Giraffe

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Mammals

| Giraffe | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||

| Giraffa camelopardalis Linnaeus, 1758 |

||||||||||||||

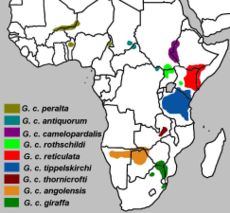

Range map

|

The giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) is an African even-toed ungulate mammal, the tallest of all land-living animal species, and the largest ruminant. Males can be 4.8 to 5.5 metres (16 to 18 feet) tall and weigh up to 1,700 kilograms (3,800 pounds). The record-sized bull, shot in Kenya in 1934, was 5.87 m (19.2 ft) tall and weighed approximately 2,000 kg (4,400 lb). Females are generally slightly shorter, and weigh less than the males do.

The giraffe is related to deer and cattle, but is placed in a separate family, the Giraffidae, consisting only of the giraffe and its closest relative, the okapi. Its range extends from Chad to South Africa.

Giraffes can inhabit savannas, grasslands, or open woodlands. They prefer areas enriched with acacia growth. They drink large quantities of water and, as a result, they can spend long periods of time in dry, arid areas. When searching for more food they will venture into areas with denser foliage.

Etymology

The species name camelopardalis (camelopard) is derived from its early Roman name, where it was described as having characteristics of both a camel and a leopard. The English word camelopard first appeared in the 14th century and survived in common usage well into the 19th century. The Afrikaans language retained it. The Arabic word الزرافة ziraafa or zurapha, meaning "assemblage" (of animals), or just "tall", was used in English from the sixteenth century on, often in the Italianate form giraffa.

Taxonomy and evolution

Giraffids evolved from a 3 metre (10 ft) tall antelope-like mammal which roamed Europe and Asia 30-50 million years ago. The earliest giraffid was the Climacoceras, which still resembled deer, having large antler-like ossicones. It first appeared in the early Miocene period. As the lineage went on the genuses Palaeotragus and Samotherium appeared in the early to mid-Miocene. One species of Palaeotragus developed more giraffe-like ossicones. They both were tall at the shoulder but still had short necks. For there the genus Giraffa evolved in the Pliocene period and Okapia evolved in the Pleistocene. The modern long-necked giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis, appeared 1 million years ago.

Classification

There are nine generally accepted subspecies, differentiated by colour and pattern variations and range:

- Reticulated or Somali Giraffe (G.c. reticulata) — large, polygonal liver-coloured spots outlined by a network of bright white lines. The blocks may sometimes appear deep red and may also cover the legs. Range: northeastern Kenya, Ethiopia, Somalia.

- Angolan or Smoky Giraffe (G.c. angolensis) — large spots and some notches around the edges, extending down the entire lower leg. Range: Angola, Zambia.

- Kordofan Giraffe (G.c. antiquorum) — smaller, more irregular spots that cover the inner legs. Range: western and southwestern Sudan.

- Masai or Kilimanjaro Giraffe (G.c. tippelskirchi) — jagged-edged, vine-leaf shaped spots of dark chocolate on a yellowish background. Range: central and southern Kenya, Tanzania.

- Nubian Giraffe (G.c. camelopardalis) — large, four-sided spots of chestnut brown on an off-white background and no spots on inner sides of the legs or below the hocks. Range: eastern Sudan, northeast Congo.

- Rothschild Giraffe or Baringo Giraffe or Ugandan Giraffe (G.c. rothschildi) — deep brown, blotched or rectangular spots with poorly defined cream lines. Hocks may be spotted. Range: Uganda, north-central Kenya.

- South African Giraffe (G.c. giraffa) — rounded or blotched spots, some with star-like extensions on a light tan background, running down to the hooves. Range: South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique.

- Thornicroft or Rhodesian Giraffe (G.c. thornicrofti) — star-shaped or leafy spots extend to the lower leg. Range: eastern Zambia.

- West African or Nigerian Giraffe (G.c. peralta) — numerous pale, yellowish red spots. Range: Niger, Cameroon.

Some scientists regard Kordofan and West African Giraffes as a single subspecies; similarly with Nubian and Rothschild's Giraffes, and with Angolan and South African Giraffes. Further, some scientists regard all populations except the Masai Giraffes as a single subspecies. By contrast, scientists have proposed four other subspecies — Cape Giraffe (G.c. capensis), Lado Giraffe (G.c. cottoni), Congo Giraffe (G.c. congoensis), and Transvaal Giraffe (G.c. wardi) — but none of these is widely accepted.

Though giraffes of these populations interbreed freely under conditions of captivity, suggesting that they are subspecific populations, genetic testing published in 2007 has been interpreted to show that there may be at least six species of giraffe that are reproductively isolated and not interbreeding, even though no natural obstacles, like mountain ranges or impassable rivers block their mutual access. In fact, the study found that the two giraffe populations that live closest to each other— the reticulated giraffe (G. camelopardalis reticulata) of north Kenya, and the Masai giraffe (G. c. tippelskirchi) in south Kenya— separated genetically between 0.13 and 1.62 million years BP, judging from genetic drift in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA.

The implications for conservation of as many as eleven such cryptic species and sub-species were summarised by David Brown for BBC News: "Lumping all giraffes into one species obscures the reality that some kinds of giraffe are on the brink. Some of these populations number only a few hundred individuals and need immediate protection."

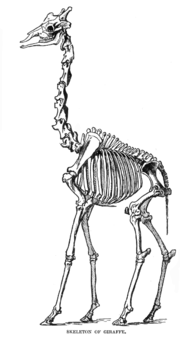

Anatomy and morphology

Male giraffes are around 4.8-5.5 m (16-19 ft) tall at the horn tips, and normally weigh 1300-1700 kg (2900-3800 lb) Females are 30-60 cm (1-2 ft) shorter and weigh about 200-400 kg (400-800 lb) less than males. Giraffes have spots covering their entire bodies, except their underbellies, with each giraffe having a unique pattern of spots.

Horns

Both sexes have horns, although the horns of a female are smaller. The prominent horns are formed from ossified cartilage and are called ossicones. The appearance of horns is a reliable method of identifying the sex of giraffes, with the females displaying tufts of hair on the top of the horns, where as males' horns tend to be bald on top — an effect of necking in combat. Males sometimes develop calcium deposits which form bumps on their skull as they age, which can give the appearance of up to three further horns.

Neck

Giraffes have long necks, which they use to browse the leaves of trees. They possess seven vertebrae in the neck (the usual number for a mammal) that are elongated. The vertebrae are separated by highly flexible joints. The base of the neck has spines which project upward and form a hump over the shoulders. They have anchor muscles that hold the neck upright.

Legs and pacing

Giraffes also have slightly elongated forelegs, about 10% longer than their hind legs. The pace of the giraffe is an amble, though when pursued it can run extremely fast. It can not sustain a lengthy chase. Its leg length compels an unusual gait with the left legs moving together followed by right (similar to pacing) at low speed, and the back legs crossing outside the front at high speed. When hunting adult giraffes, lions try to knock the lanky animal off its feet and pull it down. Giraffes are difficult and dangerous prey though, and when attacked the giraffe defends itself by kicking with great force. A single well-placed kick from an adult giraffe can shatter a lion's skull or break its spine. Lions are the only predators which pose a serious threat to an adult giraffe.

Circulatory system

Modifications to the giraffe's structure have evolved, particularly to the circulatory system. A giraffe's heart, which can weigh up to 10 kg (22 lb) and measure about 60 cm (2 ft) long, has to generate around double the normal blood pressure for an average large mammal in order to maintain blood flow to the brain against gravity. In the upper neck, a complex pressure-regulation system called the rete mirabile prevents excess blood flow to the brain when the giraffe lowers its head to drink. Conversely, the blood vessels in the lower legs are under great pressure (because of the weight of fluid pressing down on them). In other animals such pressure would force the blood out through the capillary walls; giraffes, however, have a very tight sheath of thick skin over their lower limbs which maintains high extravascular pressure in exactly the same way as a pilot's g-suit.

Behaviour

Social structure and breeding habits

Female giraffes associate in groups of a dozen or so members, occasionally including a few younger males. Younger males tend to live in "bachelor" herds, with older males often leading solitary lives. Reproduction is polygamous, with a few older males impregnating all the fertile females in a herd. Male giraffes determine female fertility by tasting the female's urine in order to detect estrus, in a multi-step process known as the Flehmen response.

Giraffes will mingle with the other herbivores in the African bush. They are beneficial to be around because of their height. A giraffe is tall enough to have a much wider scope of an area and will watch out for predators.

Reproduction

Giraffe gestation lasts between 14 and 15 months, after which a single calf is born. The mother gives birth standing up and the embryonic sack usually bursts when the baby falls to the ground. Newborn giraffes are about 1.8 m (6 ft) tall.

Within a few hours of being born, calves can run around and are indistinguishable from a week-old calf; however, for the first two weeks, they spend most of their time lying down, guarded by the mother. The young can fall prey to lions, leopards, spotted hyenas, and wild dogs. It has been speculated that their characteristic spotted pattern provides a certain degree of camouflage. Only 25 to 50% of giraffe calves reach adulthood; the life expectancy is between 20 and 25 years in the wild and 28 years in captivity (Encyclopedia of Animals).

Necking

As noted above, males often engage in necking, which has been described as having various functions. One of these is combat. Battles can be fatal, but are more often less severe. The longer the neck, and the heavier the head at the end of the neck, the greater the force a giraffe is able to deliver in a blow. It has also been observed that males that are successful in necking have greater access to estrous females, so the length of the neck may be a product of sexual selection.

After a necking duel, a giraffe can land a powerful blow with his head — occasionally knocking a male opponent to the ground. These fights rarely last more than a few minutes or end in physical harm.

Another function of necking is affectionate and sexual, in which two males will caress and court each other, leading up to mounting and climax. Same sex relations are more frequent than heterosexual behaviour. In one area 94% of mounting incidents were of a homosexual nature. The proportion of same sex courtships varies between 30 and 75%, and at any given time one in twenty males will be engaged in affectionate necking behaviour with another male. Females, on the other hand, only appear to have same sex relations in 1% of mounting incidents.

Stereotypic behaviour

Many animals when kept in captivity, such as in zoos, display abnormal behaviours. Such unnatural behaviours are known as stereotypic behaviours. In particular, giraffes show distinct patterns of stereotypic behaviours when removed from their natural environment. Due to a subconscious response to suckle milk from their mother, something which many human-reared giraffes and other captive animals do not experience, giraffes resort instead to excessive tongue use on inanimate objects.

Due to the obvious social and cultural discomfort associated with the addition of milk delivery devices, animal enclosures are often enriched with other stimuli, such as food and mental distractions (toys, scent markings etc.). This operates as a distraction, removing the giraffe’s focus from its instinctual tendencies towards suckling, resulting in tongue lolling and licking of objects in close proximity.

Feeding and cleaning

The giraffe browses on the twigs of trees, preferring trees of the genus Mimosa; but it appears that it can live without inconvenience on other vegetable food. A giraffe can eat 63 kg (140 lb) of leaves and twigs daily. As ruminants, they first chew their food, swallow for processing and then visibly regurgitate the semi-digested cud up their necks and back into the mouth, in order to chew again. This process is usually repeated several times for each mouthful.

A giraffe will clean off any bugs that appear on its face with its extremely long tongue (about 45 cm/18 in). The tongue is tough on account of the giraffe's diet, which can include thorns from the trees that they eat. In Southern Africa, giraffes feed on all acacias, especially Acacia erioloba, and possess a specially-adapted tongue and lips that are tough enough to withstand, or even ignore, the vicious thorns of this plant.

Sleep

The giraffe has one of the shortest sleep requirements of any mammal, which is between 10 minutes and two hours in a 24-hour period, averaging 1.9 hours per day.

Sounds

Although generally quiet and not vocal, giraffes have been heard to make various sounds. Courting males will emit loud coughs. Females will call their young by whistling or bellowing. Calves will bleat, moo, or make mewing sounds. In addition, giraffes will grunt, snort, hiss, or make strange flute-like sounds. Recent research has shown evidence that the animal communicates at an infrasound level.

Conservation

Giraffes are hunted for their hides, hair, and meat. In addition, habitat destruction also hurts the giraffe. In the Sahel trees are cut down for firewood and to make way for livestock. Normally, giraffes are able to cope with livestock since they feed in the trees above their heads. The giraffe population is shrinking in West Africa. However, the populations in eastern and southern Africa are stable and, due to the popularity of privately-owned game ranches and sanctuaries (i.e. Bour-Algi Giraffe Sanctuary), are expanding. The giraffe is a protected species in most of its range. The total African giraffe population has been estimated to range from 110,000 to 150,000. Kenya (45,000), Tanzania (30,000), and Botswana (12,000), have the largest national populations.

An unexpected danger to giraffes in captivity is that, as they are typically the tallest objects in a zoo, giraffes are at increased risk of being struck by lightning. In the wild, this hazard is reduced by the presence of trees; as well, the giraffe's natural habitat range has an extremely low occurrence of lightning -- NASA's satellite lightning detection system indicates that the area receives an average of less than one cloud-to-ground flash per square kilometre per year.

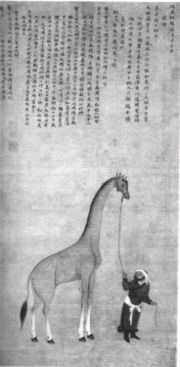

In art and culture

Giraffes can be seen in paintings, including the famous painting of a giraffe which was taken from Africa to China by Admiral Zheng He in 1414. The giraffe was placed in a Ming Dynasty zoo.

The Medici giraffe was a giraffe presented to Lorenzo de' Medici in 1486. It caused a great stir on its arrival in Florence, being reputedly the first living giraffe to be seen in Italy since the days of Ancient Rome. Another famous giraffe, called Zarafa, was brought from Africa to Paris in the early 1800s and kept in a menagerie for 18 years.

Giraffe is a novel by the author J. M. Ledgard. The work concerns a true incident in which 49 giraffes were slaughtered in the Czech Republic (then Czechoslovakia) in 1975 following the suspected outbreak of disease amongst the group. The novel contains extensive information about the species, including the long history of European fascination with the beast and its captivity in zoos.

Notable fictional giraffes include:

- Toys "R" Us mascot Geoffrey the Giraffe. He was originally portrayed as a cartoon giraffe but in the 2001 commercials he was portrayed as a real-life giraffe who talks; an animatronic version of Geoffrey the Giraffe (created by Stan Winston Studios), was voiced by Jim Hanks in commercials for radio and television.

- Longrack of the Transformers universe

- Girafarig from the Pokémon franchise

- Melman from Madagascar

Giraffes have also appeared as background characters in various other animated works such as Dumbo and The Lion King.