History of Greenland

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: History

The history of Greenland, the world's largest island, is the history of life under extreme Arctic conditions: an ice cap covers about 95 percent of the island, largely restricting human activity to the coasts.

The first humans are thought to have arrived around 2500 BC. This group apparently died out and were succeeded by several other groups migrating from continental North America. To Europeans, Greenland was unknown until the 10th century, when Icelandic Vikings settled on the southwestern coast. This part of Greenland was apparently unpopulated at the time when the Vikings arrived; the direct ancestors of the modern Inuit Greenlanders are not thought to have arrived until around 1200 AD from the northwest. The Norse settlements along the southwestern coast eventually disappeared after about 500 years. The Inuit thrived in the icy world of the Little Ice Age and were the only inhabitants of the island for several centuries. Denmark-Norway nonetheless claimed the territory, and, after centuries of no contact between the Norse Greenlanders and their Scandinavian brethren, it was feared that the Greenlanders had lapsed back into paganism; so a missionary expedition was sent out to reinstate Christianity in 1721. However, since none of the lost Norse Greenlanders were found, Denmark-Norway instead proceeded to baptize the local Inuit Greenlanders and develop trading colonies along the coast as part of its aspirations as a colonial power. Colonial privileges were retained, such as trade monopoly.

During World War II, Greenland became effectively detached, socially and economically, from Denmark and more connected to the United States and Canada. After the war, control was returned to Denmark, and, in 1953, the colonial status was transformed into that of an overseas amt (county). Although Greenland is still a part of the Kingdom of Denmark, it has enjoyed home rule since 1979. In 1985, the island became the only territory to leave the European Union, which it had joined as a part of Denmark in 1973.

Early Palaeo-Eskimo cultures

The prehistory of Greenland is a story of repeated waves of Palaeo-Eskimo immigration from the islands north of the North American mainland. As one of the furthest outposts of these cultures, life was constantly on the edge and cultures have come and then died out during the centuries. Of the period before the Norse exploration of Greenland, archaeology can give only approximate times:

- The Saqqaq culture: 2500–800 BC (southern Greenland).

- The Independence I culture: 2400–1300 BC (northern Greenland).

- The Independence II culture: 800–1 BC (far northern Greenland).

- The Early Dorset or Dorset I culture: 700 BC–AD 200 (southern Greenland).

There is general consensus that, after the collapse of the Early Dorset culture, the island remained unpopulated for several centuries.

Norse settlement

Islands off Greenland were sighted by Gunnbjörn Ulfsson when he was blown off course while sailing from Norway to Iceland, probably in the early 10th century. During the 980s, explorers from Iceland and Norway arrived at mainland Greenland and, finding the land unpopulated, settled on the southwest coast. The name Greenland (Grænland in Old Norse and modern Icelandic, Grønland in modern Danish and Norwegian) has its roots in this colonization and is attributed to Erik the Red (the Inuit call it Kalaallit Nunaat, meaning "Land of the Kalaallit (Greenlanders)"). There are two written sources on the origin of the name, in The Book of Icelanders ( Íslendingabók), an historical work dealing with early Icelandic history from the 12th century, and in the medieval Icelandic saga, The Saga of Erik the Red (Eiriks saga rauða), which is about the Norse settlement in Greenland and the story of Eric the Red in particular. Both sources write: "He named the land Greenland, saying that people would be eager to go there if it had a good name."

At that time, the inner regions of the long fjords where the settlements were located were very different from today. Excavations show that there were considerable birch woods with birch trees up to 4 to 6 meters high in the area around the inner parts of the Tunuliarfik- and Aniaaq-fjords, the central area of the Eastern settlement, and the hills were grown with grass and willow brushes. This was due to the medieval climate optimum. The Norse soon changed the vegetation by cutting down the trees to use as building material and for heating and by extensive sheep and goat grazing during summer and winter. The climate in Greenland was much warmer during the first centuries of settlement but became increasingly colder in the 14th and 15th centuries with the approaching period of colder weather known as the Little Ice Age.

According to the sagas, Erik the Red was exiled from Iceland for a period of three years, due to a murder. He sailed to Greenland, where he explored the coastline and claimed certain lands as his own. He then returned to Iceland to bring people to settle on Greenland. The date of establishment of the colony is said, in the Icelandic sagas, to have been 985 AD, when 25 ships left with Erik the Red. Only 14 arrived safely in Greenland. This date has been approximately confirmed by radiocarbon dating of some remains at the first settlement at Brattahlid (now Qassiarsuk), which yielded a date of about 1000. According to the sagas, it was also in the year 1000 that Erik's son, Leif Eirikson, left the settlement to discover Vinland, generally assumed to be located in what is now Newfoundland.

This colony existed as two settlement areas — the larger Eastern settlement and the smaller Western settlement Population estimates vary from highs of only 2000 to as many as 10,000 people. More recent estimates such as that of Dr. Niels Lynnerup in "Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga by Fitzhugh Ww and William W. Fitzhugh", have tended toward the lower figure. Ruins of almost 600 farms have been found in the two settlements, 500 in the Eastern settlement and 95 in the Western settlement. This was a significant colony (the population of modern Greenland is only 56,000) and it carried on trade in ivory from walrus tusks with Europe as well as exporting rope, sheep, seals and cattle hides according to one 13th century account. The colony depended on Europe (Iceland and Norway) for iron tools, wood, especially for boatbuilding, which they also may have obtained from coastal Labrador, supplemental foods, and religious and social contacts. Trade ships from Iceland and Norway (from late 13th century all ships were forced by law to sail directly to Norway) traveled to Greenland every year and would sometimes overwinter in Greenland.

In 1126, a diocese was founded at Garðar (now Igaliku). It was subject to the Norwegian archdiocese of Nidaros (now Trondheim); at least five churches in Norse Greenland are known from archeological remains. In 1261, the population accepted the overlordship of the Norwegian King as well, although it continued to have its own law. In 1380 the Norwegian kingdom entered into a personal union with the Kingdom of Denmark. After initially thriving, the Norse settlements declined in the 14th century. The Western Settlement was abandoned around 1350. In 1378, there was no longer a bishop at Garðar. After 1408, when a marriage was recorded, no written records mention the settlers. It is probable that the Eastern Settlement was defunct by the late 15th century although no exact date has been established.

The demise of the Greenland Norse settlements

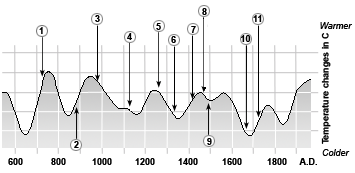

1. From 700 to 750 A.D. people belonging to the Late Dorset Culture move into the area around Smith Sound, Ellesmere Island and Greenland north of Thule.

2. Norse settlement of Iceland starts in the second half of the 9th century.

3. Norse settlement of Greenland starts just before the year 1000.

4. Thule Inuit move into northern Greenland in the 12th century.

5. Late Dorset culture disappears from Greenland in the second half of the 13th century.

6. The Western Settlement disappears in mid 14th century.

7. In 1408 is the Marriage in Hvalsey, the last known written document on the Norse in Greenland.

8. The Eastern Settlement disappears in mid 15th century.

9. John Cabot is the first European in the post-Iceland era to visit Labrador - Newfoundland in 1497.

10. “Little Ice Age” from ca 1600 to mid 18th century. 11. The Norwegian priest, Hans Egede, arrives in Greenland in 1721.

There are many theories as to why the Norse settlements collapsed in Greenland. Jared Diamond, author of Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, suggests that some or all of five factors contributed to the demise of the Greenland colony: cumulative environmental damage, gradual climate change, conflicts with hostile neighbors, the loss of contact and support from Europe, and, perhaps most crucial, cultural conservatism and failure to adapt to an increasingly harsh natural environment. Numerous studies have tested these hypotheses and some have led to significant discoveries. On the other hand there are dissenters: In The Frozen Echo, Kirsten Seaver contests some of the more generally-accepted theories about the demise of the Greenland colony. Thus Seaver asserts that the Greenland colony, towards the end, was healthier than Diamond and others have thought. Seaver believes that the Greenlanders cannot have starved to death. They may rather have been wiped out by Inuit or unrecorded European attacks, or they may have abandoned the colony to return to Iceland or to seek out new homes in Vinland. However, these arguments seem to conflict with the physical evidence from archeological studies of the ancient farm sites. The paucity of personal belongings at these sites is typical of North Atlantic Norse sites that were abandoned in an orderly fashion, with any useful items being deliberately removed but to others it suggests a gradual but devastating impoverishment. Midden heaps at these sites do show an increasingly impoverished diet for humans and livestock.

Greenland was always colder in winter than Iceland and Norway, and its terrain less hospitable to agriculture. Erosion of the soil was a danger from the beginning, one that the Greenland settlements may not have recognized until it was too late. For an extended time, nonetheless, the relatively warm West Greenland current flowing northwards along the southwestern coast of Greenland made it feasible for the Norse to farm much as their relatives did in Iceland or northern Norway. Palynologists' tests on pollen counts and fossilized plants prove that the Greenlanders must have struggled with soil erosion and deforestation. As the unsuitability of the land for agriculture became more and more patent, the Greenlanders resorted first to pastoralism and then to hunting for their food. But they never learned to use the hunting techniques of the Inuit, one being a farming culture, the other living of hunting in more northern areas with pack ice.

To investigate the possibility of climatic cooling, scientists drilled into the Greenland ice caps to obtain core samples. The oxygen isotopes from the ice caps suggested that the Medieval Warm Period had caused a relatively milder climate in Greenland, lasting from roughly 800 to 1200. However from 1300 or so the climate began to cool. By 1420, we know that the "Little Ice Age" had reached intense levels in Greenland. Excavations of midden or garbage heaps from the Viking farms in both Greenland and Iceland show the shift from the bones of cows and pigs to those of sheep and goats. As the winters lengthened, and the springs and summers shortened, there must have been less and less time for Greenlanders to grow hay. By the mid-fourteenth century deposits from a chieftain’s farm showed a large number of cattle and caribou remains, whereas, a poorer farm only several kilometers away had no trace of domestic animal remains, only seal. Bone samples from Greenland Norse cemeteries confirm that the typical Greenlander diet had increased by this time from 20% sea animals to 80%.

Although Greenland seems to have been uninhabited at the time of initial Norse settlement, after a couple of centuries the Norse in Greenland had to deal with the Inuit. The Thule-Inuit were the successors of the Dorset who migrated south and finally came into contact with the Norse in the 12th century. There are limited sources showing the two cultures interacting; however, scholars know that the Norse referred to the Inuit (and Vinland natives) as skraeling. The Icelandic Annals are among the few existing sources that confirm contact between the Norse and the Inuit. They report an instance of hostility initiated by the Inuit against the Norse, leaving eighteen Greenlanders dead and two boys carried into slavery. Archeological evidence seems to show that the Inuit traded with the Norse. On the other hand, the evidence shows many Norse artifacts at Inuit sites throughout Greenland and on the Canadian Arctic islands but very few Inuit artifacts in the Norse settlements. This may indicate either European indifference—an instance of cultural resistance to Inuit crafts among them—or perhaps hostile raiding by the Inuit. It is also quite possible that the Norse were trading for perishable items such as meat and furs and had little interest in other Inuit items, much as later Europeans who traded with Native Americans.

We know that the Norse never learned the Inuit techniques of kayak navigation or ring seal hunting. Indeed, they never learned to adjust to the cold winters as the Inuit did. Archeological evidence plainly establishes that by 1300 or so the Inuit had successfully expanded their winter settlements as close to the Europeans as the outer fjords of the Western Settlement. Yet by 1350, the Norse, for whatever reasons, had completely deserted their Western Settlement. It may also have to do with the Inuit being a hunting society, hunted the Norse livestock, forcing the Norse into conflict or abandonment.

In mild weather conditions, a ship could make the 900-mile (1400 kilometers) trip from Iceland to Eastern settlement within a couple of weeks. Greenlanders had to keep in contact with Iceland and Norway in order to trade. Little is known about any distinctive shipbuilding techniques among the Greenlanders. We do know that they lacked the timber resources of Europe or America, however. So they were completely dependent on Icelandic merchants or, possibly, logging expeditions to the Canadian coast.

The sagas mention Icelanders traveling to Greenland to trade. But the settlement chieftains and large farm owners controlled this trade. The chieftains would trade with the foreign ships and then disperse the goods by trading with the surrounding farmers. Greenlander’s main commodity was the walrus tusk, which was used primarily in Europe as a substitute of elephant ivory for art décor, whose trade had been blocked by conflict with the Islamic world. Professor Gudmundsson also suggests a very valuable narwhale tusk trade, through a smuggling route via western Iceland (where the Greenlanders came from) to the Orkney islands (where Western Icelanders came from).

Many scholars believe that the royal Norwegian monopoly on shipping contributed to the end of trade and contact. However, Christianity and European customs continued to hold sway among the Greenlanders for the greater part of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In 1921, a Danish historian, Paul Norland, found human remains from the Eastern Settlement in the Herjolfsnes church courtyard. The bodies were dressed in fifteenth century medieval clothing with no indications of malnutrition or genetic deterioration. Most had crucifixes around their necks with their arms crossed as in a stance of prayer. Perhaps the buried were sailors having died en route or while over wintering. It is known from Roman papal records that the Greenlanders were excused from paying their tithes in 1345 because the colony was suffering from poverty. The last reported ship to reach Greenland was a private ship that was "blown off course", reaching Greenland in 1406, and departing in 1410 with the last news of Greenland: the burning at the stake of a condemned witch, the insanity and death of the woman this witch was accused of attempting to seduce through witchcraft, and the marriage of the ship's captain, Thorsteinn Ólafsson, to another Icelander, Sigridur Björnsdóttir. However, there are some suggestions of much later unreported voyages from Europe to Greenland, possibly as late as the 1480s.

Another theory holds that contact with Europe brought the Black Death to Greenland Norse’s population. But there is no definite evidence to support this.

The last of the five factors points to the failure of the Norse to adapt to the changing conditions of Greenland. We know that some of the Norse left Greenland in search of a place called Vinland. When hostile natives injured several of them, they returned to Greenland after only 10 years. The Greenland colony survived for some 450-500 years (985 to 1450-1500 AD). The Norse struggled to adapt, as the excavations show plainly. Some of the Norse, perhaps most, dramatically changed their folkways. But it is not known whether they adapted the ways of the Inuit, even, it seems, when faced with extinction. Most likely no single factor brought about their extinction. What is plain is that the settlement died out once and for all, while contributing 5% to the West Greenlander's DNA.

One intriguing fact is that we find very few fish remains among their middens. This has led to much speculation and argument. Most archeologists reject any decisive judgment based on this one fact, however, as fish bones decompose more quickly than other remains, and may have been disposed of in a different manner (recycled?). What seems clear is that the Greenlanders never made a transition to pisciculture. And, given the richness of the surrounding sea as a source of protein, their failure to exploit it as well as the Inuit were able to may have led to their demise Jared Diamond speculates that perhaps an early chieftain suffered food poisoning after eating fish and that his proscription was transmitted from generation to generation up to the end. A large number of fish traps and river fish stations are found widespread through both settlements. However Diamond failed to consult with local farmers in South Greenland, most of whom could have shown him ruins of Norse fish huts and fish traps.

Late Dorset and Thule cultures

The Norse may not have been alone on the island when they arrived; a new influx of Arctic people from the west, the Late Dorset culture, may predate them. However, this culture was limited to the extreme northwest of Greenland, far from the Norse who lived around the southern coasts. Some archaeological evidence may point to this culture slightly predating the Norse settlement. It disappeared around 1300, around the same time as the western of the Norse settlements disappeared. In the region of this culture, there is archaeological evidence of gathering sites for around four to thirty families, living together for a short time during their movement cycle.

Around 1200, another Arctic culture — the Thule — arrived from the west, having emerged 200 years earlier in Alaska. They settled south of the Late Dorset culture and ranged over vast areas of Greenland's west and east coasts. These people, the ancestors of the modern Inuit, were flexible and engaged in hunting of almost all animals on land or in the ocean including big whales. They had dogs which the Dorset did not and used them to pull the dog sledges, they also used bows and arrows contrary to the Dorset. Increasingly settled, they had large food storages to avoid winter famine. The early Thule avoided the highest latitudes, which only became populated again after renewed immigration from Canada in the 19th century.

The nature of the contacts between the Thule, Dorset and Norse cultures are not clear, but may have included trade elements. The level of contact is currently the subject of widespread debate, possibly including Norse trade with Thule or Dorsets in Canada or possible scavenging of abandoned Norse sites (see also Maine penny). No Norse trade goods are known in Dorset archaeological sites in Greenland; the only Norse items found have been characterized as "exotic items." Carved screw threads on tools and carvings with beards found in settlements on the Canadian Arctic islands show contact with the Norse. Some stories tell of armed conflicts between, and kidnappings by, both Inuit and Norse groups. The Inuit may have reduced Norse food sources by displacing them on hunting grounds along the central west coast. These conflicts can be one contributing factor to the disappearance of the Norse culture as well as for the Late Dorset, but few see it as the main reason. Whatever the cause of that mysterious event, the Thule culture handled it better, not becoming extinct.

Colonization and exploration

In 1536, Denmark and Norway were officially merged and most pioneers and housing came from Norway. Greenland came to be seen as a Danish dependency rather than a Norwegian one. Even with the contact broken, the Danish King continued to claim lordship over the island. In the 1660s, this was marked by the inclusion of a polar bear in the Danish coat of arms. In the second half of the 17th century Dutch, German, French, Basque, and Dano-Norwegian ships hunted bowhead whales in the pack ice off the east coast of Greenland, regularly coming to shore to trade and replenish drinking water. Their trade was later forbidden by Danish monopoly merchants.

In 1721 a joint merchant-clerical expedition led by Norwegian missionary Hans Egede was sent to Greenland, not knowing whether the civilization remained there, and worried that if it did, they might still be Catholics 200 years after the Reformation, or, worse yet, have abandoned Christianity altogether. The expedition can also be seen as part of the Danish colonization of the Americas. Gradually, Greenland became opened for Danish merchants, and closed for those from other countries. This new colony was centered at Godthåb ("Good Hope") on the southwest coast. Some of the Inuit that lived close to the trade stations were converted to Christianity. In South Greenland a German missionary post attracted South-East Greenlanders, who subsequently abandoned that part of the coast.

When Norway was separated from Denmark in 1814, after the Napoleonic Wars, the colonies, including Greenland, remained Danish. The 19th century saw increased interest in the region on the part of polar explorers and scientists like William Scoresby and Greenland born Knud Rasmussen. At the same time, the colonial elements of the earlier trade-oriented Danish tight-fist on Greenland expanded. Missionary activities were largely successful under wrath of God. In 1861, the first Greenlandic language journal was founded. Danish law still applied only to the Danish settlers, though.

At the turn of the 19th century, the northern part of Greenland was still sparsely populated; only scattered hunting inhabitants were found there. During that century however, Inuit families immigrated from British North America to settle in these areas. The last group from what later became Canada arrived in 1864. During the same time, the North Eastern part of the coast became depopulated following the violent 1783 Lakagígar eruption in Iceland.

Democratic elections for the district assemblies of Greenland were held for the first time in 1862–1863, although no assembly for the land as a whole was allowed. In 1911, two Landstings were introduced, one for northern Greenland and one for southern Greenland, not to be finally merged until 1951. All this time, most decisions were made in Copenhagen, where the Greenlanders had no representation.

Towards the end of the 19th century, traders criticized the Danish trade monopoly. It was argued that it kept the natives in non-profitable ways of life, holding back the potentially large fishing industry. Many Greenlanders however were satisfied with the status quo, as they felt the monopoly would secure the future of commercial whaling. It probably did not help that the only contact the local population had with the outside world was with Danish settlers. Nonetheless, the Danes gradually moved over their investments to the fishing industry.

At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, American explorers, including Robert Peary, explored the northern sections of Greenland. Peary discovered that Greenland was an island and mapped the northern coasts. These discoveries were considered to be the basis of an American territorial claim in the area. All claims in Greenland itself were ceded to Denmark by a declaration connected with the U.S. Virgin Islands purchase treaty.

Strategic importance

After Norway regained full independence in 1905, it refused to accept Denmark's sovereignty over Greenland, which was a former Norwegian possession severed from Norway proper in 1814. In 1931, Norwegian whaler Hallvard Devold occupied uninhabited eastern Greenland, on his own initiative. After the fact, the occupation was supported by the Norwegian government. Two years later, the Permanent Court of International Justice ruled in favour of the Danish view.

During World War II, when Germany extended its war operations to Greenland, Henrik Kauffmann, the Danish Minister to the United States — who had already refused to recognize the German occupation of Denmark — signed a treaty with the United States on April 9, 1941, granting the US Armed Forces permission to establish stations in Greenland. Because of the difficulties for the Danish government to govern the island during the war, and because of successful export, especially of cryolite, Greenland came to enjoy a rather independent status. Its supplies were guaranteed by the United States and Canada.

During the Cold War, Greenland had a strategic importance, controlling parts of the passage between the Soviet Arctic harbours and the Atlantic, as well as being a good base for observing any use of intercontinental ballistic missiles, typically planned to pass over the Arctic. The United States therefore had a geopolitical interest in Greenland, and in 1946, the United States offered to buy Greenland from Denmark for $100,000,000, but Denmark did not agree to sell. In 1951, the Kauffman treaty was replaced by another one. The Thule Air Base at Thule (now Qaanaaq) in the northwest was made a permanent air force base. In 1953, some Inuit families were forced by Denmark to move from their homes to provide space for extension of the base. For this reason, the base has been a source of friction between the Danish government and the Greenlandic people. Tensions mounted when, on January 21, 1968, there was a nuclear accident — a B-52 Stratofortress carrying four hydrogen bombs crashed near the base, leaking large amounts of plutonium over the ice. Although most of the plutonium was retrieved, natives still make claims about resulting deformations in animals.

Home rule

The colonial status of Greenland was lifted in 1953, when it became an integral part of the Danish kingdom, with representation in the Folketing. Denmark also began a programme of providing medical service and education to the Greenlanders. As a result, the population became more and more concentrated to the towns. Since most of the inhabitants were fishermen and had a hard time finding work in the towns, these population movements may have contributed to unemployment and other social problems that have troubled Greenland lately.

As Denmark engaged in the European cooperation later to become the European Union, friction with the former colony grew. Greenlanders felt the European customs union would be harmful to their trade, which was largely carried out with non-European countries such as the United States and Canada. After Denmark, including Greenland, joined the union in 1973 (despite 70.3% of Greenlanders having voted against entry in the referendum), many residents thought that representation in Copenhagen was not sufficient, and local parties began pleading for self-government. The Folketing granted this in 1978, the home rule law coming into effect the following year. On February 23, 1982, a majority (53%) of Greenland's population voted to leave the European Community, which it did in 1985, the only governmental entity to have done so.

Self-governing Greenland has portrayed itself as an Inuit nation. Danish placenames have been replaced. The centre of the Danish civilization on the island, Godthåb, has become Nuuk, the capital of a close-to-sovereign country. In 1985, a Greenlandic flag was established, using the colours of the Danish Dannebrog. However, the movement for complete sovereignty is still weak.

International relations, a field earlier handled by Denmark, are now left largely, but not entirely, to the discretion of the home rule government. After leaving the EU, Greenland has signed a special treaty with the Union, as well as entering several smaller organizations, not least with Iceland and the Faroe Islands, and with the Inuit populations of Canada and Russia. It was also one of the founders of the environmental Arctic Council cooperation in 1996. Renegotiation of the 1951 treaty between Denmark and the United States, with a direct participation of self-governing Greenland, is an issue, and the 1999–2003 Commission on Self-Governance suggested that Greenland should then aim at the Thule Air Base eventually becoming an international surveillance and satellite tracking station, subject to the United Nations.

Modern technology has made Greenland more accessible, not least due to the breakthrough of aviation. However, the capital Nuuk still lacks an international airport (see transportation in Greenland). Television broadcasts began in 1982.