Medicine for the Invisible Wounds of the Children of Aceh

26/12/2005

By Carola Vogl from Meulaboh (West Aceh)

Eti* is scared of rain. When the wind whistles through the tin roofs, she curls up in a corner of her wooden hut, shaking. She hasn’t been back to the beach to play with her friends like she did on 26 December a year ago. Nothing has been the same since.

Eti does not remember much of that day when she was playing with her sister near her father's fishing boat after he had come back from the sea after a long night of fishing.

Somebody screamed, "Air naik!", ‘the water is coming at us!’. They had no time to run away. The last thing she remembers is the huge black wave which swallowed her, thrashed her about like clothes in a washing machine, and then spat her out one and a half kilometres inland, completely naked and covered in scratches, but otherwise unharmed. Eti's sister had similar luck; she also survived the tsunami with only minor injuries. Her father did not. No one has seen the 34-year-old man since the morning of 26 December, though Eti and her sister still pray every day to Allah that He bring their father back to them one day.

"The children were especially affected by the tsunami. Many died in the flood, and those that survived saw the unimaginable. They lost their parents and their best friends. Many of the children are severely traumatised; they are scared of rain, storms and wind. They relive this day in their dreams again and again; they dream of the dirty water that washed them away, of the ruins, of the stench," says Yudi Kartiwa, SOS Children's Villages project director for the West Aceh region.

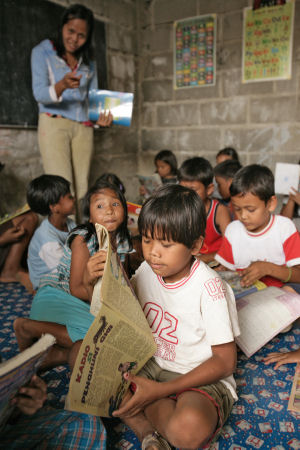

"When we arrived here in January 2005 everything was torn apart. There were no more schools, no distractions, no fun, only devastation and mourning. We saw that there was a need for a special psycho-social programme for the surviving children in addition to the reconstruction of houses and infrastructure. This is how 'Play and Learn' came about. We went to the emergency shelters every day together with psychologists from the organisation Ibu4Aceh and played and sang with the children, had them draw pictures and write poetry, in order to express themselves and share their feelings about what they had experienced. They were also given English, maths and Koran lessons, to give them back a bit of school routine and stimulate their minds," says Kartiwa as she describes their work in these exceptional circumstances.

A wooden hut hardly bigger than a shed, with little benches and a blackboard and barely enough space for the children's group in the refugee camp, is what the people there, themselves needy, built out of the remains of their homes. The grounds in front of the hut serve as a playground and are used for teaching as well.

Eti and her friends from the wooden shacks hold hands. They form a small circle together with two young psychologists from the Ibu4Aceh team. They sing a song that is often played on the radio in Aceh, called Wate Na Geumpa, or "When the big earthquake comes". The words of the song prepare them, in a playful manner, for what should be done in the case of an emergency. The tectonic plates are always rubbing together in this part of the world and no one here believes that the earthquake in November will be the last. "When the big earthquake comes we will remain calm. We will leave our home together and run to the mountains. We will be prepared and have a flashlight, water and a blanket ready. When the big earthquake comes we will know what to do. And when the sea pulls back, we will not go fishing, but will sit on a high place and calmly wait until it is safe again. Then we will go back."

Fitriana Herarti is a psychologist and leads the psycho-social programme of Ibu4Aceh in Melaboh, West Aceh. Ibu means "mother" in Indonesian, and the name is supposed to express what the organisation offers to the people in the crisis region: help regardless of religion and skin colour. The committed young woman explains the principles underlying her work with the children in the emergency shacks: "We first have to win the trust of the children. Only when they trust us can they believe that we can help them, and they will share their feelings and their pain with us. When the children finally do open up and tell the others in a group about what they have experienced, we remain in the background. We encourage the children to console and advise each other, and in this way find solutions to their problems themselves. They all share a similar fate, only it is easier for some of them to deal with it than others, they have no more nightmares and dreams. That gives the other children hope."

In treating a case of trauma, so-called trauma intervention, Fitriana and her co-workers are very cautious: "Many children are still very afraid of the sea. With these children we go to the beach. We let them look at the sea from the safety of the car and tell them that it does not only bring destruction, but that it can also be calm and harmless. The following week we go to the beach again and some of us get out and play ball. The children are free to get out of the car and play with us or to watch the others play from the car. Whatever they decide, we do not leave them alone. Bit by bit and week by week, their fears decrease, and limits are overcome. A child may panic and break out in a sweat upon seeing the sea, and a few weeks later, in the best of cases, the child will be happily playing ball with us and his or her friends. I do not believe that time heals all wounds, as is often said. If someone has experienced a trauma, intervention is required if the wound is to heal."

Eti is lucky again. The psychologists will work at healing her trauma; they will help her overcome her fears step by step and free herself of the agonising nightmares. Eti knows another song that she and the other children from the wooden huts learned from the psychologists. It has a funny name, a word the children had never heard before: trauma. The words are simple and the children understand them well: "Let's talk about our grief, about our anger and our silence. Do not hide your pain and do not feel guilty, talk about it until it heals; that is the medicine for the wound left behind by the trauma."

*Name changed to protect the child’s identity

This article is part of the tsunami one year on review.