Longship

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Air & Sea transport; British History 1500 and before (including Roman Britain)

Longships were ships primarily used by the Scandinavian Vikings and the Saxons to raid coastal and inland settlements during the European Middle Ages. They are often called " longboats", but "longship" is more accurate. The vessels were also used for long distance trade and commerce, and for exploratory voyages to Iceland, Greenland, and beyond. Longship design evolved over several centuries and was fully developed by about the 9th century. In Norway traditional longships were used until the 13th century, and the character and appearance of these ships were reflected in western Norwegian boat-building traditions until the early 20th century.

The longship was characterized as a graceful, long, narrow, light wooden boat with a shallow draft designed for speed. The ship's shallow draft allowed navigation in waters only one metre deep and permitted rapid beach landings, while its light weight enabled it to be carried over portages. Longships were also symmetrical, allowing the ship to reverse direction quickly. Longships were fitted with oars along almost the entire length of the boat itself. Later versions sported a rectangular sail on a single mast which was used to augment the effort of the rowers, particularly during long journeys.

Longships were the epitome of Scandinavian naval power at the time, and were highly valued possessions. They were often owned by coastal farmers and commissioned by the king in times of conflict, in order to build a powerful naval force. While longships were used by the Vikings in warfare, they were troop transports, not warships. In the tenth century, these boats would sometimes be tied together in battle to form a steady platform for infantry warfare.They were called dragonships by enemies such as the English.

Development history

The famous Viking longships did not suddenly spring into being, but developed over hundreds of years. Archaeologists have uncovered a number of ships and boats showing this development, and rock carvings and runestones which predate the longships also indicate a long shipbuilding tradition in Scandinavia.

Early ships

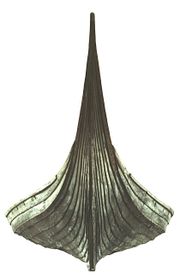

The Hjortspring ship

One of the early precursors of the longship was the Hjortspring boat. This 13 m (40 feet) boat was found on the Hjortspring farm on the Danish island of Als. It was probably built between 200 B.C and 350 B.C., of five limewood planks. The boat has been interpreted as an early war canoe that was lowered into a pool as a sacrifice. Its design already shows some of the features of later longships, such as clinker construction. The boards for the hull were cut into wedge-shaped pieces or "cleats", and hazelwood ribs were fastened inside. The method of attaching the boards and gunwales was later adapted to longships to make them flexible for ocean voyages. The boat was propelled by paddles.

The Nydam ship

The Nydam ship (or Nydam Oak Boat) had a much improved design compared to the Hjortspring boat. It was one of three ships found in a series of excavations in the middle of the 19th century 8km from Sønderborg near Schleswig on the German-Danish border. The ship was dated to about 315 A.D using dendochronology. The Nydam ship was both larger and much more technologically advanced than the Hjortspring boat. The ship measured 23 m (75 feet) in length and was built from oak. It was originally believed that its planks (technically " strakes") were of a single piece running the full length of the hull. However, while sampling the wood for dating, it was discovered that they were composed of a few long pieces carefully connected by invisible joints. The planks were held together by iron rivets and formed a curved prow and stern. The Nydam ship is the first known ship in Northern Europe to use oars rather than paddles for propulsion. The oars were held in place by bent branches secured to the rail. This allowed greater speed and easier rowing for the crew. The ship had a narrow, V-shaped hull giving it superior speed and agility. However, this also made it to rather unstable, and unable to support mast and sail.

The Kvalsund ship

Two ships dated to the 7th century were found in Kvalsund, Norway. Both were of similar design. Despite the shorter length of about 18m (61 feet), the larger Kvalsund ship was far wider than the older vessels mentioned above, with a width of about 3.5 m (10 feet). It had a clearly defined, strong keel. These key improvements allowed it to maintain a course even under adverse weather conditions. The Kvalsund ship had oars that were fastened to the rails with wooden pegs or trenails. No sailing rig has been found, although the ship certainly could have carried mast and sail. Apart from the lack of rigging, the Kvalsund ship already had most of the characteristics of a true longship.

The Oseberg ship

The continuing evolution of the Scandinavian sailing ships is evident in the Oseberg ship, which has been dated to c. 815–820 A.D. and was found in a burial mound in Vestfold south of Oslo, Norway. The Oseberg can be considered one of the first true longships. It features a built-in mast and mast partner. Compared to later ships, the Oseberg is a rather frail vessel, and it is thought that it was only used in coastal waters, or built especially for the funeral.

By this period the distance between the ship’s ribs was a standard length and the ribs were stronger. The hulls had more of a V shape and the length expanded from gunwale to gunwale. These new hulls had poor lateral stability but made up for it in speed. It had wood fastened together instead of single pieces which allowed greater stability and agility.

The Oseberg has a length of 21.5 meters, a width of 5 meters and a total weight of 11 tons.

The Vikings were excellent sailors their boats were called longships. Longships were light, sleek, stable, strong and easy to manoeuvre. Being long and thin they made great warships. The hull cut through the water fast. The boat was also flexible, so it moved with the action of the waves. The longship has a flat bottom with a shallow draught which allowed the Viking to sail into shallow waters bays and even the shore line. Longships are around 28 – 30 meters long in size and built to hold more than 100 men. The boats speed can get up to 30 – 35 kilometres per hour because the Vikings had both oars and sails so they could keep going in any weather condition.

They were constructed out of raw timber. The kneel (the bottom of the boat) was made out of a single trunk, planks were made from split timber, sternposts are cut from large curved logs, angled sections were cut from strong branches and curved sections were cut from curved branches.

In building a longship you would use up to 10 or more tools.

Types of longship

Longships can be classified into a number of different types, depending on size, construction details, and prestige.

Snekke (snekkja)

The snekke was the smallest vessel that would still be considered a longship. A typical snekke might have a length of 17 m, a width of 2.5 m, and a draught of only 0.5 m. It would carry a crew of about 25 men.

Snekkes were one of the most common types of ship. According to historical lore, Canute the Great used 1400 in Norway in 1028, and William the Conqueror used about 600 for the invasion of Britain in 1066.

The Norwegian snekkes, designed for deep fjords and Atlantic weather, typically had more draft than the Danish model designed for low coasts and beaches. Snekkes were so light that they had no need of ports – they could simply be beached, and potentially even carried across a portage.

The snekke continued to evolve after the end of the Viking age, with later Norwegian examples becoming larger and heavier than Viking age ships.

Dragon ships

Dragon ships are known from historical sources, such as the 13th century Göngu-Hrólfs Saga (the Saga of Rollo). Here, the ships are described as elegant and ornately decorated, and used by those who went í Viking (raiding and plundering). According to the historical sources the ships' prows carried carvings of menacing beasts, such as dragons and snakes, allegedly to protect the ship and crew, and to ward off the terrible sea monsters of Norse mythology. It is however likely that the carvings, like those on the Oseberg ship, might have had a ritual purpose, or that the purported effect was to frighten enemies and townspeople. No true dragon ship, as defined by the sagas, has been found by archaeological excavation. Therefore, their existence is only supported by the historical sources.

Roskilde ships

The largest longships so far found, were discovered by Danish archaeologists in Roskilde during development in the harbour-area in 1962 and 1996/7. The ship discovered in 1962, Skuldelev 2 is an oak-built vessel possibly of the skeid type. It was built in the Dublin area around 1042. Skuldelev 2 could carry a crew of some 70-80 and measures just under 100 feet (30 m) in length. In 1996/7 archaeologists discovered the remains of another ship in the harbour. This ship, called the Roskilde 6, has not yet been fully investigated and full details are not available. It is however thought to be around 36m long, and has been dated to the mid-11th century.

The discovery of these ships overturned the skepticism of some historians that longships of this size had ever been constructed. The Roskilde longships may have been a specialized type of cargo ship that the Vikings used for trade.

Construction

After several centuries of evolution, the fully developed longship emerged some time in the middle of the ninth century. Its long, graceful, menacing head figure carved in the stern echoed the designs of its predecessors. The mast was now squared and located toward the middle of the ship, and could be lowered and raised. The hull’s sides were fastened together to allow it to flex with the waves, ensuring stability and integrity. The ships were large enough to carry cargo and passengers on long ocean voyages but still maintained speed and agility, making the longship a versatile warship and cargo carrier.

Selection of wood

Wood was the fundamental material of the longship: it was used in every part of the ship, from the planks for the hull to the mast and oars. The Vikings had developed the selection and cutting of wood to a fine science. They made planks by splitting huge oak trees. The trunks were cut radially from tall trees, which contained few knots. The planks had exceptional strength, due to the fact that they were cut following the grain of the wood. The planks also were cut in such a way that they did not shrink or warp as they dried. Shipbuilders used fresh-cut trees rather than seasoned timber because it was easier to work. Curved pieces were made from trees that had grown naturally in that shape. This allowed the part to be made from a single piece of wood, cutting down the weight of the ship. About 100 oak trees were used to build a longship.

Keel, stems and hull

The Viking shipbuilders had no written diagrams or standard written design plan. The shipbuilder pictured the longship before its construction, and the ship was then built from the ground up. The keel and stems were made first. The shape of the stem was based on segments of circles of varying sizes. The next step was building the strakes – the lines of planks joined endwise from stern to stern. Nearly all longships were clinker built, meaning that each hull plank overlapped the next.

As the strakes reached the desired height, the interior frame and cross beams were added. The parts were held together with iron rivets, as well as spruce strips that were fastened to the ribs inside of the keel. Longships had about five rivets for each yard of plank.

The longships’ wider hulls provided strength beneath the waterline which gave more stability, making the longship less likely to tip or bring in water. The hull was waterproofed with moss drenched in tar. In the autumn the ships would be tarred and then left in a boathouse over the winter to allow time for the tar to dry. To keep the sea out, wooden disks were put into the oar holes. These could be shut from the inside when the oars were not in use.

Sail and mast

Even though no longship sail has been found, accounts verify that longships had square sails. Sails measured perhaps 35 to 40 feet across, and were made of wadmill (rough wool) which was woven by looms. Unlike the knarrs, the longship sail was not stitched.

The sail was held in place by the mast. The mast was supported by a large block of wood called "kerling" ("Old Woman" in Old Norse). (Trent) The kerling was made of oak, and was as tall as a Viking man. The kerling lay across the two ribs and ran width-wise along the keel. The kerling also had a companion: the "mast fish", a wooden piece above the kerling that provided extra help in keeping the mast erect. (information need for how long boat construction and sail creation needed.)

Navigation and propulsion

Navigation

The Vikings were experts in judging speed and wind direction, and in knowing the current and when to expect high and low tides. Viking navigational techniques are not well understood, but historians postulate that the Vikings probably had some sort of primitive astrolabe and used the stars to plot their course.

A Viking named Stjerner Oddi compiled a chart showing the direction of dawn and twilight, which enabled navigators to sail longships from place to place with ease. Almgren, an earlier Viking, told of another method: "All the measurements of angles were made with what was called a 'half wheel' (a kind of half sun-diameter which corresponds to about sixteen seconds of arc). This was something that was known to every skipper at that time, or to the long-voyage pilot or 'kendtmand' ('man who knows the way') who sometimes went along on voyages... When the sun was in the sky, it was not, therefore, difficult to find the four points of the compass, and determining latitude did not cause any problems either." (Algrem)

Birds provided a helpful guide to finding land. A Viking legend states that Vikings used to take caged crows aboard ships and let them loose if they got lost. The crows would instinctively find land, giving the Viking navigators their direction. Little is known of Viking compasses, though Viking legends do tell of small magnetic stones floating on a piece of wood in water to provide a point of navigational reference.

Propulsion

The longship had two methods of propulsion: oars and sail. At sea, the sail enabled longships to travel faster than by oar and to cover long distances. Sails could be raised or lowered quickly. Oars were used when land was spotted, to gain speed quickly (when there was no wind), and to get the boat started. In combat, the variability of wind power made rowing the chief means of propulsion.

Longships were not fitted with benches. When rowing, the crew sat on sea chests (chests containing their personal possessions) that would otherwise take up space. The chests were made the same size and were the perfect height for a Viking to sit on and row. Longships had hooks for oars to fit into, but smaller oars were also used, with crooks or bends to be used as oarlocks. If there were no holes then a loop of rope kept the oars in place.

Legacy

The Vikings were major contributors to the shipbuilding technology of their day. Their shipbuilding methods spread through extensive contact with other cultures, and ships from the 11th and 12th centuries are known to borrow many of the longships’ design features, despite the passing of many centuries. The 'Lancha Poveira', a boat from Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal, originates from the longship, but without a long stern and bow, and with a Mediterranean sail. It was used until the 1950s. Today there is just one boat: Fé em Deus.

Many historians, archaeologists and adventurers have reconstructed longships in an attempt to understand how they worked. These re-creators have been able to identify many of the advances that the Vikings implemented in order to make the longship a superior vessel. One replica longship covered 223 nautical miles in a single day, and another re-creator was able to go faster than 8 knots in his longship.

The longship was a master of all trades: it was wide and stable, yet light, fast and nimble. With all these qualities combined in one ship, the longship was unrivaled for centuries, until the arrival of the great gunboats and galleons.

Famous longships

- The Oseberg ship and the Gokstad ship of Oslo.

- The Ormen Lange ("The Long Serpent") was the most famous longship of Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason.

- The Mora was the ship given to William the Conqueror by his wife, Matilda, and used as the flagship in the conquest of England.

- The Sea Stallion, the largest Viking ship replica ever made, is a new 30 meter replica of the skuldelev 2, and is going to be sailed from Roskilde, Denmark to Dublin in 2007 to commemorate the voyage of the original.