Meander

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Geology and geophysics

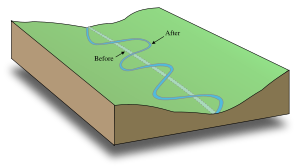

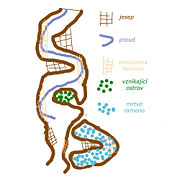

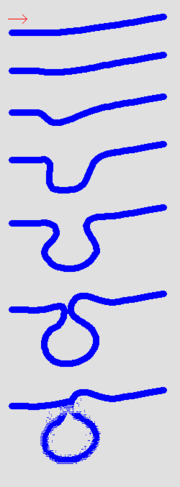

A meander in general is a bend in a sinuous watercourse, also known as an oxbow loop, or simply an oxbow. A stream of any volume may assume a meandering course, alternatively eroding sediments from the outside of a bend and depositing them on the inside. The result is a snaking pattern as the stream meanders back and forth across its down-valley axis. When a meander gets cut off from the main stream, an oxbow lake is formed. Over time meanders migrate downstream, sometimes in such a short time as to create civil engineering problems for local municipalities attempting to maintain stable roads and bridges.

There is not yet full consistency or standardization of scientific terminology used to describe watercourses. A variety of symbols and schemes exist. Parameters based on mathematical formulae or numerical data vary as well, depending on the database used by the theorist. Unless otherwise defined in a specific scheme "meandering" and "sinuosity" here are synonymous and mean any repetitious pattern of bends, or waveforms. In some schemes, "meandering" applies only to rivers with exaggerated circular loops or secondary meanders; that is, meanders on meanders.

Sinuosity is one of the channel types that a stream may assume over all or part of its course. All streams are sinuous at some time in their geologic history over some part of their length.

Origin of term

The term derives from the river known to the ancient Greeks as (Μαίανδρος) Maiandros or Maeander, characterised by a very convoluted path along the lower reach. As such, even in Classical Greece the name of the river had become a common noun meaning anything convoluted and winding, such as decorative patterns or speech and ideas, as well as the geomorphological feature. Strabo said: "... its course is so exceedingly winding that everything winding is called meandering."

The Meander River is located in present-day Turkey, south of Izmir, eastward the ancient Greek town of Miletus, now Turkish Milet. It flows through a graben in the Menderes Massif, but has a flood plain much wider than the meander zone in its lower reach. In the Turkish name, the Büyük Menderes River, Menderes is from Meander.

Meander geometry

The technical description of a meandering watercourse is termed meander geometry or meander planform geometry. It is characterized as an irregular waveform. Ideal waveforms, such as a sine wave, are one line thick, but in the case of a stream the width must be taken into consideration. The bankfull width is the distance across the bed at an average cross-section at the full-stream level, typically estimated by the line of lowest vegetation.

As a waveform the meandering stream follows the down-valley axis, a straight line fitted to the curve such that the sum of all the amplitudes measured from it is zero. This axis represents the overall direction of the stream.

At any cross-section the stream is following the sinuous axis, the centerline of the bed. Two consecutive crossing points of sinuous and down-valley axes define a meander loop. The meander is two consecutive loops pointing in opposite transverse directions. The distance of one meander along the down-valley axis is the meander length or wavelength. The maximum distance from the down-valley axis to the sinuous axis of a loop is the meander width or amplitude. The course at that point is the apex.

In contrast to sine waves, the loops of a meandering stream are more nearly circular. The curvature varies from a minimum at the apex to infinity at a crossing point (straight line), also called an inflection, because the curvature changes direction in that vicinity. The radius of the loop is considered to be the straight line perpendicular to the down-valley axis intersecting the sinuous axis at the apex. As the loop is not ideal additional information is needed to characterize it. The orientation angle is the angle between sinuous axis and down-valley axis at any point on the sinuous axis.

A loop at the apex has an outer or convex bank and an inner or concave bank. The meander belt is defined by an average meander width measured from outer bank to outer bank instead of from centerline to centerline. If there is a flood plain it extends beyond the meander belt. The meander is then said to be free - it can be found anywhere in the flood plain. If there is no flood plain the meanders are fixed.

Various mathematical formulae relate the variables of the meander geometry. As it turns out some numerical parameters can be established, which appear in the formulae. The waveform depends ultimately on the characteristics of the flow but the parameters are independent of it and apparently are caused by geologic factors. In general the meander length is 10-14 times, with an average 11 times, the fullbank channel width and 3 to 5 times, with an average of 4.7 times, the radius of curvature at the apex. This radius is 2-3 times the channel width.

A meander has a depth pattern as well. The cross-overs are marked by riffles, or shallow beds, while at the apices are pools. In a pool direction of flow is downward, scouring the bed material. The major volume, however, flows more slowly on the inside of the bend where, due to decreased velocity, it deposits sediment.

The line of maximum depth, or channel, is the thalweg or thalweg line. It is typically designated the borderline when rivers are used as political borders. The thalweg hugs the outer banks and returns to centre over the riffles. The meander arc length is the distance along the thalweg over one meander. The river length is the length along the centerline.

Formation

Meander formation is a somewhat equivocal term referring to the natural factors and processes that result in meanders. The waveform configuration of a stream is constantly changing. Once a sinusoidal channel exists it undergoes a process during which the amplitude and concavity of the loops increase dramatically due to the effect of helicoidal flow in increasing the amount of erosion occurring on the outside of a bend. In the words of Elizabeth A. Wood:

... this process of making meanders seems to be a self-intensifying process ... in which greater curvature results in more erosion of the bank, which results in greater curvature ...

The helical flow is explained as a transfer of momentum from the inside of the bend to the outside. As soon as the flow enters the bend some of its momentum becomes angular, the conservation of which would require an increase of velocity on the inside and a decrease on the outside, exactly the opposite of what happens. Instead centrifugal force superelevates the surface on the outside, moving surface water transversely into it. This water moves down to replace the subsurface water pushed back at the end of the bend. The result is the scouring helical flow, and the greater the curvature, the greater the angular momentum and the stronger the cross-current.

The question of formation is why streams of any size become sinuous in the first place. There are a number theories, not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Stochastic theory

The stochastic theory can take many forms but one of the most general statements is that of Scheidegger:

The meander train is assumed to be the result of the stochastic fluctuations of the direction of flow due to the random presence of direction-changing obstacles in the river path.

Given a flat, smooth, tilted artificial surface, rainfall runs off it in sheets, but even in that case adhesion of water to the surface and cohesion of drops produce rivulets at random. Natural surfaces are rough and erodable to different degrees. The result of all the physical factors acting at random is channels that are not straight, which then progressively become sinuous. Even channels that appear to be straight have a sinuous thalweg that leads eventually to a sinuous channel.

Equilibrium theory

In the equilibrium theory, meanders decrease the stream gradient until an equilibrium between the erodability of the terrain and the transport capacity of the stream is reached. A mass of water descending must give up potential energy, which, given the same velocity at the end of the drop as at the beginning, is removed by interaction with the material of the stream bed. The shortest distance; that is, a straight channel, results in the highest energy per unit of length, disrupting the banks more, creating more sediment and aggrading the stream. The presence of meanders allows the stream to adjust the length to an equilibrium energy per unit length in which the stream carries away all the sediment that it produces.

Geomorphic/Morphotectonic theory

Geomorphic refers to the surface structure of the terrain. Morphotectonic means having to do with the deeper, or tectonic (plate) structure of the rock. The features included under these categories are not random and guide streams into non-random paths. They are predictable obstacles that instigate meander formation by deflecting the stream. For example, a sandbar (geomorphic) might deflect the stream, causing or influencing a meander pattern, or the stream might be guided into a fault line (morphotectonic).

Associated landforms

Erosion Mechanics

Most meanders occur in the lower course of the river. Erosion is greater on the outside of the bend where velocity is greatest. Deposition of sediment occurs on the inner edge because the river, moving slowly, cannot carry its sediment load, creating a slip-off slope (Point Bars). The faster moving current on the outside bend has more erosive ability and the meander tends to grow in the direction of the outside bend, forming a river cliff. This can be seen in areas where willows grow on the banks of rivers; on the inside of meanders, willows are often far from the bank, whilst on the outside of the bend, the roots of the willows are often exposed and undercut, eventually leading the trees to fall into the river. This demonstrates the river's movement. Slumping usually occurs on the concave sides of the banks resulting in mass movements such as slides.

Deposits

Incised meanders

If the region later undergoes tectonic uplift, the meandering stream will again resume downward erosion. The meandering pattern will remain as a deep valley known as an incised meander. Rivers in the Colorado Plateau and streams in the Ozark Plateau are noted for these incised meanders. Incised meanders can also be formed when global falls in base level due to fall in sea levels.

Rincons

Sometimes an incised, also known as entrenched, meander is cut off. When it is, the resulting landform is called a rincon. They are created when a river erodes through the narrow neck of land between the ends of a loop, leaving the loop without an active cutting stream. One dramatic rincon on Lake Powell is called "The Rincon."

Scroll-bars

Scroll-bars are a result of continuous lateral migration of a meander loop that creates an asymmetrical ridge and swale topography on the inside of the bends. The topography generally parallel to the meander and is related to migrating bar forms and back bar chutes which carve sediment out from the outside of the curve and deposit sediment in the slower flowing water on the inside of the loop, in a process called lateral accretion. Scroll bar sediments are characterized by cross-bedding and a pattern of fining upward . These characteristics are a result of the dynamic river system, where larger grains are transported during high energy flood events and then gradually die down, depositing smaller material with time (Batty 2006). Deposits for meandering rivers are generally homogenous and laterally extensive unlike the more heterogenous braided river deposits There are two distinct patterns of scroll-bar depositions; the eddy accretion scroll bar pattern and the point-bar scroll pattern. When looking down the river valley they can be distinguished because the point-bar scroll patterns are convex and the eddy accretion scroll bar patterns are concave . Scroll bars often look lighter at the tops of the ridges and darker in the swales. This is because the tops can be shaped by wind, either adding fine grains or by keeping the area unvegetated, while the darkness in the swales can be attributed to silts and clays washing in in high water periods. This added sediment in addition to water that catches in the swales is in turn is a favorable environment for vegetation that will also accumulate in the swales.

Derived quantities

The meander ratio or sinuosity index is a means of quantifying how much a river or stream meanders (how much its course deviates from the shortest possible path). It is calculated as the length of the stream divided by the length of the valley. A perfectly straight river would have a meander ratio of 1 (it would be the same length as its valley), while the higher this ratio is above 1, the more the river meanders.

Sinuosity indices are calculated from the map or from an aerial photograph measured over a distance called the reach, which should be at least 20 times the average fullbank channel width. The length of the stream is measured by channel, or thalweg, length over the reach, while the bottom value of the ratio is the downvalley length or air distance of the stream between two points on it defining the reach.

The sinuosity index plays a part in mathematical descriptions of streams. The index may need to be elaborated because the valley may meander as well; i.e., the downvalley length is not identical to the reach. In that case the valley index is the meander ratio of the valley while the channel index is the meander ratio of the channel. The channel sinuosity index is the channel length divided by the valley length and the standard sinuosity index is the channel index divided by the valley index. Distinctions may become even more subtle.

Sinuosity Index has a non-mathematical utility as well. Streams can be placed in categories arranged by it; for example, when the index is between 1 to 1.5 the river is sinuous, but if between 1.5 and 4, then meandering. The index is a measure also of stream velocity and sediment load, those quantities being maximized at an index of 1 (straight).