King Arthur

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Ancient History, Classical History and Mythology; British History 1500 and before (including Roman Britain)

King Arthur is a fabled British leader and a prominent figure in Britain's legendary history, said in many medieval tales and chronicles to have taken the mantle of rulership over Britain and defended his land against Saxon invaders following the withdrawal of Rome. Arthur's story includes considerable elements of legend and folklore, and his very existence is debated and has become a point of fierce controversy among modern historians. The scarce historical background to Arthur is found scattered across various works including those of " Nennius" and Gildas and in the Annales Cambriae. The legendary Arthur was developed as a figure of international interest largely through the 12th century pseudo-history of Geoffrey of Monmouth, although Welsh and Breton stories and poems were circulating before he wrote.

Chrétien de Troyes began the literary tradition of Arthurian romance, which subsequently became one of the principal themes of medieval literature. Medieval Arthurian writing reached its conclusion in Thomas Mallory's comprehensive Morte D'Arthur, published in 1485. Modern interest in Arthur was revived by Alfred Lord Tennyson in Idylls of the King, and in the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites. Key modern reworkings of the Arthurian legends include Richard Wagner's opera Parsifal, Mark Twain's satiric A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, and T. H. White's The Once and Future King. Despite the controversy over the existence of a single historical Arthur, he was recently ranked as one of the 100 Greatest Britons of all time.

The central themes of the Arthurian cycle vary depending on which texts are examined. However, they include the establishment of Arthur as king through the sword in the stone episode, the advice of the wizard Merlin, the establishment of the fellowship of knights known as the Round Table and its associated code of chivalry, the defence of Britain against the Saxons, numerous magical adventures associated with particular knights – notably Kay, Gawain, Lancelot, Percival and Galahad – the enmity of Arthur's half-sister Morgan le Fay, the quest for the Holy Grail, the adultery of Lancelot and Queen Guinevere, the final battle with Mordred, and the legend of Arthur's future return. The magical sword Excalibur, the castle Camelot and the Lady of the Lake also play pivotal roles.

Historicity

The historicity of the King Arthur legend has long been debated by scholars. One school of thought, based on references in the Historia Brittonum and Annales Cambriae, would see Arthur as a shadowy historical figure, a Romano-British leader fighting against the invading Anglo-Saxons sometime in the late 5th to early 6th century. The Historia Brittonum ("History of the Britons"), a 9th century Latin historical compilation attributed in some late manuscripts to a Welsh cleric called Nennius, gives a list of twelve battles fought by Arthur, culminating in the Battle of Mons Badonicus, where he is said to have single-handedly killed 960 men. However, recent studies suggest that the Historia Brittonum cannot be considered a reliable source for the history of this period. The other text that is usually used by this school of thought is the 10th century Annales Cambriae ("Welsh Annals"), which also links Arthur with the Badon. The Annales dates this battle to 516–518, and also mentions the Battle of Camlann, in which Arthur and Medraut were both killed, dated to 537–539. This has often been used to bolster confidence in the Historia's account and confirm that Arthur really did fight this battle. Problems have, though, been identified with using this source to support the account of Historia Brittonum. The latest research into the Annales Cambriae shows that this chronicle was based around one which was started in the late 8th century in Wales, around 300 years after Arthur would have lived. Additionally, because of the complex textual history of the Annales Cambriae there can be no certainty that the Arthurian annals were put into it even that early. As a result, it is more likely that they entered it at some point in the 10th century and that they had no existence in any earlier set of annals, with the Badon entry probably being derived from the Historia Brittonum.

This lack of convincing early evidence is the reason that many modern historians prefer to avoid including Arthur in their accounts of post-Roman Britain. Thomas Charles-Edwards commented that "at this stage of the enquiry, one can only say that there may well have been an historical Arthur [but]… the historian can as yet say nothing of value about him", and this is one of the more positive assessments. Indeed, it is not certain that Arthur was even considered a king in these texts: neither the Historia or the Annales call him this, with the former calling him instead dux bellorum or " dux (leader) of battles". These modern admissions of ignorance are a relatively recent trend; earlier generations of historians were less sceptical. Historian John Morris went so far as to make the putative reign of Arthur at the turn of the 5th century the organising principle of his history of sub-Roman Britain and Ireland, The Age of Arthur (1973). Even so, he found little to say of an historic Arthur, save as an example of the idea of kingship, one among such contemporaries as Vortigern, Cunedda, Hengest and Coel. Morris argues that Arthur's power base would have been in the Celtic areas of Wales, Cornwall and the West Country, or the Brythonic " Old North" which covered modern Northern England and southern Scotland.

Partly in reaction to such theories as this, another school of thought emerged which argued that Arthur had no historical existence at all. Morris's Age of Arthur prompted Nowell Myres to write "no figure on the borderline of history and mythology has wasted more of the historian's time". In support of this it is often noted that Gildas' 6th century polemic De Excidio Britanniae ("On the Ruin of Britain"), written within living memory of the Battle of Mons Badonicus, mentions that battle but does not mention Arthur. Similarly, Arthur is entirely absent from Bede's early 8th century Ecclesiastical History of the English People, another major early source for post-Roman history which mentions Badon. As David Dumville has written, in perhaps the most famous scholarly quotation on the "historical Arthur", "I think we can dispose of him [Arthur] quite briefly. He owes his place in our history books to a ‘no smoke without fire’ school of thought... The fact of the matter is that there is no historical evidence about Arthur; we must reject him from our histories and, above all, from the titles of our books." Indeed, some academics argue that Arthur was originally a fictional hero of folklore – or even a half-forgotten Celtic deity – who became credited with real deeds in the distant past, citing parallels with the supposed change of the sea-god Lir into King Lear, the Kentish totemic horse-gods Hengest and Horsa, who were historicised by the time of Bede's account and given an important role in the 5th century Anglo-Saxon conquest of eastern Britain, the founder-figure of Caer-fyrddin, Merlin (Welsh Myrddin), or the Norse demigod Sigurd or Siegfried, who was historicised in the Nibelungenlied by associating him with a famous historical 5th-century battle between Huns and the Burgundians.

Fundamentally, historical documents for the post-Roman period are scarce, so a definitive final answer to this question is unlikely. Sites and places have been identified as "Arthurian" since the 12th century, but archaeology can confidently reveal names only through inscriptions found in secure contexts. The so-called " Arthur stone" discovered in 1998 in securely dated 6th century contexts among the ruins at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, a secular, high status settlement of Sub-Roman Britain, created a brief stir but proved irrelevant, and there is no other inscriptional evidence for Arthur which has not been tainted with the suggestion of forgery. Although several identifiable historical figures have been suggested as the historical basis for Arthur, ranging from Lucius Artorius Castus, a Roman officer who served in Britain in the 2nd century; Roman usurper emperors like Magnus Maximus; and sub-Roman British rulers like Riotamus, Ambrosius Aurelianus, Owain Ddantgwyn and Athrwys ap Meurig, there is as yet no way of proving these cases to the satisfaction of the sceptics.

Name

The origin of the name Arthur remains a matter of debate. Some suggest it is derived from the Latin family name Artorius, of obscure and contested etymology. Others propose a derivation from Welsh arth (earlier art), meaning "bear", suggesting art-ur, "bear-man", (earlier *Arto-uiros) is the original form, although there are difficulties with this theory. It may be relevant to this debate that Arthur's name appears as Arthur, or Arturus, in early Latin Arthurian texts, never as Artorius. However, this may not say anything about the origin of the name Arthur, as Artorius would regularly become Art(h)ur when borrowed into Welsh; all it would mean is that the surviving Latin references to a historical Arthur (if he was called Artorius and really existed) must certainly date from after the 6th century, as John Koch has pointed out. An alternate theory links the name Arthur to Arcturus, the brightest star in the constellation Boötes, near Ursa Major or the Great Bear. Classical Latin Arcturus would also have become Art(h)ur when borrowed into Welsh, and its brightness and position in the sky led people to regard it as the "guardian of the bear" and the "leader" of the other stars in Boötes. The exact significance of such etymologies as these is unclear. It is often assumed that an Artorius derivation would mean that the legends of Arthur had a genuine historical core, but recent studies suggests this assumption may not be well founded. In contrast, a derivation of Arthur from Arcturus might be taken to indicate a non-historical origin for Arthur, but Toby Griffen has in fact suggested it was an alternate name for a historical Arthur designed to appeal to Latin-speakers. Related to this suggestion is one popular theory that, whatever the origins of the name Arthur, it was not actually a name but rather a nom de guerre or an epithet borne by the man who led the Britons against the Saxons. Some Arthurian enthusiasts suggest that the nom de guerre Arthur is in fact a combination of the Welsh and Latin words for "bear", art and ursus. However, such ideas have not, as yet, gained widespread acceptance.

Medieval literary traditions

The creator of the familiar literary persona of Arthur was Geoffrey of Monmouth, with his pseudohistorical Historia Regum Britanniae ("History of the Kings of Britain"), written in the 1130s. The textual sources for Arthur are usually divided into those that were written before Geoffrey's Historia was published (known as 'pre-Galfridian' texts, from the Latin form of Geoffrey, Galfridus) and those that followed this, and could not avoid his influence (Galfridian, or post-Galfridian, texts).

Pre-Galfridian traditions

The earliest literary references to Arthur come from Welsh and Breton sources. There have been few attempts to define the nature and character of Arthur in the pre-Galfridian tradition as a whole, rather than in a single text or text/story-type. One recent academic survey that does attempt this, by Thomas Green, identifies three key strands to the portrayal of Arthur in this earliest material. The first is that he was a peerless warrior who functioned as the monster-hunting Protector of Britain from all internal and external threats. Some of these are human threats, such as the Saxons he fights in the Historia Brittonum, but the majority are supernatural, including were-wolves, giant cat-monsters, destructive divine boars, dragons, giants and witches. The second is that the pre-Galfridian Arthur was a figure of folklore (particularly topographic or onomastic folklore) and localized magical wonder-tales, the leader of a band of superhuman heroes who live in the wilds of the landscape. The third and final strand is that the early Welsh Arthur had a close connection with the Welsh Otherworld, Annwn. On the one hand, he frees prisoners from Otherworldly fortresses and launches assaults on the same for magical treasures. On the other, his warband in the earliest sources includes former pagan gods and his wife and possessions are clearly Otherworldly in origin.

One of the most famous Welsh poetic references to Arthur comes in the Welsh collection of heroic death-songs known as Y Gododdin ("The Gododdin"), attributed to the 6th-century poet Aneirin. In one stanza, the bravery of a warrior who slew 300 enemies is praised, but it is then noted that despite this "he was no Arthur", that is to say his feats cannot compare to the valour of Arthur. Y Gododdin is known only from a manuscript of the 13th century, so it is impossible to determine whether this passage is original or a later interpolation: it is often argued to go back to the 9th or 10th century, but John Koch's notion that it belongs to a 7th century or earlier version of Y Gododdin is generally held to be still unproven. Several poems attributed to Taliesin, a poet said to have lived in the 6th century, also refer to Arthur, although these all probably date from between the 8th and 12th centuries. They include Kadeir Teyrnon ("The Chair of the Prince"), which refers to "Arthur the Blessed", Preiddeu Annwn ("The Spoils of the Annwn"), which recounts an expedition of Arthur to the Otherworld, and Marwnat vthyr pen[dragon] ("The Elegy of Uthyr Pen[dragon]"), which refers to Arthur's valour and is suggestive of a father-son relationship for Arthur and Uthyr that pre-dates Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Other early Welsh Arthurian texts include a poem found in the Black Book of Carmarthen, Pa gur yv y porthaur? ("What man is the gatekeeper?"). This takes the form of a dialogue between Arthur and the gatekeeper of a fortress he wishes to enter, in which Arthur recounts the names and deeds of himself and his men, notably Cei and Bedwyr. The Welsh prose tale Culhwch and Olwen (c.1100), included in the modern Mabinogion collection, has a much longer list of more than 200 of Arthur's men, though Cei and Bedwyr again take a central place. The story as a whole tells of Arthur helping his kinsman Culhwch win the hand of Olwen, daughter of Ysbaddaden Chief-Giant, by completing a series of apparently impossible tasks, including the hunt for the great semi-divine boar Twrch Trwyth. This latter tale is also referenced in the 9th century Historia Brittonum, with the boar there named Troy(n)t. Finally, Arthur is referenced numerous times in the Welsh Triads, a collection of short summaries of Welsh tradition and legend which are classified into groups of three linked characters or episodes in order to assist recall. The later manuscripts of the Triads are partly derivative from Geoffrey of Monmouth and later Continental traditions, but the earliest ones show no such influence and are usually agreed to refer to pre-existing Welsh traditions. Even in these, however, Arthur's court has started to embody legendary Britain as a whole, with "Arthur's Court" being sometimes substituted for "The Island of Britain" in the formula "Three XXX of the Island of Britain". While it is not clear from the Historia Brittonum and the Annales Cambriae that Arthur was even considered a king, by the time Culhwch and Olwen and the Triads were written he had become Penteyrnedd yr Ynys hon, "Chief of the Lords of this Island", the overlord of Wales, Cornwall and the North.

In addition to the pre-Galfridian Welsh poems and tales, Arthur appears in some other early Latin texts. In particular, Arthur appears in a number of well known vitae ("Lives") of post-Roman saints, none of which are now generally considered to be reliable historical sources (the earliest probably dates from the 11th century). According to the Life of Saint Gildas, written in the early 12th century by Caradoc of Llancarfan, Arthur is said to have killed Gildas' brother Hueil and to have rescued his wife Gwenhwyfar from Glastonbury in an euhemerized Otherworldly tale. In the Life of Saint Cadoc, written around 1100 or a little before by Lifris of Llancarfan, the saint gives protection to a man who killed three of Arthur's soldiers, and Arthur demands a herd of cattle as wergeld for his men. Cadoc delivers them as demanded, but when Arthur takes possession of the animals, they transform into bundles of ferns. Similar incidents are described in the probably 12th or 12th century medieval biographies of Carannog, Padarn, and Eufflam. A less obviously legendary account appears in the Legenda Sancti Goeznovii, which is often claimed to date from the early 11th century although the earliest manuscript of this text dates from the 15th century.

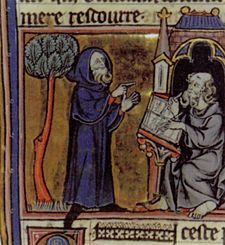

Geoffrey of Monmouth

The first narrative account of Arthur's life is found in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Latin work Historia Regum Britanniae ("History of the Kings of Britain"). This work, completed c. 1138, represents an imaginative and fanciful account of British kings from the legendary Trojan exile Brutus to the 7th century Welsh prince Cadwallader. Geoffrey places Arthur in the same post-Roman period as the Historia Brittonum and Annales Cambriae do. He introduces Arthur's father, Uther Pendragon, and his magician advisor Merlin, and the story of Arthur's conception, in which Uther, disguised as his enemy Gorlois by Merlin's magic, fathers Arthur on Gorlois' wife Igerna at Tintagel. On Uther's death, the fifteen-year-old Arthur succeeds him as King of Britain and fights a series of battles, similar to those in the Historia Brittonum, culminating in the Battle of Bath. He then defeats the Picts and Scots, before creating an Arthurian empire through his conquests of Ireland, Iceland, and the Orkney Islands. After twelve years of peace, Arthur sets out to expand his empire once more, taking control of Norway, Denmark and Gaul. The latter country is still held by the Roman Empire when it is conquered and Arthur's victory naturally leads to a further confrontation between his empire and that of Rome. Arthur and his warriors, including Kaius (Kay), Beduerus (Bedivere) and Gualguanus (Gawain), defeat the Roman emperor Lucius Tiberius in Gaul but, as he prepares to march on Rome, Arthur hears news that his nephew Modredus – whom he had left in charge of Britain – has married his wife Guenhuuara and seized the throne. Arthur returns to Britain and defeats and kills Modredus on the river Camblam in Cornwall, but he is mortally wounded. He hands the crown to his kinsman Constantine and is taken to the isle of Avalon to be healed of his wounds, never to be seen again.

How much of this narrative and life-story was Geoffrey's own invention is open to debate. Certainly Geoffrey seems to have made use of the list of Arthur's twelve battles against the Saxons found in the 9th century Historia Brittonum. Arthur's personal status as the king of all Britain would also seem to be borrowed from pre-Galfridian tradition, being found in Culhwch and Olwen, the Triads and the Saints' Lives. Finally, Geoffrey borrowed many of the names for Arthur's possessions and companions from the pre-Galfridian Welsh tradition, including Kaius (Cei), Beduerus (Bedwyr), Guenhuuara (Gwenhwyfar) and Uther (Uthyr). However, whilst names and titles may have been borrowed, Brynley Roberts has argued that "the Arthurian section is Geoffrey’s literary creation and it owes nothing to prior narrative." So, for instance, the Welsh Medraut is made the villainous Modredus by Geoffrey, but there is no trace of such a negative character for this figure in Welsh sources until the 16th century. There have been relatively few modern attempts to challenge this notion that the Historia Regum Britanniae is primarily Geoffrey's own work, with scholarly opinion often seeming to echo William of Newburgh's late 12th century comment that Geoffrey "made up" his narrative, perhaps through an "inordinate love of lying". Geoffrey Ashe is one dissenter from this view, believing that Geoffrey's narrative is partially derived from a lost source telling of the deeds of a 5th century British king named Riotamus, this figure being the original Arthur, although historians and Celticists have been reluctant to follow Ashe in his conclusions.

Whatever his sources may have been, the incredible popularity of Geoffrey's Historia Regum Britanniae cannot be denied. Well over 200 manuscript copies of Geoffrey’s Latin work are known to have survived, and this does not include translations into other languages. Thus, for example, around sixty manuscripts are extant containing Welsh-language versions of the Historia, the earliest of which were created in the 13th century; the old notion that some of these Welsh versions actually underlie Geoffrey's Historia, put forward by antiquarians such as the 18th-century Lewis Morris, has long since been discounted in academic circles and results from a "combination of misunderstanding and wishful thinking", to quote P. C. Bartrum. As a result of this popularity, Geoffrey's Historia Regum Britanniae was enormously influential on the later medieval development of the Arthurian legend. Whilst it was by no means the only creative force behind Arthurian romance, many elements of it were borrowed and developed (e.g. the death of Arthur) and it provided the historical framework into which the romancers' tales of magical and wonderful adventures were inserted.

Romance traditions

The popularity of Geoffrey's Historia and its derivative works (such as Wace's Roman de Brut) is generally agreed to be one important factor in explaining the appearance of significant numbers of new Arthurian works in 12th and 13th century continental Europe, particularly in France. This is not, however, to say that it was the only Arthurian influence on the developing " Matter of Britain". There is clear evidence for a knowledge of Arthur and Arthurian tales on the Continent before Geoffrey's work became widely known (see for example, the Modena Archivolt), as well as for the use of 'Celtic' names and stories not found in Geoffrey's Historia in the Arthurian romances. From the perspective of Arthur, perhaps the most significant effect of this great outpouring of new Arthurian story was on the role of the king himself: much of this 12th century and later Arthurian literature "is only marginally, if at all, about Arthur... [the] emphasis shifts quickly to Lancelot and Guenevere, to Perceval, Galahad, or Gawain, to Tristan and Isolde." Whereas Arthur is very much at the centre of the pre-Galfridian material and Geoffrey's Historia itself, in the romances he is rapidly sidelined. Furthermore, his character also alters significantly. In both the earliest materials and Geoffrey he is a great and ferocious warrior, who laughs as he personally slaughters witches and giants and takes a leading role in all military campaigns, whereas in the continental romances he becomes the roi fainéant, the "do-nothing king", whose "inactivity and acquiescence constituted a central flaw in his otherwise ideal society." Arthur's main function in these works is frequently to play the role of a wise, dignified, even-tempered and somewhat bland monarch, and even on occasion a feeble one too. So, he simply turns pale and silent when he learns of Lancelot's affair with Guinevere in the Mort Artu, whilst in Chrétien's Yvain he is unable to stay awake after a feast and has to retire for a nap. Nonetheless, as Norris Lacy has observed, whatever his faults and frailties may be in these Arthurian romances, "his prestige is never -- or almost never -- compromised by his personal weaknesses... his authority and glory remain intact."

Arthur and his retinue appear in some of the Lais of Marie de France, but it was the work of another French poet, Chrétien de Troyes, that had the greatest influence on the development of Arthur and his legend. Chrétien wrote five Arthurian romances between c.1170 and c.1190. Erec and Enide and Cligès are tales of courtly love with Arthur's court as their backdrop, and Yvain, the Knight of the Lion features Yvain and Gawain in a supernatural adventure. However, the most significant for the development of the Arthurian legend are Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart, which introduces Lancelot and his adulterous relationship with Arthur's queen ( Guinevere), and Perceval, the Story of the Grail, which introduces the Holy Grail and the Fisher King. Chrétien de Troyes was thus "instrumental both in the elaboration of the Arthurian legend and in the establishment of the ideal form for the diffusion of that legend", and much of what came after built upon the foundations he had laid. So, Perceval, although unfinished, was particularly popular; four separate continuations of the poem appeared over the next half century, with the notion of the Grail and its quest being developed by other writers such as Robert de Boron. Similarly, Lancelot and his affair with Guinevere became one of the classic motifs of the Arthurian legend, although the Lancelot of the Prose Lancelot (c.1225) and later texts was a combination of Chrétien's character and that of Ulrich von Zatzikhoven's Lanzelet. Chrétien's work even appears to feed back into Welsh Arthurian literature, where there are found three Arthurian romances which are closely similar to those of Chrétien, albeit with some significant differences: Owain, or the Lady of the Fountain is related to Chrétien's Yvain, Geraint and Enid to Erec and Enide, and Peredur son of Efrawg to Perceval. However, it is not entirely certain that these Welsh romances are derivative of Chrétien's works. A number of academics, including Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan, certainly consider this to be the case, but others maintain that the relationship could move in the opposite direction or that there is a lost common source for both versions.

Up to c.1210, continental Arthurian romance was expressed primarily through poetry; after this date the tales began to be told in prose. The most significant of these 13th century prose romances was the Vulgate Cycle, (also known as the Lancelot-Grail Cycle), a series of five Middle French prose works written in the first half of that century. These five works were the Estoire del Saint Grail, the Estoire de Merlin, the Lancelot propre (or Prose Lancelot, which made up half the entire Vulgate Cycle on its own), the Queste del Saint Graal and the Mort Artu. They combine to form the first coherent version of the entire Arthurian legend. The Cycle introduced the character of Galahad, expanded the role of Merlin, and established the role of Camelot, first mentioned in passing in Chrétien's Lancelot, as Arthur's primary court. This series of texts was quickly followed by the Post-Vulgate Cycle (c.1230-40), of which the Suite du Merlin is a part, which greatly reduced the importance of Lancelot's affair with Guinevere, focussing more on the Grail quest. Nonetheless, Arthur remained a relatively minor character in these French prose romances (in the Vulgate itself he only figures significantly in the Estoire de Merlin and the Mort Artu).

The development of the medieval Arthurian cycle culminated in Le Morte d'Arthur, Thomas Malory's retelling of the entire legend in a single work in English in the late 15th century. Malory based his book -- originally titled The Whole Book of King Arthur and of His Noble Knights of the Round Table -- on the various previous romance versions, in particular the Vulgate Cycle, and appears to have aimed at creating a comprehensive and authoritative collection of Arthurian stories. Perhaps as a result of this and the fact that Le Morte D'Arthur was one of the earliest printed books in England, published by William Caxton in 1485, most later Arthurian works are derivative of Malory's.

Decline, revival and the modern legend

Post-medieval literature

The end of the Middle Ages brought with it a waning of interest in King Arthur. Although Malory's English version of the great French romances was popular, there were increasing attacks upon the truthfulness of the historical framework of the Arthurian romances -- established since Geoffrey of Monmouth's time -- and thus the legitimacy of the whole Matter of Britain. So, for example, the 16th century humanist scholar Polydore Vergil famously rejected the idea of a post-Roman Arthurian empire as a fabrication, to the horror of Welsh and English antiquarians. Social changes associated with the end of the medieval period and the renaissance also conspired to rob the Arthurian legend of some of its power to enthrall contemporary audiences, with the result that 1634 saw the last printing of Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur for nearly 200 years. This is not to say that King Arthur and the Arthurian legend were entirely abandoned until the early 19th century, but the material was certainly taken less seriously and often used simply as vehicle for allegories of 17th and 18th century politics. Thus Richard Blackmore's epics Prince Arthur (1695) and King Arthur (1697) feature Arthur as an allegory for the struggles of William III against James II. Similarly, the most popular Arthurian tale throughout this period seems to have been that of Tom Thumb, which was set in Arthurian Britain and was told first through chapbooks and later through the political plays of Henry Fielding.

Tennyson and the revival

The revival of interest in King Arthur and the Arthurian legend of the medieval romances began in the early 19th century. Partly this revival was motivated by a new respect for medieval chivalrous values as models for 19th century gentlemen, and in part it was a feature of the linked phenomena of medievalism, Romanticism and the Gothic Revival. The first major evidence for this renewed interest comes in 1816, when Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur came back into print for the first time since 1634. Initially the medieval Arthurian legend seems to have been of particular interest to poets, with William Wordsworth being inspired by it to write "The Egyptian Maid" (1835), an allegory of the Holy Grail. Pre-eminent amongst these poets was Alfred Lord Tennyson, whose first Arthurian work (" The Lady of Shalott") was published in 1832 and was based on a medieval Italian novelette, Donna di Scalotta. This and his subsequent Arthurian poems, such as "Sir Launcelot and Queen Guinevere" and the "Morte d'Arthur", aroused considerable public interest in the legend of Arthur and brought Malory’s tales (on which they were based) to a new, wider audience.

Tennyson's Arthurian work reached its peak of popularity with his Idylls of the King. This was first published in 1859, when it sold 10,000 copies within its first week, and was expanded several times from then on until 1889. In the Idylls Tennyson covered and reworked the whole romance narrative of Arthur's career from birth to death, with Arthur now a symbol of ideal manhood — rather than the simply national hero or roi fainéant of the medieval tradition — whose attempt to establish an ideal kingdom on earth fails, finally, through human weakness. The influence of Tennyson on the Arthurian revival can be observed in a number of ways. One way is simply to look to Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur once more, on which much of Tennyson's work was based. The first modernization of Malory into contemporary English was published shortly after Idylls of the King appeared, in 1862, with this seeing 6 further editions and 5 competitors before the century ended. Another is to look to great explosion of Arthurian poetry and art in the second half of the 19th century. William Morris, Matthew Arnold and Algernon Charles Swinburne were all inspired to write Arthurian verse by Tennyson's Idylls (partly through disapproval of Tennyson's Arthurian poetry, it must be noted). So too were the artists of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, who were initially inspired by Tennyson and from whom they graduated to Malory and the medieval tradition. A final way is to consider that humourous fairy-story, the tale of Tom Thumb, which was the main manifestation of the Arthurian legend in the 18th century. Whilst Tom maintains his small stature and comic potential, his stories are rewritten after the publication of Tennyson's verse to include ever more elements from the medieval Arthurian romances, both in terms of events and ethos.

This interest in the 'Arthur of romance' continued through the 19th century and into the 20th century, and it was not confined to England alone. So, for example, Richard Wagner was inspired by the romance tradition to produce his operas Tristan und Isolde and Parsifal, his music in turn then influencing the English Pre-Raphaelites such as Burne-Jones. The revived Arthurian romance also proved influential in America, with such books as Sidney Lanier's The Boy's King Arthur (1880) reaching wide audiences and providing inspiration for Mark Twain's satiric A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889). The Arthurian revival did not, however, continue unabated in all areas. By the end of the 19th century interest in it amongst artists was merely vestigial, confined mainly to Pre-Raphaelite imitators. Furthermore, the romance tradition of Arthur could not avoid being affected by the First World War, which damaged the public ethos of chivalry and thus interest in the medieval manifestations of this. It did, however, remain sufficiently powerful to persuade Thomas Hardy, Laurence Binyon and John Masefield to compose Arthurian plays and it served as the inspiration for T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land.

The modern legend

In the latter half of the 20th century the influence of the romance tradition continued to make itself felt, through novels such as T. H. White's The Once and Future King (1958, based on Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur) and Marion Zimmer Bradley's The Mists of Avalon (1981), and comic-strips such as Prince Valiant (1937-present). Just as Tennyson reworked his romance materials to suit his day and desired message, so too is it often the case with these modern treatments, for example Bradley's tale takes a determinably feminist approach to the legend and focussing on religious struggles between paganism and Christianity. All three of the above literary works have been made into films and/or TV series — in 1965 by Disney; 1953 by Twentieth Century-Fox; and 2001 by Turner Network Television, respectively — and the Arthurian romances have continued to dominate this medium. So, for example, the musical Camelot, with its focus on the love between Lancelot and Guinevere, was made into a film in 1967, whilst films including Tristan et Iseult (1972), Gawain and the Green Knight (1973), Tristan and Isolt (1979), Sword of the Valiant (1983), The Fisher King (1991), First Knight (1995) and Merlin (1998) are all derivative of the romances. This debt is particularly evident and (according to critics) successfully handled in Robert Bresson's Lancelot du Lac (1974, based on the Vulgate Mort Artu), Eric Rohmer's Perceval le Gallois (1978, based on Chrétien de Troyes's Le Conte del Graal), and perhaps John Boorman's Excalibur (1981, based on Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur).

Although clearly a major strand, retellings and reimaginings of Arthurian romance are not the only important aspect of the modern Arthurian legend. Attempts to envisage Arthur as a genuine historical figure of c.500 AD, stripping away the 'romance' elements to a greater or lesser degree, also play a significant role. As Taylor and Brewer have noted, this return to the medieval "chronicle tradition" of Geoffrey of Monmouth and the Historia Brittonum is a relatively recent trend which became dominant in Arthurian literature in the years following the outbreak of the Second World War, perhaps initially because of a combination of the weakening of the chivalric and romance ethos (referenced above) and the fact that the historical Arthur's resistance to Germanic invaders struck a certain cord in Britain after this time. So, Clemence Dane's series of radio plays, The Saviours (1942), made use of a historical Arthur in their invocation of a heroic spirit of resistance against desperate odds, and Robert Sherriff's play The Long Sunset (1955) saw Arthur rallying the Romano-British resistance against the Germanic invaders. The literary dominance of this desire to place Arthur in a historical, rather than a High Medieval romantic, mileu is also clear from novels published in this period, both true historical fictions and fantasy novels: for example, Stephen Lawhead's Pendragon Cycle (1987-99); Nikolai Tolstoy's The Coming of the King (1988); Jack Whyte's Camulod Chronicles (1992-97) and Bernard Cornwell's The Warlord Chronicles (1995-97). In recent years the portrayal of Arthur as a real, non-romance, hero of the 5th century has also made inroads into film versions of the Arthurian legend, most notably King Arthur (2004) and The Last Legion (2007).

Aspects of the legend

Weapons

In Culhwch and Olwen and the Welsh Bruts, Arthur's sword is called Caledfwlch (derived from caled, "battle, hard" + bwlch, "breach, gap, notch"). It is often considered to be related to the phonetically similar Caladbolg, a sword borne by several figures from Irish mythology, although a borrowing of Caledfwlch from Irish Caladbolg has been considered unlikely by Bromwich and Evans. They suggest instead that both names "may have similarly arisen at a very early date as generic names for a sword"; this sword then became exclusively the property of Arthur in the British tradition. Geoffrey of Monmouth calls Arthur's sword Caliburnus, a name which most Celticists consider to be derivative of a lost Old Welsh text in which bwlch had not yet been lenited to fwlch. In early French sources this then became Escalibor, and finally the familiar Excalibur.

In Arthurian romance a number of explanations are given for Arthur's possession of Excalibur. In Robert de Boron's Merlin, Arthur obtained the throne by pulling a sword from a stone. In this account, this act could not be performed except by "the true king," meaning the divinely appointed king or true heir of Uther Pendragon. This sword is thought by many to be the famous Excalibur and the identity is made explicit in the later so-called Vulgate Merlin Continuation, part of the Lancelot-Grail cycle. However, in what is sometimes called the Post-Vulgate Merlin, Excalibur was given to Arthur by the Lady of the Lake sometime after he began to reign. In the Vulgate Mort Artu, Arthur orders Girflet to throw the sword into the enchanted lake. After two failed attempts he finally complies with the wounded king's request and a hand emerges from the lake to catch it, a tale which becomes attached to Bedivere instead in Malory and the English tradition .

Excalibur is by no means the only weapon associated with Arthur, nor the only sword. Welsh tradition also knew of a dagger named Carnwennan and a spear named Rhongomyniad that belonged to him. Carnwennan ("Little White-Hilt") first appears in Culhwch and Olwen, where it was used by Arthur to slice the Very Black Witch in half. Rhongomyniad ("spear" + "striker, slayer") is also first mentioned in Culhwch, although only in passing; it appears as simply Ron ("spear") in Geoffrey's Historia. In the Alliterative Morte Arthure, a Middle English poem, there is mention of Clarent, a sword of peace meant for knighting and ceremonies as opposed to battle, which is stolen and then used to kill Arthur.

Family

In non-Galfridian Welsh Arthurian literature Arthur was granted numerous relations and family members. Several early Welsh sources are usually taken as indicative of Uther Pendragon being known as Arthur's father before Geoffrey wrote, with Arthur also being granted a brother (Madog) and a nephew ( Eliwlod) in these texts. Similarly, as Bromwich and Evans have observed, Culhwch and Olwen, the Vita Iltuti and the Brut Dingestow combine to suggest that Arthur was assigned a mother too - Eigyr - as well as maternal aunts, uncles, cousins and a grandfather called Anlawd Wledig. Arthur would seem to have had a sister, as Gwalchmei is named as his sister-son (nephew) in Culhwch, Gwalchmei's mother being one Gwyar. Turning to Arthur's own family, his wife is consistently stated to be Gwenhwyfar, usually the daughter of Ogrfan Gawr (Ogrfan "the Giant"), although Culhwch and Bonedd yr Arwyr do indicate that Arthur also had some sort of relationship with Eleirch daughter of Iaen, which produced a son named Kyduan. Kyduan was not the only child of Arthur according to Welsh Arthurian tradition - he is also ascribed sons called Duran, ., Amr, Gwydre, and Llacheu.

Relatively few members of Arthur's family in the Welsh materials are carried over to the works of Geoffrey and the romancers. His grandfather Anlawd Wledig and his maternal uncles, aunts and cousins do not appear there and neither do any of his sons or his paternal relatives. Only the core family seem to have made the journey: his wife Gwenhwyfar (who became Guinevere), his father Uther, his mother ( Igerna) and his sister-son Gwalchmei ( Gawain). As Roberts has noted, Gwalchmei's mother - Arthur's sister - failed to make the journey, Gwyar's place being taken by Anna, the wife of Loth, in Geoffrey's account, whilst Medraut ( Mordred) is made into a second sister-son for Arthur (a status he does not have in the Welsh material). In addition, new family members enter the Arthurian tradition from this point onwards. Uther is given a new family, including a brother and a father, while Arthur gains a sister, Morgan le Fay (first identified as Arthur's sister by Chrétien de Troyes), and a new son, Loholt, in Chrétien's Eric and Enide, the Perlesvaus and the Vulgate Cycle.

Another significant new family-member is Arthur's half-sister Morgause, the daughter of Gorlois and Igerna and mother of Gawain and Mordred in the French romances (replacing Geoffrey of Monmouth's Anna in this role). In the Vulgate Mort Artu we find Mordred's relationship with Arthur once more reinterpreted, as he is made the issue of an unwitting incestuous liaison between Arthur and this Morgause, with Arthur dreaming that Mordred would grow up to kill him. This tale is preserved in all the romances based on the Mort Artu and by the time we reach Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur Arthur has started to plot, Herod-like, to kill all children born on the same day as Mordred in order to save himself from this fate.

Although Arthur is given sons in both early and late Arthurian tales, he is rarely granted significant further generations of descendents; this is at least partly because of the premature deaths of his sons in these legends. Amr is the first to be mentioned in Arthurian literature, appearing in the 9th century Historia Brittonum':

- There is another wonder in the region which is called Ercing. A tomb is located there next to a spring which is called Licat Amr; and the name of the man who is buried in the tomb was called thus: Amr. He was the son of Arthur the soldier, and Arthur himself killed and buried him in that very place. And men come to measure the grave and find it sometimes six feet in length, sometimes nine, sometimes twelve, sometimes fifteen. At whatever length you might measure it at one time, a second time you will not find it to have the same length--and I myself have put this to the test.

Why Arthur chose to kill his son is never made clear. The only other reference to Amr comes in the post-Galfridian Welsh romance Geraint, where "Amhar son of Arthur" is one of Arthur’s four chamberlains along with Bedwyr’s son, Amhren. Gwydre is similarly unlucky, being slaughtered by the giant boar Twrch Trwyth in Culhwch and Olwen, along with two of Arthur's maternal uncles -- no other references to either Gwydre or Arthur's uncles survive. More is known of Arthur's son Llacheu. He is one of the "Three Well-Endowed Men of the Island of Britain", according to Triad number 4, and he fights alongside Cei in the early Arthurian poem Pa gur yv y porthaur?. Like his father is in Y Gododdin, Llacheu appears in 12th century and later Welsh poetry as a standard of heroic comparison and he also seems to have been similarly a figure of local topographic folklore too. Taken together, it is generally agreed that all these references indicate that Llacheu was a figure of considerable importance in the early Arthurian cycle. Nonetheless, Llacheu too dies, with the speaker in the pre-Galfridian poem Ymddiddan Gwayddno Garanhir ac Gwyn fab Nudd remembering that he had "been where Llacheu was slain / the son of Arthur, awful in songs / when ravens croaked over blood". Finally, Loholt is treacherously killed by Sir Kay so that the latter can take credit for the defeat of the giant Logrin in the Perlesvaus, while another son, known only from a possibly 15th century Welsh text, is said to have died on the field of Camlann:

- Sandde Bryd Angel drive the crow

- off the face of ?Duran [son of Arthur].

- Dearly and belovedly his mother raised him.

- Arthur sang it

- off the face of ?Duran [son of Arthur].

Medraut/Mordred is an exception to this. He, like Amr, is killed by Arthur - at Camlann in this case, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth and the post-Galfridian tradition. Mordred did, however, have two sons, who rose against Arthur's successor Constantine with the help of the Saxons (although it should be remembered that in Geoffrey's Historia Mordred is not yet Arthur's son).

Messianic return

The possibility of Arthur's return is first mentioned by William of Malmesbury in the early 12th century: "But Arthur’s grave is nowhere seen, whence antiquity of fables still claims that he will return." As Constance Bullock-Davies demonstrated, this belief in Arthur's eventual messianic return was extremely widespread amongst the Britons from the 12th century onwards — how much earlier than this it existed is still debated — and was often linked to the expulsion of the English and Normans from Britain, for which belief William of Newburgh and others mocked the Britons: "most of the Britons are thought to be so dull that even now they are said to be awaiting the coming of Arthur." This did, in fact, remain a powerful aspect of the Arthurian legend through the medieval period and beyond. So John Lydgate in his Fall of Princes (1431-8) notes the belief that Arthur "shall resorte as lord and sovereyne Out of fayrye and regne in Breteyne" and Philip II of Spain apparently swore, at the time of his marriage to Mary Tudor in 1554, that he would resign the kingdom if Arthur should return.

A number of locations were suggested for where Arthur would actually return from. The earliest-recorded suggestion was Avalon. In Geoffrey of Monmouth's 12th century Historia Regum Britanniae it is asserted that Arthur "was mortally wounded" at Camlann but was then carried "to the Isle of Avallon (insulam Auallonis) to be cured of his wounds", with the implication that he would at some point be cured and return therefrom made explicit in Geoffrey's later Vita Merlini Another tradition held that Arthur was awaiting his return beneath some mountain or hill. First referenced by Gervase of Tilbury in his Otia Imperialia (c.1211), this was maintained in British folklore into the 19th century and Loomis and others have taken it as a tale of Arthur's residence in an underground (as opposed to an overseas) Otherworld. Other less common concepts include the idea that Arthur was absent leading the Wild Hunt, or that he had been turned into a crow or raven.

This idea of Arthur's eventual return has proven attractive to a number of modern writers. John Masefield used the idea of Arthur sleeping under a hill as the central theme in his poem Midsummer Night (1928). C. S. Lewis also was inspired by this aspect of Arthur's legend in his novel That Hideous Strength (1945). Finally, Mike Barr and Brian Bolland have Arthur and his knights returning in the year 3000 to save the Earth from an alien invasion in Camelot 3000 (1982-85).

Cultural and political influence

The influence of Arthur's legend is not confined to novels, stories and films; he has also had a profound impact on popular culture and politics, especially in Britain and America. The legend of Arthur's messianic return has often been particularly influential from a political perspective. On the one hand it seems to have provided a means of rallying Welsh resistance to Norman incursions in the 12th century and afterwards, with one Anglo-Norman text recounting of the Welsh that "openly they go about saying,... / that in the end they will have it all; / by means of Arthur, they will have it back... / They will call it Britain again." On the other, the notion of Arthur's eventual return to rule a united Britain was harnessed by the Plantagenet kings as political propaganda to justify their rule through the naming of Richard I's heir as Arthur. Furthermore, once King Arthur had been safely pronounced dead and buried at Glastonbury, in an attempt to deflate Welsh dreams of a genuine Arthurian return, the Plantagenets were then able to make ever greater used of Arthur as a political cult to support their dynasty and its ambitions. So, Richard I used his status as the inheritor of Arthur's realm to shore up foreign alliances, giving a sword reputed to be Excalibur to Tancred of Sicily. Similarly, ' Round Tables' — jousting and dancing in imitation of Arthur and his knights — occurred at least 8 times in England between 1242 and 1345, including one held by Edward I in 1284 to celebrate his conquest of Wales and consequent 're-unification' of Arthurian Britain. The Galfridian claim that Arthur conquered Scotland was also used by Edward I to provide legitimacy to his claims of English suzerainty over that region too.

The influence of King Arthur on the political machinations of England's kings was not confined to the medieval period: the Tudors also found it expedient to make use of Arthur. In 1485 Henry VII marched through Wales to take the English throne under the banner of the Arthurian Red Dragon, he commissioned genealogies to show his putative decent from Arthur, and named his first-born son Arthur. Later, in the reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth Arthur's career was influential once again, now in providing evidence for supposed historical rights and territories in legal cases that pursued the crown's interests. Whilst the potential for such political usage — wherein the reality of Geoffrey's Arthur and his wide-ranging conquests was accepted and proclaimed by English antiquarians and thus utilised by the crown — naturally declined after the attacks on Geoffrey's Historia by Polydore Vergil and others, Arthur has remained an occasionally politically potent figure through to the present era. A notable example of this comes from 20th century America, where a comparison of John F. Kennedy and his Whitehouse with Arthur and Camelot, made by Kennedy's widow, helped cement and consolidate Kennedy's post-humous reputation, with Kennedy even becoming associated with an Arthur-like messianic return in American folklore.

Arthur's impact on popular culture has also been very significant. There have, for example, been attempts to use Arthur as a model for modern-day behaviour. In Britain the Order of the Fellowship of the Knights of the Round Table — based at King Arthur's Great Hall at Tintagel — existed in the 1930s to promote Christian ideals and Arthurian notions of medieval chivalry. Similarly, in America hundreds of thousands of boys and girls joined Arthurian youth groups, such as the Knights of King Arthur, in which Arthur and his legends were provided to them as wholesome examples to be emulated. However, the penetration of Arthur goes beyond such obviously Arthurian endeavours, with Arthurian names being regularly attached to objects, buildings and places. In Britain a whole class of locomotives, in use from 1925 until the 1960s, were named after King Arthur, whilst in Los Angeles the then-largest hotel in the world (opened in 1990) was named The Excalibur and there is even a US brand of flour named after Arthur. Arthur can also be found making appearances in numerous non-Arthurian television series, such as the Babylon 5 episode " A Late Delivery from Avalon", and comics — Lupack and Lupack note that almost all of the major comic book characters, including Spider-Man, Superman and the Fantastic Four, have had at least one Arthurian adventure. As Norris Lacy has observed, "The popular notion of Arthur appears to be limited, not surprisingly, to a few motifs and names, but there can be no doubt of the extent to which a legend born many centuries ago is profoundly embedded in modern culture at every level."