Tiktaalik

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Insects, Reptiles and Fish

| Tiktaalik Fossil range: Late Devonian |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

restoration of Tiktaalik roseae

|

||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||

| Tiktaalik roseae Daeschler, Shubin & Jenkins, 2006 |

Tiktaalik (pronounced /tɪkˈtaːlɪk/) is a genus of extinct sarcopterygian (lobe-finned) fish from the late Devonian period, with many features akin to those of tetrapods (four-legged animals). It is an example from several lines of ancient sarcopterygian fish developing adaptations to the oxygen-poor shallow-water habitats of its time, which led to the evolution of amphibians. Well-preserved fossils were found in 2004 on Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, Canada.

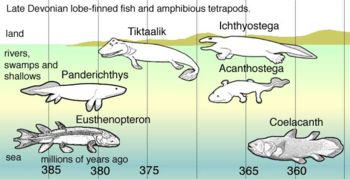

Tiktaalik lived approximately 375 million years ago. Paleontologists suggest that it was an intermediate form between fish such as Panderichthys, which lived about 380 million years ago, and early tetrapods such as Acanthostega and Ichthyostega, which lived about 365 million years ago. Its mixture of fish and tetrapod characteristics led one of its discoverers, Neil Shubin, to characterize Tiktaalik as a " fishapod" .

Description

Tiktaalik appears to be a transitional form between fish and amphibian. Unlike many previous, more fishlike transitional fossils, Tiktaalik's 'fins' have basic wrist bones and simple fingers, showing that they were weight bearing. Close examination of the joints show that although they probably were not used to walk, they were more than likely used to prop up the creature’s body, push up fashion. The bones of the fore fins show large muscle facets, suggesting that the fin was both muscular and had the ability to flex like a wrist joint. These wrist-like features were speculated to evolve, if not from land excursions, then as a useful adaptation to anchor the creature to the bottom in fast moving current.

A more robust ribcage is also a feature of Tiktaalik, which would have been very helpful in supporting the animal’s body if it did indeed venture from the water. Tiktaalik also lacked a characteristic that most fishes have - bony plates in the gill area that restrict lateral head movement. This means Tiktaalik is currently the earliest fish with a neck, which would give it more freedom in hunting prey either on land or in the shallows.

Also notable are the spiracles on the top of the head, which suggest the creature had primitive lungs as well as gills. This would have been useful in shallow water, where higher water temperature would lower oxygen content. This development may have led to the evolution of a more robust ribcage, a key evolutionary trait of land living creatures.

- Panderichthys, suited to muddy shallows;

- Tiktaalik with limb-like fins that could take it onto land;

- Early tetrapods in weed-filled swamps, such as:

- Acanthostega which had feet with eight digits,

- Ichthyostega with limbs.

Tiktaalik is a transitional fossil; it is to tetrapods what Archaeopteryx is to birds.

Its mixture of both fish and tetrapod characteristics include these traits:

- Fish

- fish gills

- fish scales

- "Fishapod"

- half-fish, half-tetrapod limb bones and joints, including a functional wrist joint and radiating, fish-like fins instead of toes

- half-fish, half-tetrapod ear region

- Tetrapod

- tetrapod rib bones

- tetrapod mobile neck

- tetrapod lungs

Tiktaalik generally had the characteristics of a lobe-finned fish, but with front fins featuring arm-like skeletal structures more akin to a crocodile, including a shoulder, elbow, and wrist. The rear fins and tail have not yet been found. It had rows of sharp teeth of a predator fish, and its neck was able to move independently of its body, which is not possible in other fish. The animal also had a flat skull resembling a crocodile's; eyes on top of its head, suggesting it spent a lot of time looking up; a neck and ribs similar to those of tetrapods, with the latter being used to support its body and aid in breathing via lungs; well developed jaws suitable for catching prey; and a small gill slit called a spiracle that, in more derived animals, became an ear .

The fossils were found in the " Fram Formation", deposits of meandering stream systems near the Devonian equator, suggesting a benthic animal that lived on the bottom of shallow waters and perhaps even out of the water for short periods, with a skeleton indicating that it could support its body under the force of gravity whether in very shallow water or on land . At that period, for the first time, deciduous plants were flourishing and annually shedding leaves into the water, attracting small prey into warm oxygen-poor shallows that were difficult for larger fish to swim in.. Neil Shubin and Ted Daeschler, the leaders of the team, have been searching Ellesmere Island for fossils since 1999. In an interview, Ted Daeschler stated that "we're making the hypothesis that this animal was specialized for living in shallow stream systems, perhaps swampy habitats, perhaps even to some of the ponds. And maybe occasionally, using its very specialized fins, for moving up overland. And that's what is particularly important here. The animal is developing features which will eventually allow animals to exploit land."

The name Tiktaalik is an Inuktitut word meaning " burbot", a freshwater fish related to true cod. The "fishapod" genus received this name after a suggestion by Inuit elders of Canada's Nunavut Territory, where the fossil was discovered .

Discovery

The three fossilized Tiktaalik skeletons were discovered in rock formed from late Devonian river sediments on Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, in northern Canada. At the time of the species' existence, Ellesmere Island was part of the Laurentia continent, which was centered on the equator and had a warm climate.

The remarkable find was made by a paleontologist who noticed the skull sticking out of a cliff. On further inspection, the ancient animal was found to be in fantastic shape for a 383-million-year-old specimen .

The discovery was published in the April 6, 2006 issue of Nature and quickly recognized as a classic example of a transitional form. Jennifer A. Clack, a Cambridge University expert on tetrapod evolution, said of Tiktaalik, "It's one of those things you can point to and say, 'I told you this would exist,' and there it is." According to a New Scientist article,

- "After five years of digging on Ellesmere Island, in the far north of Nunavut, they hit pay dirt: a collection of several fish so beautifully preserved that their skeletons were still intact. As Shubin's team studied the species they saw to their excitement that it was exactly the missing intermediate they were looking for. 'We found something that really split the difference right down the middle,' says Daeschler."