthermore, it has been noted that no amount of medical attention will help decrease the likelihood of someone getting type 2 diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis - yet both are more common among populations with lower socioeconomic status. Lastly, it has been found that amongst the wealthiest quarter of countries on earth (a set stretching from Luxembourg to Slovakia) there is no relation between a country's wealth and general population health - suggesting that past a certain level, absolute levels of wealth have little impact on population health, but relative levels within a country do.

The concept of psychosocial stress attempts to explain how psychosocial phenomena such as status and social stratification can lead to the many diseases associated with the SES Gradient. Higher levels of economic inequality tend to intensify social hierarchies and generally degrade the quality of social relations - leading to greater levels of stress and stress-related diseases. Richard Wilkinson found this to be true not only for the poorest members of society, but also for the wealthiest. Economic inequality is bad for everyone's health.

The effects of inequality on health are not limited to human populations. David H. Abbott at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Centre found that among many primate species, less egalitarian social structures correlated with higher levels of stress hormones among socially subordinate individuals.

Utility, economic welfare, and distributive efficiency

Economic inequality is thought to reduce distributive efficiency within society. That is to say, inequality reduces the sum total of personal utility because of the decreasing marginal utility of wealth. For example, a house may provide less utility to a single millionaire as a summer home than it would to a homeless family of five. The marginal utility of wealth is lowest among the richest. In other words, an additional dollar spent by a poor person will go to things providing a great deal of utility to that person, such as basic necessities like food, water, and healthcare; meanwhile, an additional dollar spent by a much richer person will most likely go to things providing relatively less utility to that person, such as luxury items. From this standpoint, for any given amount of wealth in society, a society with more equality will have higher aggregate utility. Some studies (Layard 2003;Blanchard and Oswald 2000, 2003) have found evidence for this theory, noting that in societies where inequality is lower, population-wide satisfaction and happiness tend to be higher.

Economist Arthur Cecil Pigou discussed the impact of inequality in The Economics of Welfare. He wrote:

Nevertheless, it is evident that any transference of income from a relatively rich man to a relatively poor man of similar temperament, since it enables more intense wants, to be satisfied at the expense of less intense wants, must increase the aggregate sum of satisfaction. The old "law of diminishing utility" thus leads securely to the proposition: Any cause which increases the absolute share of real income in the hands of the poor, provided that it does not lead to a contraction in the size of the national dividend from any point of view, will, in general, increase economic welfare.

In addition to the argument based on diminishing marginal utility, Pigou makes a second argument that income generally benefits the rich by making them wealthier than other people, whereas the poor benefit in absolute terms. Pigou writes:

Now the part played by comparative, as distinguished from absolute, income is likely to be small for incomes that only suffice to provide the necessaries and primary comforts of life, but to be large with large incomes. In other words, a larger proportion of the satisfaction yielded by the incomes of rich people comes from their relative, rather than from their absolute, amount. This part of it will not be destroyed if the incomes of all rich people are diminished together. The loss of economic welfare suffered by the rich when command over resources is transferred from them to the poor will, therefore, be substantially smaller relatively to the gain of economic welfare to the poor than a consideration of the law of diminishing utility taken by itself suggests. -- Arthur Cecil Pigou in The Economics of Welfare

Schmidtz (2006) argues that maximizing the sum of individual utilities does not necessarily imply that the maximum social utility is achieved. For example:

A society that takes Joe Rich’s second unit [of corn] is taking that unit away from someone who . . . has nothing better to do than plant it and giving it to someone who . . . does have something better to do with it. That sounds good, but in the process, the society takes seed corn out of production and diverts it to food, thereby cannibalizing itself

Economic incentives

Many people accept inequality as a given, and argue that the prospect of greater material wealth provides incentives for competition and innovation within an economy.

Some modern economic theories, such as the neoclassical school, have suggested that a functioning economy requires a certain level of unemployment. These theories argue that unemployment benefits must be below the wage level to provide an incentive to work, thereby mandating inequality. Hypotheses including socialism and Keynesianism, dispute this positive role of unemployment.

Many economists believe that one of the main reasons that inequality might induce economic incentive is because material wellbeing and conspicuous consumption are related to status. In this view, high stratification of income (high inequality) creates high amounts of social stratification, leading to greater competition for status. One of the first writers to note this relationship was Adam Smith who recognized "regard" as one of the major driving forces behind economic activity. From The Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759:

- [W]hat is the end of avarice and ambition, of the pursuit of wealth, of power, and pre-eminence? Is it to supply the necessities of nature? The wages of the meanest labourer can supply them... [W]hy should those who have been educated in the higher ranks of life, regard it as worse than death, to be reduced to live, even without labour, upon the same simple fare with him, to dwell under the same lowly roof, and to be clothed in the same humble attire? From whence, then, arises that emulation which runs through all the different ranks of men, and what are the advantages which we propose by that great purpose of human life which we call bettering our condition? To be observed, to be attended to, to be taken notice of with sympathy, complacency, and approbation, are all the advantages which we can propose to derive from it. It is the vanity, not the ease, or the pleasure, which interests us ( Theory of Moral Sentiments, Part I, Section III, Chapter II).

Modern sociologists and economists such as Juliet Schor and Robert H. Frank have studied the extent to which economic activity is fueled by the ability of consumption to represent social status. Schor, in The Overspent American, argues that the increasing inequality during the 1980s and 1990s strongly accounts for increasing aspirations of income, increased consumption, decreased savings, and increased debt. In Luxury Fever Robert H. Frank argues that people's satisfaction with their income is much more strongly affected by how it compares with others than its absolute level.

Economic growth

Several recent economists have investigated the relationship between inequality and economic growth using econometrics.

In their study for the World Institute for Development Economics Research, Giovanni Andrea Cornia and Julius Court (2001) reach policy conclusions as to the optimal distribution of income. They conclude that too much equality (below a Gini coefficient of .25) negatively impacts growth due to "incentive traps, free-riding, labour shirking, [and] high supervision costs". They also claim that high levels of inequality (above a Gini coefficient of .40) negatively impacts growth, due to "incentive traps, erosion of social cohesion, social conflicts, [and] uncertain property rights". They advocate for policies which put equality at the low end of this "efficient" range.

Robert Barro wrote a paper arguing that inequality reduces growth in poor countries and promotes growth in rich ones. A number of other researchers have derived conflicting results, some concluding there is a negative effect of inequality on growth and others a positive. Patrizio Pagano used Granger causality, a technique that can determine two way interaction between two variables, to attempt to explain these previous findings. Pagano's research suggested that inequality had a negative effect on growth while growth increased inequality. The two-way interaction largely explains the contradiction in past research.

Perspectives regarding economic inequality

There are various schools of thought regarding economic inequality.

Marxism

Marxism favors an eventual society where distribution is based on an individual's needs rather than his ability to produce, social class, inheritance, or other such factors. In such a system inequality would be low or non-existent assuming everyone had the same "needs".

Meritocracy

Meritocracy favors an eventual society where an individual's success is a direct function of his merit, or contribution. Therefore, economic inequality is beneficial inasmuch as it reflects individual skills and effort, and detrimental inasmuch as it represent inherited or unjustified wealth or opportunities. From a meritocratic point of view, measuring economic equality as one parameter, not distinguishing these two opposite contributing factors, serves no good purpose.

Liberalism

Classical liberals and libertarians generally do not take a stance on wealth inequality, but believe in equality under the law regardless of whether it leads to unequal wealth distribution. Ludwig von Mises (1996) explains:

The liberal champions of equality under the law were fully aware of the fact that men are born unequal and that it is precisely their inequality that generates social cooperation and civilization. Equality under the law was in their opinion not designed to correct the inexorable facts of the universe and to make natural inequality disappear. It was, on the contrary, the device to secure for the whole of mankind the maximum of benefits it can derive from it. Henceforth no man-made institutions should prevent a man from attaining that station in which he can best serve his fellow citizens.

Libertarian Robert Nozick argued that government redistributes wealth by force (usually in the form of taxation), and that the ideal moral society would be one where all individuals are free from force. However, Nozick recognized that some modern economic inequalities were the result of forceful taking of property, and a certain amount of redistribution would be justified to compensate for this force but not because of the inequalities themselves. John Rawls argued in A Theory of Justice that inequalities in the distribution of wealth are only justified when they improve society as a whole, including the poorest members. Rawls does not discuss the full implications of his theory of justice. Some see Rawls's argument as a justification for capitalism since even the poorest members of society theoretically benefit from increased innovations under capitalism; others believe only a strong welfare state can satisfy Rawls's theory of justice.

Classical liberal Milton Friedman believed that if government action is taken in pursuit of economic equality that political freedom would suffer. In a famous quote, he said:

- A society that puts equality before freedom will get neither. A society that puts freedom before equality will get a high degree of both.

Arguments based on social justice

Patrick Diamond and Anthony Giddens (professors of Economics and Sociology, respectively) hold that

pure meritocracy is incoherent because, without redistribution, one generation's successful individuals would become the next generation's embedded caste, hoarding the wealth they had accumulated.

They also state that social justice requires redistribution of high incomes and large concentrations of wealth in a way that spreads it more widely, in order to "recognise the contribution made by all sections of the community to building the nation's wealth." (Patrick Diamond and Anthony Giddens, 27 June 2005, New Statesman)

Claims economic inequality weakens societies

In most western democracies, the desire to eliminate or reduce economic inequality is generally associated with the political left. One practical argument in favour of reduction is the idea that economic inequality reduces social cohesion and increases social unrest, thereby weakening the society.

There is evidence that this is true (see inequity aversion) and it is intuitive, at least for small face-to-face groups of people. Alberto Alesina, Rafael Di Tella, and Robert MacCulloch find that inequality negatively affects happiness in Europe but not in the United States.

Ricardo Nicolás Pérez Truglia in "Can a rise in income inequality improve welfare?" proposed a possible explanation: some goods might not be allocated through standard markets, but through a signaling mechanism. As long as income is associated with positive personal traits (e.g. charisma), in more heterogeneous-in-income societies income not only buys traditional goods (e.g. food, a house), but it also buys non-market goods (e.g. friends, confidence). Thus, endogenous income inequality may explain a rise in social welfare.

It has also been argued that economic inequality invariably translates to political inequality, which further aggravates the problem.

The main disagreement between the western democratic left and right, is basically a disagreement on the importance of each effect, and where the proper balance point should be. Both sides generally agree that the causes of economic inequality based on non-economic differences (race, gender, etc.) should be minimized. There is strong disagreement on how this minimization should be achieved.

Arguments that inequality is not a primary concern

The acceptance of economic inequality is generally associated with the political right. One argument in favor of the acceptance of economic inequality is that, as long as the cause is mainly due to differences in behavior, the inequality provides incentives that push the society towards economically healthy and efficient behaviour. Capitalists see orderly competition and individual initiative as crucial to economic prosperity and accordingly believe that economic freedom is more important than economic equality.

Policy can be considered good if it makes some wealthy people wealthier without making anyone poorer (i.e. a policy which offers a Pareto improvement), even though it increases the total amount of inequality. According to this point of view, discussions of inequality absent any information about absolute levels of wealth are specious, because one population's "poor" may be better off that another's "well-off."

A third argument is that capitalism, especially free market capitalism, results in voluntary transactions among parties. Since the transactions are voluntary, each party at least believes they benefit from the transaction. According to the subjective theory of value, both parties will indeed benefit the transaction (assuming there is no fraud or extortion involved).