Trade and use of saffron

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Plants

Saffron has been used as a seasoning, fragrance, dye, and medicine for more than 3,000 years. The world's most expensive spice by weight, saffron consists of stigmas plucked from the saffron crocus (Crocus sativus). The resulting dried "threads" are distinguished by their bitter taste, hay-like fragrance, and slight metallic notes. Saffron is native to Southwest Asia, but was first cultivated in Greece. Iran is the world's largest producer of saffron, accounting for over half the total harvest.

In both antiquity and modern times, most saffron was and is used in the preparation of food and drink: cultures spread across Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas value the red threads for use in such items as baked goods, curries, and liquor. Medicinally, saffron was used in ancient times to treat a wide range of ailments, including stomach upsets, bubonic plague, and smallpox; clinical trials have shown saffron's potential as an anticancer and anti-aging agent. Saffron has been used to colour textiles and other items, many of which carry a religious or hierarchical significance.

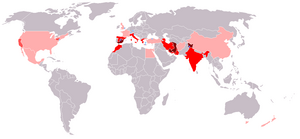

Saffron cultivation has long centred on a broad belt of Eurasia bounded by the Mediterranean Sea in the southwest to Kashmir and China in the northeast. The major saffron producers of antiquity—Iran, Spain, India, and Greece—continue to dominate the world trade. The cultivation of saffron in the Americas was begun by members of the Schwenkfelder Church in Pennsylvania. In recent decades cultivation has spread to New Zealand, Tasmania, and California.

Modern trade

Virtually all saffron is produced in a wide geographical belt extending from the Mediterranean in the west to Kashmir in the east. All continents outside this zone—except Antarctica—produce smaller amounts. Annual worldwide production amounts to some 300 tonnes, including whole threads and powder. This includes 50 tonnes of annual production of top-grade "coupe" saffron in 1991. Iran, Spain, India, Greece, Azerbaijan, Morocco, and Italy (in decreasing order of production) dominate the world saffron harvest, with Iran and Spain alone producing 80% of the world crop. Despite numerous cultivation efforts in such countries as Austria, England, Germany, and Switzerland, only select locales continue the harvest in Northern and Central Europe. Among these is the small Swiss village of Mund, in the Valais canton, whose annual saffron output comes to several kilograms. Micro-scale cultivation also occurs in Australia (in Tasmania), China, Egypt, France, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Turkey (particularly in the region surrounding Safranbolu, a city that took its name from saffron), the United States (especially in California and disproportionately by Iranian Americans) and Central Africa.

The high cost of saffron is due to the difficulty of manually extracting large numbers of minute stigmas; the only part of the crocus with the desired properties of aroma and flavour. In addition, a large number of flowers need to be processed in order to yield marketable amounts of saffron. A pound of dry saffron (0.45 kg) requires the harvesting of some 50,000 flowers, the equivalent of a football pitch's area of cultivation. By another estimate some 75,000 flowers are needed to produce one pound of dry saffron. This too depends on the average size of each saffron cultivar's stigmas. Another complication arises in the flowers' simultaneous and transient blooming. Since so many crocus flowers are needed to produce just one kilogram of dry saffron, about forty hours of intense labour, harvesting is often a frenetic affair. In Kashmir, for example, the thousands of growers must work continuously in relays over the span of one or two weeks throughout both day and night.

Once extracted, the stigmas must be dried quickly, lest decomposition or mould ruin the batch's marketability. The traditional method of drying involves spreading the fresh stigmas over screens of fine mesh, which are then baked over hot coals or wood or in oven-heated rooms with temperatures reaching 30–35 °C (86–95 °F) for 10–12 hours. Afterwards, the dried spice is preferably sealed in airtight glass containers. Bulk quantities of relatively lower-grade saffron can reach upwards of US$500/pound, while retail costs for small amounts may exceed 10 times that rate. In Western countries the average retail price is approximately $1,000 per pound, however. The high price is somewhat offset by the small quantities needed: a few grams at most in medicinal use and a few strands, at most, in culinary applications; there are between 70,000 and 200,000 strands in a pound.

Experienced saffron buyers often have rules of thumb when deliberating on their purchases. They may look for threads exhibiting a vivid crimson colouring, slight moistness, and elasticity. Meanwhile, they reject threads displaying telltale dull brick red colouring (indicative of age) and broken-off debris collected at the container's bottom (indicative of age-related brittle dryness). Such aged samples are most likely encountered around the main June harvest season, when retailers attempt to clear out the previous season's old inventory and make room for the new season’s crop. Indeed, experienced buyers recommend that only the current season's threads should be used at all. Thus, reputable saffron wholesalers and retailers will indicate the year of harvest or the two years that bracket the harvest date; a late 2002 harvest would be shown as "2002/2003".

Culinary use

Saffron is used extensively in Indian, Arab, Central Asian, European, Iranian, and Moroccan cuisines. Its aroma is described by cooking experts and saffronologists as resembling that of honey, with grassy, hay-like, and metallic notes. Saffron's taste is like that of hay, but with hints of bitter. Saffron also contributes a luminous yellow-orange colouring to items it is soaked with. For these traits saffron is used in baked goods, cheeses, confectionaries, curries, liquors, meat dishes, and soups. Saffron is used in India, Iran, Spain, and other countries as a condiment for rice. Saffron rice is used in many cuisines such as the cuisine of Spain. It is used in its many famous dishes such as paella valenciana, which is a spicy rice-meat preparation, and the zarzuela fish stews. It is also used in fabada asturiana. Saffron is essential in making the French bouillabaisse, which is a spicy fish stew from Marseilles, the Italian risotto alla milanese, and the Cornish saffron bun.

Iranians use saffron in their national dish, chelow kabab, while Uzbeks use it in a special rice dish known as a "wedding plov" (cf. pilaf). Moroccans use it in their tajine-prepared dishes, including kefta ( meatballs with tomato), mqualli (a citron-chicken dish), and mrouzia (succulent lamb dressed with plums and almonds). Saffron is also central in chermoula herb mixture, which flavours many Moroccan dishes. Indian cuisine uses saffron in its biryanis, which are spicy rice-vegetable dishes. (An example is the Pakki variety of Hyderabadi biryani.) It is also used in Indian milk-based sweets such as gulab jamun, kulfi, double ka meetha, and "saffron lassi", which is a spicy Jodhpuri yogurt-based drink.

Because of its high cost, saffron was often replaced by or diluted with safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) or turmeric (Curcuma longa) in cuisine. Both mimic saffron's colour well, but have flavours very different from that of saffron. Saffron is also used in the confectionery and liquor industries; this is its most common use in Italy. Chartreuse, izarra, and strega are types of alcoholic beverages that rely on saffron to provide a flourish of colour and flavour.

Experienced saffron users often crumble and pre-soak threads for several minutes prior to adding them to their dishes. For example, they may toss threads into water or sherry and leave them to soak for approximately ten minutes. This process extracts the threads' colour and flavour into the liquid phase; powdered saffron does not require this step. Afterward, the soaking solution is added to the hot and cooking dish. This allows even distribution of saffron's colour and flavour throughout a dish, and is important when preparing baked goods or thick sauces.

Medicinal use

Saffron's folkloric uses as an herbal medicine are legendary. It was used for its carminative (suppressing cramps and flatulence) and emmenagogic (enhancing pelvic blood flow) properties. Medieval Europeans used saffron to treat respiratory infections and disorders such as coughs and common colds, scarlet fever, smallpox, cancer, hypoxia, and asthma. Other targets included blood disorders, insomnia, paralysis, heart diseases, flatulence, stomach upsets and disorders, gout, chronic uterine haemorrhage, dysmorrhea, amenorrhea (absence of menstrual period), baby colic, and eye disorders. For ancient Persians and Egyptians, saffron was also an aphrodisiac, a general-use antidote against poisoning, a digestive stimulant, and a tonic for dysentery and measles. In Europe practitioners of the archaic "Doctrine of Signatures" took saffron's yellowish hue as a sign of its supposed curative properties against jaundice.

Initial research suggests that carotenoids present in saffron are anticarcinogenic (cancer-suppressing), anti-mutagenic (mutation-preventing), and immunomodulatory properties. Dimethylcrocetin, the compound responsible for these effects, counters a wide range of murine ( rodent) tumours and human leukaemia cell lines. Saffron extract also delays ascites tumour growth, delays papilloma carcinogenesis, inhibits squamous cell carcinoma, and decreases soft tissue sarcoma incidence in treated mice. Researchers theorise that, based on the results of thymidine-uptake studies, such anticancer activity is best attributed to dimethylcrocetin's disruption of the DNA-binding ability of a class of enzymes known as type II topoisomerases. As topoisomerases play a key role in managing DNA topology, the malignant cells are less successful in synthesizing or replicating their own DNA.

Saffron's pharmacological effects on malignant tumours have been documented in studies done both in vitro and in vivo. For example, saffron extends the lives of mice that are intraperitoneally impregnated with transplanted sarcomas, namely, samples of S-180, Dalton's lymphoma ascites (DLA), and Ehrlich ascites carcinoma (EAC) tumours. Researchers followed this by orally administering 200 mg of saffron extract per each kg of mouse body weight. As a result the life spans of the tumour-bearing mice were extended to 111.0%, 83.5%, and 112.5%, respectively, in relation to baseline spans. Researchers also discovered that saffron extract exhibits cytotoxicity in relation to DLA, EAC, P38B, and S-180 tumour cell lines cultured in vitro. Thus, saffron has shown promise as a new and alternative treatment for a variety of cancers.

Besides wound-healing and anticancer properties, saffron is also an antioxidant. This means that, as an "anti-aging" agent, it neutralises free radicals. Specifically, methanol extractions of saffron neutralise at high rates the DPPH (IUPAC nomenclature: 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) radicals. This occurred via vigorous proton donation to DPPH by two of saffron's active agents, safranal and crocin. Thus, at concentrations of 500 and 1000 ppm, crocin studies showed neutralisation of 50% and 65% of radicals, respectively. Safranal displayed a lesser rate of radical neutralisation than crocin, however. Such properties give saffron extracts promise as an ingredient for use as an antioxidant in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and as a food supplement. Ingested at high enough doses, however, saffron is lethal. Several studies done on lab animals have shown that saffron's LD50 (median lethal dose, or the dose at which 50% of test animals die from overdose) is 20.7 g/kg when delivered via a decoction.

Colouring and perfumery

| Saffron | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hex triplet | #F4C430 | |

| B | ( r, g, b) | (244, 196, 48) |

| HSV | ( h, s, v) | (45°, 80%, 96%) |

| Source | BF2S Colour Guide | |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) |

||

Despite its high cost, saffron has been used as a fabric dye, particularly in China and India. It is an unstable colouring agent; the vibrant orange-yellow hue that it imparts to clothing quickly fades to a pale and creamy yellow. The saffron stamens, even when used in minute quantities, produce a luminous yellow-orange colour. Increasing the amount of saffron applied will turn the fabric's imparted colour an increasingly rich shade of red. Traditionally, clothing dyed with saffron was reserved for the noble classes, implying that saffron played a ritualised and caste-representative role. Saffron dye is responsible for the saffron, vermilion, and ochre hues of the distinctive mantles and robes worn by Hindu and Buddhist monks. In medieval Ireland and Scotland, well-to-do monks wore a long linen undershirt known as a léine; it was traditionally dyed with saffron. In histology, the hematoxylin- phloxine-saffron (HPS) stain is used as a tissue stain to make biological structures more visible under a microscope.

There have been many attempts to replace costly saffron with a cheaper dye. Saffron's usual substitutes in food—turmeric, safflower, and other spices—yield a bright yellowish hue that does not precisely match that of saffron. Nevertheless, saffron's main colour-yielding constituent, the flavonoid crocin, has been discovered in the gardenia fruit. Because gardenia is much less expensive to cultivate than saffron, it is currently being researched in China as an economical saffron-dye substitute.

In Europe, saffron threads were a key component of an aromatic oil known as crocinum, which comprised such ingredients as alkanet, dragon's blood (for colour), and wine (for colour). Crocinum was applied as a perfume to hair. Another preparation involved mixing saffron with wine to produce a viscous yellow spray that was copiously applied to Roman theatres as an air freshener.

Citations

- ^ Deo 2003, p. 1.

- ^ Grigg 1974, p. 287.

- ^ a b c Hill 2001, p. 272.

- ^ a b McGee 2004, p. 422.

- ^ a b Katzer 2001.

- ^ Goyns 1999, p. 2.

- ^ Courtney 2002.

- ^ a b c Abdullaev 2002, p. 1.

- ^ Hill 2004, p. 273.

- ^ Rau 1969, p. 35.

- ^ Lak 1998.

- ^ Goyns 1999, p. 8.

- ^ Hill 2004, p. 274.

- ^ a b Hill 2004, p. 275.

- ^ Goyns 1999, p. 59.

- ^ Willard 2001, p. 203.

- ^ Park 2005.

- ^ Abdullaev 2002, p. 2.

- ^ Darling Biomedical Library 2002.

- ^ Hasegawa, Kurumboor & Nair 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Nair, Pannikar & Panikkar 1991, p. 1.

- ^ Assimopoulou 2005, p. 1.

- ^ Chang, Kuo & Wang 1964, p. 1.

- ^ Willard 2001, p. 205.

- ^ Major 1892, p. 49.

- ^ Dharmananda 2005.

- ^ Dalby 2002, p. 138.