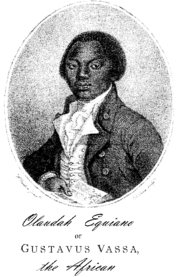

Olaudah Equiano

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Historical figures

Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745 – 31 March 1797), also known as Gustavus Vassa, was an eighteenth century merchant in the American colonies and in Britain. He was a leading influence in the abolition of slavery.

Biography

Early life and slavery

By his own account, Olaudah Equiano's early life began in the region of "Essaka" (in his spelling; now called Isseke) near the River Niger, an Igbo-speaking region of Nigeria, now in Anambra State. At an early age, he was kidnapped by kinsmen and forced into domestic slavery in another native village in a region where the African chieftain hierarchy was tied to slavery.

At the age of eleven, he was sold to white slave traders and taken to the New World. On arrival, he was bought by Michael Pascal, a lieutenant in the Royal Navy. Pascal renamed him Gustavus Vassa, renaming being a common practice among slave owners.

Being the slave of a naval captain, Equiano was afforded naval training and was able to travel extensively. He was sent to school in England by Pascal to learn to read. This was during the Seven Years War with France. Equiano was Pascal's personal servant but was also expected to contribute in times of battle. His duty was to haul gunpowder to the gun decks. After the war, Equiano felt he had done his duty and deserved his share of the prize money awarded to the other sailors, along with his freedom, but Pascal refused to grant it.

Later, Olaudah Equiano was sold on the island of Montserrat in the Caribbean Leeward Islands. Equiano's literacy and seamanship skills made him too valuable for plantation labour. He was acquired by Robert King, a Quaker merchant from Philadelphia who traded in the Caribbean. King set Equiano to work on his shipping routes and in his stores, promising him in 1765, that for forty pounds, the price King had paid for Equiano, he could buy his freedom. King taught him to read and write more fluently, educated him in the Christian faith, and allowed Equiano to engage in his own profitable trading as well as on his master's behalf, enabling Equiano to come by the forty pounds honestly. In his early twenties, Equiano succeeded in buying his freedom.

King urged Equiano to stay on as a business partner, but Equiano found it dangerous and limiting to remain in the British American colonies as a freed black. While loading a ship in Georgia, he was almost kidnapped back into slavery. Equiano returned to Britain, where slavery was much more limited.

In England, he received his wages from the Navy, but not from Pascal. He worked for a while as a hairdresser but the pay was not adequate, so he returned to working at sea.

Pioneer of the abolitionist cause

After several years of travels and trading, Equiano traveled to London and became involved in the abolitionist movement. The movement had been particularly strong amongst Quakers, but was by now non-denominational. Equiano himself was broadly Methodist, having been influenced by George Whitefield's evangelism in the New World.

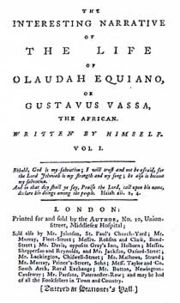

Olaudah Equiano proved to be a popular speaker and was introduced to many senior and influential people, who encouraged him to write and publish his life story. He was supported financially by philanthropic abolitionists and religious benefactors; his lectures and preparation for the book were promoted by, among others, Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. His account surprised many with the quality of its imagery and description, literary style, as well as its narrative which was profoundly shaming towards those who had not joined the abolitionist cause. Entitled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, it was first published in 1789 and rapidly went through several editions. It is one of the earliest known examples of published writing by an African writer. It was the first influential slave autobiography, and its first-hand account of slavery and of the experiences of an 18th-century black immigrant caused a sensation when published in 1789, fueling a growing anti-slavery movement in England and the USA.

Equiano's narrative begins in the West African village where he was kidnapped into slavery in 1756. He vividly recalls the pestilence and horror of the Middle Passage: "I now wished for the last friend, Death, to relieve me." As described in his book, the young Equiano was eventually shipped to a Virginia plantation where he witnessed slaves tortured with thumbscrews and the iron muzzle. Slavery, he explained, brutalizes everyone - the slaves, their overseers, plantation wives, and the whole of society.

The autobiography goes on to describe how Equiano's adventures brought him to London, where he married into English society and became a leading abolitionist. His exposé of the infamous slaver Zong - 133 slaves thrown overboard in mid-ocean for the insurance money - shook the nation. But it was Equiano's book that would prove his most lasting contribution to the abolitionist movement, a book which vividly demonstrated the humanity of Africans as much as the inhumanity of slavery.

The book not only furthered the abolitionist cause while providing an exemplary work of English literature by a new, African author, but also made Equiano's fortune. It gave him independence from his benefactors and enabled him to fully chart his own life and purpose, and develop his interest in working to improve economic, social and educational conditions in Africa, particularly in Sierra Leone.

Family in Britain

At some point, after having traveled widely, Olaudah Equiano appears to have decided to settle in Britain and raise a family. Equiano is closely associated with Soham, Cambridgeshire, where, on the 7 April 1792, he married Susannah Cullen, a local girl, in St Andrew's Church. He announced his wedding in every edition of his autobiography from 1792 onwards, and it has been suggested his marriage mirrored his anticipation of a commercial union between Africa and Great Britain. The couple settled in the area and had two daughters, Anna Maria , born October 16, 1793, and Joanna, born April 11, 1795.

Susannah died in February 1796 aged 34, and Equiano died a year after that on 31 March 1797, aged approximately 52. Soon after, the elder daughter died, aged four years old, leaving Joanna to inherit Equiano's estate, which was valued at £950: a considerable sum, worth approximately £100,000 today. Joanna married the Rev. Henry Bromley, and they ran a Congregational Chapel at Clavering near Saffron Walden in Essex, before moving to London in the middle of the nineteenth century - they are both buried at the Congregationalists' novel non-denominational Abney Park Cemetery, in Stoke Newington.

Last days and will

Although Equiano's death is recorded in London, the location of his burial is unknown. One of his last London addresses appears to have been Plaisters Hall in the City of London (from where he drew up his will on 28 May 1796).

Having drawn up his will, Olaudah Equiano moved to John Street, Tottenham Court Road, close to Whitefield's Methodist chapel (where there is a small, recent memorial); and lastly Paddington Street, Middlesex where he died. His death was reported in newspaper obituaries at the time, but seems not to have been widely known. He may have moved frequently and left an unclear trail to his burial place out of concerns for his safety and a desire to rest in peace. Factions of the political elite sought to suppress reformers and those linked to them in the 1790s, the time of the French Revolution and close on the heels of the American Revolution . In December 1797, unaware that he had died nine months earlier, the government-sponsored Anti-Jacobin, or Weekly Examiner presumed him to still be alive, for it satirised him at a fictional meeting of the Friends of Freedom.

Olaudah Equiano's will demonstrates the sincerity of his religious and social beliefs. Had his daughter Joanna died before reaching the age of inheritance (twenty-one), half his wealth would have passed to the Sierra Leone Company for the continued provision of assistance to West Africans, and half to the London Missionary Society, which promoted education overseas. This organisation had been formed the previous November at the Countess of Huntingdon's Spa Fields Chapel. By the early nineteenth century, The Missionary Society had become well known worldwide as non-denominational, though it was largely Congregational.

Modern views

Controversy of origin

Vincent Carretta, a professor of literature and author of Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man ( 2005), points out that a major problem facing any biographer is how to deal with Equiano's account of his origins.

As Carretta explains:

Equiano was certainly African by descent. The circumstantial evidence that Equiano was also African American by birth and African British by choice is compelling but not absolutely conclusive. Although the circumstantial evidence is not equivalent to proof, anyone dealing with Equiano's life and art must consider it.

This current doubt about his origins arises from records that suggest Equiano may have been born in South Carolina. Carretta suggests that there are baptismal records and a naval muster roll linking Equiano to South Carolina. Other academics have reported an oral history record of his upbringing, as he claimed, in Isske, Africa, principally based on Catherine Obianuju Acholonu's study: The Igbo Roots Of Olaudah Equiano: An Anthropological Research (1989). A more recent paper (June 2005) that favours Olaudah Equiano's own account of his African birth, is the Canadian academic study by Paul Lovejoy, Autobiography and Memory: Gustavus Vassa, alias Olaudah Equiano, the African.

Historians have never discredited the accuracy of Equiano's narrative, nor the power it had to support the abolitionist cause, particularly in Britain during the 1790s. However, parts of Equiano's account of the Middle Passage may have been based on already published accounts or the experiences of those he knew. It's possible that at one time he may have found it in his self-interest to lie by saying his birthplace was South Carolina. It could also have simply been a case of a language barrier. A further discussion of the arguments on this will be found at