Schizophrenia

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Health and medicine

| Schizophrenia Classification and external resources |

||

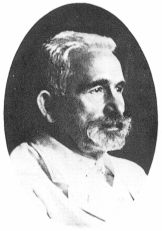

| Eugen Bleuler (1857–1939) coined the term "Schizophrenia" in 1908 | ||

| ICD- 10 | F 20. | |

| ICD- 9 | 295 | |

| OMIM | 181500 | |

| DiseasesDB | 11890 | |

| MedlinePlus | 000928 | |

| eMedicine | med/2072 emerg/520 | |

| MeSH | F03.700.750 | |

Schizophrenia (pronounced /ˌskɪtsəˈfriːniə/), from the Greek roots schizein (σχίζειν, "to split") and phrēn, phren- (φρήν, φρεν-, "mind") is a psychiatric diagnosis that describes a mental disorder characterized by abnormalities in the perception or expression of reality. It most commonly manifests as auditory hallucinations, paranoid or bizarre delusions or disorganized speech and thinking in the context of significant social or occupational dysfunction. Onset of symptoms typically occurs in young adulthood, with approximately 0.4–0.6% of the population affected. Diagnosis is based on the patient's self-reported experiences and observed behaviour. No laboratory test for schizophrenia currently exists.

Studies suggest that genetics, early environment, neurobiology and psychological and social processes are important contributory factors. Current psychiatric research is focused on the role of neurobiology, but no single organic cause has been found. Due to the many possible combinations of symptoms, there is debate about whether the diagnosis represents a single disorder or a number of discrete syndromes. For this reason, Eugen Bleuler termed the disease the schizophrenias (plural) when he coined the name. Despite its etymology, schizophrenia is not synonymous with dissociative identity disorder, previously known as multiple personality disorder or split personality; in popular culture the two are often confused.

Increased dopaminergic activity in the mesolimbic pathway of the brain is consistently found in schizophrenic individuals. The mainstay of treatment is pharmacotherapy with antipsychotic medications; these primarily work by suppressing dopamine activity. Dosages of antipsychotics are generally lower than in the early decades of their use. Psychotherapy, vocational and social rehabilitation are also important. In more serious cases—where there is risk to self and others—involuntary hospitalization may be necessary, though hospital stays are less frequent and for shorter periods than they were in previous years.

The disorder is primarily thought to affect cognition, but it also usually contributes to chronic problems with behaviour and emotion. People diagnosed with schizophrenia are likely to be diagnosed with comorbid conditions, including clinical depression and anxiety disorders; the lifetime prevalence of substance abuse is typically around 40%. Social problems, such as long-term unemployment, poverty and homelessness, are common and life expectancy is decreased; the average life expectancy of people with the disorder is 10 to 12 years less than those without, owing to increased physical health problems and a high suicide rate.

Signs and symptoms

A person diagnosed with schizophrenia may demonstrate disorganized and unusual thinking and speech, auditory hallucinations, and delusions. Social isolation commonly occurs for a variety of reasons. Impairment in social cognition is associated with schizophrenia, as are symptoms of paranoia from delusions and hallucinations, and the negative symptoms of apathy and avolition. In one uncommon subtype, the person may be largely mute, remain motionless in bizarre postures, or exhibit purposeless agitation; these are signs of catatonia. No one sign is diagnostic of schizophrenia, and all can occur in other medical and psychiatric conditions. The current classification of psychoses holds that symptoms need to have been present for at least one month in a period of at least six months of disturbed functioning. A schizophrenia-like psychosis of shorter duration is termed a schizophreniform disorder.

Late adolescence and early adulthood are peak years for the onset of schizophrenia. These are critical periods in a young adult's social and vocational development, and they can be severely disrupted. To minimize the effect of schizophrenia, much work has recently been done to identify and treat the prodromal (pre-onset) phase of the illness, which has been detected up to 30 months before the onset of symptoms, but may be present longer. Those who go on to develop schizophrenia may experience the non-specific symptoms of social withdrawal, irritability and dysphoria in the prodromal period, and transient or self-limiting psychotic symptoms in the prodromal phase before psychosis becomes apparent.

Schneiderian classification

The psychiatrist Kurt Schneider (1887–1967) listed the forms of psychotic symptoms that he thought distinguished schizophrenia from other psychotic disorders. These are called first-rank symptoms or Schneider's first-rank symptoms, and they include delusions of being controlled by an external force; the belief that thoughts are being inserted into or withdrawn from one's conscious mind; the belief that one's thoughts are being broadcast to other people; and hearing hallucinatory voices that comment on one's thoughts or actions or that have a conversation with other hallucinated voices. The reliability of first-rank symptoms has been questioned, although they have contributed to the current diagnostic criteria.

Positive and negative symptoms

Schizophrenia is often described in terms of positive (or productive) and negative (or deficit) symptoms. Positive symptoms include delusions, auditory hallucinations, and thought disorder, and are typically regarded as manifestations of psychosis. Negative symptoms are so-named because they are considered to be the loss or absence of normal traits or abilities, and include features such as flat or blunted affect and emotion, poverty of speech ( alogia), inability to experience pleasure ( anhedonia), and lack of motivation ( avolition). Despite the appearance of blunted affect, recent studies indicate that there is often a normal or even heightened level of emotionality in schizophrenia, especially in response to stressful or negative events. A third symptom grouping, the disorganization syndrome, is commonly described, and includes chaotic speech, thought, and behaviour. There is evidence for a number of other symptom classifications.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the self-reported experiences of the person, and possibly abnormalities in behaviour reported by family members, friends or co-workers, followed by a clinical assessment by a psychiatrist, social worker, clinical psychologist or other mental health professional. Psychiatric assessment typically involves some form of mental status examination and taking a psychiatric history. There are standardized criteria for the diagnosis, depending on the presence, severity and duration of certain signs and symptoms. There are several psychiatric illnesses other than schizophrenia that may present with psychotic symptoms. These include bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, schizoaffective disorder, drug intoxication, brief drug-induced psychosis, and schizophreniform disorder.

Assessment sometimes includes general medical and neurological examinations to exclude medical illnesses which may rarely present with psychotic schizophrenia-like symptoms, such as metabolic disturbance, systemic infection, syphilis, HIV infection, epilepsy, and brain lesions. It may be necessary to rule out a delirium, which can be distinguished by visual hallucinations, acute onset and fluctuating level of consciousness, and indicates an underlying medical illness. Investigations are not generally repeated for relapse unless there is a specific medical indication or possible adverse effects from antipsychotic medication.

The most widely used criteria for diagnosing schizophrenia are from the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the current version being DSM-IV-TR, and the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, currently the ICD-10. The latter criteria are typically used in European countries while the DSM criteria are used in the USA or the rest of the world, as well as prevailing in research studies. The ICD-10 criteria put more emphasis on Schneiderian first rank symptoms although, in practice, agreement between the two systems is high. The WHO has developed the tool SCAN (Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry) which can be used for diagnosing a number of psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia.

DSM IV-TR Criteria

To be diagnosed with schizophrenia, a person must display:

- Characteristic symptoms: Two or more of the following, each present for much of the time during a one-month period (or less, if symptoms remitted with treatment)

- delusions

- hallucinations

- disorganized speech (e.g., frequent derailment or incoherence; speaking in abstracts). See thought disorder.

- grossly disorganized behaviour (e.g. dressing inappropriately, crying frequently) or catatonic behaviour

- negative symptoms, i.e., affective flattening (lack or decline in emotional response), alogia (lack or decline in speech), or avolition (lack or decline in motivation).

- Note: If delusions are judged to be bizarre, or hallucinations consist of hearing one voice participating in a running commentary of the patient's actions or of hearing two or more voices conversing with each other, only that symptom is required above. The speech disorganization criterion is only met if it is severe enough to substantially impair communication.

- Social/occupational dysfunction: For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, one or more major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care, are markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset.

- Duration: Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least six months. This six-month period must include at least one month of symptoms (or less, if symptoms remitted with treatment).

Schizophrenia cannot be diagnosed if symptoms of mood disorder or pervasive developmental disorder are present, or the symptoms are the direct result of a general medical condition or a substance, such as abuse of a drug or medication.

Subtypes

Historically, schizophrenia in the West was classified into simple, catatonic, hebephrenic (now known as disorganized), and paranoid. The DSM contains five sub-classifications of schizophrenia:

- paranoid type: where delusions and hallucinations are present but thought disorder, disorganized behaviour, and affective flattening are absent (DSM code 295.3/ICD code F20.0)

- disorganized type: named 'hebephrenic schizophrenia' in the ICD. Where thought disorder and flat affect are present together (DSM code 295.1/ICD code F20.1)

- catatonic type: prominent psychomotor disturbances are evident. Symptoms can include catatonic stupor and waxy flexibility (DSM code 295.2/ICD code F20.2)

- undifferentiated type: psychotic symptoms are present but the criteria for paranoid, disorganized, or catatonic types have not been met (DSM code 295.9/ICD code F20.3)

- residual type: where positive symptoms are present at a low intensity only (DSM code 295.6/ICD code F20.5)

The ICD-10 recognises a further two subtypes:

- post-schizophrenic depression: a depressive episode arising in the aftermath of a schizophrenic illness where some low-level schizophrenic symptoms may still be present (ICD code F20.4)

- simple schizophrenia: insidious but progressive development of prominent negative symptoms with no history of psychotic episodes (ICD code F20.6)

Diagnostic issues and controversies

Schizophrenia as a diagnostic entity has been criticised as lacking in scientific validity or reliability, part of a larger criticism of the validity of psychiatric diagnoses in general. One alternative suggests that the issues with the diagnosis would be better addressed as individual dimensions along which everyone varies, such that there is a spectrum or continuum rather than a cut-off between normal and ill. This approach appears consistent with research on schizotypy and of a relatively high prevalence of psychotic experiences and often non-distressing delusional beliefs amongst the general public.

Another criticism is that the definitions used for criteria lack consistency; this is particularly relevant to the evaluation of delusions and thought disorder. More recently, it has been argued that psychotic symptoms are not a good basis for making a diagnosis of schizophrenia as "psychosis is the 'fever' of mental illness—a serious but nonspecific indicator".

Perhaps because of these factors, studies examining the diagnosis of schizophrenia have typically shown relatively low or inconsistent levels of diagnostic reliability. Most famously, David Rosenhan's 1972 study, published as On being sane in insane places, demonstrated that the diagnosis of schizophrenia was (at least at the time) often subjective and unreliable. More recent studies have found agreement between any two psychiatrists when diagnosing schizophrenia tends to reach about 65% at best. This, and the results of earlier studies of diagnostic reliability (which typically reported even lower levels of agreement) have led some critics to argue that the diagnosis of schizophrenia should be abandoned.

In 2004 in Japan, the Japanese term for schizophrenia was changed from Seishin-Bunretsu-Byo (mind-split-disease) to Tōgō-shitchō-shō ( integration disorder). In 2006, campaigners in the UK, under the banner of Campaign for Abolition of the Schizophrenia Label, argued for a similar rejection of the diagnosis of schizophrenia and a different approach to the treatment and understanding of the symptoms currently associated with it.

Alternatively, other proponents have put forward using the presence of specific neurocognitive deficits to make a diagnosis. These take the form of a reduction or impairment in basic psychological functions such as memory, attention, executive function and problem solving. It is these sorts of difficulties, rather than the psychotic symptoms (which can in many cases be controlled by antipsychotic medication), which seem to be the cause of most disability in schizophrenia. However, this argument is relatively new and it is unlikely that the method of diagnosing schizophrenia will change radically in the near future.

The diagnosis of schizophrenia has been used for political rather than therapeutic purposes; in the Soviet Union an additional sub-classification of sluggishly progressing schizophrenia was created. Particularly in the RSFSR (Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic), this diagnosis was used for the purpose of silencing political dissidents or forcing them to recant their ideas by the use of forcible confinement and treatment. In 2000 there were similar concerns regarding detention and 'treatment' of practitioners of the Falun Gong movement by the Chinese government. This led the American Psychiatric Association's Committee on the Abuse of Psychiatry and Psychiatrists to pass a resolution to urge the World Psychiatric Association to investigate the situation in China.

Epidemiology

Schizophrenia occurs equally in males and females although typically appears earlier in men with the peak ages of onset being 20–28 years for males and 26–32 years for females. Much rarer are instances of childhood-onset and late- (middle age) or very-late-onset (old age) schizophrenia. The lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia, that is, the proportion of individuals expected to experience the disease at any time in their lives, is commonly given at 1%. A 2002 systematic review of many studies, however, found a lifetime prevalence of 0.55%. Despite the received wisdom that schizophrenia occurs at similar rates throughout the world, its prevalence varies across the world, within countries, and at the local and neighbourhood level. One particularly stable and replicable finding has been the association between living in an urban environment and schizophrenia diagnosis, even after factors such as drug use, ethnic group and size of social group have been controlled for. Schizophrenia is known to be a major cause of disability. In a 1999 study of 14 countries, active psychosis was ranked the third-most-disabling condition, after quadriplegia and dementia and before paraplegia and blindness.

Causes

While the reliability of the diagnosis introduces difficulties in measuring the relative effect of genes and environment (for example, symptoms overlap to some extent with severe bipolar disorder or major depression), evidence suggests that genetic and environmental factors can act in combination to result in schizophrenia. Evidence suggests that the diagnosis of schizophrenia has a significant heritable component but that onset is significantly influenced by environmental factors or stressors. The idea of an inherent vulnerability (or diathesis) in some people, which can be unmasked by biological, psychological or environmental stressors, is known as the stress-diathesis model. The idea that biological, psychological and social factors are all important is known as the "biopsychosocial" model.

Genetic

Estimates of the heritability of schizophrenia tend to vary owing to the difficulty of separating the effects of genetics and the environment although twin studies have suggested a high level of heritability. It is likely that schizophrenia is a condition of complex inheritance, with several genes possibly interacting to generate risk for schizophrenia or the separate components that can co-occur leading to a diagnosis. Genetic studies have suggested that genes that raise the risk for developing schizophrenia are non-specific, and may also raise the risk of developing other psychotic disorders such as bipolar disorder. Recent research has suggested that rare deletions or duplications of tiny DNA sequences within genes (known as copy number variants) are also linked to increased risk for schizophrenia.

Prenatal

It is thought that causal factors can initially come together in early neurodevelopment, including during pregnancy, to increase the risk of later developing schizophrenia. One curious finding is that people diagnosed with schizophrenia are more likely to have been born in winter or spring, (at least in the northern hemisphere). There is now evidence that prenatal exposure to infections increases the risk for developing schizophrenia later in life, providing additional evidence for a link between in utero developmental pathology and risk of developing the condition.

Social

Living in an urban environment has been consistently found to be a risk factor for schizophrenia. Social disadvantage has been found to be a risk factor, including poverty and migration related to social adversity, racial discrimination, family dysfunction, unemployment or poor housing conditions. Childhood experiences of abuse or trauma have also been implicated as risk factors for a diagnosis of schizophrenia later in life. Parenting is not held responsible for schizophrenia but unsupportive dysfunctional relationships may contribute to an increased risk.

Substance use

The relationship between schizophrenia and drug use is complex, meaning that a clear causal connection between drug use and schizophrenia has been difficult to distinguish. There is strong evidence that using certain drugs can trigger either the onset or relapse of schizophrenia in some people. It may also be the case, however, that people with schizophrenia use drugs to overcome negative feelings associated with both the commonly prescribed antipsychotic medication and the condition itself, where negative emotion, paranoia and anhedonia are all considered to be core features. Amphetamines trigger the release of dopamine and excessive dopamine function is believed to be at least partly responsible for the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia (a theory known as the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia). This is, in part, supported by the fact that amphetamines reliably worsen the symptoms of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia can be triggered by heavy use of hallucinogenic or stimulant drugs. One study suggests that cannabis use can contribute to psychosis, though the researchers suspected cannabis use was only a small component in a broad range of factors.

Psychological

A number of psychological mechanisms have been implicated in the development and maintenance of schizophrenia. Cognitive biases that have been identified in those with a diagnosis or those at risk, especially when under stress or in confusing situations, include excessive attention to potential threats, jumping to conclusions, making external attributions, impaired reasoning about social situations and mental states, difficulty distinguishing inner speech from speech from an external source, and difficulties with early visual processing and maintaining concentration. Some cognitive features may reflect global neurocognitive deficits in memory, attention, problem-solving, executive function or social cognition, while others may be related to particular issues and experiences. Despite a common appearance of "blunted affect", recent findings indicate that many individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia are highly emotionally responsive, particularly to stressful or negative stimuli, and that such sensitivity may cause vulnerability to symptoms or to the disorder. Some evidence suggests that the content of delusional beliefs and psychotic experiences can reflect emotional causes of the disorder, and that how a person interprets such experiences can influence symptomatology. The use of " safety behaviors" to avoid imagined threats may contribute to the chronicity of delusions. Further evidence for the role of psychological mechanisms comes from the effects of therapies on symptoms of schizophrenia.

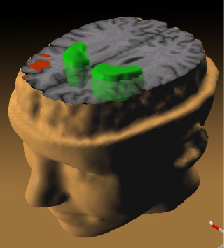

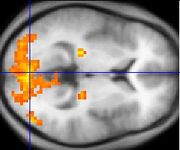

Neural

Studies using neuropsychological tests and brain imaging technologies such as fMRI and PET to examine functional differences in brain activity have shown that differences seem to most commonly occur in the frontal lobes, hippocampus, and temporal lobes. These differences have been linked to the neurocognitive deficits often associated with schizophrenia. The role of antipsychotic medication, which nearly all those studied had taken, in causing such abnormalities is unclear.

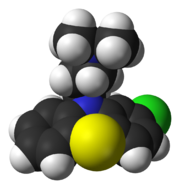

Particular focus has been placed upon the function of dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway of the brain. This focus largely resulted from the accidental finding that a drug group which blocks dopamine function, known as the phenothiazines, could reduce psychotic symptoms. An influential theory, known as the Dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, proposed that a malfunction involving dopamine pathways was the cause of (the positive symptoms of) schizophrenia. This theory is now thought to be overly simplistic as a complete explanation, partly because newer antipsychotic medication (called atypical antipsychotic medication) can be equally effective as older medication (called typical antipsychotic medication), but also affects serotonin function and may have slightly less of a dopamine blocking effect.

Interest has also focused on the neurotransmitter glutamate and the reduced function of the NMDA glutamate receptor in schizophrenia. This has largely been suggested by abnormally low levels of glutamate receptors found in postmortem brains of people previously diagnosed with schizophrenia and the discovery that the glutamate blocking drugs such as phencyclidine and ketamine can mimic the symptoms and cognitive problems associated with the condition. The fact that reduced glutamate function is linked to poor performance on tests requiring frontal lobe and hippocampal function and that glutamate can affect dopamine function, all of which have been implicated in schizophrenia, have suggested an important mediating (and possibly causal) role of glutamate pathways in schizophrenia. Further support of this theory has come from preliminary trials suggesting the efficacy of coagonists at the NMDA receptor complex in reducing some of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia.

There have also been findings of differences in the size and structure of certain brain areas in schizophrenia, starting with the discovery of ventricular enlargement in those for whom negative symptoms were most prominent. However, this has not proven particularly reliable on the level of the individual person, with considerable variation between patients. More recent studies have shown various differences in brain structure between people with and without diagnoses of schizophrenia. While brain structure changes have been found in people diagnosed with schizophrenia who have never been treated with antipsychotic drugs there is evidence that the medication itself might cause additional changes in the brain's structure. However, as with earlier studies, many of these differences are only reliably detected when comparing groups of people, and are unlikely to predict any differences in brain structure of an individual person with schizophrenia.

Treatment and services

The concept of a cure as such remains controversial, as there is no consensus on the definition, although some criteria for the remission of symptoms have recently been suggested. The effectiveness of schizophrenia treatment is often assessed using standardized methods, one of the most common being the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Management of symptoms and improving function is thought to be more achievable than a cure. Treatment was revolutionized in the mid 1950s with the development and introduction of chlorpromazine. A recovery model is increasingly adopted, emphasizing hope, empowerment and social inclusion.

Hospitalization may occur with severe episodes of schizophrenia. This can be voluntary or (if mental health legislation allows it) involuntary (called civil or involuntary commitment). Long-term inpatient stays are now less common due to deinstitutionalization, although can still occur. Following (or in lieu of) a hospital admission, support services available can include drop-in centers, visits from members of a community mental health team or Assertive Community Treatment team, supported employment and patient-led support groups.

In many non-Western societies, schizophrenia may only be treated with more informal, community-led methods. The outcome for people diagnosed with schizophrenia in non-Western countries may actually be better than for people in the West. The reasons for this effect are not clear, although cross-cultural studies are being conducted.

Medication

The mainstay of psychiatric treatment for schizophrenia is an antipsychotic (aka " neuroleptic") medication. These can reduce the "positive" symptoms of psychosis. Most antipsychotics take around 7–14 days to have their main effect.

Though expensive, the newer atypical antipsychotic drugs are usually preferred for initial treatment over the older typical antipsychotics; they are often better tolerated and associated with lower rates of tardive dyskinesia, although they are more likely to induce weight gain and obesity-related diseases. Prolactin elevations have been reported in women with schizophrenia taking atypical antipsychotics. It remains unclear whether the newer antipsychotics reduce the chances of developing neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a rare but serious and potentially fatal neurological disorder most often caused by an adverse reaction to neuroleptic or antipsychotic drugs.

The two classes of antipsychotics are generally thought equally effective for the treatment of the positive symptoms. Some researchers have suggested that the atypicals offer additional benefit for the negative symptoms and cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia, although the clinical significance of these effects has yet to be established. Recent reviews have refuted the claim that atypical antipsychotics have fewer extrapyramidal side effects than typical antipsychotics, especially when the latter are used in low doses or when low potency antipsychotics are chosen.

Response of symptoms to medication is variable; "Treatment-resistant schizophrenia" is a term used for the failure of symptoms to respond satisfactorily to at least two different antipsychotics. Patients in this category may be prescribed clozapine, a medication of superior effectiveness but several potentially lethal side effects including agranulocytosis and myocarditis. Clozapine may have the additional benefit of reducing propensity for substance abuse in schizophrenic patients. For other patients who are unwilling or unable to take medication regularly, long-acting depot preparations of antipsychotics may be given every two weeks to achieve control. The United States of America and Australia are two countries with laws allowing the forced administration of this type of medication on those who refuse but are otherwise stable and living in the community. Some findings have found that in the longer-term some individuals may do better not taking antipsychotics. Despite the promising results of early pilot trials, omega-3 fatty acids failed to improve schizophrenic symptoms, according to the most recent meta-analysis.

Psychological and social interventions

Psychotherapy is also widely recommended and used in the treatment of schizophrenia, although services may often be confined to pharmacotherapy because of reimbursement problems or lack of training.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is used to reduce symptoms and improve related issues such as self-esteem, social functioning, and insight. Although the results of early trials were inconclusive, more recent reviews suggest that CBT can be an effective treatment for the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. Another approach is cognitive remediation therapy, a technique aimed at remediating the neurocognitive deficits sometimes present in schizophrenia. Based on techniques of neuropsychological rehabilitation, early evidence has shown it to be cognitively effective, with some improvements related to measurable changes in brain activation as measured by fMRI. A similar approach known as cognitive enhancement therapy, which focuses on social cognition as well as neurocognition, has shown efficacy.

Family Therapy or Education, which addresses the whole family system of an individual with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, has been consistently found to be beneficial, at least if the duration of intervention is longer-term. Aside from therapy, the impact of schizophrenia on families and the burden on carers has been recognized, with the increasing availability of self-help books on the subject. There is also some evidence for benefits from social skills training, although there have also been significant negative findings. Some studies have explored the possible benefits of music therapy and other creative therapies.

The Soteria model is alternative to inpatient hospital treatment using a minimal medication approach. It is described as a milieu-therapeutic recovery method, characterized by its founder as "the 24 hour a day application of interpersonal phenomenologic interventions by a nonprofessional staff, usually without neuroleptic drug treatment, in the context of a small, homelike, quiet, supportive, protective, and tolerant social environment." Although research evidence is limited, a 2008 systematic review found the programme equally as effective as treatment with medication in people diagnosed with first and second episode schizophrenia.

Other

Electroconvulsive therapy is not considered a first line treatment but may be prescribed in cases where other treatments have failed. It is more effective where symptoms of catatonia are present, and is recommended for use under NICE guidelines in the UK for catatonia if previously effective, though there is no recommendation for use for schizophrenia otherwise. Psychosurgery has now become a rare procedure and is not a recommended treatment for schizophrenia.

Service-user led movements have become integral to the recovery process in Europe and America; groups such as the Hearing Voices Network and the Paranoia Network have developed a self-help approach that aims to provide support and assistance outside the traditional medical model adopted by mainstream psychiatry. By avoiding framing personal experience in terms of criteria for mental illness or mental health, they aim to destigmatize the experience and encourage individual responsibility and a positive self-image. Partnerships between hospitals and consumer-run groups are becoming more common, with services working toward remediating social withdrawal, building social skills and reducing rehospitalization.

Prognosis

Course

The International Study of Schizophrenia (ISoS), coordinated by the World Health Organization, carried out a long-term follow-up study of 1633 individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia around the world. Outcome after 10 and 15 years varied substantially between individuals and countries. Overall over half of those available for follow-up had recovered in terms of symptomology ( Bleuler Scale of 4) and over a third on combined symptomology and good functioning ( GAF greater than 60). Around one sixth of those were "judged as having achieved complete recovery, in the sense of no longer requiring any form of treatment", although some still had some level of symptomology or disability. There was significant "late recovery" even after continued problems and treatment failures. It was concluded that: "the ISoS findings join others in relieving patients, carers and clinicians of the chronicity paradigm which dominated thinking throughout much of the 20th century."

A review of major longitudinal studies in North America also found large variation in outcomes, and that the course could be mild, moderate, or severe. Outcome was on average worse than for other psychotic and psychiatric disorders, but between 21% and 57% showed good outcome, depending on the strictness of the criteria used. "Very few" showed a deteriorating course, although the danger of suicide and early death was indicated. It was noted that: "Of central importance, there is now evidence that a moderate number of schizophrenia patients do have complete symptomatic remissions without further relapses, at least for a good period of time, and that some of these patients may not require maintenance medication."

A clinical study using strict recovery criteria (concurrent remission of positive and negative symptoms and adequate social and vocational functioning continuously for two years) found a recovery rate of 14% within the first five years. A 5-year community study found that 62% showed overall improvement on a composite measure of symptomatic, clinical and functional outcomes.

An important additional finding from the World Health Organization studies was that individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia have much better long-term outcomes in " developing countries" (India, Colombia and Nigeria) than in " developed countries" (USA, UK, Ireland, Denmark, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Japan, and Russia), despite the fact antipsychotic drugs are typically not widely available in poorer countries.

Defining recovery

Rates are not always comparable across studies because exact definitions of remission and recovery have not been widely established. A "Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group" has proposed standardized remission criteria involving "improvements in core signs and symptoms to the extent that any remaining symptoms are of such low intensity that they no longer interfere significantly with behaviour and are below the threshold typically utilized in justifying an initial diagnosis of schizophrenia." Standardized recovery criteria have also been proposed by a number of different researchers, with the stated DSM definitions of a "complete return to premorbid levels of functioning” or "complete return to full functioning" seen as inadequate, impossible to measure, incompatible with the variability in how society defines normal psychosocial functioning, and contributing to self-fullfilling pessimism and stigma. Some mental health professionals may have quite different basic perceptions and concepts of recovery than individuals with the diagnosis, including those in the consumer/survivor movement. One notable limitation of nearly all the research criteria is failure to address the person's own evaluations and feelings about their life. Schizophrenia and recovery often involve a continuing loss of self-esteem, alienation from friends and family, interruption of school and career, and social stigma, "experiences that cannot just be reversed or forgotten." An increasingly influential model defines recovery as a process, similar to being "in recovery" from drug and alcohol problems, and emphasizes a personal journey involving factors such as hope, choice, empowerment, social inclusion and achievement.

Predictors

Several factors have been associated with a better overall prognosis: Being female, acute (vs. insidious) onset of symptoms, older age of first episode, predominantly positive (rather than negative) symptoms, presence of mood symptoms, and good pre-illness functioning. The strengths and internal resources of the individual concerned, such as determination or " psychological resilience", have also been associated with better prognosis. The attitude and level of support from people in the individual's life can have a significant impact; research framed in terms of the negative aspects of this - the level of critical comments, hostility, and intrusive or controlling attitudes (termed high ' Expressed emotion' by researchers) - has consistently indicated links to relapse. Most research on predictive factors is correlational in nature, however, and a clear cause-and-effect relationship is often difficult to establish.

Mortality

In a study of over 168,000 Swedish citizens undergoing psychiatric treatment, schizophrenia was associated with an average life expectancy of approximately 80–85% of that of the general population. Women with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were found to have a slightly better life expectancy than that of men, and as a whole, a diagnosis of schizophrenia was associated with a better life expectancy than substance abuse, personality disorder, heart attack and stroke. Other identified factors include smoking, poor diet, little exercise and the negative health effects of psychiatric drugs.

There is a higher than average suicide rate associated with schizophrenia. The psychiatric literature typically states that the proportion is 10%, but a more recent analysis of studies and statistics gives an estimate of 4.9%, most often occuring in the period following first hospital admission/onset. Several times more attempt suicide. There are a variety of reasons and risk factors.

Violence

The relationship between violent acts and schizophrenia is a contentious topic. Current research indicates that the percentage of people with schizophrenia who commit violent acts is higher than the percentage of people without any disorder, but lower than is found for disorders such as alcoholism, and the difference is reduced or not found in same-neighbourhood comparisons when related factors are taken into account, notably sociodemographic variables and substance misuse. Studies have indicated that 5% to 10% of those charged with murder in Western countries have a schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

The occurrence of psychosis in schizophrenia has sometimes been linked to a higher risk of violent acts. Findings on the specific role of delusions or hallucinations have been inconsistent, but have focused on delusional jealousy, perception of threat and command hallucinations. It has been proposed that a certain type of individual with schizophrenia may be most likely to offend, characterized by a history of educational difficulties, low IQ, conduct disorder, early-onset substance misuse and offending prior to diagnosis.

A consistent finding is that individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia are often the victims of violent crime—at least 14 times more often than they are perpetrators. Another consistent finding is a link to substance misuse, particularly alcohol, among the minority who commit violent acts. Violence by or against individuals with schizophrenia typically occurs in the context of complex social interactions within a family setting, and is also an issue in clinical services and in the wider community.

Screening and prevention

There are no reliable markers for the later development of schizophrenia although research is being conducted into how well a combination of genetic risk plus non-disabling psychosis-like experience predicts later diagnosis. People who fulfill the 'ultra high-risk mental state' criteria, that include a family history of schizophrenia plus the presence of transient or self-limiting psychotic experiences, have a 20–40% chance of being diagnosed with the condition after one year. The use of psychological treatments and medication has been found effective in reducing the chances of people who fulfill the 'high-risk' criteria from developing full-blown schizophrenia. However, the treatment of people who may never develop schizophrenia is controversial, in light of the side-effects of antipsychotic medication; particularly with respect to the potentially disfiguring tardive dyskinesia and the rare but potentially lethal neuroleptic malignant syndrome. The most widely used form of preventative health care for schizophrenia takes the form of public education campaigns that provide information on risk factors, early detection and treatment options.

Alternative approaches

An approach broadly known as the anti-psychiatry movement, most active in the 1960s, opposes the orthodox medical view of schizophrenia as an illness. Psychiatrist Thomas Szasz argued that psychiatric patients are not ill, but rather individuals with unconventional thoughts and behaviour that make society uncomfortable. He argues that society unjustly seeks to control them by classifying their behaviour as an illness and forcibly treating them as a method of social control. According to this view, "schizophrenia" does not actually exist but is merely a form of social construction, created by society's concept of what constitutes normality and abnormality. Szasz has never considered himself to be "anti-psychiatry" in the sense of being against psychiatric treatment, but simply believes that treatment should be conducted between consenting adults, rather than imposed upon anyone against his or her will. Similarly, psychiatrists R. D. Laing, Silvano Arieti, Theodore Lidz and Colin Ross have argued that the symptoms of what is called mental illness are comprehensible reactions to impossible demands that society and particularly family life places on some sensitive individuals. Laing, Arieti, Lidz and Ross were notable in valuing the content of psychotic experience as worthy of interpretation, rather than considering it simply as a secondary and essentially meaningless marker of underlying psychological or neurological distress. Laing described eleven case studies of people diagnosed with schizophrenia and argued that the content of their actions and statements was meaningful and logical in the context of their family and life situations. In 1956, Palo Alto, Gregory Bateson and his colleagues Paul Watzlawick, Donald Jackson, and Jay Haley articulated a theory of schizophrenia, related to Laing's work, as stemming from double bind situations where a person receives different or contradictory messages. Madness was therefore an expression of this distress and should be valued as a cathartic and trans-formative experience. In the books Schizophrenia and the Family and The Origin and Treatment of Schizophrenic Disorders Lidz and his colleagues explain their belief that parental behaviour can result in mental illness in children. Arieti's Interpretation of Schizophrenia won the 1975 scientific National Book Award in the United States.

The concept of schizophrenia as a result of civilization has been developed further by psychologist Julian Jaynes in his 1976 book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind; he proposed that until the beginning of historic times, schizophrenia or a similar condition was the normal state of human consciousness. This would take the form of a " bicameral mind" where a normal state of low affect, suitable for routine activities, would be interrupted in moments of crisis by "mysterious voices" giving instructions, which early people characterized as interventions from the gods. Researchers into shamanism have speculated that in some cultures schizophrenia or related conditions may predispose an individual to becoming a shaman; the experience of having access to multiple realities is not uncommon in schizophrenia, and is a core experience in many shamanic traditions. Equally, the shaman may have the skill to bring on and direct some of the altered states of consciousness psychiatrists label as illness. Psychohistorians, on the other hand, accept the psychiatric diagnoses. However, unlike the current medical model of mental disorders they argue that poor parenting in tribal societies causes the shaman's schizoid personalities. Speculation regarding primary and important religious figures as having schizophrenia abound. Commentators such as Paul Kurtz and others have endorsed the idea that major religious figures experienced psychosis, heard voices and displayed delusions of grandeur.

Psychiatrist Tim Crow has argued that schizophrenia may be the evolutionary price we pay for a left brain hemisphere specialization for language. Since psychosis is associated with greater levels of right brain hemisphere activation and a reduction in the usual left brain hemisphere dominance, our language abilities may have evolved at the cost of causing schizophrenia when this system breaks down.

Alternative medical treatments

A branch of alternative medicine that deals with schizophrenia is known as orthomolecular psychiatry. Orthomolecular psychiatry considers the schizophrenias to be a group of disorders; management entails performing the appropriate diagnostic tests and then providing the appropriate therapy. Vitamin B-3 ( Niacin) has been proposed as an effective treatment in some cases. The body's adverse reactions to gluten are implicated in some alternative theories; proponents of orthomolecular psychiatric thought claim that an adverse reaction to gluten is involved in the etiology of some cases. This theory—discussed by one author in three British journals in the 1970s—is unproven. A 2006 literature review suggests that gluten may be a factor for patients with celiac disease and for a subset of patients afflicted with schizophrenia, but that further study is needed to conclusively confirm such a link. In a 2004 Israeli study, anti-gluten antibodies were measured in 50 schizophrenic patients and a matched control group. All antibody tests in both groups were negative leading to the conclusion that "it is unlikely that there is an association between gluten sensitivity and schizophrenia." Some researchers suggest that dietary and nutritional treatments may hold promise in the treatment of schizophrenia.

History

Accounts of a schizophrenia-like syndrome are thought to be rare in the historical record prior to the 1800s, although reports of irrational, unintelligible, or uncontrolled behaviour were common. There has been an interpretation that brief notes in the Ancient Egyptian Ebers papyrus may imply schizophrenia, but other reviews have not suggested any connection. A review of ancient Greek and Roman literature indicated that although psychosis was described, there was no account of a condition meeting the criteria for schizophrenia. Bizarre psychotic beliefs and behaviors similar to some of the symptoms of schizophrenia were reported in Arabic medical and psychological literature during the Middle Ages, but no condition resembling schizophrenia was reported in a major Islamic textbook of the 15th Century. Given limited historical evidence, schizophrenia (as prevalent as it is today) may be a modern phenomenon, or alternatively it may have been obscured in historical writings by related concepts such as melancholia or mania.

A detailed case report in 1797 concerning James Tilly Matthews, and accounts by Phillipe Pinel published in 1809, are often regarded as the earliest cases of schizophrenia in the medical and psychiatric literature. Schizophrenia was first described as a distinct syndrome affecting teenagers and young adults by Bénédict Morel in 1853, termed démence précoce (literally 'early dementia'). The term dementia praecox was used in 1891 by Arnold Pick to in a case report of a psychotic disorder. In 1893 Emil Kraepelin introduced a broad new distinction in the classification of mental disorders between dementia praecox and mood disorder (termed manic depression and including both unipolar and bipolar depression). Kraepelin believed that dementia praecox was primarily a disease of the brain, and particularly a form of dementia, distinguished from other forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease, which typically occur later in life. Kraepelin's classification slowly gained acceptance. There were objections to the use of the term "dementia" despite cases of recovery, and some defence of diagnoses it replaced such as adolescent insanity.

The word schizophrenia—which translates roughly as "splitting of the mind" and comes from the Greek roots schizein (σχίζειν, "to split") and phrēn, phren- (φρήν, φρεν-, "mind")—was coined by Eugen Bleuler in 1908 and was intended to describe the separation of function between personality, thinking, memory, and perception. Bleuler described the main symptoms as 4 A's: flattened Affect, Autism, impaired Association of ideas and Ambivalence. Bleuler realized that the illness was not a dementia as some of his patients improved rather than deteriorated and hence proposed the term schizophrenia instead.

The term schizophrenia is commonly misunderstood to mean that affected persons have a "split personality". Although some people diagnosed with schizophrenia may hear voices and may experience the voices as distinct personalities, schizophrenia does not involve a person changing among distinct multiple personalities. The confusion arises in part due to the meaning of Bleuler's term schizophrenia (literally "split" or "shattered mind"). The first known misuse of the term to mean "split personality" was in an article by the poet T. S. Eliot in 1933.

In the first half of the twentieth century schizophrenia was considered to be a hereditary defect, and sufferers were subject to eugenics in many countries. Hundreds of thousands were sterilized, with or without consent—the majority in Nazi Germany, the United States, and Scandinavian countries. Along with other people labeled "mentally unfit", many diagnosed with schizophrenia were murdered in the Nazi " Action T4" program.

The diagnostic description of schizophrenia has changed over time. It became clear after the 1971 US-UK Diagnostic Study that schizophrenia was diagnosed to a far greater extent in America than in Europe. This was partly due to looser diagnostic criteria in the US, which used the DSM-II manual, contrasting with Europe and its ICD-9. This was one of the factors in leading to the revision not only of the diagnosis of schizophrenia, but the revision of the whole DSM manual, resulting in the publication of the DSM-III.

Society and culture

Stigma has been identified as a major obstacle in the recovery of patients with schizophrenia. In a large, representative sample from a 1999 study, 12.8% of Americans believed that individuals with schizophrenia were "very likely" to do something violent against others, and 48.1% said that they were "somewhat likely" to. Over 74% said that people with schizophrenia were either "not very able" or "not able at all" to make decisions concerning their treatment, and 70.2% said the same of money management decisions. The perception of individuals with psychosis as violent has more than doubled in prevalence since the 1950s, according to one meta-analysis.

The book and film A Beautiful Mind chronicled the life of John Forbes Nash, a Nobel-Prize-winning mathematician who was diagnosed with schizophrenia. The Marathi film Devrai (Featuring Atul Kulkarni) is a presentation of a patient with schizophrenia. The film, set in the Konkan region of Maharashtra in Western India, shows the behaviour, mentality, and struggle of the patient as well as his loved-ones. It also portrays the treatment of this mental illness using medication, dedication and plenty of patience by the close relatives of the patient. Other factual books have been written by relatives on family members; Australian journalist Anne Deveson told the story of her son's battle with schizophrenia in Tell me I'm Here, later made into a movie.

In Bulgakov's Master and Margarita the poet Ivan Bezdomnyj is institutionalized and diagnosed with schizophrenia after witnessing the devil (Woland) predict Berlioz's death. The book The Eden Express by Mark Vonnegut recounts his struggle with schizophrenia and his recovering journey.