Omega-3 fatty acid

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Health and medicine

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

|

| See also |

|

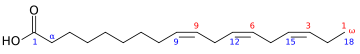

n−3 fatty acids (popularly referred to as ω−3 fatty acids or omega-3 fatty acids) are a family of unsaturated fatty acids that have in common a carbon–carbon double bond in the n−3 position; that is, the third bond from the methyl end of the fatty acid.

Important nutritionally essential n−3 fatty acids are: α-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The human body cannot synthesize n−3 fatty acids de novo, but it can form 20- and 22-carbon unsaturated n−3 fatty acids from the eighteen-carbon n−3 fatty acid, α-linolenic acid. These conversions occur competitively with n−6 fatty acids, which are essential closely related chemical analogues that are derived from linoleic acid. Both the n−3 α-linolenic acid and n−6 linoleic acid are essential nutrients which must be obtained from food. Synthesis of the longer n−3 fatty acids from linolenic acid within the body is competitively slowed by the n−6 analogues. Thus accumulation of long-chain n−3 fatty acids in tissues is more effective when they are obtained directly from food or when competing amounts of n−6 analogs do not greatly exceed the amounts of n−3.

Chemistry

The term n−3 (also called ω−3 or omega-3) signifies that the first double bond exists as the third carbon-carbon bond from the terminal methyl end (n) of the carbon chain.

n−3 fatty acids which are important in human nutrition are: α-linolenic acid (18:3, n−3; ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5, n−3; EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (22:6, n−3; DHA). These three polyunsaturates have either 3, 5 or 6 double bonds in a carbon chain of 18, 20 or 22 carbon atoms, respectively. All double bonds are in the cis-configuration, i.e. the two hydrogen atoms are on the same side of the double bond.

Most naturally-produced fatty acids (created or transformed in animalia or plant cells with an even number of carbon in chains) are in cis-configuration where they are more easily transformable. The trans-configuration results in much more stable chains that are very difficult to further break or transform, forming longer chains that aggregate in tissues and lacking the necessary hydrophilic properties. This trans-configuration can be the result of the transformation in alkaline solutions, or of the action of some bacterias that are shortening the carbonic chains. Natural transforms in vegetal or animal cells more rarely affect the last n−3 group itself. However, n−3 compounds are still more fragile than n−6 because the last double bond is geometrically and electrically more exposed, notably in the natural cis configuration.

List of n−3 fatty acids

This table lists several different names for the most common n−3 fatty acids found in nature.

| Common name | Lipid name | Chemical name |

|---|---|---|

| 16:3 (n−3) | all-cis-7,10,13-hexadecatrienoic acid | |

| α-Linolenic acid (ALA) | 18:3 (n−3) | all-cis-9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid |

| Stearidonic acid (STD) | 18:4 (n−3) | all-cis-6,9,12,15-octadecatetraenoic acid |

| Eicosatrienoic acid (ETE) | 20:3 (n−3) | all-cis-11,14,17-eicosatrienoic acid |

| Eicosatetraenoic acid (ETA) | 20:4 (n−3) | all-cis-8,11,14,17-eicosatetraenoic acid |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) | 20:5 (n−3) | all-cis-5,8,11,14,17-eicosapentaenoic acid |

| Docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), Clupanodonic acid |

22:5 (n−3) | all-cis-7,10,13,16,19-docosapentaenoic acid |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) | 22:6 (n−3) | all-cis-4,7,10,13,16,19-docosahexaenoic acid |

| Tetracosapentaenoic acid | 24:5 (n−3) | all-cis-9,12,15,18,21-docosahexaenoic acid |

| Tetracosahexaenoic acid (Nisinic acid) | 24:6 (n−3) | all-cis-6,9,12,15,18,21-tetracosenoic acid |

Biological significances

- The biological effects of the n−3 are largely mediated by their interactions with the n−6 fatty acids; see Essential fatty acid interactions for detail.

A 1992 article by biochemist William E.M. Lands provides an overview of the research into n−3 fatty acids, and is the basis of this section.

The 'essential' fatty acids were given their name when researchers found that they were essential to normal growth in young children and animals. (Note that the modern definition of ' essential' is more strict.) A small amount of n−3 in the diet (~1% of total calories) enabled normal growth, and increasing the amount had little to no additional benefit.

Likewise, researchers found that n−6 fatty acids (such as γ-linolenic acid and arachidonic acid) play a similar role in normal growth. However, they also found that n−6 was "better" at supporting dermal integrity, renal function, and parturition. These preliminary findings led researchers to concentrate their studies on n−6, and it was only in recent decades that n−3 has become of interest.

In 1963 it was discovered that the n−6 arachidonic acid was converted by the body into pro-inflammatory agents called prostaglandins. By 1979 more of what are now known as eicosanoids were discovered: thromboxanes, prostacyclins and the leukotrienes. The eicosanoids, which have important biological functions, typically have a short active lifetime in the body, starting with synthesis from fatty acids and ending with metabolism by enzymes. However, if the rate of synthesis exceeds the rate of metabolism, the excess eicosanoids may have deleterious effects. Researchers found that n−3 is also converted into eicosanoids, but at a much slower rate. Eicosanoids made from n−3 fats often have opposing functions to those made from n−6 fats (ie, anti-inflammatory rather than inflammatory). If both n−3 and n−6 are present, they will "compete" to be transformed, so the ratio of n−3:n−6 directly affects the type of eicosanoids that are produced.

This competition was recognized as important when it was found that thromboxane is a factor in the clumping of platelets, which leads to thrombosis. The leukotrienes were similarly found to be important in immune/inflammatory-system response, and therefore relevant to arthritis, lupus, and asthma. These discoveries led to greater interest in finding ways to control the synthesis of n−6 eicosanoids. The simplest way would be by consuming more n−3 and fewer n−6 fatty acids.

Health benefits

On September 8, 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration gave "qualified health claim" status to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) n−3 fatty acids, stating that "supportive but not conclusive research shows that consumption of EPA and DHA [n−3] fatty acids may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease." This updated and modified their health risk advice letter of 2001 (see below).

People with certain circulatory problems, such as varicose veins, benefit from fish oil. Fish oil stimulates blood circulation, increases the breakdown of fibrin, a compound involved in clot and scar formation, and additionally has been shown to reduce blood pressure. There is strong scientific evidence that n−3 fatty acids significantly reduce blood triglyceride levels and regular intake reduces the risk of secondary and primary heart attack.

Some benefits have been reported in conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and cardiac arrhythmias.

There is a promising preliminary evidence that n-3 fatty acids supplementation might be helpful in cases of depression and anxiety. Studies report highly significant improvement from n-3 fatty acids supplementation alone and in conjunction with medication.

Some research suggests that fish oil intake may reduce the risk of ischemic and thrombotic stroke. However, very large amounts may actually increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke (see below). Lower amounts are not related to this risk, and many studies used substantially higher doses without major side effects (for example: 4.4 grams EPA/2.2 grams DHA in 2003 study). No clear conclusion can be drawn at this time, however.

A 2006 report in the Journal of the American Medical Association concluded that their review of literature covering cohorts from many countries with a wide variety of demographic characteristics demonstrating a link between n−3 fatty acids and cancer prevention gave mixed results. This is similar to the findings of a review by the British Medical Journal of studies up to February 2002 that failed to find clear effects of long and shorter chain n−3 fats on total mortality, combined cardiovascular events and cancer.

In 1999, the GISSI-Prevenzione Investigators reported in the Lancet, the results of major clinical study in 11,324 patients with a recent myocardial infarction. Treatment 1 gram per day of n−3 fatty acids reduced the occurrence of death, cardiovascular death and sudden cardiac death by 20%, 30% and 45% respectively. These beneficial effects were seen already from three months onwards.

In April 2006, a team led by Lee Hooper at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK, published a review of almost 100 separate studies into n−3 fatty acids, found in abundance in oily fish. It concluded that they do not have a significant protective effect against cardiovascular disease. This meta-analysis was controversial and stands in stark contrast with two different reviews also performed in 2006 by the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition and a second JAMA review that both indicated decreases in total mortality and cardiovascular incidents (i.e. myocardial infarctions) associated with the regular consumption of fish and fish oil supplements. In addition n−3 has shown to aid in other mental disorders such as aggression and ADHD (Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder).

Several studies published in 2007 have been more positive. In the March 2007 edition of the journal Atherosclerosis, 81 Japanese men with unhealthy blood sugar levels were randomly assigned to receive 1800 mg daily of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA - an n−3 essential fatty acid from fish oil) with the other half being a control group. The thickness of the carotid arteries and certain measures of blood flow were measured before and after supplementation. This went on for approximately two years. A total of 60 patients (30 in the EPA group and 30 in the control group) completed the study. Those given the EPA had a statistically significant decrease in the thickness of the carotid arteries along with improvement in blood flow. The authors indicated that this was the first demonstration that administration of purified EPA improves the thickness of carotid arteries along with improving blood flow in patients with unhealthy blood sugar levels.

In another study published in the American Journal of Health System Pharmacy March 2007, patients with high triglycerides and poor coronary artery health were given 4 grams a day of a combination of EPA and DHA along with some monounsaturated fatty acids. Those patients with very unhealthy triglyceride levels (above 500 mg/dl) reduced their triglycerides on average 45% and their VLDL cholesterol by more than 50%. VLDL is a bad type of cholesterol and elevated triglycerides can also be deleterious for cardiovascular health.

There was another study published on the benefits of EPA in The Lancet in March 2007. This study involved over 18,000 patients with unhealthy cholesterol levels. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either 1,800 mg a day of EPA with a statin drug or a statin drug alone. The trial went on for a total of five years. It was found at the end of the study those patients in the EPA group had superior cardiovascular function. Non-fatal coronary events were also significantly reduced in the EPA group. The authors concluded that EPA is a promising treatment for prevention of major coronary events, especially non-fatal coronary events.

Another study regarding fish oil was published in the Journal of Nutrition in April 2007. Sixty four healthy Danish infants from nine to twelve months of age received either cow's milk or infant formula alone or with fish oil. It was found that those infants supplemented with fish oil had improvement in immune function maturation with no apparent reduction in immune activation.

There was yet another study on n−3 fatty acids published in the April 2007 Journal of Neuroscience. A group of mice were genetically modified to develop accumulation of amyloid and tau proteins in the brain similar to that seen in people with poor memory. The mice were divided into four groups with one group receiving a typical American diet (with high ratio of n−6 to n−3 fatty acids being 10 to 1). The other three groups were given food with a balanced 1 to 1 n−6 to n−3 ratio and two additional groups supplemented with DHA plus long chain n−6 fatty acids. After three months of feeding, all the DHA supplemented groups were noted to have a lower accumulation of beta amyloid and tau protein. Some research suggests that these abnormal proteins may contribute to the development of memory loss in later years.

There is also a study published regarding n−3 supplementation in children with learning and behavioural problems. This study was published in the April 2007 edition of the Journal of the Developmental and Behavioural Pediatrics (5), where 132 children, between the ages of seven to twelve years old, with poor learning, participated in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded interventional trial. A total of 104 children completed the trial. For the first fifteen weeks of this study, the children were given polyunsaturated fatty acids (n−3 and n−6, 3000 mg a day), polyunsaturated fatty acids plus multi-vitamins and minerals or placebo. After fifteen weeks, all groups crossed over to the polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) plus vitamins and mineral supplement. Parents were asked to rate their children's condition after fifteen and thirty weeks. After thirty weeks, parental ratings of behaviour improved significantly in nine out of fourteen scales. The lead author of the study, Dr. Sinn, indicated the present study is the largest PUFA trial to date with children falling in the poor learning and focus range. The results support those of other studies that have found improvement in poor developmental health with essential fatty acid supplementation.

Research in 2005 and 2006 has suggested that the in-vitro anti-inflammatory activity of n−3 acids translates into clinical benefits. Cohorts of neck pain patients and of rheumatoid arthritis sufferers have demonstrated benefits comparable to those receiving standard NSAIDs. Those who follow a Mediterranean-style diet tend to have less heart disease, higher HDL ("good") cholesterol levels and higher proportions of n−3 in tissue highly unsaturated fatty acids. Similar to those who follow a Mediterranean diet, Arctic-dwelling Inuit - who consume high amounts of n−3 fatty acids from fatty fish - also tend to have higher proportions of n−3, increased HDL cholesterol and decreased triglycerides (fatty material that circulates in the blood) and less heart disease. Eating walnuts (the ratio of n−3 to n−6 is circa 1:4 respectively) was reported to lower total cholesterol by 4% relative to controls when people also ate 27% less cholesterol.

A study examining whether omega-3 exerts neuroprotective action in Parkinson's disease found that it did, using an experimental model, exhibit a protective effect (much like it did for Alzheimer's disease as well). The scientists exposed mice to either a control or a high omega-3 diet from two to twelve months of age and then treated them with a neurotoxin commonly used as an experimental model for Parkinson's. The scientists found that high doses of omega-3 given to the experimental group completely prevented the neurotoxin-induced decrease of dopamine that ordinarily occurs. Since Parkinson's is a disease caused by disruption of the dopamine system, this protective effect exhibited could show promise for future research in the prevention of Parkinson's disease.

A study carried out involving 465 women showed serum levels of eicosapentaenoic acid is inversely related to the levels of anti-oxidized- LDL antibodies. Oxidative modification of LDL is thought to play an important role in the development of atherosclerosis.

In 2008 a German study suggested that Omega-3 fatty acids have a positive effect on atopic dermatitis

Health risks

In a letter published October 31, 2000, the United States Food and Drug Administration Centre for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Office of Nutritional Products, Labeling, and Dietary Supplements noted that known or suspected risks of EPA and DHA n−3 fatty acids may include the possibility of:

- Increased bleeding if overused (normally over 3 grams per day) by a patient who is also taking aspirin or warfarin. However, this is disputed.

- Hemorrhagic stroke (only in case of very large doses)

- Oxidation of n−3 fatty acids forming biologically active oxidation products.

- Reduced glycemic control among diabetics.

- Suppression of immune and inflammation responses, and consequently, decreased resistance to infections and increased susceptibility to opportunistic bacteria.

- An increase in concentration of LDL cholesterol in some individuals.

Subsequent advices from the FDA and national counterparts have permitted health claims associated with heart health.

Cardiac risk

Persons with congestive heart failure, chronic recurrent angina or evidence that their heart is receiving insufficient blood flow are advised to talk to their doctor before taking n−3 fatty acids. It may be prudent for such persons to avoid taking n−3 fatty acids or eating foods that contain them in substantial amounts.

In congestive heart failure, cells that are only barely receiving enough blood flow become electrically hyperexcitable. This, in turn, can lead to increased risk of irregular heartbeats, which, in turn, can cause sudden cardiac death. n−3 fatty acids seem to stabilize the rhythm of the heart by effectively preventing these hyperexcitable cells from functioning, thereby reducing the likelihood of irregular heartbeats and sudden cardiac death. For most people, this is obviously beneficial and would account for most of the large reduction in the likelihood of sudden cardiac death. Nevertheless, for people with congestive heart failure, the heart is barely pumping blood well enough to keep them alive. In these patients, n−3 fatty acids may eliminate enough of these few pumping cells that the heart would no longer be able to pump sufficient blood to live, causing an increased risk of cardiac death.

Research frontiers

Developmental differences

Essential fatty acid supplements have gained popularity for children with ADHD, autism, and other developmental differences. A 2004 Internet survey found that 29% of surveyed parents used essential fatty acid supplements to treat children with autism spectrum disorders.

Fish oils appear to reduce ADHD-related symptoms in some children. A 2007 double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of small groups of children found that omega-3 fatty acids reduced hyperactivity in children with autism spectrum disorders, Additional double blind studies have showed "medium to strong treatment effects of omega 3 fatty acids on symptoms of adhd.

Low birth weight

In a study of nearly 9,000 pregnant women, researchers found women who ate fish once a week during their first trimester had 3.6 times less risk of low birth weight and premature birth than those who ate no fish. Low consumption of fish was a strong risk factor for preterm delivery and low birth weight. However, attempts by other groups to reverse this increased risk by encouraging increased pre-natal consumption of fish were unsuccessful.

Psychiatric disorders

n−3 fatty acids are known to have membrane-enhancing capabilities in brain cells. One medical explanation is that n−3 fatty acids play a role in the fortification of the myelin sheaths. Not coincidentally, n−3 fatty acids comprise approximately eight percent of the average human brain according to Dr. David Horrobin, a pioneer in fatty acid research. Ralph Holman of the University of Minnesota, another major researcher in studying essential fatty acids, who gave Omega-3 its name, surmised how n−3 components are analogous to the human brain by stating that "DHA is structure, EPA is function."

A benefit of n−3 fatty acids is helping the brain to repair damage by promoting neuronal growth. In a six-month study involving people with schizophrenia and Huntington's disease who were treated with EPA or a placebo, the placebo group had clearly lost cerebral tissue, while the patients given the supplements had a significant increase of grey and white matter.

In the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of the brain, low brain n−3 fatty acids are thought to lower the dopaminergic neurotransmission in this brain area, possibly contributing to the negative and neurocognitive symptoms in schizophrenia. This reduction in dopamine system function in the PFC may lead to an overactivity in dopaminergic function in the limbic system of the brain which is suppressively controlled by the PFC dopamine system, causing the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. This is called the n−3 polyunsaturated fatty acid/dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia (Ohara, 2007). This mechanism may explain why n−3 supplementation shows effects against both positive, negative and neurocognitive symptoms in schizophrenia.

Consequently, the past decade of n−3 fatty acid research has procured some Western interest in n−3 fatty acids as being a legitimate 'brain food.' Still, recent claims that one's intelligence quotient, psychological tests measuring certain cognitive skills, including numerical and verbal reasoning skills, are increased on account of n−3 fatty acids consumed by pregnant mothers remain unreliable and controversial. An even more significant focus of research, however, lies in the role of n−3 fatty acids as a non-prescription treatment for certain psychiatric and mental diagnoses and has become a topic of much research and speculation.

In 1998, Andrew L. Stoll, MD and his colleagues at Harvard University conducted a small double-blind placebo-controlled study in thirty patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Most subjects in this study were already undergoing psychopharmacological treatment (e.g. 12 out of the 30 were taking lithium). Over the course of four months, he gave 15 subjects capsules containing olive oil, and another 15 subjects capsules containing nine grams of pharmaceutical-quality EPA and DHA. The study showed that subjects in the n−3 group were less likely to experience a relapse of symptoms in the four months of the study. Moreover, the n−3 group experienced significantly more recovery than the placebo group. However, a commentary on the Stoll study notes that the improvement in the n−3 group was too small to be clinically significant. Though Stoll believes that the 1999 experiment was not as optimal as it could have been and has accordingly pursued further research, the foundation has been laid for more researchers to explore the theoretical association between absorbed n−3 fatty acids and signal transduction inhibition in the brain.

"Several epidemiological studies suggest covariation between seafood consumption and rates of mood disorders. Biological marker studies indicate deficits in omega−3 fatty acids in people with depressive disorders, while several treatment studies indicate therapeutic benefits from omega-3 supplementation. A similar contribution of omega-3 fatty acids to coronary artery disease may explain the well-described links between coronary artery disease and depression. Deficits in omega-3 fatty acids have been identified as a contributing factor to mood disorders and offer a potential rational treatment approach." In 2004, a study found that 100 suicide attempt patients on average had significantly lower levels of EPA in their blood as compared to controls.

In 2006, a review of published trials in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that "the evidence available provides little support" for the use of fish or the n–3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids contained in them to improve depressed mood. The study used results of twelve randomized controlled trials in its meta-analysis. The review recommended that "larger trials with adequate power to detect clinically important benefits" be performed.

The n−6 to n−3 ratio

Clinical studies indicate that the ingested ratio of n−6 to n−3 (especially Linoleic vs Alpha Linolenic) fatty acids is important to maintaining cardiovascular health.

Both n−3 and n−6 fatty acids are essential, i.e. humans must consume them in the diet. n−3 and n−6 compete for the same metabolic enzymes, thus the n−6:n−3 ratio will significantly influence the ratio of the ensuing eicosanoids (hormones), (e.g. prostaglandins, leukotrienes, thromboxanes etc.), and will alter the body's metabolic function.Generally, grass-fed animals accumulate more n−3 than do grain-fed animals which accumulate relatively more n−6. Metabolites of n−6 are significantly more inflammatory (esp. arachidonic acid) than those of n−3. This necessitates that n−3 and n−6 be consumed in a balanced proportion; healthy ratios of n−6:n−3 range from 1:1 to 4:1. Studies suggest that the evolutionary human diet, rich in seafood and other sources of n−3, may have provided such a ratio.

Typical Western diets provide ratios of between 10:1 and 30:1 - i.e., dramatically skewed toward n−6. Here are the ratios of n−6 to n−3 fatty acids in some common oils: canola 2:1, soybean 7:1, olive 3–13:1, sunflower (no n−3), flax 1:3 cottonseed (almost no n−3), peanut (no n−3), grapeseed oil (almost no n−3) and corn oil 46 to 1 ratio of n−6 to n−3. It should be noted that olive, peanut and canola oils consist of approximately 80% monounsaturated fatty acids, (i.e. neither n−6 nor n−3) meaning that they contain relatively small amounts of n−3 and n−6 fatty acids. Consequently, the n−6 to n−3 ratios for these oils (i.e. olive, canola and peanut oils) are not as significant as they are for corn, soybean and sunflower oils.

Conversion efficiency of ALA to EPA and DHA

It has been reported that conversion of ALA to EPA and further to DHA in humans is limited, but varies with individuals. Women have higher ALA conversion efficiency than men, probably due to the lower rate of utilization of dietary ALA for beta-oxidation. This suggests that biological engineering of ALA conversion efficiency is possible. In the online book of The Benefits of Omega 3 Fatty Acids found in Seal Oil, as Opposed to Fish and Flaxseed Oils, Dr. Ho listed the several factors that inhibit the ALA conversion, which again indicate that the efficiency of ALA conversion could be adjusted by altering one's dietary habits, such as rebalancing the ratio of n−3 and n−6 fatty acid intake, restraining direct alcohol consumptions, and supplementing vitamins and minerals. However, Goyens et al. argues that it is the absolute amount of ALA, rather than the ratio of n−3 and n−6 fatty acids, which affects the conversion.