James Buchanan

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: USA Presidents

|

James Buchanan

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office March 4, 1857 – March 4, 1861 |

|

| Vice President | John C. Breckinridge (1857–1861) |

| Preceded by | Franklin Pierce |

| Succeeded by | Abraham Lincoln |

|

17th United States Secretary of State

|

|

| In office March 10, 1845 – March 7, 1849 |

|

| President | James K. Polk |

| Preceded by | John C. Calhoun |

| Succeeded by | John M. Clayton |

|

United States Senator

from Pennsylvania |

|

| In office December 6, 1834 – March 5, 1845 |

|

| Preceded by | William Wilkins |

| Succeeded by | Simon Cameron |

|

|

|

| Born | April 23, 1791 Mercersburg, Pennsylvania |

| Died | June 1, 1868 (aged 77) Lancaster, Pennsylvania |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | None ( Bachelor) |

| Alma mater | Dickinson College |

| Occupation | Lawyer, Diplomat |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

| Signature | |

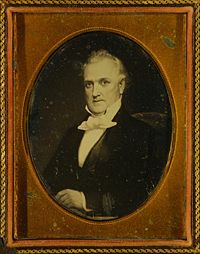

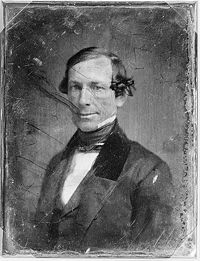

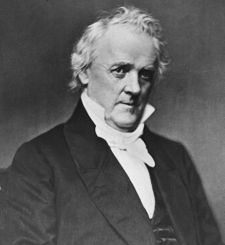

James Buchanan, Jr. ( April 23, 1791 – June 1, 1868) was the fifteenth President of the United States (1857–1861). To date he is the only President from Pennsylvania and the only President never to marry. As president he was a " doughface" who battled Stephen A. Douglas for control of the Democratic Party. As Southern states declared their secession in the lead-up to the American Civil War, he held that secession was illegal but that going to war to stop it was also illegal. Taking his own advice, he did nothing.

Early life

James Buchanan was born in a log cabin at Cove Gap, near Mercersburg, Franklin County, Pennsylvania, on April 23, 1791, to James Buchanan and Elizabeth Speer. He was the second of 10 children, two of whom did not survive past infancy. The Buchanan family claims descent from King James I of Scotland. In 1802, he moved to Mercersburg with his parents, where he was privately tutored. He later attended the village academy and graduated from Dickinson College, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. At one point, he was expelled from Dickinson for wild behavior and bad conduct, but after pleading for a second chance, he graduated with honours three years later on September 7, 1809. Later that year he moved to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. For the next three years he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1812. He then opened a practice in Lancaster. A dedicated Federalist, he strongly opposed the War of 1812 on the grounds that it was an unnecessary conflict. Nevertheless, when the British invaded neighboring Maryland, he joined a volunteer light dragoon unit and served in the defense of Baltimore.

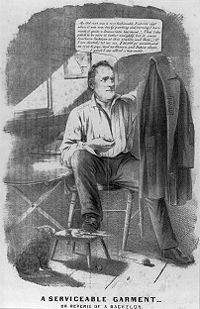

An 1856 cartoon by Nathaniel Currier depicts Buchanan sitting in his room examining the "Cuba" patch he has sewn on his jacket. As Minister to Britain, he pressed unsuccessfully for the purchase of Cuba in what is known as the Ostend Manifesto.

Political career

Buchanan started his political career in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives from 1814–1816. He was elected to the 17th United States Congress and to the four succeeding Congresses ( March 4, 1821 – March 4, 1831). He was chairman of the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary (Twenty-first Congress). He was not a candidate for renomination in 1830. Buchanan served as one of the managers appointed by the House of Representatives in 1830 to conduct the impeachment proceedings against James H. Peck, judge of the United States District Court for the District of Missouri. Buchanan served as ambassador to Russia from 1832 to 1834.

With his original party of choice, the Federalists, long defunct, Buchanan was elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate to fill a vacancy and served from December 1834; he was reelected in 1837 and 1843 and resigned in 1845. He was chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations (Twenty-fourth through Twenty-sixth Congresses).

After the death of Supreme Court Justice Henry Baldwin in 1844, Buchanan was nominated (and refused the nomination) by President Polk to serve as a Justice of the Supreme Court (the seat was filled by Robert Cooper Grier).

Buchanan served as Secretary of State in the Cabinet of President James K. Polk from 1845 to 1849, during which time he negotiated the 1846 Oregon Treaty establishing the 49th parallel as the northern boundary in the western U.S. No Secretary of State has become President since James Buchanan, although William Howard Taft, the 27th President of the United States, often served as Acting Secretary of State during the Theodore Roosevelt administration.

In 1852, Buchanan was named president of the Board of Trustees of Franklin and Marshall College in his hometown of Lancaster. He served in this capacity until 1866.

He served as minister to the Court of St. James's (Britain) from 1853 to 1856, during which time he helped to draft the Ostend Manifesto, which proposed the purchase of Cuba from Spain in order to extend slavery. The Manifesto was a major blunder for the Pierce administration and greatly weakened support for Manifest Destiny.

Election of 1856

The Democrats nominated Buchanan in 1856 largely because he was in England during the Kansas-Nebraska debate and thus remained untainted by either side of the issue. He was nominated on the 17th ballot. Although he did not want to run, he accepted the nomination.

Former president Millard Fillmore's " Know-Nothing" candidacy helped Buchanan defeat John C. Frémont, the first Republican candidate for president in 1856, and he served from March 4, 1857, to March 4, 1861.

With regard to the growing schism in the country, as President-elect, he intended to sit out the crisis by maintaining a sectional balance in his appointments and persuading the people to accept constitutional law as the Supreme Court interpreted it. The court was considering the legality of restricting slavery in the territories, and two justices hinted to Buchanan what the decision would be.

Presidency 1857–1861

The Dred Scott case

In his inaugural address, besides promising not to run again, Buchanan referred to the territorial question as "happily, a matter of but little practical importance" since the Supreme Court was about to settle it "speedily and finally." Two days later, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney (a fellow alumnus of Dickinson College) delivered the Dred Scott Decision, asserting that Congress had no constitutional power to exclude slavery in the territories. Much of Taney’s written judgment is widely interpreted as obiter dictum — statements made by a judge that are unnecessary to the outcome of the case, which in this case, while they delighted Southerners, created a furor in the North. Buchanan was widely believed to have been personally involved in the outcome of the case, with many Northerners recalling Taney whispering to Buchanan during Buchanan's inauguration. Buchanan wished to see the territorial question resolved by the Supreme Court. To further this, Buchanan personally lobbied his fellow Pennsylvanian Justice Robert Cooper Grier to vote with the majority in that case to uphold the right of owning slave property. Abraham Lincoln denounced him as an accomplice of the Slave Power, which Lincoln saw as a conspiracy of slaveowners to seize control of the federal government and nationalize slavery.

Bleeding Kansas

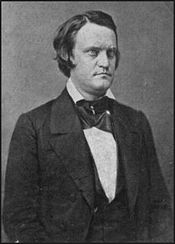

Buchanan, however, faced further trouble on the territorial question. Buchanan threw the full prestige of his administration behind congressional approval of the Lecompton Constitution in Kansas, which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state, going so far as to offer patronage appointments and even cash bribes in exchange for votes. The Lecompton government was unpopular to Northerners, as it was dominated by slaveholders who had enacted laws curtailing the rights of non-slaveholders. Even though the voters in Kansas had rejected the Lecompton Constitution, Buchanan managed to pass his bill through the House, but it was blocked in the Senate by Northerners led by Stephen A. Douglas. Eventually, Congress voted to call a new vote on the Lecompton Constitution, a move which infuriated Southerners. Buchanan and Douglas engaged in an all-out struggle for control of the party in 1859–60, with Buchanan using his patronage powers and Douglas rallying the grass roots; Buchanan lost control of the greatly weakened party.

Views on slavery

Buchanan personally favored slaveowners' rights, and he sympathized with the slave-expansionists who coveted Cuba. Buchanan despised both abolitionists and free-soil Republicans, lumping the two together. He fought the opponents of the Slave Power. In his third annual message Buchanan claimed that the slaves were "treated with kindness and humanity... Both the philanthropy and the self-interest of the master have combined to produce this humane result." Shortly after his election, he assured a southern Senator that the "great object" of his administration would be "to arrest, if possible, the agitation of the Slavery question at the North and to destroy sectional parties. Should a kind Providence enable me to succeed in my efforts to restore harmony to the Union, I shall feel that I have not lived in vain." As historian Kenneth Stampp concludes, "Buchanan was the consummate ' doughface,' a northern man with southern principles."

Financial Panic

Economic troubles also plagued Buchanan's administration with the outbreak of the Panic of 1857. The government suddenly faced a shortfall of revenue, partly because of the Democrats' successful push to lower the tariff. Buchanan's administration, at the behest of Treasury Secretary Howell Cobb, began issuing deficit financing for the government, a move which flew in the face of two decades of Democratic support for hard money policies and allowed Republicans to attack Buchanan for financial mismanagement.

Utah War

In March 1857, Buchanan received inflated reports that Governor Brigham Young of the Mormon-dominated Utah Territory was planning revolt. In November of that year, Buchanan sent the Army to replace Young as Governor with the non-Mormon Alfred Cumming without either confirming the reports or notifying Young of his replacement. Years of anti-Mormon rhetoric in Washington combined with denouncements and lurid descriptions of both the Mormon practice of polygamy and the intentions of the President and the Army in eastern newspapers led the Mormons to expect the worst. Young called up a militia of several thousand men to defend the territory and sent a small band to harass and delay the Army from entering the Territory. However, the early onset of winter forced the Army to camp in present-day Wyoming, allowing for negotiations between the Territory and the federal government. Poor planning, inadequate supplies for the Army, and the failure of the President to verify the reports of rebellion and to notify the territorial government of his intentions to replace Young led to widespread condemnation of Buchanan from Congress and the press, who labeled the war as "Buchanan's Blunder." When Young agreed to be replaced by Cumming and to allow the Army to enter the Utah Territory and establish a base, Buchanan attempted to save face by issuing proclamations detailing his merciful pardoning of the "rebels," which were poorly received by both Congress and the inhabitants of Utah. The troops, however, would soon be recalled to the East when a far greater national crisis erupted.

1860–1861: The nation disintegrates

When Republicans lost a plurality in the House in 1856, every significant bill they passed fell before Southern votes in the Senate or a Presidential veto. The Federal Government reached a stalemate. Bitter hostility between Republicans and Southern Democrats prevailed on the floor of Congress.

To make matters worse, Buchanan was dogged by the partisan Covode committee, which was investigating the administration for evidence of impeachable offenses.

Sectional strife rose to such a pitch in 1860 that the Democratic Party split. Buchanan played little part as the national convention meeting in Charleston, South Carolina deadlocked. The southern wing walked out of the Charleston convention and nominated its own candidate for the presidency, incumbent Vice President John C. Breckinridge, whom Buchanan refused to support. The remainder of the party finally nominated Buchanan's archenemy, Douglas. Consequently, when the Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln, it was a foregone conclusion that he would be elected even though his name appeared on no southern ballot. Buchanan watched silently as South Carolina seceded on December 20, followed by six other cotton states, and by February, they formed the Confederate States of America. Eight slave states refused to join.

In Buchanan's Message to Congress ( December 3, 1860), he denied the legal right of states to secede but held that the Federal Government legally could not prevent them. He hoped for compromise, but secessionist leaders did not want it.

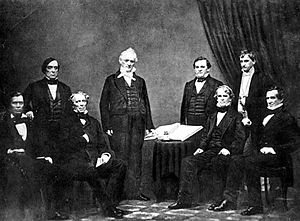

Beginning in late December, Buchanan reorganized his cabinet, ousting Confederate sympathizers and replacing them with hard-line nationalists Jeremiah S. Black, Edwin M. Stanton, Joseph Holt and John A. Dix. These conservative Democrats strongly believed in American nationalism and refused to countenance secession. At one point, Treasury Secretary Dix ordered Treasury agents in New Orleans, "If any man pulls down the American flag, shoot him on the spot".

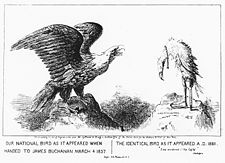

Before Buchanan left office, seven slave states seceded, the Confederacy was formed, all arsenals and forts in the seceded states were lost (except Fort Sumter and two remote ones), and a fourth of all federal soldiers surrendered to Texas troops. The government decided to hold on to Fort Sumter, which was located in Charleston, harbour, the most visible spot in the Confederacy. On January 5, Buchanan sent a civilian steamer Star of the West to carry reinforcements and supplies to Fort Sumter. On January 9, 1861, South Carolina state batteries opened fire on the Star of the West, which returned to New York. Paralyzed, Buchanan made no further moves to prepare for war.

On Buchanan's final day as president, he remarked to the incoming Lincoln, "If you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel on returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man."

Supreme Court appointments

Buchanan appointed the following Justice to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Nathan Clifford – 1858

States admitted to the Union

Post-presidency, death, and legacy

In 1866 Buchanan published Mr Buchanan's Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion — the first presidential memoir. He died June 1, 1868, at the age of 78 at his home at Wheatland. He was interred in Woodward Hill Cemetery in Lancaster. On the day before his death, he predicted that "history will vindicate my memory." Nevertheless, historians continue to emphasize his failure to deal with secession. The policy of appeasement practiced by Buchanan and his predecessor, Franklin Pierce, toward the pro-slavery lobby is often criticized. There is no evidence, however, that Pierce and Buchanan taking a harder line against slavery would have done anything but provoke the Southern states to secede a few years earlier than they eventually did. Whether America's slide toward secession during his administration was Buchanan's fault or whether it was simply his bad luck to have presided over it remains a matter for debate.

A bronze and granite memorial residing near the Southeast corner of Washington D.C.'s Meridian Hill Park was designed by architect William Gorden Beecher and sculpted by Maryland artist Hans Schuler. Commissioned in 1916, but not approved by the U.S. Congress until 1918, and not completed and unveiled until June 26, 1930, the memorial features a statue of Buchanan bookended by male and female classical figures representing law and diplomacy, with the engraved text reading: "The incorruptible statesman whose walk was upon the mountain ranges of the law," a quote from a member of Buchanan's cabinet, Jeremiah S. Black. The memorial in the nation's capital complemented an earlier monument, constructed in 1907–08 and dedicated in 1911, on the site of Buchanan's birthplace in StonyBatter, Pennsylvania. Part of an 18.5-acre memorial site, the monument is a 250-ton pyramid structure designed to show the original weathered surface of the native rubble and mortar.

An active Freemason during his lifetime, he was Master of Masonic Lodge #43 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and a District Deputy Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania.

Three counties are named in his honour: Buchanan County in Iowa, Missouri, and Virginia.

Historians in 2006 voted his failure to deal with secession the worst presidential mistake ever made. James Buchanan's average historical ranking by scholars considering presidential achievements, leadership qualities, failures and faults (such as corruption), place him as the second worst president in U.S. history.