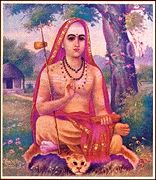

Adi Shankara

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Religious figures and leaders

| Adi Shankara | |

| Date of birth | circa 788 CE/AD |

|---|---|

| Place of birth | Kalady, Kerala, India |

| Birth name | Shankara |

| Date of passing | circa 820 CE |

| Place of passing | Kedarnath, Uttarakhand, India |

| Guru/Teacher | Govinda Bhagavatpada |

| Philosophy | Advaita Vedanta |

| Titles/Honours | Introduced Advaita Vedanta, Hindu Revivalism, Founded Dashanami Sampradaya, Shanmata |

| This article contains Indic text. Without rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes or other symbols instead of Indic characters; or irregular vowel positioning and a lack of conjuncts. |

Adi Shankara ( Malayalam: ആദി ശങ്കരന്, Devanāgarī: आदि शङ्कर, Ādi Śaṅkara, pronounced [aːd̪i ɕaŋkərə]); (possibly 788 – 820 CE, but see below), also known as Śaṅkara Bhagavatpādācārya ("the teacher at the feet of God"), and Ādi Śaṅkarācārya was the first philosopher to consolidate the doctrine of Advaita Vedanta, a sub-school of Vedanta. His teachings are based on the unity of the soul and Brahman, in which Brahman is viewed as without attributes. In the Smārta tradition, Adi Shankara is regarded as an incarnation of Shiva.

Adi Shankara toured India with the purpose of propagating his teachings through discourses and debates with other philosophers. He founded four mathas ("monasteries") which played a key role in the historical development, revival and spread of post-Buddhist Hinduism and Advaita Vedanta. Adi Shankara was the founder of the Dashanami monastic order and the Shanmata tradition of worship.

His works in Sanskrit, all of which are extant today, concern themselves with establishing the doctrine of Advaita ( Nondualism). Adi Shankara quotes extensively from the Upanishads and other Hindu scriptures in forming his teachings. He also includes arguments against opposing schools of thought like Samkhya and Buddhism in his works.

Life

The traditional accounts of Adi Shankara's life are called the Shankara Vijayams, ("Victory of Shankara"). These are poetic works containing a mix of biographical and legendary material, written in the epic style. The most important among these biographies are the Mādhavīya Śaṅkara Vijayaṃ (of Mādhava, c. 14th century), the Cidvilāsīya Śaṅkara Vijayaṃ (of Cidvilāsa, c. between 15th century and 17th century), and the Keraļīya Śaṅkara Vijayaṃ (of the Kerala region, extant from c. 17th century). According to these texts, Adi Shankara was born in Kalady, a village in Kerala, India, to a Namboothiri brahmin couple, Shivaguru and Aryamba and lived for thirty-two years.

Birth and childhood

Adi Shankara's parents, Kaippilly Sivaguru Nambudiri and Arya Antharjanam (Melpazhur Mana), were childless for many years. They prayed at the Vadakkunnathan temple (also known as Vrishabhachala) in Thrissur, Kerala, for the birth of a child. Legend has it that Shiva appeared to both husband and wife in their dreams, and offered them a choice: a mediocre son who would live a long life, or an extraordinary son who would not live long. Both the parents chose the latter; thus a son was born to them. He was named Shankara (Sanskrit, "bestower of goodness"), in honour of Shiva (one of whose epithets is Shankara).

His father died while Shankara was very young. Shankara's upanayanaṃ, the initiation into student-life, was performed at the age of five. As a child, Shankara showed remarkable scholarship, mastering the four Vedas by the age of eight. Following the customs of those days, Shankara studied and lived at the home of his teacher. It was customary for students and men of learning to receive Bhikṣā ("alms") from the laity; on one occasion, while accepting Bhikṣā, Shankara came upon a woman who had only a single dried amalaka fruit to eat. Rather than consuming this last bit of food herself, the lady gave away the fruit to Shankara as Bhikṣā. Moved by her piety, Shankara composed the Kanakadhārā Stotram on the spot. Legend has it that on completion of this stotra, golden amalaka fruits were showered upon the woman by Lakṣmi, the Goddess of wealth.

Sannyasa

From a young age, Shankara was inclined towards sannyasa ("monastic life"). His mother was against his becoming a monk, and refused him formal permission. However, once when Shankara was bathing in the Periyar River near his house, a crocodile gripped his leg and began to drag him into the water. Only his mother was nearby, and it proved impossible for her to rescue him. Shankara asked his mother to give him permission to renounce the world then and there, so that he could be a sannyāsin at the moment of death. This mode of entering the renunciatory stage is called Āpat Sannyāsa. At the end of her wits, his mother agreed. Shankara immediately recited the mantras to make a renunciate of himself. Miraculously, the crocodile released him and swam away. Shankara emerged unscathed from the water.

With the permission of his mother, Shankara left Kerala and travelled towards North India in search of a Guru. On the banks of the Narmada River, he met Govinda Bhagavatpada, the disciple of Gaudapada. When Govinda Bhagavatpada asked Shankara's identity, he replied with an extempore verse that brought out the Advaita Vedanta philosophy. Govinda Bhagavatapada was impressed and took Shankara as his disciple. Adi Shankara was commissioned by his Guru to write a commentary on the Brahma Sutras and propagate Advaita Vedanta. The Mādhavīya Shankaravijaya states that Adi Shankara calmed a flood from the Reva River by placing his kamaṇḍalu ("water pot") in the path of the raging water, thus saving his Guru, Govinda Bhagavatpada, who was absorbed in Samādhi ("meditation") in a cave nearby.

On his mission to spread the Advaita Vedanta philosophy, Adi Shankara travelled to Kashi, where a young man named Sanandana from Choladesha in South India, became his first disciple. In Kashi, Adi Shankara was on his way to the Vishwanath Temple, when he came upon an untouchable with four dogs. When asked to move aside by Shankara's disciples, the untouchable replied: "Do you wish that I move my ever lasting Ātman ("the Self"), or this body made of food?" Understanding that the untouchable was none other than god Shiva, and his dogs the four Vedas, Shankara prostrated himself before him, composing five shlokas known as Manisha Panchakam.

On reaching Badari in the Himalayas, he wrote the famous Bhashyas ("commentaries") and Prakarana granthas ("philosophical treatises"). Afterwards he taught these commentaries to his disciples. Some, like Sanandana, were quick to grasp the essence; the other disciples thus became jealous of Sanandana. In order to convince the others of Sanandana's inherent superiority, Adi Shankara summoned Sanandana from one bank of the Ganga River, while he was on the opposite bank. Sanandana crossed the river by walking on the lotuses that were brought out wherever he placed his foot. Adi Shankara was greatly impressed by his disciple and gave him the name Padmapāda ("lotus-footed one").

Meeting with Mandana Mishra

One of the most famous debates of Adi Shankara was with the ritualist Mandana Mishra. Mandana Mishra's Guru was the famous Mimamsa philosopher, Kumarīla Bhaṭṭa. Shankara sought a debate with Kumarīla Bhaṭṭa and met him in Prayag where he had buried himself in a slow burning pyre to repent for sins committed against his Guru: Kumarīla Bhaṭṭa had learnt Buddhist philosophy incognito from his Guru in order to be able to refute it. Learning anything without the knowledge of one's Guru while still under his authority constitutes a sin according to the Vedas. Kumarīla Bhaṭṭa thus asked Adi Shankara to proceed to Mahiṣmati (known today as Mahishi Bangaon, Saharsa in Bihar) to meet Mandana Mishra and debate with him instead.

Adi Shankara had a famous debate with Mandana Mishra in which the wife of Mandana Mishra, Ubhaya Bhāratī, was the referee. After debating for over fifteen days, Mandana Mishra accepted defeat. Ubhaya Bhāratī then challenged Adi Shankara to have a debate with her in order to 'complete' the victory. Later, Ubhaya Bhāratī concedes defeat in the debate and allows Mandana Mishra to accept sannyasa with the monastic name, Sureśvarācārya as per the agreed rules of the debate.

Missionary tour

Adi Shankara then travelled with his disciples to Maharashtra and Srisailam. In Srisailam, he composed Shivanandalahari, a devotional hymn to Shiva. The Madhaviya Shankaravijayam says that when Shankara was about to be sacrificed by a Kapalika, the God Narasimha appeared to save Shankara on Padmapada's prayer to him. So Adi Shankara composed the Laksmi-Narasimha stotra. He then travelled to Gokarṇa, the temple of Hari-Shankara and the Mūkambika temple at Kollur. At Kollur, he accepted as his disciple a boy believed to be dumb by his parents. He gave him the name, Hastāmalakācārya ("one with the amalaka fruit on his palm", i.e., one who has clearly realised the Self). Next, he visited Śṛngeri to establish the Śārada Pīṭham and made Toṭakācārya his disciple.

After this, Adi Shankara began a Dig-vijaya (missionary tour) for the propagation of the Advaita philosophy by controverting all philosophies opposed to it. He travelled throughout India, from the South to Kashmir and Nepal, preaching to the local populace and debating philosophy with Hindu, Buddhist and other scholars and monks along the way.

With the Malayali King Sudhanva as companion, Shankara passed through Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Vidarbha. He then started towards Karnataka where he encountered a band of armed Kapalikas. King Sudhanva, with his army, resisted and defeated the Kapalikas. They safely reached Gokarna where Shankara defeated in debate the Shaiva scholar, Neelakanta.

Proceeding to Saurashtra (the ancient Kambhoja) and having visited the shrines of Girnar, Somnath and Prabhasa and explaining the superiority of Vedanta in all these places, he arrived at Dwarka. Bhaṭṭa Bhāskara of Ujjayini, the proponent of Bhedābeda philosophy, was humbled. All the scholars of Ujjayini (also known as Avanti) accepted Adi Shankara's philosophy.

He then defeated the Jainas in philosophical debates at a place called Bahlika. Thereafter, the Acharya established his victory over several philosophers and ascetics in Kamboja (region of North Kashmir), Darada (Dabistan) and many regions situated in the desert and crossing mighty peaks, entered Kashmir. Later, he had an encounter with a tantrik, Navagupta at Kamarupa.

Accession to Sarvajnapitha

Adi Shankara visited Sarvajñapīṭha ( Sharada Peeth) in Kashmir (now in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir). The Madhaviya Shankaravijayam states this temple had four doors for scholars from the four cardinal directions. The southern door (representing South India) had never been opened, indicating that no scholar from South India had entered the Sarvajna Pitha. Adi Shankara opened the southern door by defeating in debate all the scholars there in all the various scholastic disciplines such as Mimamsa, Vedanta and other branches of Hindu philosophy; he ascended the throne of Transcendent wisdom of that temple.

Towards the end of his life, Adi Shankara travelled to the Himalayan area of Kedarnath- Badrinath and attained videha mukti ("freedom from embodiment"). There is a samadhi mandir dedicated to Adi Shankara behind the Kedarnath temple. However, there are variant traditions on the location of his last days. One tradition, expounded by Keraliya Shankaravijaya, places his place of death as Vadakkunnathan temple in Thrissur, Kerala. The followers of the Kanchi kamakoti pitha claim that he ascended the Sarvajñapīṭha and attained videha-mukti in Kanchipuram ( Tamil Nadu).

Dates

At least two different dates have been proposed for Shankara:

- 788–820 CE: This is the mainstream scholarly opinion, placing Shankara in mid to late 8th century CE. These dates are based on records at the Śṛṅgeri Śāradā Pīṭham, which is the only matha to have maintained a relatively unbroken record of its Acharyas; starting with the third Acharya, one can with reasonable confidence date the others from the 8th century down. The Sringeri records state that Sankara was born in the 14th year of the reign of "VikramAditya", but it is unclear as to which king this name may refer. Though some researchers identify the name with Chandragupta II (4th. c. AD), modern scholarship accepts the VikramAditya as being from the Chalukya dynasty of Badami, most likely Vikramaditya II (733–746 CE), which would place him in the middle of the 8th c. The date 788–820 is also among those considered acceptable by Swami Tapasyananda, though he raises a number of questions. It is also acceptable to Keay.

- 509 – 477 BCE: This dating, more than a millennium ahead of all others, is based on records of the heads of the Shankara Maṭhas at Dwaraka matha and Puri matha and the fifth Peetham at Kanchi. However, such an early date is not consistent with the fact that Sankara quotes the Buddhist logician Dharmakirti, who finds mention in Huen Tsang (7th c.). Also, his near-contemporary Kumarila Bhatta is usually dated ca. 8th c. AD. Most scholars feel that due to invasions and other discontinuities, the records of the Dwarka and Puri mathas are not as reliable as those for Sringeri.

Thus, while considerable debate exists, the pre-Christian Era dates are usually discounted, and the most likely period for Shankara is during the 8th c. CE.

Mathas

Adi Shankara founded four Maṭhas (Sanskrit: मठ) to guide the Hindu religion. These are at Sringeri in Karnataka in the south, Dwaraka in Gujarat in the west, Puri in Orissa in the east, and Jyotirmath (Joshimath) in Uttarakhand in the north. Hindu tradition states that he put in charge of these mathas his four main disciples: Sureshwaracharya, Hastamalakacharya, Padmapadacharya, and Totakacharya respectively. The heads of the mathas trace their authority back to these figures. Each of the heads of these four mathas takes the title of Shankaracharya ("the learned Shankara") after the first Shankaracharya. The table below gives an overview of the four Amnaya Mathas founded by Adi Shankara and their details.

| Śishya | Maṭha | Mahāvākya | Veda | Sampradaya |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hastāmalakācārya | Govardhana Pīṭhaṃ | Prajñānam brahma (Brahman is Knowledge) | Rig Veda | Bhogavala |

| Sureśvarācārya | Śārada Pīṭhaṃ | Aham brahmāsmi (I am Brahman) | Yajur Veda | Bhūrivala |

| Padmapādācārya | Dvāraka Pīṭhaṃ | Tattvamasi (That thou art) | Sama Veda | Kitavala |

| Toṭakācārya | Jyotirmaṭha Pīṭhaṃ | Ayamātmā brahma (This Atman is Brahman) | Atharva Veda | Nandavala |

Philosophy and religious thought

Advaita ("non-dualism") is often called a monistic system of thought. The word "Advaita" essentially refers to the identity of the Self ( Atman) and the Whole (Brahman). The key source texts for all schools of Vedānta are the Prasthanatrayi– the canonical texts consisting of the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutras.

Adi Shankara was the first in its tradition to consolidate the siddhānta ("doctrine") of Advaita Vedanta. He wrote commentaries on the Prasthana Trayi. A famous quote from Vivekacūḍāmaṇi, one of his prakarana granthas that succinctly summarises his philosophy is:

Brahma satyaṃ jagat mithyā, jīvo brahmaiva nāparah

Brahman is the only truth, the world is unreal, and there is ultimately no difference between Brahman and individual self.

Advaita Vedanta is based on śāstra ("scriptures"), yukti ("reason") and anubhava ("experience"), and aided by karmas ("spiritual practices"). This philosophy provides a clear-cut way of life to be followed. Starting from childhood, when learning has to start, the philosophy has to be realised in practice throughout one's life even up to death. This is the reason why this philosophy is called an experiential philosophy, the underlying tenet being "That thou art", meaning that ultimately there is no difference between the experiencer and the experienced (the world) as well as the universal spirit (Brahman). Among the followers of Advaita, as well those of other doctrines, there are believed to have appeared Jivanmuktas, ones liberated while alive. These individuals (commonly called Mahatmas, great souls, among Hindus) are those who realised the oneness of their self and the universal spirit called Brahman. Some of the Translated philosophies of Adi Shankara are - Adi Sanakara Philosophy.

Adi Shankara's Bhashyas (commentaries) on the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutras are his principal and almost undeniably his own works. Although he mostly adhered to traditional means of commenting on the Brahma Sutra, there are a number of original ideas and arguments to establish that the essence of Upanishads is Advaita. He taught that it was only through direct knowledge of Brahman that one could be enlightened.

Adi Shankara's opponents accused him of teaching Buddhism in the garb of Hinduism, because his non-dualistic ideals were a bit radical to contemporary Hindu philosophy. However, it may be noted that while the Later Buddhists arrived at a changeless, deathless, absolute truth after their insightful understanding of the unreality of samsara, historically Vedantins never liked this idea. Although Advaita proposes the theory of Maya, explaining the universe as a "trick of a magician", Adi Shankara and his followers see this as a consequence of their basic premise that Brahman alone is real. Their idea of Maya emerges from their belief in the reality of Brahman, rather than the other way around.

Historical and cultural impact

At the time of Adi Shankara's life, Hinduism had begun to decline because of the influence of Buddhism and Jainism. Hinduism had become divided into innumerable sects, each quarrelling with the others. The followers of Mimamsa and Sankhya philosophy were atheists, insomuch that they did not believe in God as a unified being. Besides these atheists, there were numerous theistic sects. There were also those who rejected the Vedas, like the Charvakas.

Adi Shankara held discourses and debates with the leading scholars of all these sects and schools of philosophy to controvert their doctrines. He unified the theistic sects into a common framework of Shanmata system. In his works, Adi Shankara stressed the importance of the Vedas, and his efforts helped Hinduism regain strength and popularity. Many trace the present worldwide domination of Vedanta to his works. He travelled on foot to various parts of India to restore the study of the Vedas.

Even though he lived for only thirty-two years, his impact on India and on Hinduism was striking. He reintroduced a purer form of Vedic thought. His teachings and tradition form the basis of Smartism and have influenced Sant Mat lineages. He is the main figure in the tradition of Advaita Vedanta. He was the founder of the Daśanāmi Sampradāya of Hindu monasticism and Ṣaṇmata of Smarta tradition. He introduced the Pañcāyatana form of worship.

Adi Shankara, along with Madhva and Ramanuja, was instrumental in the revival of Hinduism. These three teachers formed the doctrines that are followed by their respective sects even today. They have been the most important figures in the recent history of Hindu philosophy. In their writings and debates, they provided polemics against the non-Vedantic schools of Sankhya, Vaisheshika etc. Thus they paved the way for Vedanta to be the dominant and most widely followed tradition among the schools of Hindu philosophy. The Vedanta school stresses most on the Upanishads (which are themselves called Vedanta, End or culmination of the Vedas), unlike the other schools that gave importance to texts authored by their founders. The Vedanta schools have the belief that the Vedas, which include the Upanishads, are unauthored, forming a continuous tradition of wisdom transmitted orally. Thus the concept of apaurusheyatva ("being unauthored") came to be the guiding force behind the Vedanta schools. However, along with stressing the importance of Vedic tradition, Adi Shankara gave equal importance to the personal experience of the student. Logic, grammar, Mimamsa and allied subjects form main areas of study in all the Vedanta schools.

A well known verse, recited in the Smarta tradition, in praise of Adi Shankara is:

श्रुति स्मृति पुराणानामालयं करुणालयं|

नमामि भगवत्पादशंकरं लॊकशंकरं ||

Śruti smṛti purāṇānāṃālayaṃ karuṇālayaṃ|

Namāmi Bhagavatpādaśaṅkaraṃ lokaśaṅkaraṃ||

I salute the compassionate abode of the Vedas, Smritis and Puranas known as Shankara Bhagavatpada, who makes the world auspicious.

Works

Adi Shankara's works deal with logically establishing the doctrine of Advaita Vedanta as he saw it in the Upanishads. He formulates the doctrine of Advaita Vedanta by validating his arguments on the basis of quotations from the Vedas and other Hindu scriptures. He gives a high priority to svānubhava ("personal experience") of the student. His works are largely polemical in nature. He directs his polemics mostly against the Sankhya, Buddha, Jaina, Vaisheshika and other non-vedantic Hindu philosophies.

Traditionally, his works are classified under Bhāṣya ("commentary"), Prakaraṇa gratha ("philosophical treatise") and Stotra ("devotional hymn"). The commentaries serve to provide a consistent interpretation of the scriptural texts from the perspective of Advaita Vedanta. The philosophical treatises provide various methodologies to the student to understand the doctrine. The devotional hymns are rich in poetry and piety, serving to highlight the relationship between the devotee and the deity.

Adi Shankara wrote Bhashyas on the ten major Upanishads, the Brahma Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita. In his works, he quotes from Shveshvatara, Kaushitakai, Mahanarayana and Jabala Upanishads, among others. Bhashyas on Kaushitaki, Nrisimhatapani and Shveshvatara Upanishads are extant but the authenticity is doubtful. Adi Shankara's is the earliest extant commentary on the Brahma Sutras. However, he mentions older commentaries like those of Dravida, Bhartrprapancha and others.

In his Brahma Sutra Bhashya, Adi Shankara cites the examples of Dharmavyadha, Vidura and others, who were born with the knowledge of Brahman acquired in previous births. He mentions that the effects cannot be prevented from working on account of their present birth. He states that the knowledge that arises out of the study of the Vedas could be had through the Puranas and the Itihasas. In the Taittiriya Upanishad Bhashya 2.2, he says:

Sarveśāṃ cādhikāro vidyāyāṃ ca śreyah: kevalayā vidyāyā veti siddhaṃ

It has been established that everyone has the right to the knowledge (of Brahman) and that the supreme goal is attained by that knowledge alone.

Among the independent philosophical treatises, only Upadeśasāhasrī is accepted as authentic by modern academic scholars. Many other such texts exist, among which there is a difference of opinion among scholars on the authorship of Viveka Chudamani. The former pontiff of Sringeri Math, Shri Shri Chandrashekhara Bharati III has written a voluminous commentary on the Viveka Chudamani.

Adi Shankara begins his Gurustotram or Verses to the Guru with the following Sanskrit Sloka, that has become a widely sung Bhajan:

Guru Brahma, Guru Vishnu, Gurur Devo Maheshwara. Guru Sakshath Parambrahma, Tasmai Shri Gurave Namaha. (tr: Guru is Brahma, Guru is Vishnu, Guru is Siva. Guru is directly the supreme spirit — I offer my salutations to this Guru.)

Film

In 1983 a film named Adi Shankaracharya was premiered , the first film ever made entirely in Sanskrit, directed by G. V. Iyer.,