Mandelbrot set

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Mathematics

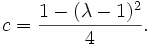

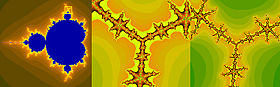

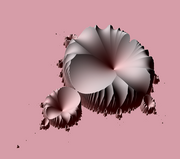

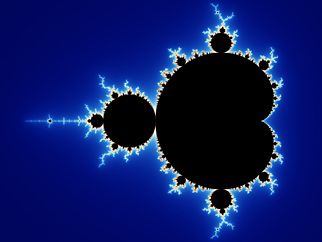

The Mandelbrot set is a set of points in the complex plane, the boundary of which forms a fractal. Mathematically, the Mandelbrot set can be defined as the set of complex c-values for which the orbit of 0 under iteration of the complex quadratic polynomial xn+1=xn2 + c remains bounded.

Eg. c = 1 gives the sequence 0, 1, 2, 5, 26… which leads to infinity. As this sequence is unbounded, 1 is not an element of the Mandelbrot set.

On the other hand, c = i gives the sequence 0, i, (-1 + i), –i, (-1 + i), -i… which is bounded, and so it belongs to the Mandelbrot set.

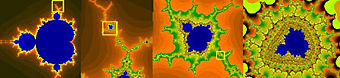

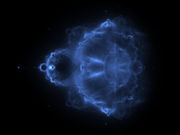

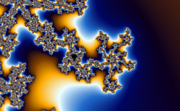

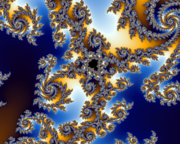

When computed and graphed on the complex plane, the Mandelbrot Set is seen to have an elaborate boundary, which does not simplify at any given magnification. This qualifies the boundary as a fractal.

The Mandelbrot set has become popular outside mathematics both for its aesthetic appeal and for being a complicated structure arising from a simple definition. Benoît Mandelbrot and others worked hard to communicate this area of mathematics to the public.

History

The Mandelbrot set has its place in complex dynamics, a field first investigated by the French mathematicians Pierre Fatou and Gaston Julia at the beginning of the 20th century. The first pictures of it were drawn in 1978 by Robert Brooks and Peter Matelski as part of a study of Kleinian Groups.

Mandelbrot studied the parameter space of quadratic polynomials in an article that appeared in 1980. The mathematical study of the Mandelbrot set really began with work by the mathematicians Adrien Douady and John H. Hubbard, who established many of its fundamental properties and named the set in honour of Mandelbrot.

The mathematicians Heinz-Otto Peitgen and Peter Richter became well-known for promoting the set with glossy photographs, books, and a touring gallery.

The cover article of the August 1985 Scientific American featured an image created by Mandelbrot, Peitgen, and Hubbard.

The work of Douady and Hubbard coincided with a huge increase in interest in complex dynamics and abstract mathematics, and the study of the Mandelbrot set has been a centerpiece of this field ever since. An exhaustive list of all the mathematicians who have contributed to the understanding of this set since then is beyond the scope of this article, but such a list would notably include Mikhail Lyubich, , Curt McMullen, John Milnor, Mitsuhiro Shishikura, and Jean-Christophe Yoccoz.

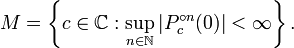

Formal definition

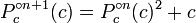

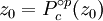

The Mandelbrot set M is defined by a family of complex quadratic polynomials

given by

,

,

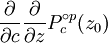

where c is a complex parameter. For each c, one considers the behaviour of the sequence  obtained by iterating Pc(z) starting at critical point

obtained by iterating Pc(z) starting at critical point  , which either escapes to infinity or stays within a disk of some finite radius. The Mandelbrot set is defined as the set of all points c such that the above sequence does not escape to infinity.

, which either escapes to infinity or stays within a disk of some finite radius. The Mandelbrot set is defined as the set of all points c such that the above sequence does not escape to infinity.

More formally, if  denotes the nth iterate of Pc(z) (i.e. Pc(z) composed with itself n times), the Mandelbrot set is the subset of the complex plane given by

denotes the nth iterate of Pc(z) (i.e. Pc(z) composed with itself n times), the Mandelbrot set is the subset of the complex plane given by

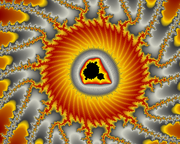

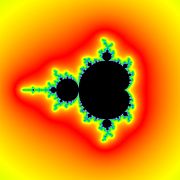

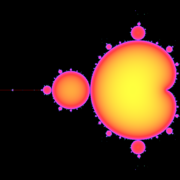

Mathematically, the Mandelbrot set is just a set of complex numbers. A given complex number c either belongs to M or it does not. A picture of the Mandelbrot set can be made by colouring all the points c which belong to M black, and all other points white. The more colourful pictures usually seen are generated by colouring points not in the set according to how quickly or slowly the sequence  diverges to infinity. See the section on computer drawings below for more details.

diverges to infinity. See the section on computer drawings below for more details.

The Mandelbrot set can also be defined as the connectedness locus of the family of polynomials Pc(z). That is, it is the subset of the complex plane consisting of those parameters c for which the Julia set of Pc is connected.

Basic properties

The Mandelbrot set is a compact set, contained in the closed disk of radius 2 around the origin. In fact, a point c belongs to the Mandelbrot set if and only if  for all

for all  . In other words, if the absolute value of

. In other words, if the absolute value of  ever becomes larger than 2, the sequence will escape to infinity.

ever becomes larger than 2, the sequence will escape to infinity.

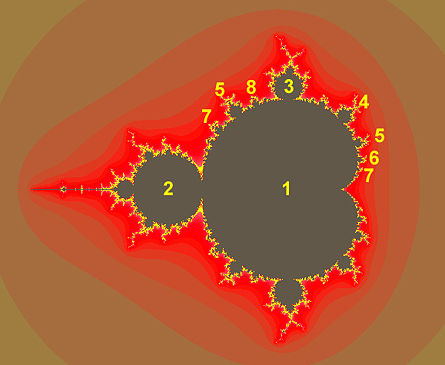

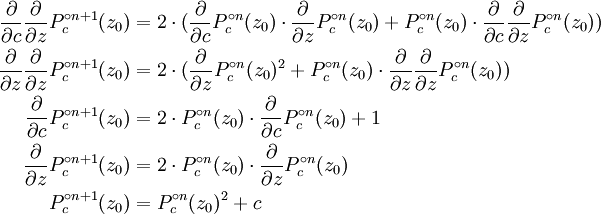

The intersection of M with the real axis is precisely the interval ![[-2 , 0.25]\,](../../images/312/31263.png) . The parameters along this interval can be put in one-to-one correspondence with those of the real logistic family,

. The parameters along this interval can be put in one-to-one correspondence with those of the real logistic family,

The correspondence is given by

In fact, this gives a correspondence between the entire parameter space of the logistic family and that of the Mandelbrot set.

The area of the Mandelbrot set is estimated to be 1.506 591 77 ± 0.000 000 08.

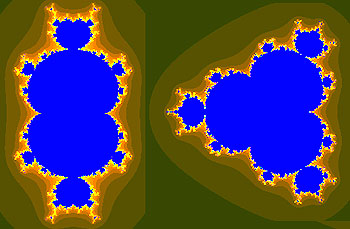

Douady and Hubbard have shown that the Mandelbrot set is connected. In fact, they constructed an explicit conformal isomorphism between the complement of the Mandelbrot set and the complement of the closed unit disk. Mandelbrot had originally conjectured that the Mandelbrot set is disconnected. This conjecture was based on computer pictures generated by programs which are unable to detect the thin filaments connecting different parts of M. Upon further experiments, he revised his conjecture, deciding that M should be connected.

The dynamical formula for the uniformisation of the complement of the Mandelbrot set, arising from Douady and Hubbard's proof of the connectedness of M, gives rise to external rays of the Mandelbrot set. These rays can be used to study the Mandelbrot set in combinatorial terms and form the backbone of the Yoccoz parapuzzle.

The boundary of the Mandelbrot set is exactly the bifurcation locus of the quadratic family; that is, the set of parameters c for which the dynamics changes abruptly under small changes of c. It can be constructed as the limit set of a sequence of plane algebraic curves, the Mandelbrot curves, of the general type known as polynomial lemniscates. The Mandelbrot curves are defined by setting p0=z, pn=pn-12+z, and then interpreting the set of points |pn(z)|=1 in the complex plane as a curve in the real Cartesian plane of degree 2n+1 in x and y.

Other properties

The main cardioid and period bulbs

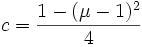

Upon looking at a picture of the Mandelbrot set, one immediately notices the large cardioid-shaped region in the centre. This main cardioid is the region of parameters c for which Pc has an attracting fixed point. It consists of all parameters of the form

for some  in the open unit disk.

in the open unit disk.

To the left of the main cardioid, attached to it at the point c = − 3 / 4, a circular-shaped bulb is visible. This bulb consists of those parameters  for which Pc has an attracting cycle of period 2. This set of parameters is an actual circle, namely that of radius 1/4 around -1.

for which Pc has an attracting cycle of period 2. This set of parameters is an actual circle, namely that of radius 1/4 around -1.

There are infinitely many other bulbs tangent to the main cardioid: for every rational number  , with p and q coprime, there is such a bulb that is tangent at the parameter

, with p and q coprime, there is such a bulb that is tangent at the parameter

This bulb is called the  -bulb of the Mandelbrot set. It consists of parameters which have an attracting cycle of period q and combinatorial rotation number

-bulb of the Mandelbrot set. It consists of parameters which have an attracting cycle of period q and combinatorial rotation number  . More precisely, the q periodic Fatou components containing the attracting cycle all touch at a common point (commonly called the

. More precisely, the q periodic Fatou components containing the attracting cycle all touch at a common point (commonly called the  -fixed point). If we label these components

-fixed point). If we label these components  in counterclockwise orientation, then Pc maps the component Uj to the component

in counterclockwise orientation, then Pc maps the component Uj to the component  .

.

The change of behaviour occurring at  is known as a bifurcation: the attracting fixed point "collides" with a repelling period q-cycle. As we pass through the bifurcation parameter into the

is known as a bifurcation: the attracting fixed point "collides" with a repelling period q-cycle. As we pass through the bifurcation parameter into the  -bulb, the attracting fixed point turns into a repelling fixed point (the α-fixed point), and the period q-cycle becomes attracting.

-bulb, the attracting fixed point turns into a repelling fixed point (the α-fixed point), and the period q-cycle becomes attracting.

Hyperbolic components

All the bulbs we encountered in the previous section were interior components of the Mandelbrot set in which the maps  have an attracting periodic cycle. Such components are called hyperbolic components.

have an attracting periodic cycle. Such components are called hyperbolic components.

It is conjectured that these are the only interior regions of M. This problem, known as density of hyperbolicity, may be the most important open problem in the field of complex dynamics. Hypothetical non-hyperbolic components of the Mandelbrot set are often referred to as "queer" components.

For real quadratic polynomials, this question was answered positively in the 1990s independently by Lyubich and by Graczyk and Świątek. (Note that hyperbolic components intersecting the real axis correspond exactly to periodic windows in the Feigenbaum diagram. So this result states that such windows exist near every parameter in the diagram.)

Not every hyperbolic component can be reached by a sequence of direct bifurcations from the main cardioid of the Mandelbrot set. However, such a component can be reached by a sequence of direct bifurcations from the main cardioid of a little Mandelbrot copy (see below).

Local connectivity

It is conjectured that the Mandelbrot set is locally connected. This famous conjecture is known as MLC (for Mandelbrot Locally Connected). By the work of Adrien Douady and John H. Hubbard, this conjecture would result in a simple abstract "pinched disk" model of the Mandelbrot set. In particular, it would imply the important hyperbolicity conjecture mentioned above.

The celebrated work of Jean-Christophe Yoccoz established local connectivity of the Mandelbrot set at all finitely-renormalizable parameters; that is, roughly speaking those which are contained only in finitely many small Mandelbrot copies. Since then, local connectivity has been proved at many other points of M, but the full conjecture is still open.

Self-similarity

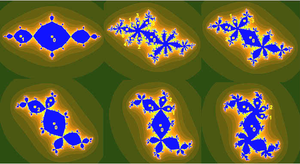

The Mandelbrot set is self-similar under magnification in the neighborhoods of the Misiurewicz points. It is also conjectured to be self-similar around generalized Feigenbaum points (e.g. -1.401155 or -.1528 + 1.0397i), in the sense of converging to a limit set.

The Mandelbrot set in general is not strictly self-similar but it is quasi-self-similar, as small slightly different versions of itself can be found at arbitrarily small scales.

The little copies of the Mandelbrot set are all slightly different, mostly because of the thin threads connecting them to the main body of the set.

Further results

The Hausdorff dimension of the boundary of the Mandelbrot set equals 2 as determined by a result of Mitsuhiro Shishikura. It is not known whether the boundary of the Mandelbrot set has positive planar Lebesgue measure.

In the Blum-Shub-Smale model of real computation, the Mandelbrot set is not computable, but its complement is computably enumerable. However, many simple objects (e.g., the graph of exponentiation) are also not computable in the BSS model. At present it is unknown whether the Mandelbrot set is computable in models of real computation based on computable analysis, which correspond more closely to the intuitive notion of "plotting the set by a computer." Hertling has shown that the Mandelbrot set is computable in this model if the hyperbolicity conjecture is true.

Relationship with Julia sets

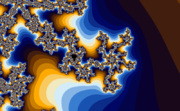

As a consequence of the definition of the Mandelbrot set, there is a close correspondence between the geometry of the Mandelbrot set at a given point and the structure of the corresponding Julia set.

This principle is exploited in virtually all deep results on the Mandelbrot set. For example, Shishikura proves that, for a dense set of parameters in the boundary of the Mandelbrot set, the Julia set has Hausdorff dimension two, and then transfers this information to the parameter plane. Similarly, Yoccoz first proves the local connectivity of Julia sets, before establishing it for the Mandelbrot set at the corresponding parameters. Adrien Douady phrases this principle as

Plough in the dynamical plane, and harvest in parameter space.

Geometry

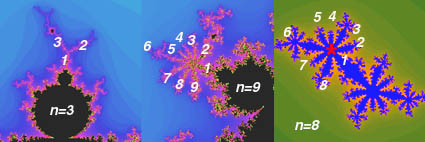

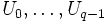

Recall that, for every rational number  , where p and q are relatively prime, there is a hyperbolic component of period q bifurcating from the main cardioid. The part of the Mandelbrot set connected to the main cardioid at this bifurcation point is called the p/q-limb. Computer experiments suggest that the diameter of the limb tends to zero like

, where p and q are relatively prime, there is a hyperbolic component of period q bifurcating from the main cardioid. The part of the Mandelbrot set connected to the main cardioid at this bifurcation point is called the p/q-limb. Computer experiments suggest that the diameter of the limb tends to zero like  . The best current estimate known is the famous Yoccoz-inequality, which states that the size tends to zero like

. The best current estimate known is the famous Yoccoz-inequality, which states that the size tends to zero like  .

.

A period q-limb will have q − 1 "antennae" at the top of its limb. We can thus determine the period of a given bulb by counting these antennas.

Generalizations

Sometimes the connectedness loci of families other than the quadratic family are also referred to as the Mandelbrot sets of these families.

The connectedness loci of the unicritical polynomial families  for d > 2 are often called Multibrot sets.

for d > 2 are often called Multibrot sets.

For general families of holomorphic functions, the boundary of the Mandelbrot set generalizes to the bifurcation locus, which is a natural object to study even when the connectedness locus is not useful.

It is also possible to consider similar constructions in the study of non-analytic mappings. Of particular interest is the tricorn, the connectedness locus of the anti-holomorphic family

The tricorn (also sometimes called the Mandelbar set) was encountered by Milnor in his study of parameter slices of real cubic polynomials. It is not locally connected. This property is inherited by the connectedness locus of real cubic polynomials.

Computer drawings

Algorithms :

- Escape time algorithm

- boolean version ( draws M-set and its exterior using 2 colours ) = Mandelbrot algorithm

- discrete (integer) version = level set method ( LSM/M ); draws Mandelbrot set and colour bands in its exterior

- continuous version

- level curves version = draws lemniscates of Mandelbrot set = boundaries of Level Sets

- decomposition of exterior of Mandelbrot set

- complex potential

- Hubbard-Douady (real) potential of Mandelbrot set (CPM/M) - radial part of complex potential

- external angle of Mandelbrot set - angular part of complex potential

- abstract M-set

- Distance estimation method for Mandelbrot set

- exterior distance estimation= Milnor algorithm (DEM/M)

- interior distance estimation

- algorithm used to explore interior of Mandelbrot set

- period of hyperbolic components

- multiplier of periodic orbit ( internal rays(angle) and intenal radius )

- bof61 and bof60

Every algorithm can be implemented in sequential or parallel version. Mirror symmetry can be used to speed-up calculations.

Escape time algorithm

The simplest algorithm for generating a representation of the Mandelbrot set is known as the "escape time" algorithm. A repeating calculation is performed for each x, y point in the plot area and based on the behaviour of that calculation, a colour is chosen for that pixel.

The x and y location of each point are used as starting values in a repeating, or iterating calculation (described in detail below). The result of each iteration is used as the starting values for the next. The values are checked during each iteration to see if they have reached a critical 'escape' condition. If that condition is reached, the calculation is stopped, the pixel is drawn, and the next x, y point is examined. For some starting values, escape occurs quickly, after only a small number of iterations. For other starting values, it may take hundreds or thousands of iterations to escape. For values within the Mandelbrot set, escape will never occur. The programmer or user must choose how much iteration, or 'depth,' they wish to examine. The higher the maximum number of iterations, the more detail and subtlety emerge in the final image, but the longer time it will take to calculate the picture.

The colour of each point represents how quickly the values reached the escape point. Often black is used to show values that fail to escape before the iteration limit, and gradually brighter colours are used for points that escape. This gives a visual representation of how many cycles were required before reaching the escape condition.

For programmers

The definition of the Mandelbrot set, together with its basic properties, suggests a simple algorithm for drawing a picture of the Mandelbrot set. The region of the complex plane we are considering is subdivided into a certain number of pixels. To colour any such pixel, let  be the midpoint of that pixel. We now iterate the critical value

be the midpoint of that pixel. We now iterate the critical value  under

under  , checking at each step whether the orbit point has modulus larger than 2.

, checking at each step whether the orbit point has modulus larger than 2.

If this is the case, we know that the midpoint does not belong to the Mandelbrot set, and we colour our pixel. (Either we colour it white to get the simple mathematical image or colour it according to the number of iterations used to get the well-known colourful images). Otherwise, we keep iterating for a certain (large, but fixed) number of steps, after which we decide that our parameter is "probably" in the Mandelbrot set, or at least very close to it, and colour the pixel black.

In pseudocode, this algorithm would look as follows.

For each pixel on the screen do:

{

x = x0 = x co-ordinate of pixel

y = y0 = y co-ordinate of pixel

iteration = 0

max_iteration = 1000

while ( x*x + y*y <= (2*2) AND iteration < max_iteration )

{

xtemp = x*x - y*y + x0

y = 2*x*y + y0

x = xtemp

iteration = iteration + 1

}

if ( iteration == max_iteration )

then

colour = black

else

colour = iteration

plot(x0,y0,colour)

}

where, relating the pseudocode to  and

and  :

:

- z = x + iy

- z2 = x2 + i2xy − y2

- c = x0 + iy0

and so, as can be seen in the pseudocode in the computation of x and y:

- x = Re(z2 + c) = x2 − y2 + x0 and y = Im(z2 + c) = 2xy + y0

To get colourful images of the set, the assignment of a colour to each value of the number of executed iterations can be made using one of a variety of functions (linear, exponential, etc). One practical way to do it, without slowing down the calculations, is to use the number of executed iterations as an entry to a look-up colour palette table initialized at startup. If the colour table has, for instance, 500 entries, then you can use n mod 500, where n is the number of iterations, to select the colour to use. You can initialize the colour palette matrix in various different ways, depending on what special feature of the escape behaviour you want to emphasize graphically.

Continuous (smooth) coloring

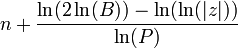

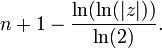

The Escape Time Algorithm is popular for its simplicity. However, it creates bands of colour, which can detract from an image's value. This can be fixed using the Normalized Iteration Count Algorithm, which provides a smooth transition of colors between iterations. The equation is

where n is the number of iterations for z, B is the bailout radius (it is normally 2 for a Mandelbrot set, but it can be changed), and P is the power for which z is raised to in the Mandelbrot set equation (zn+1=znP+c, P is generally 2). Another equation for this is

Note that this new equation is simpler than the first, but it only works for Mandelbrot sets with a bailout radius of 2 and a power of 2.

While this algorithm is relatively simple to implement (using either equation), there are a few things that need to be taken into consideration. First, the two equations return a continuous stream of numbers. However, it is up to you to decide on how the return values will be converted into a colour. Some type of method for casting these numbers onto a gradient should be developed. Second, it is recommended that a few extra iterations are done so that z can grow. If you stop iterating as soon as z escapes, there is the possibility that the smoothing algorithm will not work.

Distance estimates

One can compute distance from point c ( in exterior or interior ) to nearest point on the boundary of Mandelbrot set.

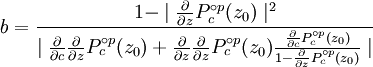

Exterior distance estimation

The proof of the connectedness of the Mandelbrot set in fact gives a formula for the uniformizing map of the complement of M (and the derivative of this map). By the Koebe 1/4 theorem, one can then estimate the distance between the mid-point of our pixel and the Mandelbrot set up to a factor of 4.

In other words, provided that the maximal number of iterations is sufficiently high, one obtains a picture of the Mandelbrot set with the following properties:

- Every pixel which contains a point of the Mandelbrot set is coloured black.

- Every pixel which is colored black is close to the Mandelbrot set.

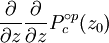

The distance estimate of a pixel c (a complex number) from the Mandelbrot set is given by

where

stands for complex quadratic polynomial

stands for complex quadratic polynomial stands for n iterations of

stands for n iterations of  or

or  , starting with z=c:

, starting with z=c:  ,

,  ;

; is the derivative of

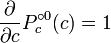

is the derivative of  with respect to c. This derivative can be found by starting with

with respect to c. This derivative can be found by starting with  and then

and then  . This can easily be verified by using the chain rule for the derivative.

. This can easily be verified by using the chain rule for the derivative.

From a mathematician's point of view, this formula only works in limit where n goes to infinity, but very reasonable estimates can be found with just a few additional iterations after the main loop exits.

Once b is found, by the Koebe 1/4-theorem, we know there's no point of the Mandelbrot set with distance from c smaller than b/4.

Interior distance estimation

It is also possible to estimate the distance of a limitly periodic (i.e., inner) point to the boundary of the Mandelbrot set. The estimate is given by

where

- p is the period,

- c is the point to be estimated,

- Pc(z) is the complex quadratic polynomial Pc(z) = z2 + c

is p compositions of

is p compositions of  , starting with

, starting with

- z0 is any of the p points that make the attractor of the iterations of

starting with

starting with  ; z0 satisfies

; z0 satisfies  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are various derivatives of

are various derivatives of  , evaluated at z0.

, evaluated at z0.

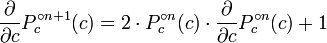

Given p and z0,  and its derivatives can be evaluated by:

and its derivatives can be evaluated by:

.

.

Analogous to the exterior case, once b is found, we know that all points within the distance of b/4 from c are inside the Mandelbrot set.

There are two practical problems with the interior distance estimate: first, we need to find z0 precisely, and second, we need to find p precisely. The problem with z0 is that the convergence to z0 by iterating Pc(z) requires, theoretically, an infinite number of operations. The problem with period is that, sometimes, due to rounding errors, a period is falsely identified to be an integer multiple of the real period (e.g., a period of 86 is detected, while the real period is only 43=86/2). In such case, the distance is overestimated, i.e., the reported radius could contain points outside the Mandelbrot set.

Optimizations

One way to improve calculations is to find out beforehand whether the given point lies within the cardioid or in the period-2 bulb.

To prevent having to do huge numbers of iterations for other points in the set, one can do "periodicity checking"—which means check if a point reached in iterating a pixel has been reached before. If so, the pixel cannot diverge, and must be in the set. This is most relevant for fixed-point calculations, where there is a relatively high chance of such periodicity—a full floating-point (or higher-accuracy) implementation would rarely go into such a period.

Periodicity checking is, of course, a trade-off: The need to remember points costs memory and data management instructions, whereas it saves computational instructions

![A mathematician's depiction of the Mandelbrot set M, a point c is coloured black if it belongs to the set, and white if not. Re[c] and Im[c] denote the real and imaginary parts of c.](../../images/312/31248.png)

![z\mapsto \lambda z(1-z),\quad \lambda\in[1,4].\,](../../images/312/31264.png)