Blood type

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Health and medicine

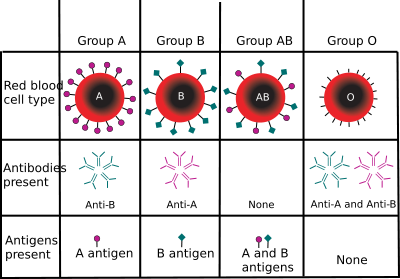

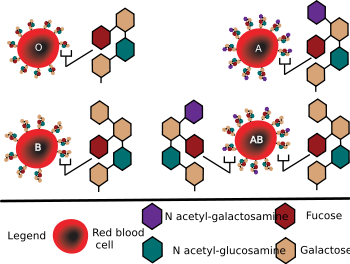

A blood type (also called a blood group) is a classification of blood based on the presence or absence of inherited antigenic substances on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). These antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycoproteins, or glycolipids, depending on the blood group system, and some of these antigens are also present on the surface of other types of cells of various tissues. Several of these red blood cell surface antigens, that stem from one allele (or very closely linked genes), collectively form a blood group system.

Blood types are inherited and represent contributions from both parents. A total of 29 human blood group systems are now recognized by the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT).

Many pregnant women carry a fetus with a different blood type from their own, and the mother can form antibodies against fetal RBCs. Sometimes these maternal antibodies are IgG, a small immunoglobulin, which can cross the placenta and cause hemolysis of fetal RBCs, which in turn can lead to hemolytic disease of the newborn, an illness of low fetal blood counts which can be temporary or treatable, but can occasionally be severe.

Serology

If an individual is exposed to a blood group antigen that is not recognised as self, the immune system will produce antibodies that can specifically bind to that particular blood group antigen, and an immunological memory against that antigen is formed. The individual will have become sensitized to that blood group antigen. These antibodies can bind to antigens on the surface of transfused red blood cells (or other tissue cells), often leading to destruction of the cells by recruitment of other components of the immune system. When IgM antibodies bind to the transfused cells, the transfused cells can clump. It is vital that compatible blood is selected for transfusions and that compatible tissue is selected for organ transplantation. Transfusion reactions involving minor antigens or weak antibodies may lead to minor problems. However, more serious incompatibilities can lead to a more vigorous immune response with massive RBC destruction, low blood pressure, and even death.

ABO and Rh blood grouping

Anti-A and Anti-B, the common IgM antibodies to the RBC surface antigens of the ABO blood group system are sometimes described as being "naturally occurring", however, this is a misnomer, because these antibodies are formed in infancy by sensitisation in the same way as other antibodies. The theory that explains how these antibodies are developed states that antigens similar to the A and B antigens occur in nature, including in food, plants and bacteria. After birth an infant gut becomes colonized with normal flora which express these A-like and B-like antigens, causing the immune system to make antibodies to those antigens that the red cells do not possess. So, people who are blood type A will have Anti-B, blood type B will have Anti-A, blood type O will have both Anti-A and Anti-B, and blood type AB will have neither. Because of these so called "naturally occurring" and expected antibodies, it is important to correctly determine a patient's blood type prior to transfusion of any blood component. These naturally occurring antibodies are of the IgM class, which have the capability of agglutinating (clumping) and damaging red cells within the blood vessels, possibly leading to death. It is not necessary to determine any other blood groups because almost all other red cell antibodies can only develop through active immunization, which can only occur through either previous blood transfusion or pregnancy. A test called the Antibody Screen is always performed on patients who may require red blood cell transfusion, and this test will detect most clinically significant red cell antibodies.

The RhD antigen is also important in determining a person's blood type. The terms "positive" or "negative" refer to either the presence or absence of the RhD antigen irrespective of the presence or absence of the other antigens of the Rhesus system. Anti-RhD is not usually a naturally occurring antibody as the Anti-A and Anti-B antibodies are. Cross-matching for the RhD antigen is extremely important, because the RhD antigen is immunogenic, meaning that a person who is RhD negative is very likely to make Anti-RhD when exposed to the RhD antigen (perhaps through either transfusion or pregnancy). Once an individual is sensitised to RhD antigens their blood will contain RhD IgG antibodies which can bind to RhD positive RBCs and may cross the placenta.

Blood group systems

A total of 29 human blood group systems are now recognized by the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT). A complete blood type would describe a full set of 29 substances on the surface of RBCs, and an individual's blood type is one of the many possible combinations of blood group antigens. Across the 29 blood groups, over 600 different blood group antigens have been found, but many of these are very rare or are mainly found in certain ethnic groups.

Almost always, an individual has the same blood group for life; but very rarely an individual's blood type changes through addition or suppression of an antigen in infection, malignancy or autoimmune disease. An example of this rare phenomenon is the case Demi-Lee Brennan, an Australian citizen, whose blood group changed after a liver transplant. Another more common cause in blood type change is a bone marrow transplant. Bone marrow transplants are performed for many leukemias and lymphomas, among other diseases. If a person receives a bone marrow from someone who is a different ABO type (ex. a type A patient receives a type O bone marrow), the patient's blood type will eventually convert to the donor's type.

Some blood types are associated with inheritance of other diseases; for example, the Kell antigen is sometimes associated with McLeod syndrome. Certain blood types may affect susceptibility to infections, an example being the resistance to specific malaria species seen in individuals lacking the Duffy antigen. The Duffy antigen, presumably as a result of natural selection, is less common in ethnic groups from areas with a high incidence of malaria.

ABO blood group system

The ABO system is the most important blood group system in human blood transfusion. The associated anti-A antibodies and anti-B antibodies are usually " Immunoglobulin M", abbreviated IgM, antibodies. ABO IgM antibodies are produced in the first years of life by sensitization to environmental substances such as food, bacteria and viruses. The "O" in ABO is often called "0" (zero/null) in other languages.

| Phenotype | Genotype |

|---|---|

| A | AA or AO |

| B | BB or BO |

| AB | AB |

| O | OO |

Rhesus blood group system

The Rhesus system is the second most significant blood group system in human blood transfusion. The most significant Rhesus antigen is the RhD antigen because it is the most immunogenic of the five main rhesus antigens. It is common for RhD negative individuals not to have any anti-RhD IgG or IgM antibodies, because anti-RhD antibodies are not usually produced by sensitization against environmental substances. However, RhD negative individuals can produce IgG anti-RhD antibodies following a sensitizing event: possibly a fetomaternal transfusion of blood from a fetus in pregnancy or occasionally a blood transfusion with RhD positive RBCs.

ABO and Rh distribution by country

| Country | O+ | A+ | B+ | AB+ | O− | A− | B− | AB− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 30% | 33% | 12% | 6% | 7% | 8% | 3% | 1% |

| Australia | 40% | 31% | 8% | 2% | 9% | 7% | 2% | 1% |

| Belgium | 38.1% | 34% | 8.5% | 4.1% | 7% | 6% | 1.5% | 0.8% |

| Canada | 39% | 36% | 7.6% | 2.5% | 7% | 6% | 1.4% | 0.5% |

| Denmark | 35% | 37% | 8% | 4% | 6% | 7% | 2% | 1% |

| Finland | 27% | 38% | 15% | 7% | 4% | 6% | 2% | 1% |

| France | 36% | 37% | 9% | 3% | 6% | 7% | 1% | 1% |

| Germany | 35% | 37% | 9% | 4% | 6% | 6% | 2% | 1% |

| Hong Kong, China | 40% | 26% | 27% | 7% | <0.3% | <0.3% | <0.3% | <0.3% |

| Ireland | 47% | 26% | 9% | 2% | 8% | 5% | 2% | 1% |

| Korea, South | 27.2% | 35.1% | 26.1% | 11.3% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.05% |

| Netherlands | 39.5% | 35% | 6.7% | 2.5% | 7.5% | 7% | 1.3% | 0.5% |

| New Zealand | 38% | 32% | 9% | 3% | 9% | 6% | 2% | 1% |

| Poland | 31% | 32% | 15% | 7% | 6% | 6% | 2% | 1% |

| Sweden | 32% | 37% | 10% | 5% | 6% | 7% | 2% | 1% |

| Turkey | 29.8% | 37.8% | 14.2% | 7.2% | 3.9% | 4.7% | 1.6% | 0.8% |

| UK | 37% | 35% | 8% | 3% | 7% | 7% | 2% | 1% |

| USA | 37.4% | 35.7% | 8.5% | 3.4% | 6.6% | 6.3% | 1.5% | 0.6% |

Other blood group systems

The International Society of Blood Transfusion currently recognizes 29 blood group systems (including the ABO and Rh systems). Thus, in addition to the ABO antigens and Rhesus antigens, many other antigens are expressed on the RBC surface membrane. For example, an individual can be AB RhD positive, and at the same time M and N positive (MNS system), K positive ( Kell system), Lea or Leb negative (Lewis system), and so on, being positive or negative for each blood group system antigen. Many of the blood group systems were named after the patients in whom the corresponding antibodies were initially encountered.

Clinical significance

Blood transfusion

Transfusion medicine is a specialized branch of hematology that is concerned with the study of blood groups, along with the work of a blood bank to provide a transfusion service for blood and other blood products. Across the world, blood products must be prescribed by a medical doctor (licensed physician or surgeon) in a similar way as medicines. In the USA, blood products are tightly regulated by the Food and Drug Administration.

Much of the routine work of a blood bank involves testing blood from both donors and recipients to ensure that every individual recipient is given blood that is compatible and is as safe as possible. If a unit of incompatible blood is transfused between a donor and recipient, a severe acute immunological reaction, hemolysis (RBC destruction), renal failure and shock are likely to occur, and death is a possibility. Antibodies can be highly active and can attack RBCs and bind components of the complement system to cause massive hemolysis of the transfused blood.

Patients should ideally receive their own blood or type-specific blood products to minimize the chance of a transfusion reaction. Risks can be further reduced by cross-matching blood, but this may be skipped when blood is required for an emergency. Cross-matching involves mixing a sample of the recipient's blood with a sample of the donor's blood and checking if the mixture agglutinates, or forms clumps. If agglutination is not obvious by direct vision, blood bank technicians usually check for agglutination with a microscope. If agglutination occurs, that particular donor's blood cannot be transfused to that particular recipient. In a blood bank it is vital that all blood specimens are correctly identified, so labeling has been standardized using a barcode system known as ISBT 128.

The blood group may be included on identification tags or on tattoos worn by military personnel, in case they should need an emergency blood transfusion. Frontline German Waffen-SS had such tattoos during World War II. Ironically, this was an easy form of SS identification.

Rare blood types can cause supply problems for blood banks and hospitals. For example Duffy-negative blood occurs much more frequently in people of African origin, and the rarity of this blood type in the rest of the population can result in a shortage of Duffy-negative blood for patients of African ethnicity. Similarly for RhD negative people, there is a risk associated with travelling to parts of the world where supplies of RhD negative blood are rare, particularly East Asia, where blood services may endeavor to encourage Westerners to donate blood.

Hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN)

A pregnant woman can make IgG blood group antibodies if her fetus has a blood group antigen that she does not have. This can happen if some of the fetus' blood cells pass into the mother's blood circulation (e.g. a small fetomaternal hemorrhage at the time of childbirth or obstetric intervention), or sometimes after a therapeutic blood transfusion. This can cause Rh disease or other forms of hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) in the current pregnancy and/or subsequent pregnancies. If a pregnant woman is known to have anti-RhD antibodies, the RhD blood type of a fetus can be tested by analysis of fetal DNA in maternal plasma to assess the risk to the fetus of Rh disease. One of the major advances of twentieth century medicine was to prevent this disease by stopping the formation of Anti-RhD antibodies by RhD negative mothers with an injectable medication called Rho(D) immune globulin. Antibodies associated with some blood groups can cause severe HDN, others can only cause mild HDN and others are not known to cause HDN.

Compatibility

Blood products

In order to provide maximum benefit from each blood donation and to extend shelf-life, blood banks fractionate some whole blood into several products. The most common of these products are packed RBCs, plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate, and fresh frozen plasma (FFP). FFP is quick-frozen to retain the labile clotting factors V and VIII, which are usually administered to patients who have a potentially fatal clotting problem caused by a condition such as advanced liver disease, overdose of anticoagulant, or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Units of packed red cells are made by removing as much of the plasma as possible from whole blood units.

Clotting factors synthesized by modern recombinant methods are now in routine clinical use for hemophilia, as the risks of infection transmission that occur with pooled blood products are avoided.

Red blood cell compatibility

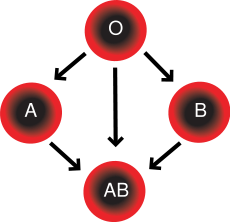

- Blood group AB individuals have both A and B antigens on the surface of their RBCs, and their blood serum does not contain any antibodies against either A or B antigen. Therefore, an individual with type AB blood can receive blood from any group (with AB being preferable), but can donate blood only to another group AB individual.

- Blood group A individuals have the A antigen on the surface of their RBCs, and blood serum containing IgM antibodies against the B antigen. Therefore, a group A individual can receive blood only from individuals of groups A or O (with A being preferable), and can donate blood to individuals with type A or AB.

- Blood group B individuals have the B antigen on the surface of their RBCs, and blood serum containing IgM antibodies against the A antigen. Therefore, a group B individual can receive blood only from individuals of groups B or O (with B being preferable), and can donate blood to individuals with type B or AB.

- Blood group O (or blood group zero in some countries) individuals do not have either A or B antigens on the surface of their RBCs, but their blood serum contains IgM anti-A antibodies and anti-B antibodies against the A and B blood group antigens. Therefore, a group O individual can receive blood only from a group O individual, but can donate blood to individuals of any ABO blood group (ie A, B, O or AB). If anyone needs a blood transfusion in a dire emergency, and if the time taken to process the recipient's blood would cause a detrimental delay, O Negative blood can be issued.

| Recipient | Donor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O− | O+ | A− | A+ | B− | B+ | AB− | AB+ | |

| O− | ||||||||

| O+ | ||||||||

| A− | ||||||||

| A+ | ||||||||

| B− | ||||||||

| B+ | ||||||||

| AB− | ||||||||

| AB+ | ||||||||

Table note

1. Assumes absence of atypical antibodies that would cause an incompatibility between donor and recipient blood, as is usual for blood selected by cross matching.

A RhD negative patient who does not have any anti-RhD antibodies (never being previously sensitized to RhD positive RBCs) can receive a transfusion of RhD positive blood once, but this would cause sensitization to the RhD antigen, and a female patient would become at risk for hemolytic disease of the newborn. If a RhD negative patient has developed anti-RhD antibodies, a subsequent exposure to RhD positive blood would lead to a potentially dangerous transfusion reaction. RhD positive blood should never be given to RhD negative women of childbearing age or to patients with RhD antibodies, so blood banks must conserve Rhesus negative blood for these patients. In extreme circumstances, such as for a major bleed when stocks of RhD negative blood units are very low at the blood bank, RhD positive blood might be given to RhD negative females above child-bearing age or to Rh negative males, providing that they did not have anti-RhD antibodies, to conserve RhD negative blood stock in the blood bank. The converse is not true; RhD positive patients do not react to RhD negative blood.

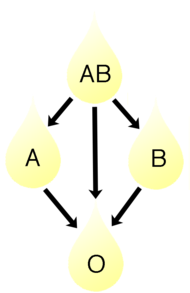

Plasma compatibility

Recipients can receive plasma of the same blood group, but otherwise the donor-recipient compatibility for blood plasma is the converse of that of RBCs: plasma extracted from type AB blood can be transfused to individuals of any blood group; individuals of blood group O can receive plasma from any blood group; and type O plasma can be used only by type O recipients.

| Recipient | Donor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | A | B | AB | |

| O | ||||

| A | ||||

| B | ||||

| AB | ||||

Table note

1. Assumes absence of strong atypical antibodies in donor plasma

Rhesus D antibodies are uncommon, so generally neither RhD negative nor RhD positive blood contain anti-RhD antibodies. If a potential donor is found to have anti-RhD antibodies or any strong atypical blood group antibody by antibody screening in the blood bank, they would not be accepted as a donor (or in some blood banks the blood would be drawn the product would be appropriately labeled); therefore, donor blood plasma issued by a blood bank can be selected to be free of RhD antibodies and free of other atypical antibodies, and such donor plasma issued from a blood bank would be suitable for a recipient who may be RhD positive or RhD negative, as long as blood plasma and the recipient are ABO compatible.

Universal donors and universal recipients

With regard to transfusions of whole blood or packed red blood cells, individuals with type O negative blood are often called universal donors, and those with type AB positive blood are called universal recipients (Strictly speaking this is not true and individuals with Hh antigen system (also known as the Bombay blood group) are the universal donors). Although blood donors with particularly strong anti-A, anti-B or any atypical blood group antibody are excluded from blood donation, the terms universal donor and universal recipient are an over-simplification, because they only consider possible reactions of the recipient's anti-A and anti-B antibodies to transfused red blood cells, and also possible sensitization to RhD antigens. The possible reactions of anti-A and anti-B antibodies present in the transfused blood to the recipients RBCs are not considered, because a relatively small volume of plasma containing antibodies is transfused.

By way of example; considering the transfusion of O RhD negative blood (universal donor blood) into a recipient of blood group A RhD positive, an immune reaction between the recipient's anti-B antibodies and the transfused RBCs is not anticipated. However, the relatively small amount of plasma in the transfused blood contains anti-A antibodies, which could react with the A antigens on the surface of the recipients RBCs, but a significant reaction is unlikely because of the dilution factors. Rhesus D sensitization is not anticipated.

Additionally, red blood cell surface antigens other than A, B and Rh D, might cause adverse reactions and sensitization, if they can bind to the corresponding antibodies to generate an immune response. Transfusions are further complicated because platelets and white blood cells (WBCs) have their own systems of surface antigens, and sensitization to platelet or WBC antigens can occur as a result of transfusion.

With regard to transfusions of plasma, this situation is reversed. Type O plasma can be given only to O recipients, while AB plasma (which does not contain anti-A or anti-B antibodies) can be given to patients of any ABO blood group.

Conversion

In April 2007 a method was discovered to convert blood types A, B, and AB to O, using enzymes. This method is still experimental and the resulting blood has yet to undergo human trials. The method specifically removes or converts antigens on the red blood cells, so other antigens and antibodies would remain. This does not help plasma compatibility, but that is a lesser concern since plasma has much more limited clinical utility in transfusion and is much easier to preserve.

History

The two most significant blood group systems were discovered during early experiments with blood transfusion: the ABO group in 1901 and the Rhesus group in 1937. Development of the Coombs test in 1945, the advent of transfusion medicine, and the understanding of hemolytic disease of the newborn led to discovery of more blood groups, and now 29 human blood group systems are recognized by the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT), and across the 29 blood groups, over 600 different blood group antigens have been found, but many of these are very rare or are mainly found in certain ethnic groups. Blood types have been used in forensic science and in paternity testing, but both of these uses are being replaced by genetic fingerprinting, which provides greater certitude.

Cultural beliefs regarding blood types

The Japanese blood type theory of personality is a popular belief that a person's ABO blood type is predictive of their personality, character, and compatibility with others. It was a serious scientific hypothesis which was proposed early in the 20th century, which gained currency within the Japanese public. This theory has long since been rejected by the scientific community. (For a proponent, see Masahiko Nomi). This belief has been carried over to a certain extent into other parts of East Asia, and South Korea. In Japan, asking someone their blood type is considered as normal as asking their astrological sign. It is also common for Japanese-made video games (especially role-playing games) and the manga series to include blood type with character descriptions.

The blood type diet is an American system whereby people seek improved health by modifying their food intake and lifestyle according to their ABO blood group and secretor status. This system includes some reference to differences in personality, but not to the extent typical of the Japanese theory.