Phishing

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Websites and the Internet

In computing, phishing is the criminally fraudulent process of attempting to acquire sensitive information such as usernames, passwords and credit card details, by masquerading as a trustworthy entity in an electronic communication. Communications purporting to be from PayPal, eBay, Youtube or online banks are commonly used to lure the unsuspecting. Phishing is typically carried out by e-mail or instant messaging, and it often directs users to enter details at a website. Phishing is an example of social engineering techniques used to fool users. Attempts to deal with the growing number of reported phishing incidents include legislation, user training, public awareness, and technical security measures.

A phishing technique was described in detail in 1987, and the first recorded use of the term "phishing" was made in 1996. The term is a variant of fishing, probably influenced by phreaking, and alludes to baits used to "catch" financial information and passwords.

History and current status of phishing

A phishing technique was described in detail in 1987, in a paper and presentation delivered to the International HP Users Group, Interex. The first recorded mention of the term "phishing" is on the alt.online-service.America-online Usenet newsgroup on January 2, 1996, although the term may have appeared earlier in the print edition of the hacker magazine 2600.

Early phishing on AOL

Phishing on AOL was closely associated with the warez community that exchanged pirated software. After AOL brought in measures in late 1995 to prevent using fake, algorithmically generated credit card numbers to open accounts, AOL crackers resorted to phishing for legitimate accounts.

A phisher might pose as an AOL staff member and send an instant message to a potential victim, asking him to reveal his password. In order to lure the victim into giving up sensitive information the message might include imperatives like "verify your account" or "confirm billing information". Once the victim had revealed the password, the attacker could access and use the victim's account for fraudulent purposes or spamming. Both phishing and warezing on AOL generally required custom-written programs, such as AOHell. Phishing became so prevalent on AOL that they added a line on all instant messages stating: "no one working at AOL will ask for your password or billing information".

After 1997, AOL's policy enforcement with respect to phishing and warez became stricter and forced pirated software off AOL servers. AOL simultaneously developed a system to promptly deactivate accounts involved in phishing, often before the victims could respond. The shutting down of the warez scene on AOL caused most phishers to leave the service, and many phishers—often young teens—grew out of the habit.

Transition from AOL to financial institutions

The capture of AOL account information may have led phishers to misuse credit card information, and to the realization that attacks against online payment systems were feasible. The first known direct attempt against a payment system affected E-gold in June 2001, which was followed up by a "post-911 id check" shortly after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Centre. Both were viewed at the time as failures, but can now be seen as early experiments towards more fruitful attacks against mainstream banks. By 2004, phishing was recognized as a fully industrialized part of the economy of crime: specializations emerged on a global scale that provided components for cash, which were assembled into finished attacks.

Recent phishing attempts

Phishers are targeting the customers of banks and online payment services. E-mails, supposedly from the Internal Revenue Service, have been used to glean sensitive data from U.S. taxpayers. While the first such examples were sent indiscriminately in the expectation that some would be received by customers of a given bank or service, recent research has shown that phishers may in principle be able to determine which banks potential victims use, and target bogus e-mails accordingly. Targeted versions of phishing have been termed spear phishing. Several recent phishing attacks have been directed specifically at senior executives and other high profile targets within businesses, and the term whaling has been coined for these kinds of attacks.

Social networking sites are a target of phishing, since the personal details in such sites can be used in identity theft; in late 2006 a computer worm took over pages on MySpace and altered links to direct surfers to websites designed to steal login details. Experiments show a success rate of over 70% for phishing attacks on social networks.

Almost half of phishing thefts in 2006 were committed by groups operating through the Russian Business Network based in St. Petersburg.

Phishing techniques

Filter evasion

Phishers have used images instead of text to make it harder for anti-phishing filters to detect text commonly used in phishing e-mails.

Website forgery

Once a victim visits the a phishing website the deception is not over. Some phishing scams use JavaScript commands in order to alter the address bar. This is done either by placing a picture of a legitimate URL over the address bar, or by closing the original address bar and opening a new one with the legitimate URL.

An attacker can even use flaws in a trusted website's own scripts against the victim. These types of attacks (known as cross-site scripting) are particularly problematic, because they direct the user to sign in at their bank or service's own web page, where everything from the web address to the security certificates appears correct. In reality, the link to the website is crafted to carry out the attack, although it is very difficult to spot without specialist knowledge. Just such a flaw was used in 2006 against PayPal.

A Universal Man-in-the-middle Phishing Kit, discovered by RSA Security, provides a simple-to-use interface that allows a phisher to convincingly reproduce websites and capture log-in details entered at the fake site.

To avoid anti-phishing techniques that scan websites for phishing-related text, phishers have begun to use Flash-based websites. These look much like the real website, but hide the text in a multimedia object.

Phone phishing

Not all phishing attacks require a fake website. Messages that claimed to be from a bank told users to dial a phone number regarding problems with their bank accounts. Once the phone number (owned by the phisher, and provided by a Voice over IP service) was dialed, prompts told users to enter their account numbers and PIN. Vishing (voice phishing) sometimes uses fake caller-ID data to give the appearance that calls come from a trusted organization.

Phishing examples

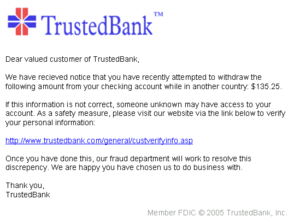

PayPal phishing example

In an example PayPal phish (right), spelling mistakes in the e-mail and the presence of an IP address in the link (visible in the tooltip under the yellow box) are both clues that this is a phishing attempt. Another giveaway is the lack of a personal greeting, although the presence of personal details would not be a guarantee of legitimacy. A legitimate Paypal communication will always greet the user with his or her real name, not just with a generic greeting like, "Dear Accountholder." Other signs that the message is a fraud are misspellings of simple words, bad grammar and the threat of consequences such as account suspension if the recipient fails to comply with the message's requests.

Note that many phishing emails will include, as a real email from PayPal would, large warnings about never giving out your password in case of a phishing attack. Warning users of the possibility of phishing attacks, as well as providing links to sites explaining how to avoid or spot such attacks, are part of what makes the phishing email so deceptive. In this example, the phishing email warns the user that emails from PayPal will never ask for sensitive information. True to its word, it instead invites the user to follow a link to "Verify" their account; this will take them to a further phishing website, engineered to look like PayPal's website, and will there ask for their sensitive information.

Damage caused by phishing

The damage caused by phishing ranges from denial of access to e-mail to substantial financial loss. This style of identity theft is becoming more popular, because of the readiness with which unsuspecting people often divulge personal information to phishers, including credit card numbers, social security numbers, and mothers' maiden names. There are also fears that identity thieves can add such information to the knowledge they gain simply by accessing public records. Once this information is acquired, the phishers may use a person's details to create fake accounts in a victim's name. They can then ruin the victims' credit, or even deny the victims access to their own accounts.

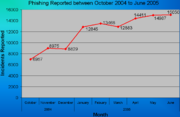

It is estimated that between May 2004 and May 2005, approximately 1.2 million computer users in the United States suffered losses caused by phishing, totaling approximately US$929 million. United States businesses lose an estimated US$2 billion per year as their clients become victims. In 2007 phishing attacks escalated. 3.6 million adults lost US $ 3.2 billion in the 12 months ending in August 2007. In the United Kingdom losses from web banking fraud—mostly from phishing—almost doubled to £23.2m in 2005, from £12.2m in 2004, while 1 in 20 computer users claimed to have lost out to phishing in 2005.

The stance adopted by the UK banking body APACS is that "customers must also take sensible precautions ... so that they are not vulnerable to the criminal." Similarly, when the first spate of phishing attacks hit the Irish Republic's banking sector in September 2006, the Bank of Ireland initially refused to cover losses suffered by its customers (and it still insists that its policy is not to do so), although losses to the tune of €11,300 were made good.

Anti-phishing

There are several different techniques to combat phishing, including legislation and technology created specifically to protect against phishing.

Social responses

One strategy for combating phishing is to train people to recognize phishing attempts, and to deal with them. Education can be effective, especially where training provides direct feedback. One newer phishing tactic, which uses phishing e-mails targeted at a specific company, known as spear phishing, has been harnessed to train individuals at various locations, including West Point Military Academy. In a June 2004 experiment with spear phishing, 80% of 500 West Point cadets who were sent a fake e-mail were tricked into revealing personal information.

People can take steps to avoid phishing attempts by slightly modifying their browsing habits. When contacted about an account needing to be "verified" (or any other topic used by phishers), it is a sensible precaution to contact the company from which the e-mail apparently originates to check that the e-mail is legitimate. Alternatively, the address that the individual knows is the company's genuine website can be typed into the address bar of the browser, rather than trusting any hyperlinks in the suspected phishing message.

Nearly all legitimate e-mail messages from companies to their customers contain an item of information that is not readily available to phishers. Some companies, for example PayPal, always address their customers by their username in e-mails, so if an e-mail addresses the recipient in a generic fashion ("Dear PayPal customer") it is likely to be an attempt at phishing. E-mails from banks and credit card companies often include partial account numbers. However, recent research has shown that the public do not typically distinguish between the first few digits and the last few digits of an account number—a significant problem since the first few digits are often the same for all clients of a financial institution. People can be trained to have their suspicion aroused if the message does not contain any specific personal information. Phishing attempts in early 2006, however, used personalized information, which makes it unsafe to assume that the presence of personal information alone guarantees that a message is legitimate. Furthermore, another recent study concluded in part that the presence of personal information does not significantly affect the success rate of phishing attacks, which suggests that most people do not pay attention to such details.

The Anti-Phishing Working Group, an industry and law enforcement association, has suggested that conventional phishing techniques could become obsolete in the future as people are increasingly aware of the social engineering techniques used by phishers. They predict that pharming and other uses of malware will become more common tools for stealing information.

Technical responses

Anti-phishing measures have been implemented as features embedded in browsers, as extensions or toolbars for browsers, and as part of website login procedures. The following are some of the main approaches to the problem.

Helping to identify legitimate sites

Since phishing is based on impersonation, preventing it depends on some reliable way to determine a website's real identity. For example, some anti-phishing toolbars display the domain name for the visited website. The petname extension for Firefox lets users type in their own labels for websites, so they can later recognize when they have returned to the site. If the site is suspect, then the software may either warn the user or block the site outright.

Browsers alerting users to fraudulent websites

Another popular approach to fighting phishing is to maintain a list of known phishing sites and to check websites against the list. Microsoft's IE7 browser, Mozilla Firefox 2.0, and Opera all contain this type of anti-phishing measure. Firefox 2 uses Google anti-phishing software. Opera 9.1 uses live blacklists from PhishTank and GeoTrust, as well as live whitelists from GeoTrust. Some implementations of this approach send the visited URLs to a central service to be checked, which has raised concerns about privacy. According to a report by Mozilla in late 2006, Firefox 2 was found to be more effective than Internet Explorer 7 at detecting fraudulent sites in a study by an independent software testing company.

An approach introduced in mid-2006 involves switching to a special DNS service that filters out known phishing domains: this will work with any browser, and is similar in principle to using a hosts file to block web adverts.

To mitigate the problem of phishing sites impersonating a victim site by embedding its images (such as logos), several site owners have altered the images to send a message to the visitor that a site may be fraudulent. The image may be moved to a new filename and the original permanently replaced, or a server can detect that the image was not requested as part of normal browsing, and instead send a warning image.

Augmenting password logins

The Bank of America's website is one of several that ask users to select a personal image, and display this user-selected image with any forms that request a password. Users of the bank's online services are instructed to enter a password only when they see the image they selected. However, a recent study suggests few users refrain from entering their password when images are absent. In addition, this feature (like other forms of two-factor authentication) is susceptible to other attacks, such as those suffered by Scandinavian bank Nordea in late 2005, and Citibank in 2006.

Security skins are a related technique that involves overlaying a user-selected image onto the login form as a visual cue that the form is legitimate. Unlike the website-based image schemes, however, the image itself is shared only between the user and the browser, and not between the user and the website. The scheme also relies on a mutual authentication protocol, which makes it less vulnerable to attacks that affect user-only authentication schemes.

Eliminating phishing mail

Specialized spam filters can reduce the number of phishing e-mails that reach their addressees' inboxes. These approaches rely on machine learning and natural language processing approaches to classify phishing e-mails.

Monitoring and takedown

Several companies offer banks and other organizations likely to suffer from phishing scams round-the-clock services to monitor, analyze and assist in shutting down phishing websites. Individuals can contribute by reporting phishing to both volunteer and industry groups, such as PhishTank.

Legal responses

On January 26, 2004, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission filed the first lawsuit against a suspected phisher. The defendant, a Californian teenager, allegedly created a webpage designed to look like the America Online website, and used it to steal credit card information. Other countries have followed this lead by tracing and arresting phishers. A phishing kingpin, Valdir Paulo de Almeida, was arrested in Brazil for leading one of the largest phishing crime rings, which in two years stole between US$18 million and US$37 million. UK authorities jailed two men in June 2005 for their role in a phishing scam, in a case connected to the U.S. Secret Service Operation Firewall, which targeted notorious "carder" websites. In 2006 eight people were arrested by Japanese police on suspicion of phishing fraud by creating bogus Yahoo Japan Web sites, netting themselves 100 million yen ($870,000 USD). The arrests continued in 2006 with the FBI Operation Cardkeeper detaining a gang of sixteen in the U.S. and Europe.

In the United States, Senator Patrick Leahy introduced the Anti-Phishing Act of 2005 in Congress on March 1, 2005. This bill, if it had been enacted into law, would have subjected criminals who created fake web sites and sent bogus e-mails in order to defraud consumers to fines of up to $250,000 and prison terms of up to five years. The UK strengthened its legal arsenal against phishing with the Fraud Act 2006, which introduces a general offence of fraud that can carry up to a ten year prison sentence, and prohibits the development or possession of phishing kits with intent to commit fraud.

Companies have also joined the effort to crack down on phishing. On March 31, 2005, Microsoft filed 117 federal lawsuits in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington. The lawsuits accuse " John Doe" defendants of obtaining passwords and confidential information. March 2005 also saw a partnership between Microsoft and the Australian government teaching law enforcement officials how to combat various cyber crimes, including phishing. Microsoft announced a planned further 100 lawsuits outside the U.S. in March 2006, followed by the commencement, as of November 2006, of 129 lawsuits mixing criminal and civil actions. AOL reinforced its efforts against phishing in early 2006 with three lawsuits seeking a total of $18 million USD under the 2005 amendments to the Virginia Computer Crimes Act, and Earthlink has joined in by helping to identify six men subsequently charged with phishing fraud in Connecticut.

In January 2007, Jeffrey Brett Goodin of California became the first defendant convicted by a jury under the provisions of the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003. He was found guilty of sending thousands of e-mails to America Online users, while posing as AOL's billing department, which prompted customers to submit personal and credit card information. Facing a possible 101 years in prison for the CAN-SPAM violation and ten other counts including wire fraud, the unauthorized use of credit cards, and the misuse of AOL's trademark, he was sentenced to serve 70 months. Goodin had been in custody since failing to appear for an earlier court hearing and began serving his prison term immediately.