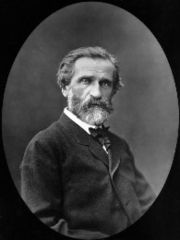

Giuseppe Verdi

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Performers and composers; Poetry & Opera

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (pronounced [dʒuˈzɛpːe ˈverdi] in Italian; October 9 or 10, 1813 – January 27, 1901) was an Italian Romantic composer, mainly of opera. He was one of the most influential composers of Italian opera in the 19th century. His works are frequently performed in opera houses throughout the world and, transcending the boundaries of the genre, some of his themes have long since taken root in popular culture - such as " La donna è mobile" from Rigoletto, " Va, pensiero" (The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves) from Nabucco, and " Libiamo ne' lieti calici" (The Drinking Song) from La traviata. Although his work was sometimes criticized for using a generally diatonic rather than a chromatic musical idiom and having a tendency toward melodrama, Verdi’s masterworks dominate the standard repertoire a century and a half after their composition.

Biography

Verdi was born in Le Roncole, a village near Busseto, then in the Département Taro which was a part of the French Empire after the annexation of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza. The baptismal register, on 11 October, lists him as being "born yesterday", but since days were often considered to begin at sunset, this could have meant either 9 or 10 October. The next day he was baptized in the Roman Catholic church in Latin as Joseph Fortuninus Franciscus. The day after that (Tuesday), Carlo Giuseppe Verdi (Verdi's father) took his new born the three miles to Busseto to register him. The baby was recorded as Joseph Fortunin Francois; the clerk wrote in French. "So it happened that for the civil and temporal world Verdi was born a Frenchman." When he was still a child, Verdi's parents moved from Piacenza to Busseto, where the future composer's education was greatly facilitated by visits to the large library belonging to the local Jesuit school. Also in Busseto, Verdi was given his first lessons in composition.

Verdi went to Milan when he was twenty to continue his studies and he took private lessons in counterpoint while attending operatic performances , as well as concerts of, specifically, German music. Milan's beaumonde association convinced him that he should pursue a career as a theatre composer.

Returning to Busseto, he became town music master and, with the support of Antonio Barezzi, a local merchant and music lover who had long supported Verdi's musical ambitions in Milan, Verdi gave his first public performance at Barezzi’s home in 1830. Because he loved Verdi’s music, Barezzi invited Verdi to be his daughter Margherita's music teacher and the two soon fell deeply in love. They were married in 1836 and Margherita gave birth to two children, both of whom died in infancy, followed by Margherita herself in 1840. Verdi adored his wife and children, and he was devastated when they all died in the prime of youth. During the mid 1830s he attended the "Salotto Maffei" salons in Milan, hosted by Clara Maffei.

Initial recognition

The production of his first opera, Oberto, by Milan's La Scala, achieved a degree of success, after which Bartolomeo Merelli, an impresario with La Scala, offered Verdi a contract for two more works.

It was while he worked on his second opera, Un giorno di regno, that Verdi's wife and children died. The opera was a flop, and he fell into despair vowing to give up musical composition forever. However, Merelli persuaded him to write Nabucco in 1842 and its opening performance made Verdi famous. Legend has it that it was the words of the famous Va pensiero chorus of the Hebrew slaves that inspired Verdi to write music again.

A large number of operas followed in the decade after 1843, a period which Verdi was to describe as his "galley years". These included his I Lombardi in 1843 and Ernani in 1844.

For some, the most original and important opera that Verdi wrote is Macbeth in 1847. For the first time, Verdi attempted an opera without a love story, breaking a basic convention in 19th Century Italian opera.

In 1847, I Lombardi, revised and renamed Jerusalem, was produced by the Paris Opera and, due to a number of Parisian conventions that had to be honored (including extensive ballets), became Verdi's first work in the French Grand opera style.

Middle years

Sometime in the mid-1840s, after the death of Margherita Barezzi, Verdi began an affair with Giuseppina Strepponi, a soprano in the twilight of her career. Their cohabitation before marriage was regarded as scandalous in some of the places they lived, but Verdi and Giuseppina married on 29 August 1859 at Collonges-sous-Salève, near Geneva. While living in Busseto with Strepponi, Verdi bought an estate two miles from the town in 1848. Initially, his parents lived there, but, after his mother's death in 1851, he made the Villa Verdi at Sant'Agata his home until his death.

As the "galley years" were drawing to a close, Verdi created one of his greatest masterpieces, Rigoletto which premiered in Venice in 1851. Based on a play by Victor Hugo (Le roi s'amuse), the libretto had to undergo substantial revisions in order to satisfy the epoch's censorship, and the composer was on the verge of giving it all up a number of times. The opera quickly became a great success.

With Rigoletto Verdi sets up his original idea of musical drama as a cocktail of heterogeneous elements, embodying social and cultural complexity, and beginning from a distinctive mixture of comedy and tragedy. Rigoletto's musical range includes band-music such as the first scene or the song La donna è mobile, Italian melody such as the famous quartet Bella figlia dell'amore, chamber music such as the duet between Rigoletto and Sparafucile and powerful and concise declamatos often based on key-notes like the C and C# notes in Rigoletto and Monterone's upper register.

There followed the second and third of the three major operas of Verdi's "middle period": in 1853 Il Trovatore was produced in Rome and La traviata in Venice. The latter was based on Alexandre Dumas, fils' play The Lady of the Camellias.

Between 1855 and 1867 an outpouring of great Verdi operas were to follow, among them such repertory staples as Un ballo in maschera (1859), La forza del destino (commissioned by the Imperial Theatre of Saint Petersburg for 1861 but not performed until 1862), and a revised version of Macbeth (1865). Other somewhat less often performed include Les vêpres siciliennes (1855) and Don Carlos (1867), both commissioned by the Paris Opera and initially given in French. Today, these latter two operas are most often performed in their revised Italian versions. Simon Boccanegra followed in 1857.

In 1869, Verdi was asked to compose a section for a Requiem Mass in memory of Gioacchino Rossini and proposed that this Requiem should be a collection of sections composed by other Italian contemporaries of Rossini. The Requiem was compiled and completed, but it was not performed in Verdi's lifetime. Five years later, Verdi reworked his "Libera Me" section of the Rossini Requiem and made it a part of his Requiem Mass, honoring the famous novelist and poet Alessandro Manzoni, who had died in 1873. The complete Requiem was first performed at the cathedral in Milan, on 22 May 1874.

Verdi's grand opera, Aida, is sometimes thought to have been commissioned for the celebration of the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, but, according to one major critic , Verdi turned down the Khedive's invitation to write an "ode" for the new opera house he was planning to inaugurate as part of the canal opening festivities. The opera house actually opened with a production of Rigoletto. It was later in 1869/70, when the organizers again approached Verdi (but this time with the idea of writing an opera), that he again turned them down. When they warned him that they would ask Charles Gounod instead and then threatened to engage Richard Wagner's services, Verdi began to show considerable interest, and agreements were signed in June 1870.

In fact, the two composers, who were the leaders of their respective schools of music, seemed to resent each other greatly. They never met. Verdi's comments on Wagner and his music are few and hardly benevolent ("He invariably chooses, unnecessarily, the untrodden path, attempting to fly where a rational person would walk with better results"), but at least one of them is kind: upon learning of Wagner's death, Verdi lamented: "Sad, sad, sad! ... a name that will leave a most powerful impression on the history of art." Of Wagner's comments on Verdi, only one is well-known. After listening to Verdi's Requiem, the great German, prolific and eloquent in his comments on some other composers, said, "It would be best not to say anything."

Twilight and Death

During the following years Verdi worked on revising some of his earlier scores, most notably new versions of Don Carlos, La forza del destino, and Simon Boccanegra.

Otello, based on William Shakespeare's play, with a libretto written by the younger composer of Mefistofele, Arrigo Boito, premiered in Milan in 1887. Its music is "continuous" and cannot easily be divided into separate "numbers" to be performed in concert. Some feel that although masterfully orchestrated, it lacks the melodic lustre so characteristic of Verdi's earlier, great, operas, while many critics consider it Verdi's greatest tragic opera, containing some of his most beautiful, expressive music and some of his richest characterizations. In addition, it lacks a prelude, something Verdi listeners are not accustomed to. Arturo Toscanini performed as cellist in the Orchestra at the world premiere and began his friendship with Verdi (a composer he revered as highly as Beethoven).

Verdi's last opera, Falstaff, whose libretto was also by Boito, was based on Shakespeare's Merry Wives of Windsor and Victor Hugo's subsequent translation. It was an international success and is one of the supreme comic operas which shows Verdi's genius as a contrapuntist.

In 1894, Verdi composed a short ballet for a French production of Otello, his last purely orchestral composition. Years later, Arturo Toscanini recorded the music for RCA Victor with the NBC Symphony Orchestra which complements the 1947 Toscanini performance of the complete opera.

In 1897, Verdi completed his last composition, a setting of the traditional Latin text Stabat Mater. This was the last of four sacred works that Verdi composed, Quattro Pezzi Sacri, which are often performed together or separately. The first performance of the four works was on April 7, 1898, at the Grande Opéra, Paris. The four works are: Ave Maria for mixed chorus; Stabat Mater for mixed chorus and orchestra; Laudi alla Vergine Maria for female chorus; and Te Deum for double chorus and orchestra.

While staying at the Grand Hotel et de Milan in Milan, Verdi had a stroke on January 21, 1901. He grew gradually more feeble and died six days later, on January 27, 1901. Arturo Toscanini conducted the vast forces of combined orchestras and choirs comprised of musicians from throughout Italy at the State Funeral for Verdi in Milan, following the composer's death. To date, it remains the largest public assembly of any event in the history of Italy.

Verdi's role in the Risorgimento

Music historians have long perpetuated a myth about the famous Va, pensiero chorus sung in the third act of Nabucco. The myth reports that, when the Va, pensiero chorus was sung in Milan, then belonging to the large part of Italy under Austrian domination, the audience, responding with nationalistic fervor to the exiled slaves' lament for their lost homeland, demanded an encore of the piece. As encores were expressly forbidden by the government at the time, such a gesture would have been extremely significant. However, recent scholarship puts this to rest. Although the audience did indeed demand an encore, it was not for Va, pensiero but rather for the hymn Immenso Jehova, sung by the Hebrew slaves to thank God for saving His people. In light of these new revelations, Verdi's position as the musical figurehead of the Risorgimento has been correspondingly downplayed.

On the other hand, during rehearsals, workmen in the theatre stopped what they were doing during "Va, pensiero" and applauded at the conclusion of this haunting melody while the growth of the "indentification of Verdi's music with Italian nationalist politics" is judged to have begun in the summer 1846 in relation to a chorus from Ernani in which the name of one of its characters, "Carlo", was changed to "Pio", a reference to Pope Piux IX's grant to amnesty to political prisons.

The myth of Verdi as Risorgimento's composer also reports that the slogan "Viva VERDI" was used throughout Italy to secretly call for Vittorio Emanuele Re D'Italia (Victor Emmanuel King of Italy), referring to Victor Emmanuel II, then king of Sardinia.

The Chorus of the Hebrews (the English title for Va, pensiero) has another appearance in Verdi folklore. Prior to his body being driven from the cemetery to the official memorial service and its final resting place at the Casa di Riposo, Arturo Toscanini conducted a chorus of 820 singers in "Va, pensiero". At the Casa, the Miserere from Il trovatore was sung.

Style

Verdi's predecessors who influenced his music were Rossini, Bellini, Giacomo Meyerbeer and, most notably, Gaetano Donizetti and Saverio Mercadante. With the possible exception of Otello and Aida, he was free of Wagner's influence. Although respectful of Gounod, Verdi was careful not to learn anything from the Frenchman whom many of Verdi's contemporaries regarded as the greatest living composer. Some strains in Aida suggest at least a superficial familiarity with the works of the Russian composer Mikhail Glinka, whom Franz Liszt, after his tour of the Russian Empire as a pianist, popularized in Western Europe.

Throughout his career, Verdi rarely utilised the high C in his tenor arias, citing the fact that the opportunity to sing that particular note in front of an audience distracts the performer before and after the note appears. However, he did provide high Cs to Duprez in Jérusalem and to Tamberlick in the original version of La forza del destino. The high C often heard in the aria Di quella pira does not appear in Verdi's score.

Although his orchestration is often masterful, Verdi relied heavily on his melodic gift as the ultimate instrument of musical expression. In fact, in many of his passages, and especially in his arias, the harmony is ascetic, with the entire orchestra occasionally sounding as if it were one large accompanying instrument - a giant-sized guitar playing chords. Some critics maintain he paid insufficient attention to the technical aspect of composition, lacking as he did schooling and refinement. Verdi himself once said, "Of all composers, past and present, I am the least learned." He hastened to add, however, "I mean that in all seriousness, and by learning I do not mean knowledge of music."

However, it would be incorrect to assume that Verdi underestimated the expressive power of the orchestra or failed to use it to its full capacity where necessary. Moreover, orchestral and contrapuntal innovation is characteristic of his style: for instance, the strings producing a rapid ascending scale in Monterone's scene in Rigoletto accentuate the drama, and, in the same opera, the chorus humming six closely grouped notes backstage portrays, very effectively, the brief ominous wails of the approaching tempest. Verdi's innovations are so distinctive that other composers do not use them; they remain, to this day, some of Verdi's signatures.

Verdi was one of the first composers who insisted on patiently seeking out plots to suit his particular talents. Working closely with his librettists and well aware that dramatic expression was his forte, he made certain that the initial work upon which the libretto was based was stripped of all "unnecessary" detail and "superfluous" participants, and only characters brimming with passion and scenes rich in drama remained.

Many of his operas, especially the later ones from 1851 onwards are a staple of the standard repertoire. No composer of Italian opera has managed to match Verdi's popularity, perhaps with the exception of Giacomo Puccini.

Verdi's operas

| # | Title | Libretist | Act, Language |

Premiere details | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Oberto | Antonio Piazza | Two acts, Italian |

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, November 17, 1839 |

|

| 2 | Un giorno di regno | Felice Romani | Two acts, Italian |

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, September 5, 1840 |

|

| 3 | Nabucco | Temistocle Solera | Four acts, Italian |

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, March 9, 1842 |

|

| 4 | I Lombardi alla prima crociata | Temistocle Solera | Four acts, Italian |

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, February 11, 1843 |

|

| 5 | Ernani | Francesco Maria Piave | Four acts, Italian |

Teatro La Fenice, Venice, March 9, 1844 |

|

| 6 | I due Foscari | Francesco Maria Piave | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro Argentina, Rome, November 3, 1844 |

|

| 7 | Giovanna d'Arco | Temistocle Solera | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, February 15, 1845 |

|

| 8 | Alzira | Salvatore Cammarano | Two acts, Italian |

Teatro San Carlo, Naples, August 12, 1845 |

|

| 9 | Attila | Temistocle Solera | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro La Fenice, Venice, March 17, 1846 |

|

| 10 | Macbeth | Francesco Maria Piave | Four acts, Italian |

Teatro della Pergola, Florence, March 14, 1847 |

|

| 11 | I masnadieri | Andrea Maffei | Four acts, Italian |

Her Majesty's Theatre, London, July 22, 1847 |

|

| 12 | Jérusalem | Alphonse Royer, Gustave Vaëz |

Four acts, French |

Paris Opéra, Paris, November 26, 1847 |

French version of I Lombardi alla prima crociata |

| 13 | Il corsaro | Francesco Maria Piave | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro Grande, Trieste, 25 October 1848 |

|

| 14 | La battaglia di Legnano | Salvatore Cammarano | Four acts, Italian |

Teatro Argentina, Rome, January 27, 1849 |

|

| 15 | Luisa Miller | Salvatore Cammarano | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro San Carlo, Naples, December 8, 1849 |

|

| 16 | Stiffelio | Francesco Maria Piave | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro Grande, Trieste, November 16, 1850 |

|

| 17 | Rigoletto | Francesco Maria Piave | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro La Fenice, Venice, March 11, 1851 |

|

| 18 | Il trovatore | Leone Emanuele Bardare, Salvatore Cammarano |

Four acts, Italian |

Teatro Apollo, Rome, January 19, 1853 |

|

| 19 | La traviata | Francesco Maria Piave | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro la Fenice, Venice, March 6, 1853 |

|

| 20 | Les vêpres siciliennes | Charles Duveyrier, Eugène Scribe |

Five acts, French |

Paris Opéra, Paris, June 13, 1855 |

|

| 21 | Giovanna de Guzman | Eugenio Caimi | Five acts, Italian |

Teatro Regio, Parma, December 26, 1855 |

Italian version of Les vêpres siciliennes |

| 22 | Le trouvère | Leone Emanuele Bardare, Salvatore Cammarano |

Four acts, Italian |

Paris Opéra, Paris, 1857 |

Revised version of Il trovatore with a ballet added |

| 23 | Simon Boccanegra | Francesco Maria Piave | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro La Fenice, Venice, March 12, 1857 |

|

| 24 | Aroldo | Francesco Maria Piave | Four acts, Italian |

Teatro Nuovo, Rimini, August 16, 1857 |

Revision of Stiffelio |

| 25 | Un ballo in maschera | Antonio Somma | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro Apollo, Rome, February 17, 1859 |

|

| 26 | La forza del destino | Francesco Maria Piave | Four acts, Italian |

Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, Saint Petersburg, November 10, 1862 |

|

| 27 | Macbeth | Francesco Maria Piave | Four acts, Italian |

Théâtre Lyrique, Paris, April 21, 1865 |

Revised version |

| 28 | Don Carlos | Camille du Locle, Joseph Méry |

Five acts, French |

Paris Opéra, Paris, March 11, 1867 |

|

| 29 | La forza del destino | Francesco Maria Piave | Four acts, Italian |

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, February 27, 1869 |

Revised version with text addition by Antonio Ghislanzoni |

| 30 | Aida | Antonio Ghislanzoni | Four acts, Italian |

Khedivial Opera House, Cairo, December 24, 1871 |

|

| 31 | Don Carlo | Camille du Locle, Joseph Méry |

Five acts, Italian |

Teatro San Carlo, Naples, 1872 |

First revision of Don Carlos, translated by Achille de Lauzières, with additions by Antonio Ghislanzoni |

| 32 | Simon Boccanegra | Francesco Maria Piave | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, March 24, 1881 |

Revised version with text changes by Arrigo Boito |

| 33 | La force du destin | Francesco Maria Piave | Four acts, French |

Antwerp, March 14, 1881 |

Revised version of La forza del destino translated by Charles Nuitter and Camille du Locle |

| 34 | Don Carlo | Camille du Locle, Joseph Méry |

Four acts, Italian |

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, January 10, 1884 |

Second revision of Don Carlos with Camille du Locle and Charles Nuitter. Omitted act 1 and the ballet. |

| 35 | Don Carlo | Camille du Locle, Joseph Méry |

Five acts, Italian |

Teatro Municipale, Modena, December 29, 1886 |

Third revision of Don Carlos with Angelo Zanardini (Fontainebleau scene) |

| 36 | Otello | Arrigo Boito | Four acts, Italian |

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, February 5, 1887 |

|

| 37 | Falstaff | Arrigo Boito | Three acts, Italian |

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, February 9, 1893 |

Eponyms

- The Verdi Inlet on the Beethoven Peninsula of Alexander Island just off Antarctica

- Verdi Square at Broadway and West 72nd Street in Manhattan

- Asteroid 3975 Verdi

Trivia

Verdi's name literally translates as "Joseph Green" in English. Musical comedian Victor Borge often referred to the famous composer as "Joe Green" in his act, saying that "Giuseppe Verdi" was merely his "stage name".

The same joke-translation is mentioned in Evil Under the Sun (1982 film) by Patrick Redfern (played by Nicholas Clay) to Hercule Poirot ( Peter Ustinov), a prank which inadvertedly gives Poirot the answer to the murder.

The famous portrait of Verdi by Giovanni Boldini was the main inspiration of Luchino Visconti in creating the character of Burt Lancaster in his film Il Gattopardo.