Amtrak

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Railway transport

| Amtrak | |

|---|---|

| |

|

| Reporting marks | AMTK, AMTZ |

| Locale | Continental United States, as well as Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal |

| Dates of operation | 1971–present |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8½ in (1,435 mm) ( standard gauge) |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

The National Railroad Passenger Corporation, doing business as Amtrak ( AAR reporting marks AMTK and AMTZ), is a government-owned corporation that was organized on May 1, 1971, to provide intercity passenger train service in the United States. "Amtrak" is a portmanteau of the words "American" and "track".

All of Amtrak's preferred stock is owned by the U.S. federal government. The members of its board of directors are appointed by the President of the United States and are subject to confirmation by the United States Senate. Common stock was issued in 1971 to railroads that contributed capital and equipment; its current holders consider the stock to be worthless but declined a 2002 buy-out offer by Amtrak.

Amtrak employs nearly 19,000 people. It operates passenger service on 21,000 miles of track primarily owned by other railroads connecting 500 destinations in 46 states. Some routes serve Canada. In fiscal year 2006, Amtrak served 24.3 million passengers, a company record. According to estimates for fiscal year 2007, Amtrak has served over the 25 million passenger mark, a 6% increase from the previous year.

History

Amtrak's origins are traceable to the sustained decline of private passenger rail services in the United States from about 1920 to 1970. In 1971, in response to the decline, Congress and the President created Amtrak. For its entire existence, the company has been subjected to political cross-winds and insufficiencies of capital resources and owned railway. Recent years have been among Amtrak's brightest; the corporation completed a significant rail project in the northeast in the early 2000s while its major competitors — particularly airlines — were affected by bankruptcies and rising fuel costs.

Passenger rail service before Amtrak

From the middle 1800's until approximately 1920, nearly all intercity travelers in the United States moved by rail. By 1910, close to 100 per cent of intercity passenger trips were by railroad. The rails and the trains were owned and operated by private, for-profit organizations. Approximately 65,000 railroad passenger cars operated in 1929.

For a long time after 1920, passenger rail's popularity diminished and there were a series of pullbacks and tentative recoveries. Rail passenger revenues declined dramatically between 1920 and 1934, but in the mid-1930s, railroads reignited popular imagination with service improvements and new, diesel-powered streamliners, such as the gleaming silver Pioneer Zephyr and Flying Yankee. Even with the improvements, on a relative basis, traffic continued to erode and by 1940 railroads held 67 per cent of passenger-miles in the United States. World War II broke the malaise. During the war, troop movements and restrictions on automobile fuel generated a sixfold increase in passenger traffic from the low point of the Depression. After the war, railroads rejuvenated overworked and neglected fleets with fast and often luxurious streamliners — epitomized by the Super Chief and California Zephyr — which inspired the last major resurgence in passenger rail travel. In 1948, Santa Fe CEO Fred Gurley reported a "complete reversal of our passenger traffic picture", with 1947 revenues exceeding those of 1936 by 220%.

The postwar resurgence was short-lived. In 1946, there remained 45 per cent fewer passenger trains than in 1929, and the decline quickened despite railroad optimism. Passengers disappeared and so did trains. Between 1946 and 1964, the annual number of passengers declined from 770 to 298 million. The number of U.S. commuter trains declined by more than 80 per cent, from more than 2,500 in 1954 to fewer than 500 in 1969. Few trains generated profits; most produced losses. Broad-based passenger rail deficits appeared as early as 1948 and by the mid-1950s railroads claimed aggregate annual losses on passenger services of more than $700 million (almost $5 billion in 2005 dollars using CPI). By 1965, only 10,000 rail passenger cars were in operation, 85% fewer than in 1929. Passenger service was provided on only 75,000 miles of track, a stark decline. Passenger rail service in the United States showed the signs of underinvestment. Rail facilities suffered from decrepit equipment, cavernous and nearly empty stations in dangerous urban centers, and management that seemed intent on driving away the few remaining customers. The 1960s also saw the end of railway post office revenues, which had helped some of the remaining trains break even.

Causes of decline of passenger rail

Literature suggests that the causes of the decline of passenger rail were complex. The industry was hobbled by government regulation and labor inflexibility, which undermined passenger rail just as the industry faced an explosion of competition from flexible and subsidized automobile and airplane transportation. These for-profit railroads were structured to sell access to elaborate, efficient roads at a profit; they lost in the competition for passengers to parallel, publicly-funded, non-profit turnpikes, air strips, and highways in the sky.

Government regulation and labor issues

The first interruption in passenger rail's vibrancy coincided with government intervention. From approximately 1910 to 1921, the Federal government introduced a populist rate-setting scheme, followed by nationalization of the rail industry for World War I. Ample railroad profits were erased, growth of the rail system was reversed, and railroads massively underinvested in passenger rail facilities during this time. Meanwhile, labor costs advanced, and with them passenger fares, which discouraged passenger traffic just as automobiles gained a foothold.

The primary regulatory authority affecting rail interest from early twentieth century was the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). The ICC played a leading role in rate-setting and intervened in other ways detrimental to passenger rail. In 1947, the ICC ruled that passenger trains could not exceed 79 mph (127 km/h) without in-cab signaling systems; the systems were criticized as being unnecessary and prohibitively expensive; after the regulation, plans to develop intercity high-speed rail services were shelved. In 1958, the ICC was granted authority to allow or reject modifications and eliminations of passenger routes (train-offs). Many routes required beneficial pruning, but the ICC delayed action by an average of eight months and when it did authorize modifications, the ICC insisted that unsuccessful routes be merged with profitable ones. Thus, fast, popular rail service was transformed into slow, unpopular service. The ICC was even more critical of corporate mergers. Many combinations, which railroads sought to compete, were delayed for years and even decades, such as the merger of the New York Central Railroad and Pennsylvania Railroad, into what eventually became Penn Central, and the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad and Erie Railroad into the Erie Lackawanna Railway. By the time the ICC approved the mergers in the 1960s, disinvestments by the federal government, years of deteriorating equipment and station facilities and the flight of passengers to the air and car had taken their toll and the mergers were unsuccessful.

At the same time, railroads carried a substantial tax burden. A World War II-era excise tax of 15% on passenger rail travel survived until 1962. Local governments, far from providing needed support to passenger rail, viewed rail infrastructure as a ready source for property tax revenues. In one extreme example, in 1959 the Great Northern Railroad, which owned about a third of one percent (.34%) of the land in Lincoln County, Montana, was assessed more than 91% of all school taxes in the county.

Railroads also were saddled with antiquated work rules and an inflexible relationship with trade unions. Work policies did not adapt to technological change. Average train speeds doubled from 1919 to 1959, but unions resisted efforts to modify their existing 100 to 150 mile work days. As a result, railroaders' work days were roughly cut in half, from 5 to 7½ hours in 1919, down to 2½ to 3¾ hours in 1959. Labor rules also perpetuated positions that had been obviated by technology. Between 1947 and 1957, passenger railroad financial efficiency dropped by 42% per mile.

Subsidized competition

While passenger rail faced internal and governmental pressures, new challenges appeared that undermined the dominance of passenger rail: highways and commercial aviation. The passenger rail industry wilted as government backed these potent upstarts with billions of dollars in construction.

Beginning roughly in the WWI era, cars became more attainable to most Americans. This newfound freedom and individualization of transit became the norm for most Americans because of the increased convenience. Government actively began to respond with funds from its treasury and later with fuel tax funds to build a non-profit network of roads not subject to property taxation that rivaled and then surpassed the for-profit network that the railroads had built in previous generations with corporate capital and government land grants. All told between 1921 and 1955 governmental entities, using taxpayer money and in response to taxpayer demand, financed more than $93 billion worth of pavement, construction, and maintenance.

In the 1950s, a second and more formidable threat appeared: affordable commercial aviation. Government at many levels supported aviation. Governmental entities built sprawling urban and suburban airports, and funded construction of highways to provide access to the airports.

Rail Passenger Service Act

In the late 1960s, the end of passenger rail in the United States seemed near. First had come the requests for termination of services; now came the bankruptcy filings. The legendary Pullman Company became insolvent 1969, followed by the dominant railroad in the Northeastern United States, the Penn Central, in 1970. It now seemed that passenger rail's financial problems might bring down the railroad industry as a whole. Few in government wanted to be held responsible for the extinction of the passenger train, but another solution was necessary.

In 1970, Congress passed and, in a surprise, President Richard Nixon signed into law, the Rail Passenger Service Act. Proponents of the bill, led by the National Association of Railroad Passengers (NARP), sought government funding to assure the continuation of passenger trains. They conceived the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (NRPC), a hybrid public-private entity that would receive taxpayer funding and assume operation of intercity passenger trains. The original working brand name for NRPC was Railpax, but shortly before the company started operating it was changed to Amtrak. There were several key provisions:

- Any railroad operating intercity passenger service could contract with the NRPC, thereby joining the national system.

- Participating railroads bought into the NRPC using a formula based on their recent intercity passenger losses. The purchase price could be satisfied either by cash or rolling stock; in exchange, the railroads received NRPC common stock.

- Any participating railroad was freed of the obligation to operate intercity passenger service after May 1, 1971, except for those services chosen by the Department of Transportation as part of a "basic system" of service and paid for by NRPC using its federal funds.

- Railroads that chose not to join the NRPC system were required to continue operating their existing passenger service until 1975 and thenceforth had to pursue the customary Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) approval process for any discontinuance or alteration to the service.

Nearly everyone involved expected the experiment to be short-lived. The Nixon administration and many Washington insiders viewed the NRPC as a politically expedient way for the President and Congress to give passenger trains the one "last hurrah" demanded by the public. They expected Amtrak to quietly disappear as public interest waned. Proponents also hoped that government intervention would be brief, but their view was that Amtrak would soon support itself. Neither view has yet proved correct. Popular support has allowed Amtrak to continue in operation longer than critics imagined while financial results have made infeasible a return to private operation.

Early days

Amtrak began operations May 1, 1971. The corporation was molded from the passenger rail operations of 20 out of 26 major railroads in operation at the time. The railroads contributed rolling stock, equipment, and capital. In return, they received approval to discontinue their passenger services, and at least some acquired common stock in Amtrak. Amtrak received no rail tracks or right-of-way at its inception. Railroads that shed passenger operations were expected to host Amtrak trains on their tracks, for a fee.

There was a period of adjustment. All Amtrak's routes were continuations of prior service, although Amtrak pruned about half the passenger rail network. Of the 364 trains operated previously, Amtrak only continued 182. On trains that continued, to the extent possible, schedules were retained with only minor changes from the Official Guide of the Railways. Former names largely were continued.

Several major corridors became freight-only, including New York Central Railroad's Water Level Route across New York and Ohio and Grand Trunk Western Railroad's Chicago to Detroit service, although service soon returned to the Water Level Route with introduction of the Lake Shore Limited. Reduced passenger train schedules created headaches. A 19-hour layover became necessary for eastbound travel on the James Whitcomb Riley between Chicago and Newport News.

Amtrak inherited problems with stations, most notably deferred maintenance, and redundant facilities resulting from competing companies that served the same areas. On the day it started, Amtrak was given the responsibility of rerouting passenger trains from the seven train terminals in Chicago (LaSalle, Dearborn, Grand Central, Randolph, Chicago Northwestern Terminal, Central, and Union) into just one, Union Station. In New York Amtrak had to pay to maintain Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal because of the lack of track connections to bring trains from upstate New York into Penn Station, a problem not rectified until the building of the Empire Connection in 1991. In many cases Amtrak had to abandon service into the huge old Union Stations such as Cincinnati, Saint Paul, Buffalo, Kansas City, and Saint Louis and route trains into smaller Amtrak-built facilities down the line (although Amtrak has pushed to start reusing some of the old stations, most recently Cincinnati Union Terminal, and Kansas City Union Station).

On the other hand, merged operations presented efficiencies such as the combination of three West Coast trains into the Coast Starlight, running from San Diego to Seattle. The Northeast Corridor received an Inland Route via Springfield, Massachusetts, thanks to support from New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts. The North Coast Hiawatha was implemented as a second Pacific Northwest route. The Milwaukee to St. Louis Abraham Lincoln and Prairie State routes also commenced. The first all-new Amtrak route, not counting the Coast Starlight, was the Vermonter/ Washingtonian. That route was inaugurated September 29, 1972, along Boston and Maine Railroad and Canadian National Railway track that had last seen passenger service in 1966.

Amtrak soon had the opportunity to acquire railway. Following the bankruptcy of several northeastern railroads in the early 1970s, including Penn Central which owned and operated the Northeast Corridor, Congress passed the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976. A large part was directed to the creation of a Conrail, but in addition the law enabled transfer to Amtrak of the Northeast Corridor railway from Boston, Massachusetts to Washington, D.C. That track became Amtrak's jewel. In subsequent years, short route segments not needed for freight operations were transferred to Amtrak. Nevertheless, in general, Amtrak remained dependent on freight railroads for access to most of its routes.

Amtrak fell far short of financial independence in its first decade, but it did find modest success rebuilding trade. Outside factors discouraged competing transport, such as fuel shortages which increased costs of automobile and airline travel, and strikes which disrupted airline operations. Investments in Amtrak's track, equipment and information also made Amtrak more relevant to America's transportation needs. Amtrak's ridership increased from 16.6 million in 1972 to 21 million in 1981.

Leaders and political influences

Unlike many large businesses, subsequent to its formation Amtrak has had only one active investor: the U.S. government. Like most investors, the Federal government has demanded a degree of accountability. Determination of congressional funding and selection of Amtrak's leadership have been infused with political considerations. As discussed below, funding levels and capital support have varied over time.

Some members of Amtrak's board and executive leadership have had little or no experience with railroads. Conversely, Amtrak also has benefited from the interest of highly motivated and politically-oriented public servants. For example, in 1982, former Secretary of the Navy and retired Southern Railway head W. Graham Claytor Jr., brought his naval and railroad experience to the job. Claytor had served briefly as an acting Secretary of Transportation in the cabinet of President Jimmy Carter in 1979, and came out of retirement to lead Amtrak after the disastrous financial results during the Carter administration (1977-1981). He was recruited and strongly supported by John H. Riley, an attorney who was the highly skilled head of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) under the Reagan Administration from 1983-1989. Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole also tacitly supported Amtrak. Claytor seemed to enjoy a good relationship with the Congress and was perceived to have done a good job, albeit through extensive use of short-term debt.

In the 1990s, Claytor was succeeded at Amtrak's helm by a succession of career public servants. First, Thomas Downs, who had overseen the Union Station project in Washington, DC, which experienced substantial delays and cost overruns, assumed the leadership. In January, 1998, after Amtrak weathered a serious cash shortfall, George Warrington succeeded Downs. Warrington previously led Amtrak's Northeast Corridor Business Unit.

Then in April, 2002, David L. Gunn was selected as president. Gunn had a strong reputation as a straightforward and experienced manager. He was not one to shy away from conflict with others. Years earlier (between 1991 and 1994), Gunn's refusal to "do politics" put him at odds with the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority board of directors, which included representatives from the District of Columbia and suburban jurisdictions in Maryland and Virginia. Gunn was an accomplished public servant and railroad person and his successes before Amtrak earned him a great deal of credibility, despite a sometimes-rough relationship with politicians and labor unions.

Gunn was polite but direct in response to congressional criticism of Amtrak, and his tenure was punctuated by successes in reducing layers of management overhead in Amtrak and streamlining operations. Amtrak's Board of Directors removed Gunn on November 9, 2005; he was succeeded by David Hughes, Amtrak's Chief Engineer. Given Gunn's solid performance, many Amtrak supporters feared that Gunn's departure was Amtrak's death knell, although those fears have not been realized. On August 29, 2006, Alexander Kummant was named as Gunn's permanent replacement effective September 12, 2006.

The list of Presidents of Amtrak includes:

- Roger Lewis 1971-.

- Paul Reistrup.

- Alan Stephenson Boyd -1982.

- W. Graham Claytor Jr. 1982-1993.

- Thomas Downs 1993-1998.

- George Warrington 1998-2002.

- David L. Gunn 2002-2005.

- David Hughes (interim) 2005-2006.

- Alexander Kummant 2006-present.

Modern history (1980s to present)

Ridership stagnated at roughly 20 million passengers per year amid uncertain government aid from 1981 to about 2000. Ridership increased in the 2000s after implementation of capital improvements in the Northeast Corridor and rises in automobile fuel costs. Since 2002, Amtrak has had four consecutive years of record ridership. During fiscal year 2006, Amtrak reported more than 24.3 million passengers, its highest total to date. According to Amtrak, an average of more than 70,000 passengers ride on up to 300 Amtrak trains per day.

In the 1990s, Amtrak's stated goal remained operational self-sufficiency. By this time, however, Amtrak had a large overhang of debt from years of underfunding, and in the mid-1990s, Amtrak suffered through a serious cash crunch. To resolve the crisis, Congress issued funding but instituted a glide-path to financial self-sufficiency, excluding railroad retirement tax act payments. Passengers became "guests" and there were expansions into express freight work, but the financial plans failed. Amtrak's inroads in express freight delivery created additional friction with competing freight operators, including the trucking industry. Delivery was delayed of much anticipated high-speed trainsets for the improved Acela Express service, which promised to be a strong source of income and favorable publicity along the Northeast Corridor between Boston and Washington DC. Through the late 1990s and early 2000s, Amtrak could not add sufficient express revenue or cut sufficient other services to break even. By 2002 it was clear that Amtrak could not achieve self-sufficiency, but Congress continued to authorize funding and released Amtrak from the requirement.

Amtrak's leader at the time, David L. Gunn, was polite but direct in response to congressional criticism. In a departure from his predecessors' promises to make Amtrak self-sufficient in the short term, Gunn argued that no form of passenger transportation in the United States is self-sufficient as the economy is currently structured. Highways, airports, and air traffic control all require large government expenditures to build and operate, coming from the Highway Trust Fund and Aviation Trust Fund paid for by user fees, highway fuel and road taxes, and, in the case of the General Fund, by people who own cars and do not.

Before a congressional hearing, Gunn answered a demand by leading Amtrak critic Arizona Senator John McCain to eliminate all operating subsidies by asking the Senator if he would also demand the same of the commuter airlines, upon whom the citizens of Arizona are dependent. McCain, usually not at a loss for words when debating Amtrak funding, did not reply.

Under Gunn, almost all the controversial express business was eliminated. The practice of tolerating deferred maintenance was reversed to eliminate a safety issue. The policies improved labor relations to some extent, even as Amtrak's ranks of unionized and salaried workers thinned.

Amtrak's current chief, Alexander Kummant, is committed to operating a national rail network, and he does not envision separating the Northeast corridor (the segment from Boston to Richmond) under separate ownership. He has said that shedding the system's long distance routes would amount to selling national assets that are on par with national parks, and that Amtrak's abandonment of these routes would be irreversible. Amtrak is seeking annual congressional funding of $1 billion for ten years. Kummant has stated that the investment is moderate in light of Federal investment in other modes of transportation.

Public funding

Amtrak commenced operations in 1971 with $40 million in direct Federal aid, $100 million in Federally insured loans, and a somewhat larger private contribution. Officials expected that Amtrak would break even by 1974, but those expectations proved unrealistic and annual direct Federal aid reached a 17-year high in 1981 of $1.25 billion. During the Reagan administration, appropriations were halved. By 1986, Federal support fell to a decade low of $601 million, almost none of which were capital appropriations. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Congress continued the reductionist trend even while Amtrak expenses held steady or rose. Amtrak was forced to borrow to meet short-term operating needs, and by 1995 Amtrak was on the brink of a cash crisis and was unable to continue to service its debts. In response, in 1997 Congress authorized $5.2 billion for Amtrak over the next five years — largely to complete the Acela capital project — on the condition that Amtrak submit to the ultimatum of self-sufficiency by 2003 or liquidation. Amtrak made financial improvements during the period, but ultimately did not achieve self sufficiency.

In the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, during which Amtrak kept running while airlines were grounded, the value of a national passenger rail service was briefly acknowledged in Washington. But when Congress returned to work following the attacks, the airlines received a $15 billion bailout package, and inattention toward Amtrak resumed.

In 2004, a stalemate in Federal support of Amtrak forced cutbacks in services and routes as well as resumption of deferred maintenance. In fiscal 2004 and 2005, Congress appropriated about $1.2 billion for Amtrak, $300 million more than President George W. Bush had requested. However, the company's board requested $1.8 billion through fiscal 2006, the majority of which (about $1.3 billion) would be used to bring infrastructure, rolling stock, and motive power back to a state of good repair. In Congressional testimony, the Department of Transportation's inspector-general confirmed that Amtrak would need at least $1.4 billion to $1.5 billion in fiscal 2006 and $2 billion in fiscal 2007 just to maintain the status quo. In 2006, Amtrak received just under $1.4 billion, with the condition that Amtrak would reduce (but not eliminate) food and sleeper service losses. Thus, dining service were simplified and now require two fewer on-board service workers. Only Auto Train and Empire Builder services continue regular made onboard meal service.

State governments have partially filled the breach left by reductions in Federal aid. Several states have entered into operating partnerships with Amtrak, notably California, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Michigan, Oregon, Missouri, Washington, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, Vermont, Maine, and New York, as well as the Canadian province of British Columbia, which provides some of the resources for the operation of the Cascades route.

With the dramatic rise in gasoline prices during 2007-2008, Amtrak has seen record ridership. Capping a steady five year increase in ridership overall, regional lines saw 12% year-over-year growth in May, 2008. In October, 2007, the Senate passed S-294, "Passenger Rail Improvement and Investment Act of 2007" (70-22) sponsored by Senators Frank Lautenberg and Trent Lott. Despite a veto threat by President Bush, a similar bill passed the House on June 11, 2008 with a veto-proof margin (311-104).

Controversy

Aid to Amtrak by government was controversial from the beginning. Formation of Amtrak in 1971 was criticized as a bailout serving corporate rail interests and union railroaders, not the traveling public. Critics assert that Amtrak has proven incapable of operating as a business and does not provide valuable transportation services meriting public support, a "mobile money-burning machine." They argue that subsidies should be ended, national rail service terminated, and the Northeast Corridor turned over to private interests. "To fund a Nostalgia Limited is not in the public interest." Critics also question Amtrak's energy efficiency. The U.S. Department of Energy considers Amtrak among the most energy-efficient forms of transportation.

Proponents point out that the government heavily subsidizes the Interstate Highway System and many aspects of passenger aviation. Massive government aid of those forms of travel was a primary factor in the decline of passenger service on privately owned railroads in the 1950s and 60s. Meanwhile, Amtrak, through fees to host railroads, pays property taxes that highway users do not pay. Advocates therefore assert that Amtrak should only be expected to be as self-sufficient as those competing modes.

In a June 12, 2008 interview with Reuters, current Amtrak President Alex Kummant made specific observations: $10 billion per year is transferred from the general fund to the Highway Trust Fund; $2.7 billion is granted to the FAA; $8 billion goes to "security and life safety for cruise ships." Overall, Kummant claims that Amtrak receives $40 in federal funds per passenger, while highways are subsidized at a rate of $500-$700 per automobile. Moreover, Amtrak provides all of its own security, while airport security is a separate federal subsidy. Kummant added: "Let's not even get into airport construction which is a miasma of state, federal and local tax breaks and tax refinancing and God knows what."

Critics claim that gasoline taxes amount to use fees that entirely pay for the government subsidies to the highway system and aviation. In fact this is not true: gas taxes cover little if any of the costs for "local" highways and in many states little of the cost for state highways. They don't cover the property taxes foregone by building tax-exempt roads. They also don't cover policing costs: Amtrak, like all U.S. railroads, pays for its own security, the Amtrak Police; road policing and the Transportation Security Administration are paid for out of general taxation.

Labor issues

Intractable positions staked out by labor leaders were blamed for part of the decline of passenger rail service in the early to middle 20th century, and labor union clout was widely credited with facilitating the creation of Amtrak in 1971. Many trade union jobs were saved by the bailout.

In recent times, efforts at reforming passenger rail have addressed labor issues. In 1997 Congress released Amtrak from a prohibition on contracting for labor outside of the corporation (and outside its unions), opening the door to privatization. Since that time, many of Amtrak's employees have been working without a contract. The most recent contract, signed in 1999, was mainly retroactive.

Still, though, the influence of unions is a strong force against change. Amtrak has 14 separate unions to negotiate with, because of the fragmentation of railroad unions by job. And it has 24 separate contracts with those unions. This makes it difficult to make substantial changes, in contrast to a situation where one union negotiates with one employer. Current Amtrak president Kummant seems poised to follow a cooperative posture with Amtrak's trade unions. He has ruled out plans to privatize large parts of Amtrak's unionized workforce.

In late 2007 and early 2008, however, major labor issues came up, a result of a dispute between Amtrak and 16 unions over healthcare, specifically to which employees healthcare should be available to. The dispute was not resolved quickly, and the situation escalated, to the point of President Bush declaring a Presidential Emergency Board to resolve the issues. It was not immediately successful, and a strike was threatened, to begin on January 30th, 2008. In the middle of that month, however, it was announced that Amtrak and the unions had come to terms and January 30th passed without a strike. In late February it was announced that three more unions had worked out their differences, and as of that time it seems unlikely that any more issues will arise in the near future.

Amtrak operations and services

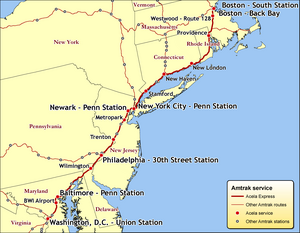

Amtrak is no longer required by law, but is encouraged, to operate a national route system. Amtrak has some presence in all of the 48 contiguous states except Wyoming and South Dakota. Service on the Northeast Corridor, between Boston, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C., as well as between Philadelphia and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, is powered by overhead wires; for the rest of the system, diesel locomotives are used. Routes vary widely in frequency of service, from three trips weekly on the Sunset Limited, from Los Angeles, California, to New Orleans, Louisiana, to weekday service several times per hour on the Northeast Corridor, from New York City to Washington, D.C. Amtrak also operates a captive bus service, Thruway Motorcoach, which provides connections to train routes.

The most-popular and heavily used routes are those on the Northeast Corridor, which include the Acela Express, and Regional. Those routes serve Boston, Massachusetts; New York City; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Washington, D.C.; and many communities between. Four of the six stations busiest by boardings are on the corridor: New York (Penn Station) (first), Washington (Union Station) (second), Philadelphia (30th Street Station) (third), and Boston (South Station) (sixth). The other two of the top six are Chicago (Union Station) (fourth) and Los Angeles (Union Station) (fifth).

Amtrak trains have both names and numbers. Train routes are named to reflect the rich and complex history of the routes and the areas traversed by them. Each scheduled run of the route is assigned a number. Generally, even-numbered routes run northward and eastward, while odd-numbered routes run southward and westward. Some routes, such as the Pacific Surfliners, use the opposite numbering system, inherited from the previous operators of similar routes, such as the Santa Fe Railroad.

Some of the trains used more often:

|

West Coast

|

Rail passenger efficiency versus other modes

Per passenger mile, Amtrak is 18 percent more energy-efficient than commercial airlines and automobiles, though the exact figures for particular routes depend on load factor along with other variables. Advanced technology further increases efficiency: regenerative braking on the Acela Express, for example, reduces electric-energy consumption by 8 percent. Passenger rail is also competitive with other modes in terms of safety per mile.

| Mode | Revenue per passenger mile | Energy consumption per passenger mile | Deaths per 100 million passenger miles | Reliability |

| Domestic airlines | 12.0¢ | 3,182 BTUs | 0.02 deaths | 82% |

| Intercity buses | 12.9¢ | 3,393 BTUs | 0.05 deaths | N |

| Amtrak | 26.0¢ | 2,100 BTUs | 0.03 deaths | 74% |

| Autos | N/A | 3,458 BTUs | 0.80 deaths | N/A |

Intermodal connections

Intermodal connections between Amtrak trains and other transportation are available at many stations. Most Amtrak rail stations in downtown areas have connections to local public transport. Amtrak also code shares with Continental Airlines, providing service between Newark Liberty International Airport (via its Amtrak station and AirTrain Newark) and Philadelphia 30th St, Wilmington, Stamford, and New Haven. Amtrak also serves airport stations at Milwaukee, Oakland, Burbank, and Baltimore.

Amtrak coordinates Thruway Motorcoach service to extend many of its routes, especially in California.

Gaps in service

Outside the Northeast Corridor, Amtrak is a niche player in passenger transportation. In 2003, Amtrak accounted for just 0.1% of U.S. intercity passenger miles (5,680,000,000 out of 5,280,860,000,000 total, of which private-automobile travel makes up the vast majority). In fiscal year 2004, Amtrak routes served over 25 million passengers, while, in calendar year 2004, commercial airlines served over 712 million passengers.

Amtrak provides some rail service in 46 states. The only states that are not served by Amtrak are Hawaii (in the middle of the Pacific Ocean), Alaska (served by the Alaska Railroad), and South Dakota (although in years past there was service by the Milwaukee Road to South Dakota, Amtrak has never instituted any service to that state) and Wyoming (lost rail service in the 1997 cuts, and in early 2008 lost the Denver-Casper motorcoach service). Amtrak serves many states only nominally through stations along borders and/or away from major population areas. Many major cities in the Midwest, West, and South have two or fewer trains per day, such as Atlanta, Denver, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, and Minneapolis–Saint Paul.

Amtrak's reliance on freight railroads also has caused its service elimination. Passenger rail service was entirely discontinued to Phoenix, Arizona, in 1997, after the Union Pacific Railroad, which owns the tracks that served Phoenix, announced that it was abandoning the right of way. Amtrak did not have the funds to maintain the trackage. Today, the city is served only by Thruway Motorcoach. In 1983, the Palmetto was truncated from St. Petersburg to Tampa, Florida because Amtrak was unable to take on the costs of maintaining the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad drawbridge, which took the train over Tampa Bay.

Damage to railroad track caused by Hurricane Katrina interrupted service on the Sunset Limited. Originally the train departed from Orlando, Florida, but the track damage along the Gulf coast caused the train to originate at New Orleans, Louisiana. Although the track's owner, CSX, completed repairs by early 2006, Amtrak service has not resumed over two years later, leaving the intermediate stations between Jacksonville, Florida and New Orleans without any Amtrak service.

Several significant Amtrak routes have been eliminated because of lack of funding since 1971, creating other gaps. The east–west train feeding Kansas City, Missouri, with New York and Washington, D.C., called the National Limited, was cut, leaving Chicago as the only throughway for direct links between the Midwest and East. The North Coast Hiawatha, between Chicago and Seattle, provided only reduced service between Chicago and the Pacific Northwest. The last link with the vaunted Chicago–Florida services of such trains as the City of Miami, the Dixie Flagler, and the South Wind, was broken when the Floridian was discontinued, in October 1979. In 1997, the Desert Wind and Pioneer were discontinued, along with service to Las Vegas, Boise, and all of Wyoming. In 2003, Amtrak discontinued the Kentucky Cardinal, ending all service to Louisville. In 2005, Three Rivers (a reborn Broadway Limited) was nixed, removing the only direct New York–Chicago service through central Pennsylvania.

Guest Rewards

Amtrak's loyalty program, Guest Rewards, is similar to the frequent-flyer programs of many airlines. Guest Rewards members accumulate points by riding Amtrak and through other activities, and can redeem these points for free or discounted Amtrak tickets and other rewards.

Freight

Amtrak Express provides small-package and less-than-truckload shipping among more than 100 cities. Amtrak Express also offers station-to-station shipment of human remains to many express cities. At smaller stations, funeral directors must load and unload the shipment onto and off the train. Amtrak hauled mail for the United States Postal Service and time-sensitive freight, but discontinued these services in October 2004. On most parts of the few lines that Amtrak owns, trackage-rights agreements allow freight railroads to use its trackage.

Commuter services

Through various commuter services, Amtrak serves an additional 61.1 million passengers per year in conjunction with state and regional authorities in California, Connecticut, Maryland, Virginia, and Washington. Amtrak's Capitol Corridor, Pacific Surfliner (formerly San Diegan), and San Joaquins are funded mostly by a state transit authority, Caltrans, rather than the federal government.

Classes of Service

Amtrak has a variety of cabins that suit a variety of needs. Classes are similar to those used by airlines.

First Class service is offered on the Acela Express only. First Class passengers have access to Amtrak ClubAcela lounges in Washington DC, Philadelphia, New York and Boston (lounges offer complementary drinks, personal ticketing service, lounge seating, conference areas, computer/internet access and televisions tuned to CNN). At the Philadelphia and Washington DC ClubAcelas, passengers can board their train directly from the ClubAcela (In Philadelphia, passenger use an elevator while in Washington, passengers leave through a side door leading to the tracks). Seats are larger than those of Business Class and come in a variety of seating modes (single, single with table, double, double with table and wheelchair accessible). First Class is located in a separate car than the other classes and each train set contains only one First Class car. First Class includes complimentary meal and beverage service along with free newspapers and hot towel service. First Class seats are set in a 1x2 configuration. There are two attendants per car.

Business Class is the minimum class of service on the Acela Express and is offered as an upgrade on Regional and other short to long distance trains. Business Class seats are larger than those in coach. Business Class passengers have easy access to the cafe car. they also receive complementary non-alcoholic beverages and free newspapers. Business Class seats all have power outlets for electronics. Business Class seats are located in different areas depending on the train. On some trains, Business Class is located at the front of the Cafe Car. These seats are in a 1x2 style and feature leather upholstery, cup holders and leg rests. These seats also recline to a more "sofa recliner style". The other type of Business Class seat is located in an actual Business Class car. These seats are organized in a 2x2 style and feature more legroom than the coach seats in the other cars.

Coach Class is the minimum class of service on Amtrak trains and includes footrests and decent legroom. Coach seats are set in a 2x2 configuration.

Sleeper Service rooms are considered First Class on long distance trains. Rooms are classified into roomettes, bedrooms, family bedrooms and accessible bedrooms. With the price of a room comes complementary meals and attendant service. At night, rooms turn into sleeping areas with fold down beds and fresh linens. Complementary bottled water, newspapers and turn down service is included as well. Sleeper car passengers have access to the entire train. Sleeper passengers also have access to the Club Acela lounges in stations along the Northeast Corridor and access to the Metropolitan Lounges in Chicago, Miami, New Orleans, and Minneapolis/Saint Paul.

Trains and tracks

Most tracks on which Amtrak operates are owned by freight railroads. Amtrak operates over all seven Class I railroads in the United States, as well as several short lines: the Pan Am Railways, New England Central Railroad, and Vermont Railway. Other sections are owned by terminal railroads jointly controlled by freight companies or by commuter rail agencies. The arrangement has two notable impacts on Amtrak operations. The host railroad is responsible for maintenance and occasionally Amtrak has suffered service disruptions from untimely track rehabilitation. When host railroads have simply refused to maintain their tracks to Amtrak's needs, Amtrak occasionally has been compelled to pay the host to maintain the tracks. Also, Amtrak enjoys priority over the host's freight traffic only for a specified window of time. When a passenger train misses that window, host railroads may (and frequently do) direct passenger trains to follow lumbering freight traffic, severely exacerbating even minor delays.

Tracks owned by Amtrak

Along the Northeast Corridor and in several other areas, Amtrak owns 730 route-miles of track (1175 km), including 17 tunnels consisting of 29.7 miles of track (47.8 km), and 1,186 bridges (including the famous Hell Gate Bridge) consisting of 42.5 miles (68.4 km) of track. Amtrak owns and operates the following lines:

Northeast Corridor

The Northeast Corridor between Washington, D.C. and Boston via Baltimore, Philadelphia, Newark, New York and Providence, Rhode Island is largely owned by Amtrak, working cooperatively with several state and regional commuter agencies. Amtrak's portion was acquired in 1976 as a result of the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act.

- Boston to the Massachusetts/Rhode Island state line (operated and maintained by Amtrak but owned by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts)

- 118.3 miles (190.4 km), Massachusetts/Rhode Island state line to New Haven, Connecticut

- 240 miles (386 km), New Rochelle, New York to Washington, D.C.

The part of the line from New Haven to the New York/Connecticut border ( Port Chester/ Greenwich) is owned by the state of Connecticut, while the portion from Port Chester to New Rochelle is owned by the state of New York. The Connecticut Department of Transportation and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority operate this line through Metro-North Railroad.

Philadelphia to Harrisburg Main Line

This line runs from Philadelphia to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. As a result of an investment partnership with the commonwealth of Pennsylvania, signal and track improvements were completed in October 2006, and now allow all-electric service with a top speed of 110 mph (about 175 km/h) to run along the corridor.

- 104 miles (167 km), Philadelphia to Harrisburg ( Pennsylvanian and Keystone Service)

Empire Corridor

- 11 miles (18 km), New York Penn Station to Spuyten Duyvil, New York

- 35.9 miles (57.8 km), Stuyvesant to Schenectady, New York (operated and maintained by Amtrak, but owned by CSX)

- 8.5 miles (13.8 km), Schenectady to Hoffmans, New York

New Haven-Springfield Line

- 60.5 mi (97.4 km), New Haven to Springfield ( Regional and Vermonter)

Other tracks

- Chicago-Detroit Line - 98 miles (158 km), Porter, Indiana to Kalamazoo, Michigan ( Wolverine)

- Post Road Branch - 12.42 miles (20 km), Post Road Junction to Rensselaer, New York ( Lake Shore Limited)

Amtrak also owns station and yard tracks in Chicago; Hialeah (near Miami, Florida) (leased from the State of Florida); Los Angeles; New Orleans; New York City; Oakland (Kirkham Street Yard); Orlando; Portland, Oregon; Saint Paul, Minnesota; Seattle; and Washington, D.C.

Amtrak owns the Chicago Union Station Company ( Chicago Union Station) and Penn Station Leasing ( New York Penn Station). It has a 99.7% interest in the Washington Terminal Company (tracks around Washington Union Station) and 99% of 30th Street Limited (Philadelphia 30th Street Station). Also owned by Amtrak is Passenger Railroad Insurance.

Other infrastructure:

|

|

|

|