Elementary group theory

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Mathematics

In mathematics, a group ⟨G,*⟩ is defined as a set G and a binary operation on G, called product and denoted by infix "*". Product obeys the following rules (also called axioms). Let a, b, and c be arbitrary elements of G. Then:

- A1, Closure. a*b is in G;

- A2, Associativity. (a*b)*c=a*(b*c);

- A3, Identity. There exists an identity element e in G such that a*e=e*a=a. e, the identity of G, is unique by Theorem 1.4 below;

- A4, Inverse. For each a in G, there exists an inverse element x in G such that a*x=x*a=e. x, the inverse of a, is unique by Theorem 1.5 below.

An abelian group also obeys the additional rule:

- A5, Commutativity. a*b = b*a.

Closure is part of the definition of "binary operation," so that A1 is often omitted.

Elaboration

- Group product "*" is not necessarily multiplication. Addition works just as well, as do many less standard operations.

- When * is a standard operation, we use the standard symbol instead (for example, + for addition).

- When * is addition or any commutative operation (except multiplication), 0 usually denotes the identity and -a denotes the inverse of a. The operation is always denoted by something other than * -- often + -- to avoid confusion with multiplication.

- When * is multiplication or a noncommutative operation,a*b is often written ab. 1 usually denotes the identity element, and a -1 usually denotes the inverse of a.

- The group ⟨G,*⟩ is often referred to as "the group G" or simply "G"; but the operation "*" is fundamental to the description of the group.

- ⟨G,*⟩ is usually pronounced "the group G under *". When affirming that G is a group (for example, in a theorem), we say that "G is a group under *".

Examples

G={1,-1} is a group under multiplication, because for all elements a, b, c in G:

- A1: a*b is an element of G.

- A2: (a*b)*c=a*(b*c) can be verified by enumerating all 8 possible (and trivial) cases.

- A3: a*1=a. Hence 1 is an identity element.

- A4: a-1*a=1. Hence a-1 denotes inverse and 1 is an inverse element.

- A2: (a*b)*c=a*(b*c) can be verified by enumerating all 8 possible (and trivial) cases.

The integers Z and the real numbers R are groups under addition '+'. For all elements a, b, and c of either Z or R:

- A1: Adding any two numbers yields another number of the same kind.

- A2: (a+b)+c=a+(b+c).

- A3: a+0=a. Hence 0 is an identity element.

- A4: -a+a=0. Hence -a denotes inverse and 0 is an inverse element.

- A2: (a+b)+c=a+(b+c).

The real numbers R are NOT a group under multiplication '*'. For all a, b, and c in R:

- A3: 1.

- A4: 0*a=0, so 0 has no inverse.

The real numbers without 0, R#, are a group under multiplication '*'.

- A1: Multiplying any two elements of R# yields another element of R#.

- A2: (a*b)*c=a*(b*c).

- A3: a*1=a. Hence 1 denotes identity.

- A4: a -1*a=1. Hence a -1 denotes inverse.

- A2: (a*b)*c=a*(b*c).

Alternative Axioms

A3 and A4 can be replaced by:

- A3’, left neutral. There exists an e in G such that for all a in G, e*a=a.

- A4’, left inverse. For each a in G, there exists an element x in G such that x*a=e.

Or alternatively by:

- A3’’, right neutral. There exists an e in G such that for all a in G, a*e=a.

- A4’’, right inverse. For each a in G, there exists an element x in G such that a*x=e.

These apparently weaker pairs of axioms are naturally implied by A3 and A4. We will now show that the converse is true.

Theorem: Assuming A1 and A2, A3’ and A4’ imply A3 and A4.

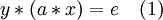

Proof. Let a left neutral element e be given, and a in G. By A4’ there exist an x such that a*x=e. We show that also x*a**=e. Per A4’ there is an y in G with:

Therefore:

This establishes A4.

This establishes A3.

Theorem: Assuming A1 and A2, A3’’ and A4’’ imply A3 and A4.

Proof. Similar to the above.

Basic theorems

Identity is unique

Theorem 1.4: The identity element of a group ⟨G,*⟩ is unique.

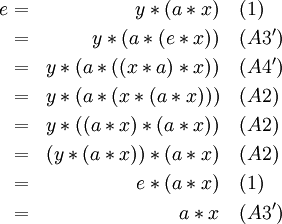

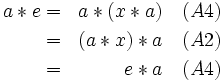

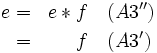

Proof: Suppose that e and f are two identity elements of G. Then

As a result, we can speak of the identity element of ⟨G,*⟩ rather than an identity element. Where different groups are being discussed and compared, eG denotes the identity of the specific group ⟨G,*⟩.

Inverses are unique

Theorem 1.5: The inverse of each element in ⟨G,*⟩ is unique.

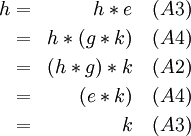

Proof: Suppose that h and k are two inverses of an element g of G. Then

As a result, we can speak of the inverse of an element a, rather than an inverse. Without ambiguity, for all a in G, we denote by a -1 the unique inverse of a.

Latin square property

Theorem 1.3: For all elements a,b in G, there exists a unique x in G such that a*x = b.

Proof. At least one such x surely exists, for if we let x = a -1*b, then x is in G (by A1, closure) and:

- a*x = a*(a -1*b) (substituting for x)

- a*(a -1*b) = (a*a -1)*b (associativity A2).

- (a*a -1)*b= e*b = b. (identity A3).

- Thus an x always exists satisfying a*x = b.

To show that this is unique, if a*x=b, then

- x = e*x

- e*x = (a -1*a)*x

- (a -1*a)*x = a -1*(a*x)

- a -1*(a*x) = a -1*b

- Thus, x = a -1*b

Similarly, for all a,b in G, there exists a unique y in G such that y*a = b.

Inverting twice gets you back where you started

Theorem 1.6: For all elements a in group G, (a -1) -1=a.

Proof. a -1*a = e. The conclusion follows from Theorem 1.4.

Inverse of ab

Theorem 1.7: For all elements a,b in group G, (a*b) -1=b -1*a -1.

Proof. (a*b)*(b -1*a -1) = a*(b*b -1)*a -1 = a*e*a -1 = a*a -1 = e. The conclusion follows from Theorem 1.4.

Cancellation

Theorem 1.8: For all elements a,x, and y in group G, if a*x=a*y, then x=y; and if x*a=y*a, then x=y.

Proof. If a*x = a*y then:

- a -1*(a*x) = a -1*(a*y)

- (a -1*a)*x = (a -1*a)*y

- e*x = e*y

- x = y

If x*a = y*a then

- (x*a)*a -1 = (y*a)*a -1

- x*(a*a -1) = y*(a*a -1)

- x*e = y*e

- x = y

Powers

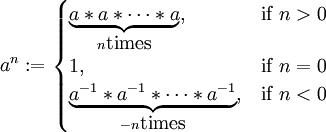

For  and

and  we define:

we define:

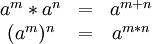

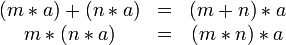

Theorem 1.9: For all a in group ⟨G,*⟩,  :

:

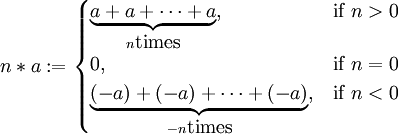

Similarly if G is written in additive notation, we have:

and:

Order

Of a group element

The order of an element a in a group G is the least positive integer n such that an = e. Sometimes this is written "o(a)=n". n can be infinite.

Theorem 1.10: A group whose nontrivial elements all have order 2 is abelian. In other words, if all elements g in a group G g*g=e is the case, then for all elements a,b in G, a*b=b*a.

Proof. Let a, h be any 2 elements in the group G. By A1, a*h is also a member of G. Using the given condition, we know that (a*h)*(a*h)=e. Hence:

- a*(a*b)*(a*b) = a*e

- a*(a*b)*(a*b)*b = a*e*b

- (a*a)*(b*a)*(b*b) = (a*e)*b

- e*(b*a)*e = a*b

- b*a = a*b.

Since the group operation * commutes, the group is abelian

Of a group

The order of the group G, usually denoted by |G| or occasionally by o(G), is the number of elements in the set G, in which case ⟨G,*⟩ is a finite group. If G is an infinite set, then the group ⟨G,*⟩ has order equal to the cardinality of G, and is an infinite group.

Subgroups

A subset H of G is called a subgroup of a group ⟨G,*⟩ if H satisfies the axioms of a group, using the same operator "*", and restricted to the subset H. Thus if H is a subgroup of ⟨G,*⟩, then ⟨H,*⟩ is also a group, and obeys the above theorems, restricted to H. The order of subgroup H is the number of elements in H.

A proper subgroup of a group G is a subgroup which is not identical to G. A non-trivial subgroup of G is (usually) any proper subgroup of G which contains an element other than e.

Theorem 2.1: If H is a subgroup of ⟨G,*⟩, then the identity eH in H is identical to the identity e in (G,*).

Proof. If h is in H, then h*eH = h; since h must also be in G, h*e = h; so by theorem 1.4, eH = e.

Theorem 2.2: If H is a subgroup of G, and h is an element of H, then the inverse of h in H is identical to the inverse of h in G.

Proof. Let h and k be elements of H, such that h*k = e; since h must also be in G, h*h -1 = e; so by theorem 1.5, k = h -1.

Given a subset S of G, we often want to determine whether or not S is also a subgroup of G. A handy theorem valid for both infinite and finite groups is:

Theorem 2.3: If S is a non-empty subset of G, then S is a subgroup of G if and only if for all a,b in S, a*b -1 is in S.

Proof. If for all a, b in S, a*b -1 is in S, then

- e is in S, since a*a -1 = e is in S.

- for all a in S, e*a -1 = a -1 is in S

- for all a, b in S, a*b = a*(b -1) -1 is in S

Thus, the axioms of closure, identity, and inverses are satisfied, and associativity is inherited; so S is subgroup.

Conversely, if S is a subgroup of G, then it obeys the axioms of a group.

- As noted above, the identity in S is identical to the identity e in G.

- By A4, for all b in S, b -1 is in S

- By A1, a*b -1 is in S.

The intersection of two or more subgroups is again a subgroup.

Theorem 2.4: The intersection of any non-empty set of subgroups of a group G is a subgroup.

Proof. Let {Hi} be a set of subgroups of G, and let K = ∩{Hi}. e is a member of every Hi by theorem 2.1; so K is not empty. If h and k are elements of K, then for all i,

- h and k are in Hi.

- By the previous theorem, h*k -1 is in Hi

- Therefore, h*k -1 is in ∩{Hi}.

Therefore for all h, k in K, h*k -1 is in K. Then by the previous theorem, K=∩{Hi} is a subgroup of G; and in fact K is a subgroup of each Hi.

Given a group ⟨G,*⟩, define x*x as x², x*x*x*...*x (n times) as xn, and define x0 = e. Similarly, let x -n for (x -1)n. Then we have:

Theorem 2.5: Let a be an element of a group (G,*). Then the set {an: n is an integer} is a subgroup of G.

Proof. A subgroup of this type is called a cyclic subgroup; the subgroup of the powers of a is often written as <a>, and we say that a generates <a>.

Cosets

If S and T are subsets of G, and a is an element of G, we write "a*S" to refer to the subset of G made up of all elements of the form a*s, where s is an element of S; similarly, we write "S*a" to indicate the set of elements of the form s*a. We write S*T for the subset of G made up of elements of the form s*t, where s is an element of S and t is an element of T.

If H is a subgroup of G, then a left coset of H is a set of the form a*H, for some a in G. A right coset is a subset of the form H*a.

If H is a subgroup of G, the following useful theorems, stated without proof, hold for all cosets:

- And x and y are elements of G, then either x*H = y*H, or x*H and y*H have empty intersection.

- Every left (right) coset of H in G contains the same number of elements.

- G is the disjoint union of the left (right) cosets of H.

- Then the number of distinct left cosets of H equals the number of distinct right cosets of H.

Define the index of a subgroup H of a group G (written "[G:H]") to be the number of distinct left cosets of H in G.

From these theorems, we can deduce the important Lagrange's theorem, relating the order of a subgroup to the order of a group:

- Lagrange's theorem: If H is a subgroup of G, then |G| = |H|*[G:H].

For finite groups, this can be restated as:

- Lagrange's theorem: If H is a subgroup of a finite group G, then the order of H divides the order of G.

- If the order of group G is a prime number, G is cyclic.