Jackson Pollock

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Artists

| Jackson Pollock | |

Photographer Hans Namuth extensively documented Pollock's unique painting techniques. |

|

| Birth name | Paul Jackson Pollock |

| Born | January 28, 1912 Cody, Wyoming |

| Died | August 11, 1956 (aged 44) Springs, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Field | Painter |

| Movement | Abstract expressionism |

| Patrons | Peggy Guggenheim |

Paul Jackson Pollock ( January 28, 1912 – August 11, 1956) was an influential American painter and a major force in the abstract expressionist movement. He was married to noted abstract painter Lee Krasner.

Early life

Pollock was born in Cody, Wyoming in 1912, the youngest of five sons. His father was a farmer and later a land surveyor for the government. He grew up in Arizona and Chico, California, studying at Los Angeles' Manual Arts High School. During his early life, he experienced Indian culture while on surveying trips with his father. In 1929, following his brother Charles, he moved to New York City, where they both studied under Thomas Hart Benton at the Art Students League of New York. Benton's rural American subject matter shaped Pollock's work only fleetingly, but his rhythmic use of paint and his fierce independence were more lasting influences. From 1938 to 1942, he worked for the Federal Art Project.

The Springs period and the unique technique

In October 1945, Pollock married another important American painter, Lee Krasner, and in November they moved to what is now known as the Pollock-Krasner House and Studio in Springs on Long Island, New York. Peggy Guggenheim loaned them the down payment for the wood-frame house with a nearby barn that Pollock made into a studio. It was there that he perfected the technique of working spontaneously with liquid paint.

Pollock was introduced to the use of liquid paint in 1936, at an experimental workshop operated in New York City by the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. He later used paint pouring as one of several techniques in canvases of the early 1940s, such as "Male and Female" and "Composition with Pouring I." After his move to Springs, he began painting with his canvases laid out on the studio floor, and developed what was later called his "drip" technique. The drip technique required paint with a fluid viscosity so Pollock turned to then new synthetic resin-based paints, called "gloss enamel", made for industrial purposes such as spray-painting cars. During WWII, these gloss enamel paints were more available than typical artist’s oil paints, and they were cheaper. Pollock described this use of household and industrial paints, instead of artist’s paints, as "a natural growth out of a need". He used hardened brushes, sticks and even basting syringes as paint applicators. He would poke a hole in the bottom of a tin can of paint to get an extended drip line. Pollock's technique of pouring and dripping paint is thought to be one of the origins of the term action painting. With this technique, Pollock was able to achieve a more immediate means of creating art, the paint now literally flying from his chosen tool onto the canvas. By defying the conventional way of painting on an upright surface, he added a new dimension, literally, by being able to view and apply paint to his canvases from all directions.

In the process of making paintings in this way he moved away from figurative representation, and challenged the Western tradition of using easel and brush, as well as moving away from use only of the hand and wrist; as he used his whole body to paint. In 1956 Time magazine dubbed Pollock "Jack the Dripper" as a result of his unique painting style.

| “ | My painting does not come from the easel. I prefer to tack the unstretched canvas to the hard wall or the floor. I need the resistance of a hard surface. On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting. | ” |

| “ | I continue to get further away from the usual painter's tools such as easel, palette, brushes, etc. I prefer sticks, trowels, knives and dripping fluid paint or a heavy impasto with sand, broken glass or other foreign matter added. | ” |

| “ | When I am in my painting, I'm not aware of what I'm doing. It is only after a sort of 'get acquainted' period that I see what I have been about. I have no fear of making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through. It is only when I lose contact with the painting that the result is a mess. Otherwise there is pure harmony, an easy give and take, and the painting comes out well. | ” |

Pollock observed Indian sandpainting demonstrations in the 1940s. Other influences on his dripping technique include the Mexican muralists and also Surrealist automatism. Pollock denied "the accident"; he usually had an idea of how he wanted a particular piece to appear. It was about the movement of his body, over which he had control, mixed with the viscous flow of paint, the force of gravity, and the way paint was absorbed into the canvas. The mix of the uncontrollable and the controllable. Flinging, dripping, pouring, spattering, he would energetically move around the canvas, almost as if in a dance, and would not stop until he saw what he wanted to see. Studies by Taylor, Micolich and Jonas have explored the nature of Pollock's technique and have determined that some of these works display the properties of mathematical fractals; and that the works become more fractal-like chronologically through Pollock's career. They even go on to speculate that on some level, Pollock may have been aware of the nature of chaotic motion, and was attempting to form what he perceived as a perfect representation of mathematical chaos - more than ten years before Chaos Theory itself was discovered.

In 1950 Hans Namuth, a young photographer, wanted to photograph and film Pollock at work. Pollock promised to start a new painting especially for the photographic session, but when Namuth arrived, Pollock apologized and told him the painting was finished. Namuth's comment upon entering the studio:

| “ | A dripping wet canvas covered the entire floor. . . . There was complete silence. . . . Pollock looked at the painting. Then, unexpectedly, he picked up can and paint brush and started to move around the canvas. It was as if he suddenly realized the painting was not finished. His movements, slow at first, gradually became faster and more dance like as he flung black, white, and rust colored paint onto the canvas. He completely forgot that Lee and I were there; he did not seem to hear the click of the camera shutter. . . My photography session lasted as long as he kept painting, perhaps half an hour. In all that time, Pollock did not stop. How could one keep up this level of activity? Finally, he said 'This is it.' | ” |

| “ | Pollock’s finest paintings… reveal that his all-over line does not give rise to positive or negative areas: we are not made to feel that one part of the canvas demands to be read as figure, whether abstract or representational, against another part of the canvas read as ground. There is not inside or outside to Pollock’s line or the space through which it moves…. Pollock has managed to free line not only from its function of representing objects in the world, but also from its task of describing or bounding shapes or figures, whether abstract or representational, on the surface of the canvas.(Karmel 132) | ” |

The 1950s and beyond

Pollock's most famous paintings were during the "drip period" between 1947 and 1950. He rocketed to popular status following an August 8, 1949 four-page spread in Life Magazine that asked, "Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?" At the peak of his fame, Pollock abruptly abandoned the drip style.

Pollock's work after 1951 was darker in color, including a collection in black on unprimed canvases, followed by a return to colour and he reintroduced figurative elements. Pollock had moved to a more commercial gallery and there was great demand from collectors for new paintings. In response to this pressure his alcoholism deepened.

From naming to numbering

Pollock wanted an end to the viewer's search for representational elements in his paintings, thus he abandoned naming them and started numbering them instead. Of this, Pollock commented: "...look passively and try to receive what the painting has to offer and not bring a subject matter or preconceived idea of what they are to be looking for." Pollock's wife, Lee Krasner, said Pollock "used to give his pictures conventional titles... but now he simply numbers them. Numbers are neutral. They make people look at a picture for what it is - pure painting."

Death

Pollock did not paint at all in 1955. After struggling with alcoholism his whole life, Pollock's career was cut short when he died in an alcohol-related, single car crash in his Oldsmobile convertible, less than a mile from his home in Springs, New York on August 11, 1956 at the age of 44. One of his passengers, Edith Metzger, died, while the other passenger, Pollock's girlfriend Ruth Kligman, survived. After his death, Pollock's wife, Lee Krasner, managed his estate and ensured that Pollock's reputation remained strong in spite of changing art-world trends. They are buried in Green River Cemetery in Springs with a large boulder marking his grave and a smaller one marking hers.

Legacy

The Pollock-Krasner House and Studio is owned and administered by the Stony Brook Foundation, a non-profit affiliate of the State University of New York at Stony Brook. There are regular tours of the house and studio from May - October.

In 2000, the biographical film Pollock was released. Marcia Gay Harden won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her portrayal of Lee Krasner. The movie was the project of Ed Harris who portrayed Pollock and directed it. He was nominated for Academy Award for Best Actor.

In November 2006 Pollock's " No. 5, 1948" became the world's most expensive painting, when it was auctioned to an undisclosed bidder for the sum of $140,000,000. The previous owner was film and music-producer David Geffen. It is rumored that the current owner is a German businessman and art collector.

An ongoing debate rages over whether 24 paintings and drawings found in a Wainscott, New York locker in 2003 are Pollock originals. Physicists have argued over whether fractals can be used to authenticate the paintings. Analysis of the pigments shows some were not yet patented at the time of Pollock's death, although they may have been available to Pollock through a dealer. The debate is still inconclusive.

In 2006 a documentary, Who the Fuck Is Jackson Pollock?, was released which featured a truck driver named Teri Horton who bought what may be a Pollock painting worth millions at a thrift store for five dollars.

Relationship to Native American art

Pollock stated: “I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, since this way I can walk round it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting. This is akin to the methods of the Indian sand painters of the West.”

Critical debate

Pollock's work has always polarized critics and has been the focus of many important critical debates.

Harold Rosenberg spoke of the way Pollock's work had changed painting, "what was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event. The big moment came when it was decided to paint 'just to paint.' The gesture on the canvas was a gesture of liberation from value — political, aesthetic, moral."

Clement Greenberg supported Pollock's work on formalistic grounds. It fit well with Greenberg's view of art history as being about the progressive purification in form and elimination of historical content. He therefore saw Pollock's work as the best painting of its day and the culmination of the Western tradition going back via Cubism and Cézanne to Monet.

Posthumous exhibitions of Pollock's work had been sponsored by the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an organization to promote American culture and values backed by the CIA. Certain left wing scholars, most prominently Eva Cockcroft, argue that the U.S. government and wealthy elite embraced Pollock and abstract expressionism in order to place the United States firmly in the forefront of global art and devalue socialist realism. In the words of Cockcroft, Pollock became a 'weapon of the Cold War'.

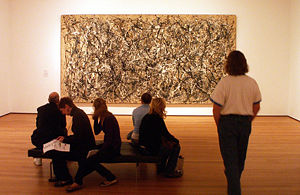

Painter Norman Rockwell's work Connoisseur also appears to make a commentary on the Pollock style. The painting features what seems to be a rather upright man in a suit standing before a Jackson Pollock splatter painting. The contrast between the man and the Pollock painting, along with the construction of the scene, seems to emphasize the disparity between the comparatively unrecognizable Jackson Pollock style and traditional figure and landscape based art styles, as well as the monumental changes in the cultural sense of aesthetics brought on by the modern art movement.

Others such as artist, critic, and satirist Craig Brown, have been "astonished that decorative 'wallpaper', essentially brainless, could gain such a position in art history alongside Giotto, Titian, and Velazquez."

Reynolds News in a 1959 headline said, "This is not art — it's a joke in bad taste."

List of major works

- (1942) Male and Female Philadelphia Museum of Art

- (1942) Stenographic Figure Museum of Modern Art

- (1943) Mural University of Iowa Museum of Art

- (1943) Moon-Woman Cuts the Circle

- (1942) Stenographic Figure Museum of Modern Art

- (1943) The She-Wolf Museum of Modern Art

- (1943) Blue (Moby Dick) Ohara Museum of Art

- (1945) Troubled Queen Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- (1946) Eyes in the Heat Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

- (1946) The Key Art Institute of Chicago

- (1946) The Tea Cup Collection Frieder Burda

- (1946) Shimmering Substance, from The Sounds In The Grass Museum of Modern Art

- (1947) Full Fathom Five Museum of Modern Art

- (1947) Cathedral

- (1947) Enchanted Forest Peggy Guggenheim Collection

- (1948) Painting

- (1948) Number 5 (4ft x 8ft) Private collection

- (1948) Number 8

- (1948) Summertime: Number 9A Tate Modern

- (1949) Number 3

- (1949) Number 10 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- (1950) Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist) National Gallery of Art

- (1950) Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), 1950 Metropolitan Museum of Art

- (1950) Number 29, 1950 National Gallery of Canada

- (1950) One: Number 31, 1950 Museum of Modern Art

- (1950) No. 32

- (1951) Number 7 National Gallery of Art

- (1952) Convergence Albright-Knox Art Gallery

- (1952) Blue Poles: No. 11, 1952 National Gallery of Australia

- (1953) Portrait and a Dream

- (1953) Easter and the Totem The Museum of Modern Art

- (1953) Ocean Greyness

- (1953) The Deep