Wars of the Roses

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: British History 1500 and before (including Roman Britain); Military History and War

|

|||||

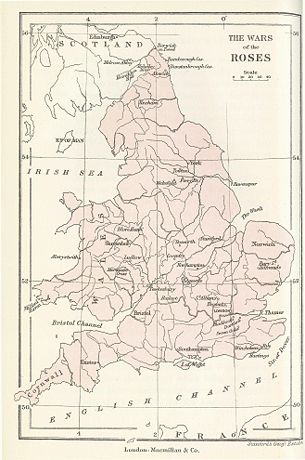

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487) were a series of dynastic civil wars fought in England between supporters of the Houses of Lancaster and York. Although armed clashes had occurred previously between supporters of Lancastrian King Henry VI and Richard, Duke of York, head of the rival House of York, the first open fighting broke out in 1455 and resumed more violently in 1459. Henry was captured and Richard became Protector of England, but was dissuaded from claiming the throne. Inspired by Henry's Queen, Margaret of Anjou, the Lancastrians resumed the conflict, and Richard was killed in battle at the end of 1460. His eldest son was proclaimed King Edward IV after a crushing victory at the Battle of Towton early in 1461.

After several years of minor Lancastrian revolts, Edward fell out with his chief supporter and advisor, the Earl of Warwick (known as the "Kingmaker"), who tried first to supplant him with his jealous younger brother George, and then to restore Henry VI to the throne. This resulted in two years of rapid changes of fortune, before Edward IV once again won a complete victory in 1471. Warwick and the Lancastrian heir Edward, Prince of Wales died in battle and Henry was murdered immediately afterwards.

A period of comparative peace followed, but Edward died unexpectedly in 1483. His surviving brother Richard of Gloucester first moved to prevent Edward's widow Queen Elizabeth's unpopular family from participating in government during the minority of Edward's son, Edward V, and then seized the throne for himself, using the suspect legitimacy of Edward IV's marriage as pretext. This provoked several revolts, and Henry Tudor, a distant relative of the Lancastrian kings who had nevertheless inherited their claim, overcame and killed Richard in battle at Bosworth in 1485.

Yorkist revolts flared up in 1487, resulting in the last pitched battles. Sporadic rebellions continued to take place until the last (and fraudulent) Yorkist pretender was executed in 1499.

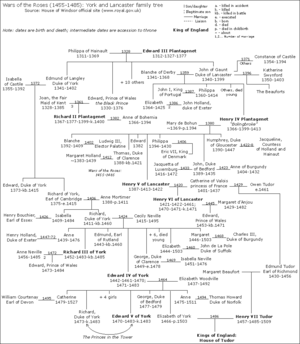

Fought largely by the landed aristocracy and armies of feudal retainers, support for each house largely depended upon dynastic factors, such as marriages within the nobility, feudal titles, and tenures. It is sometimes difficult to follow the shifts of power and allegiance because nobles acquired or lost titles through marriage, confiscation or attainture. For example, the Lancastrian patriarch John of Gaunt's first title was Earl of Richmond, the same title which Henry VII later held, while the Yorkist patriarch Edmund of Langley's first title was Earl of Cambridge. However it was not uncommon for nobles to switch sides and several battles were decided by treachery.

Name and symbols

The name "Wars of the Roses" is not thought to have been used during the time of the wars but has its origins in the badges associated with the two royal houses, the Red Rose of Lancaster and the White Rose of York. The term came into common use in the nineteenth century, after the publication of Anne of Geierstein by Sir Walter Scott. Scott based the name on a fictional scene in William Shakespeare's play Henry VI Part 1, where the opposing sides pick their different-coloured roses at the Temple Church.

Although the roses were occasionally used as symbols during the wars, most of the participants wore badges associated with their immediate feudal lords or protectors. For example, Henry's forces at Bosworth fought under the banner of a red dragon, while the Yorkist army used Richard III's personal symbol of a white boar. Evidence of the importance of the rose symbols at the time, however, includes the fact that King Henry VII chose at the end of the wars to combine the red and white roses into a single red and white Tudor Rose.

The unofficial system of livery and maintenance, by which powerful nobles would offer protection to followers who would sport their colours and badges (livery), and controlled large numbers of paid men-at-arms (maintenance) was one of the effects of the breakdown of royal authority which preceded and partly caused the wars.

Disputed succession

The antagonism between the two houses started with the overthrow of King Richard II by his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Lancaster, in 1399. As an issue of Edward III's third son John of Gaunt, Bolingbroke had a very poor claim to the throne. According to precedent, the crown should have passed to the male descendants of Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence, Edward III's second son, and in fact, the childless Richard II had named Lionel's grandson, Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March as heir presumptive. However, Richard II was then deposed and Bolingbroke was crowned as Henry IV. He was tolerated as king since Richard II's government had been highly unpopular. Nevertheless, within a few years of taking the throne, Henry found himself facing several rebellions in Wales, Cheshire and Northumberland, which used the Mortimer claim to the throne both as pretext and rallying point. All these revolts were suppressed, although with difficulty.

Henry IV died in 1413. His son and successor, Henry V, inherited a temporarily pacified nation. Henry was a great soldier, and his military success against France in the Hundred Years' War bolstered his enormous popularity, enabling him to strengthen the Lancastrian hold on the throne.

Henry V's short reign saw one conspiracy against him, the Southampton Plot led by Richard, Earl of Cambridge, a son of Edmund of Langley, the fifth son of Edward III. Cambridge was executed in 1415 for treason at the start of the campaign leading up to the Battle of Agincourt. Cambridge's wife, Anne Mortimer, also had a claim to the throne, being the daughter of Roger Mortimer and thus a descendant of Lionel of Antwerp. Richard, Duke of York, the son of Cambridge and Anne Mortimer was four years old at the time of his father's death. With his titles and inheritance restored, he grew up to put forward his parents' claims to the throne as head of the House of York, which believed that it had a stronger claim to the throne than the Lancastrian kings.

Henry VI

Henry V died unexpectedly in 1422, and the Lancastrian King Henry VI of England ascended the throne as an infant only nine months old. After the death of his uncle, John, Duke of Bedford in 1435, he was surrounded by unpopular regents and advisors. In addition to Henry's surviving paternal uncle, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, the most notable of these were Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset and William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, who were blamed for mismanaging the government and poorly executing the continuing Hundred Years' War with France. Under Henry VI, virtually all English holdings in France, including the land won by Henry V, were lost.

Suffolk eventually succeeded in having Humphrey of Gloucester arrested for treason. Humphrey died while awaiting trial in 1447. However, with severe reverses in France, Suffolk was stripped of office and murdered on his way to exile. Somerset succeeded him as leader of the party seeking peace with France. Richard, Duke of York, meanwhile represented those who wished to prosecute the war more vigorously, and criticised the court for starving him of funds and men during his campaigns in France. In all these quarrels, Henry VI had taken little part. He was portrayed as a weak, ineffectual king. In addition, he suffered from episodes of mental illness that he may have inherited from his grandfather Charles VI of France. By the 1450s many considered Henry incapable of carrying out the duties and responsibilities of a king.

The increasing discord at court was mirrored in the country as a whole, where noble families engaged in private feuds and showed increasing disrespect for the royal authority and for the courts of law. The Percy-Neville feud was the best-known of these private wars, but others were being conducted freely. In many cases they were fought between old-established families, and formerly minor nobility raised in power and influence by Henry IV in the aftermath of the rebellions against him. The quarrel between the Percys, for long the Earls of Northumberland, and the comparatively upstart Nevilles was one which followed this pattern; another was the feud between the Courtenays and Bonvilles in Cornwall and Devonshire. A factor in these feuds was apparently the presence of large numbers of soldiers discharged from the English armies that had been defeated in France. Nobles engaged many of these to mount raids, or to pack courts of justice with their supporters, intimidating suitors, witnesses and judges.

This growing civil discontent, the abundance of feuding nobles with private armies, and corruption in Henry VI's court formed a political climate ripe for civil war. With the king so easily manipulated, power rested with those closest to him at court, in other words Somerset and the Lancastrian faction. As a result Richard and the Yorkist faction, who tended to be physically placed further away from the seat of power, found their power slowly being stripped away. Royal power also started to slip, as Henry was convinced to gift more of his land to the Lancastrians.

In 1453, Henry suffered the first of several bouts of complete mental collapse, during which he failed even to recognise his new-born son, Edward of Westminster. A Council of Regency was set up, headed by the Duke of York, who still remained popular with the people, as Lord Protector. Richard soon asserted his power with ever-greater boldness (although there is no proof that he had aspirations to the throne at this early stage). Believing the Lancastrians to be undermining the nation, he imprisoned Somerset and backed his Neville allies (his brother-in-law, the Earl of Salisbury, and Salisbury's son, the Earl of Warwick), in their continuing feud with the Earl of Northumberland, a powerful supporter of Henry.

Henry recovered in 1455 and once again fell under the influence of those closest to him at court. Directed by Henry's queen, the powerful and aggressive Margaret of Anjou, who emerged as the de facto leader of the Lancastrians, Richard was forced out of court. Margaret built up an alliance against Richard and conspired with other nobles to reduce his influence. An increasingly thwarted Richard (who feared arrest for treason) finally resorted to armed hostilities in 1455 at the First Battle of St Albans.

Initial phase 1455–60

Richard, Duke of York led a small force toward London and was met by Henry's forces at St Albans, north of London, on May 22, 1455. The relatively small First Battle of St Albans was the first open conflict of the civil war. Richard's aim was ostensibly to remove "poor advisors" from King Henry's side. The result was a Lancastrian defeat. Several prominent Lancastrian leaders, including Somerset and Northumberland, were killed. After the battle, the Yorkists found Henry sitting quietly in his tent, abandoned by his advisors and servants, apparently having suffered another bout of mental illness. York and his allies regained their position of influence, and for a while both sides seemed shocked that an actual battle had been fought and did their best to reconcile their differences. With the king indisposed, York was again appointed Protector, and Margaret was shunted aside, charged with the king's care.

After the first Battle of St Albans, the compromise of 1455 enjoyed some success, with York remaining the dominant voice on the Council even after Henry's recovery. The problems which had caused conflict soon re-emerged, particularly the issue of whether the Duke of York, or Henry and Margaret's infant son, Edward, would succeed to the throne. Margaret refused to accept any solution that would disinherit her son, and it became clear that she would only tolerate the situation for as long as the Duke of York and his allies retained the military ascendancy.

In 1456, Henry went on royal progress in the Midlands, where the king and queen were popular. Margaret did not allow him to return to London where the merchants were angry at the decline in trade and widespread disorder. The king's court was set up at Coventry. By then, the new Duke of Somerset was emerging as a favourite of the royal court. Margaret also persuaded Henry to dismiss the appointments York had made as Protector, while York was made to return to his post as lieutenant in Ireland. Disorder in the capital and piracy on the south coast were growing, but the king and queen remained intent on protecting their own positions, with the queen introducing conscription for the first time in England. Meanwhile, York's ally, Warwick (later dubbed "The Kingmaker"), was growing in popularity in London as the champion of the merchants.

Following York's unauthorised return from Ireland, hostilities resumed. On September 23, 1459, at the Battle of Blore Heath in Staffordshire, a large Lancastrian army failed to prevent a Yorkist force under the Earl of Salisbury from marching from Middleham Castle in Yorkshire to link up with York at Ludlow Castle. Shortly afterwards the combined Yorkist armies confronted the much larger Lancastrian force at the Battle of Ludford Bridge. One of Warwick's lieutenants defected to the Lancastrians, and the Yorkist leaders fled; York fled back to Ireland, and Edward, Earl of March (York's eldest son, later Edward IV of England), Salisbury, and Warwick fled to Calais. The Lancastrians were back in total control, and Somerset was sent off to be Governor of Calais. His attempts to evict Warwick were easily repulsed, and the Yorkists even began to launch raids on the English coast from Calais in 1459–60, adding to the sense of chaos and disorder.

In 1460, Warwick and the others launched an invasion of England and rapidly established themselves in Kent and London, where they enjoyed wide support. Backed by a papal emissary who had taken their side, they marched north. Henry led an army south to meet them while Margaret remained in the north with Prince Edward. The Battle of Northampton on July 10, 1460, proved disastrous for the Lancastrians, and aided by treachery in the king's ranks, the Yorkist army under the Earl of Warwick was able to defeat the Lancastrians. Following the battle, and for the second time in the war, King Henry was found by the Yorkists abandoned by his retinue in a tent. He had apparently suffered another breakdown. With the king in their possession, the Yorkists returned to London.

Act of Accord

In the light of this military success, Richard moved to press his claim to the throne based on the illegitimacy of the Lancastrian line. Landing in north Wales, he and his wife Cecily entered London with all the ceremony usually reserved for a monarch. Parliament was assembled, and when York entered he made straight for the throne, which he may have been expecting the Lords to encourage him to take for himself as they had Henry IV in 1399. Instead, there was stunned silence. He announced his claim to the throne, but the Lords, even Warwick and Salisbury, were shocked by his presumption; they had no desire at this stage to overthrow King Henry. Their ambition was still limited to the removal of his bad councilors.

The next day, York produced detailed genealogies to support his claim based on his descent from Lionel of Antwerp and was met with more understanding. Parliament agreed to consider the matter and accepted that York's claim was better, but by a majority of five, they voted that Henry VI should remain as king. A compromise was struck in October 1460 with the Act of Accord, which recognised York as Henry's successor, disinheriting Henry's six year old son, Edward. York accepted this compromise as the best on offer. It gave him much of what he wanted, particularly since he was also made Protector of the Realm and was able to govern in Henry's name. Margaret was ordered out of London with Prince Edward. The Act of Accord proved unacceptable to the Lancastrians, who rallied to Margaret, forming a large army in the north.

Lancastrian counter-attack

The Duke of York left London later that year with the Earl of Salisbury to consolidate his position in the north against Margaret's army, reported to be massing near the city of York. Richard took up a defensive position at Sandal Castle near Wakefield at Christmas 1460. Although outnumbered by more than two to one, Richard's forces left the castle, attacked, and suffered a devastating defeat at the Battle of Wakefield on December 30. Richard was slain in the battle, and both Salisbury and Richard's 17-year-old second son, Edmund, Earl of Rutland, were captured and beheaded. Margaret ordered the heads of all three placed on the gates of York. This event, or the later defeat of Richard III, later inspired the mnemonic "Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain" for the seven colours of the rainbow.

The Act of Accord and the events of Wakefield left the 18-year-old Edward, Earl of March, York's eldest son, as Duke of York and heir to the throne. Salisbury's death left Warwick, his heir, as the biggest landowner in England. Margaret travelled to Scotland to negotiate for Scottish assistance. Mary of Gueldres, Queen of Scotland agreed to give Margaret an army on condition that she cede the town of Berwick to Scotland and Mary's daughter be betrothed to Prince Edward. Margaret agreed, although she had no funds to pay her army and could only promise booty from the riches of southern England, as long as no looting took place north of the River Trent. She took her army to Hull, recruiting more men as she went.

Edward of York meanwhile, with an army from the pro-Yorkist Marches (the border area between England and Wales), met the Earl of Pembroke's army arriving from Wales, and he defeated them soundly at the Battle of Mortimer's Cross in Herefordshire. He inspired his men with a "vision" of three suns at dawn (a phenomenon known as " parhelion"), telling them that it was a portent of victory and represented the three surviving York sons; himself, George and Richard. This led to Edward's later adoption of the sign of the sunne in splendour as his personal emblem.

Margaret was moving south, wreaking havoc as she progressed, her army supporting itself by looting as it passed through the prosperous south of England. In London, Warwick used this as propaganda to reinforce Yorkist support throughout the south — the town of Coventry switched allegiance to the Yorkists. Warwick failed to start raising an army soon enough and, without Edward's army to reinforce him, was caught off-guard by the Lancastrians' early arrival at St Albans. At the Second Battle of St Albans the Queen won the Lancastrians' most decisive victory yet, and as the Yorkist forces fled they left behind King Henry, who was found unharmed, sitting quietly beneath a tree.

Henry knighted thirty Lancastrian soldiers immediately after the battle. In an illustration of the increasing bitterness of the war, Queen Margaret instructed her seven-year-old son Edward of Westminster, to determine the manner of execution of the Yorkist knights who had been charged with keeping Henry safe and had stayed at his side throughout the battle.

As the Lancastrian army advanced southwards, a wave of dread swept London, where rumours were rife about savage northerners intent on plundering the city. The people of London shut the city gates and refused to supply food to the queen's army, which was looting the surrounding counties of Hertfordshire and Middlesex.

Yorkist triumph

Meanwhile, Edward advanced towards London from the west where he had joined forces with Warwick. This coincided with the northward retreat by the queen to Dunstable, allowing Edward and Warwick to enter London with their army. They were welcomed with enthusiasm, money and supplies by the largely Yorkist-supporting city. Edward could no longer claim simply to be trying to wrest the king from bad councillors; it had become a battle for the crown. Edward needed authority, and this seemed forthcoming when the Bishop of London asked the people of London their opinion and they replied with shouts of "King Edward". This was quickly confirmed by Parliament, and Edward was unofficially crowned in a hastily arranged ceremony at Westminster Abbey amidst much jubilation, although Edward vowed he would not have a formal coronation until Henry and Margaret were executed or exiled. He also announced that Henry had forfeited his right to the crown by allowing his queen to take up arms against his rightful heirs under the Act of Accord, though it was being widely argued that Edward's victory was simply a restoration of the rightful heir to the throne, which neither Henry nor his Lancastrian predecessors had been. It was this argument which Parliament had accepted the year before.

Edward and Warwick marched north, gathering a large army as they went, and met an equally impressive Lancastrian army at Towton. The Battle of Towton, near York, was the biggest battle of the Wars of the Roses thus far. Both sides agreed beforehand that the issue was to be settled that day, with no quarter asked or given. An estimated 40,000—80,000 men took part, with over 20,000 men being killed during (and after) the battle, an enormous number for the time and the greatest recorded single day's loss of life on English soil. Edward and his army won a decisive victory, the Lancastrians were routed, with most of their leaders slain. Henry and Margaret, who were waiting in York with their son Edward, fled north when they heard the outcome. Many of the surviving Lancastrian nobles switched allegiance to King Edward, and those who did not were driven back to the northern border areas and a few castles in Wales. Edward advanced to take York where he was confronted with the rotting heads of his father, his brother and Salisbury, which were replaced with those of defeated Lancastrian lords such as the notorious John Clifford, 9th Baron de Clifford of Skipton-Craven, who was blamed for the execution of Edward's brother Edmund, Earl of Rutland, after the Battle of Wakefield.

Henry and Margaret fled to Scotland where they stayed with the court of James III, implementing their earlier promise to cede Berwick to Scotland and leading an invasion of Carlisle later in the year. But lacking money, they were easily repulsed by Edward's men who were rooting out the remaining Lancastrian forces in the northern counties.

Edward IV

Edward IV's official coronation took place in June 1461 in London where he received a rapturous welcome from his supporters. Edward was able to rule in relative peace for ten years.

In the north, Edward could never really claim to have complete control until 1464, as apart from rebellions, several castles with their Lancastrian commanders held out for years. Dunstanburgh, Alnwick (the Percy family seat), and Bamburgh were some of the last to fall. The last to surrender was the fortress of Harlech (Wales) in 1468, after a seven-year-long siege.

There were two Lancastrian revolts in the north in 1464. Several Lancastrian nobles, including the Duke of Somerset, who had apparently been reconciled to Edward, readily led the rebellion. The first clash was at the Battle of Hedgeley Moor on April 25 and the second at the Battle of Hexham on May 15. Both revolts were put down by Warwick's brother, John Neville, 1st Marquess of Montagu. Somerset was captured and executed after the defeat at Hexham. The deposed King Henry was also captured in 1465 and held prisoner at the Tower of London where, for the time being, he was reasonably well treated.

Resumption of hostilities 1469–71

The period 1467–70 marked a rapid deterioration in the relationship between King Edward and his former mentor, the powerful Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick — "the Kingmaker". This had several causes but stemmed originally from Edward's decision to marry Elizabeth Woodville in secret in 1464. Edward later announced the news of his marriage as fait accompli, to the considerable embarrassment of Warwick, who had been negotiating a match between Edward and a French bride, convinced as he was of the need for an alliance with France. This embarrassment turned to bitterness when the Woodvilles came to be favoured over the Nevilles at court. Other factors compounded Warwick's disillusionment: Edward's preference for an alliance with Burgundy (over France), and Edward's reluctance to allow his brothers George, Duke of Clarence, and Richard, Duke of Gloucester, to marry Warwick's daughters, Isabel Neville and Anne Neville, respectively. Furthermore, Edward's general popularity was on the wane in this period with higher taxes and persistent disruptions of law and order.

By 1469 Warwick had formed an alliance with Edward's jealous and treacherous brother George. They raised an army which defeated the king at the Battle of Edgecote Moor and held Edward at Middleham Castle in Yorkshire. (Warwick briefly had two Kings of England in his custody.) Warwick had the queen's father, Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers, executed. He forced Edward to summon a parliament at York at which it was planned that Edward would be declared illegitimate, and the crown would thus pass to George, Duke of Clarence as Edward's heir apparent. However, the country was in turmoil, and Edward was able to call on the loyalty of his brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and the majority of the nobles. Richard arrived at the head of a large force and liberated King Edward.

Warwick and Clarence were declared traitors and forced to flee to France, where in 1470 Louis XI of France was coming under pressure from the exiled Margaret of Anjou to help her invade England and regain her captive husband's throne. It was King Louis who suggested the idea of an alliance between Warwick and Margaret, a notion which neither of the old enemies would at first entertain but eventually came round to, realising the potential benefits. However, both were undoubtedly hoping for different outcomes: Warwick for a puppet king in the form of Henry or his young son; Margaret to be able to reclaim her family's realm. In any case, a marriage was arranged between Warwick's daughter Anne Neville and Margaret's son, the former Prince of Wales, Edward of Westminster, and Warwick invaded England in the autumn of 1470.

This time it was Edward IV who was forced to flee the country when John Neville changed loyalties to support his brother Warwick. Edward was unprepared for the arrival of Neville's large force from the north and had to order his army to scatter. Edward and Gloucester fled from Doncaster to the coast and thence to Holland and exile in Burgundy. Warwick had already invaded from France, and his plans to liberate and restore Henry VI to the throne came quickly to fruition. Henry VI was paraded through the streets of London as the restored king in October and Edward and Richard were proclaimed traitors. Warwick's success was short-lived, however. He overreached himself with his plan to invade Burgundy in alliance with the King of France, tempted by King Louis' promise of territory in the Netherlands as a reward. This led Charles the Bold of Burgundy to assist Edward (who was also his brother in law), providing funds and an army to launch an invasion of England in 1471.

Edward landed with a small force at Ravenspur on the Yorkshire coast. He soon gained the city of York and rallied several supporters. His brother Clarence turned traitor again, abandoning Warwick. Having captured London, Edward's army met Warwick's at the Battle of Barnet. The battle was fought in thick fog, and some of Warwick's men attacked each other by mistake. It was believed by all that they had been betrayed, and Warwick's army fled. Warwick was cut down trying to reach his horse.

Margaret and her son Edward had landed in the West Country only a few days before the Battle of Barnet. Rather than return to France, Margaret sought to join with the Lancastrian supporters in Wales and marched to cross the Severn but was thwarted when the city of Gloucester refused her passage across the river. Her army, commanded by the fourth successive Duke of Somerset, was brought to battle and destroyed at the Battle of Tewkesbury, and Prince Edward of Westminster, the Lancastrian heir to the throne, was killed. With no heirs to succeed him, Henry VI was murdered shortly afterwards on May 14, 1471, to strengthen the Yorkist hold on the throne.

Richard III

The restoration of Edward IV in 1471 is sometimes seen as marking the end of the Wars of the Roses. Peace was restored for the remainder of Edward's reign, but when he died suddenly in 1483, political and dynastic turmoil erupted again. Under Edward IV, frictions had developed between the queen's Woodville relatives ( Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers and Thomas Grey, 1st Marquess of Dorset) and others who resented the Woodvilles' new-found status at court and saw them as power-hungry upstarts and parvenus. At the time of Edward's premature death, his heir, Edward V, was only 12 years old. The Woodvilles were in a position to influence the young king's future government, since Edward V had been brought up under the stewardship of Earl Rivers in Ludlow. This was too much for many of the anti-Woodville faction to accept, and in the struggle for the protectorship of the young king and control of the council, Edward IV's brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who had been named by Edward IV on his deathbed as Protector of England, came to be de facto leader of the anti-Woodville faction.

With the help of William Hastings and Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, Gloucester captured the young king from the Woodvilles at Stony Stratford in Buckinghamshire. Thereafter Edward V was kept under Gloucester's custody in the Tower of London, where he was later joined by his younger brother, the 9-year-old Richard, Duke of York. Having secured the boys, Richard then alleged that Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville had been illegal and that the two boys were therefore illegitimate. Parliament agreed and enacted the Titulus Regius, which officially named Gloucester as King Richard III. The two imprisoned boys, known as the " Princes in the Tower", disappeared and were possibly murdered; by whom and under whose orders remains controversial.

Since Richard was the finest general on the Yorkist side, many accepted him as a ruler better able to keep the Yorkists in power than a boy who would have had to rule through a committee of regents. However, many had never been reconciled to Yorkist rule, and within the Yorkist faction itself, some influential former allies of Richard turned against him. Richard himself had Lord Hastings, one of his brother Edward's closest companions and supporters, arrested and executed for treason. This may have been intended to thwart a genuine conspiracy, but the effect was to make many nobles fear for their own safety and to distrust Richard.

One former Yorkist, the Duke of Buckingham (who himself had a distant claim to the throne), led a revolt aimed at installing the Lancastrian Henry Tudor. It was defeated, and Buckingham was captured and executed. This was clearly not the end of the plots against Richard, who could never again feel secure, and who also suffered the loss of his wife and infant son, putting the future of the Yorkist dynasty in doubt.

Henry Tudor

Lancastrian hopes centred on Henry Tudor, whose father, Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond, had been a half-brother of Henry VI. However, Henry's claim to the throne was through his mother, Margaret Beaufort, a descendant of Edward III, derived from John Beaufort, a grandson of Edward III's as the son of John of Gaunt (illegitimate at birth though later legitimized by the marriage of his parents).

Henry Tudor landed in Pembrokeshire in the summer of 1485 and, gathering supporters on his march through Wales, defeated Richard at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Richard was slain during the battle by the powerful Welsh knight Rhys ap Thomas, with a blow to the head from his pollaxe, and Henry became King Henry VII of England. Henry then strengthened his position by marrying Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV and the best surviving Yorkist claimant. He thus reunited the two royal houses, merging the rival symbols of the red and white roses into the new emblem of the red and white Tudor Rose. Henry shored up his position by executing all other possible claimants whenever any excuse was offered, a policy his son, Henry VIII, continued.

Many historians consider the accession of Henry VII to mark the end of the Wars of the Roses. Others argue that the Wars of the Roses concluded only with the Battle of Stoke in 1487, which arose from the appearance of a pretender to the throne, a boy named Lambert Simnel who bore a close physical resemblance to the young Earl of Warwick, the best surviving male claimant of the House of York. The pretender's plan was doomed from the start, because the young earl was still alive and in King Henry's custody. At Stoke, Henry defeated forces led by John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, who had been named by Richard III as his heir but had been reconciled with Henry after Bosworth, thus effectively removing the remaining Yorkist opposition. Simnel was pardoned for his part in the rebellion and was sent to work in the royal kitchens. Henry's throne was again challenged with the appearance of the pretender Perkin Warbeck who in 1491 claimed to be Richard, Duke of York (the younger of the two Princes in the Tower). Henry consolidated his power in 1499 with the capture and execution of Warbeck.

Aftermath

Although historians still debate the true extent of the conflict's impact on medieval English life, there is little doubt that the Wars of the Roses resulted in political upheaval and changes to the established balance of power. The most obvious effect was the collapse of the Plantagenet dynasty and its replacement with the new Tudor rulers who changed England dramatically over the following years. In the following Henrician and post-Henrician times, the remnant Plantagenet factions with no direct line to the throne were disabused of their independent positions, as monarchs continually played them against each other.

With their heavy casualties among the nobility coupled with the effects of the Black Death, the wars are thought to have ushered in a period of great social upheaval in feudal England, including a weakening of the feudal power of the nobles and a corresponding strengthening of the merchant classes, and the growth of a strong, centralized monarchy under the Tudors. It heralded the end of the medieval period in England and the movement towards the Renaissance.

On the other hand, it has also been suggested that the traumatic impact of the wars was exaggerated by Henry VII to magnify his achievement in quelling them and bringing peace. Certainly, the effect of the wars on the merchant and labouring classes was far less than in the long drawn-out wars of siege and pillage in France and elsewhere in Europe, carried out by mercenaries who profited from the prolonging of the war. Although there were some lengthy sieges, such as at Harlech Castle and Bamburgh Castle, these were in comparatively remote and sparsely-inhabited regions. In the populated areas, both factions had much to lose by the ruin of the country and sought quick resolution of the conflict by pitched battle.

The war was disastrous for England's already declining influence in France, and by the end of the struggle few of the gains made over the course of the Hundred Years' War remained, apart from Calais which eventually fell during the reign of Queen Mary. Although later English rulers continued to campaign on the continent, England's territories were never reclaimed. Indeed, various duchies and kingdoms in Europe played a pivotal role in the outcome of the war; in particular the kings of France and the dukes of Burgundy played the two factions off each other, pledging military and financial aid and offering asylum to defeated nobles to prevent a strong and unified England making war on them.

The post-war period was also the death knell for the large standing baronial armies, which had helped fuel the conflict. Henry, wary of any further fighting, kept the barons on a very tight leash, removing their right to raise, arm, and supply armies of retainers so that they could not make war on each other or the king. England did not have another standing army until Cromwell's New Model Army. As a result the military power of individual barons declined, and the Tudor court became a place where baronial squabbles were decided with the influence of the monarch.

In fiction

Shakespeare's plays on Henry VI, parts 1, 2, and 3, and his Richard III cover the period of the wars. Henry VI, Part 1 includes a scene in the Temple church where the dispute between the two houses begins, giving the conflict its modern name:

"And here I prophesy: this brawl today,

Grown to this faction in the Temple garden,

Shall send, between the Red Rose and the White,

A thousand souls to death and deadly night."

— Warwick, Henry VI, Part One

- The four Shakespeare plays were memorably combined in a single massive landmark compendium by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1963 titled The War of the Roses directed by Peter Hall.

- Sir Walter Scott's Anne of Geierstein concerns exiled English Lancastrians in 15th century Burgundy and Switzerland.

- Robert Louis Stevenson's The Black Arrow is set during the war; the hero is a young Yorkist nobleman.

- The video game Yu-Gi-Oh! The Duelists of the Roses is loosely based on the war, with the protagonists of the series taking the role of the Lancastrians and the antagonists acting as the Yorkists.

- The fantasy novel series by George R. R. Martin titled A Song of Ice and Fire is loosely based on the War of the Roses, with the Starks modeled after the York family and the Lannisters modeled after the Lancaster.

- The historical novel by Sharon Kay Penman titled The Sunne in Splendour is based on the Wars of the Roses, and more specifically on the life of Richard III.

- Referred to in THE WARRIOR HEIR, which provides the break between the two parties (White & Red roses)

- Blackadder I is set during and after the Battle of Bosworth field, with a fictional outcome of the battle

Key figures

- Kings of England

- Henry VI (Lancastrian)

- Edward IV (Yorkist)

- Edward V (Yorkist)

- Richard III (Yorkist)

- Henry VII (Tudor)

- Prominent antagonists 1455–87

- Yorkist

- Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York

- Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick ('The Kingmaker')

- Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury

- John Neville, 1st Marquess of Montagu

- William Neville, 1st Earl of Kent

- Bastard of Fauconberg

- Lancastrian

- Margaret of Anjou Queen to Henry VI

- Sir Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland

- Henry Percy, 3rd Earl of Northumberland

- Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick ('The Kingmaker')

- Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset

- Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of Somerset

- Edmund Beaufort, 4th Duke of Somerset

- George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence

- Yorkist

- Earl of Pembroke

- Lord Clifford

Battles

- First Battle of St Albans: May 22, 1455 (Yorkist victory)

- Battle of Blore Heath: September 23, 1459 (Yorkist victory)

- Battle of Ludford Bridge: October 12, 1459 (Lancastrian victory)

- Battle of Northampton (1460): July 10, 1460 (Yorkist victory)

- Battle of Wakefield: December 30, 1460 (Lancastrian victory)

- Battle of Mortimer's Cross: February 2, 1461 (Yorkist victory)

- Second Battle of St Albans: February 22, 1461 (Lancastrian victory)

- Battle of Ferrybridge: March 28, 1461 (Indecisive)

- Battle of Towton: March 29, 1461 (Yorkist victory)

- Battle of Hedgeley Moor: April 25, 1464 (Yorkist victory)

- Battle of Hexham: May 15, 1464 (Yorkist victory)

- Battle of Edgecote Moor: July 26, 1469 (Lancastrian victory)

- Battle of Lose-coat Field: March 12, 1470 (Yorkist victory)

- Battle of Barnet: April 14, 1471 (Yorkist victory)

- Battle of Tewkesbury: May 4, 1471 (Yorkist victory)

- Battle of Bosworth Field: August 22, 1485 (Lancastrian victory)

- Battle of Stoke Field: June 16, 1487 (Lancastrian victory)