Tamil language

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Languages

| Tamil தமிழ் tamiḻ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation: | [t̪ɐmɨɻ] (Listen) | |||

| Spoken in: | India, Sri Lanka and Singapore, where it has an official status; with significant minorities in Malaysia, Mauritius, and Réunion, and emigrant communities around the world. | |||

| Total speakers: | 68 million native, 77 million total | |||

| Ranking: | 20, 16, 15(native speakers) | |||

| Language family: | Dravidian Southern Tamil-Kannada Tamil-Kodagu Tamil-Malayalam Tamil |

|||

| Writing system: | Vatteluttu | |||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in: | ||||

| Regulated by: | Various academies and the Government of Tamil Nadu | |||

| Language codes | ||||

| ISO 639-1: | ta | |||

| ISO 639-2: | tam | |||

| ISO 639-3: | tam | |||

|

||||

| Tamil is written in a non-Latin script. Tamil text used in this article is transliterated into the Latin script according to the ISO 15919 standard. |

Tamil (தமிழ் tamiḻ; IPA: [t̪ɐmɨɻ]) is a Dravidian language spoken predominantly by Tamils in India, Sri Lanka and Singapore where it has an official status; with significant minorities in Malaysia, Mauritius, and Réunion, and emigrant communities around the world. It is the official language of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, classical language in India, and has official status in India , Sri Lanka and Singapore. With more than 77 million speakers, Tamil is one of the widely spoken languages in the world.

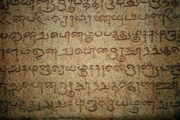

Tamil has a known literary tradition of over two thousand years. The earliest epigraphic records found date to around 300 BC and the Tolkāppiyam (தொல்காப்பியம்), oldest known treatise in Tamil, has been dated variously between second century BC and tenth century AD. Tamil was declared a classical language of India by the Government of India in 2004 and was the first Indian language to have been accorded the status.

Tamil employs agglutinative grammar, where suffixes are used to mark noun class, number, and case, verb tense and other grammatical categories. Unlike other Dravidian languages, the metalanguage of Tamil, the language used to describe the technical linguistic terms of the language and its structure, is also Tamil (rather than Sanskrit). According to a 2001 survey, there were 1,863 newspapers published in Tamil, of which 353 were dailies.

History

Tamil is one of the ancient languages of the world with a 2200 year history. The origins of Tamil are not transparent, but it developed and flourished in India as an independent language with a rich literature. More than 55% of the epigraphical inscriptions, about 55,000, found by the Archaeological Survey of India in India are in Tamil language Unlike the neighbouring Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh where early inscriptions were written in Sanskrit, the early inscriptions in Tamil Nadu used Tamil exclusively. Tamil has the oldest extant literature amongst the Dravidian languages, but dating the language and the literature precisely is difficult. Literary works in India were preserved either in palm leaf manuscripts (implying repeated copying and recopying) or through oral transmission, making direct dating impossible. External chronological records and internal linguistic evidence, however, indicate that the oldest extant works were probably compiled sometime between the 2nd century BC and the 10th century AD.

Epigraphic attestation of Tamil begins with rock inscriptions from the 2nd century BC, written in Tamil-Brahmi, an adapted form of the Brahmi script. The earliest extant literary text is the Tolkāppiyam, a work on poetics and grammar which describes the language of the classical period, dated variously between the 1st BC and 10th AD.

Tamil scholars categorise the Tamil literature and language into the following periods:

- Sangam (100 BC to 300 AD)

- Post-Sangam period (300 to 600 CE)

- Bhakthi period (600 to 1200 CE)

- Mediaeval Period (1200 to 1800 CE)

- Modern (1800 to the present)

The Sangam literature contains about 50,000 lines of poetry contained in 2381 poems attributed to 473 poets including many women poets. Many of the poems of Sangam period were also set to music. During the post-Sangam period, important works like Thirukkural, and epic poems like Silappatikaram, Manimekalai, Sīvakacintāmani were composed. The Bhakthi period is known for the great outpouring of devotional songs set to pann music. Of those 9,295 Tevaram songs on Saivism and 4,000 songs on Vaishnavism are well known. The early mediaeval Period gave rise to one of the best known adaptations of the Ramayana in Tamil, known as Kamba Ramayanam and a story of 63 Nayanmars known as Periyapuranam.

Origin and development

Tamil belongs to the southern branch of the Dravidian languages. It is sometimes classified as being part of a Tamil language family, which alongside Tamil proper, also includes the languages of about 35 ethno-linguistic groups such as the Irula, and Yerukula languages (see SIL Ethnologue). This group is a subgroup of the Tamil-Malayalam languages, which falls under a subgroup of the Tamil-Kodagu languages, which in turn is a subgroup of the Tamil-Kannada languages. The closest major relative of Tamil is Malayalam which is explained by the fact that until about the ninth century, Tamil and Malayalam were dialects of one language, called "Tamil" by the speakers of both. Although many of the differences between Tamil and Malayalam evidence a pre-historic split between eastern and western dialects, the process of separation of the two into distinct languages was not completed until sometime in the 13th or 14th century.

The origins and initial development of Tamil is similar to that of the other Dravidian languages and independent of Sanskrit. During later centuries, however, Tamil, along with other Dravidian languages like Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam etc., has been greatly influenced by Sanskrit in terms of vocabulary, grammar and literary styles. A number of Sanskrit loan words were also absorbed by Tamil during this period, reflecting the increased trend of Sanskritisation in the Tamil country. A number of authors of the late mediaeval period tried to resist this trend, culminating in the puristic movement of the 20th century, led by Parithimaar Kalaignar and Maraimalai Adigal, which sought to remove the accumulated influence of Sanskrit on Tamil. This movement was called taṉit tamiḻ iyakkam (meaning pure Tamil movement). As a result of this, Tamil in formal documents, public speeches and scientific discourses is largely free of Sanskrit loan words and it is estimated that the number of Sanskrit loan words in Tamil may actually have come down from about 50% to 20%.

Geographic distribution

Tamil is the first language of the majority in Tamil Nadu, India and North Eastern Province, Sri Lanka. The language is spoken by small groups of minorities in other parts of these two countries such as Karnataka, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Manipur and Maharashtra in case of India and Colombo and the hill country in case of Sri Lanka.

There are currently sizeable Tamil-speaking populations descended from colonial-era migrants in Malaysia, Singapore, Burma, South Africa, and Mauritius. Many people in Guyana, Fiji, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago have Tamil origins, but only a small number speak the language there. Groups of more recent migrants from Sri Lanka and India exist in Canada (especially Toronto), USA, Australia, many Middle Eastern countries, and most of the western European countries.

Legal status

Tamil is the official language of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Tamil is one of the official languages of the union territories of Pondicherry and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands It is one of 23 nationally recognised languages in the Constitution of India. Tamil is also one of the official languages of Sri Lanka and Singapore. In Malaysia, primary education in government schools is also available fully in Tamil.

In addition, with the creation in 2004 of a legal status for classical languages by the government of India and following a political campaign supported by several Tamil associations Tamil became the first legally recognised Classical language of India. The recognition was announced by the then President of India, Dr. Abdul Kalam, in a joint sitting of both houses of the Indian Parliament on June 6, 2004.

Dialects

Tamil is a diglossic language. Tamil dialects are mainly differentiated from each other by the fact that they have undergone different phonological changes and sound shifts in evolving from Old Tamil. For example, the word for "here" —iṅku in Centamil (the classic variety)—has evolved into iṅkū in the Kongu dialect of Coimbatore, inga in the dialect of Thanjavur, and iṅkai in some dialects of Sri Lanka. Old Tamil's iṅkaṇ (where kaṇ means place) is the source of iṅkane in the dialect of Tirunelveli, Old Tamil iṅkaṭṭu is the source of iṅkuṭṭu in the dialect of Ramanathapuram, and iṅkaṭe in various northern dialects. Even now in Coimbatore area it is common to hear "akkaṭṭa" meaning "that place".

Although Tamil dialects do not differ significantly in their vocabulary, there are a few exceptions. The dialects spoken in Sri Lanka retain many words and grammatical forms that are not in everyday use in India, and use many other words slightly differently. The dialect of the of Palakkad in kerala has a large number of Malayalam loanwords, has also been influenced by Malayalam syntax and also has a distinct Malayalam accent. Hebbar and Mandyam dialects, spoken by groups of Tamil Vaishnavites who migrated to Karnataka in the eleventh century, retain many features of the Vaishnava paribasai, a special form of Tamil developed in the ninth and tenth centuries that reflect Vaishnavite religious and spiritual values. Several castes have their own sociolects which most members of that caste traditionally used regardless of where they come from. It is often possible to identify a person’s caste by their speech.

Spoken and literary variants

In addition to its various dialects, Tamil exhibits different forms: a classical literary style modelled on the ancient language (caṅkattamiḻ), a modern literary and formal style (centamiḻ), and a modern colloquial form (koṭuntamiḻ). These styles shade into each other, forming a stylistic continuum. For example, it is possible to write centamiḻ with a vocabulary drawn from caṅkattamiḻ, or to use forms associated with one of the other variants while speaking koṭuntamiḻ.

In modern times, centamiḻ is generally used in formal writing and speech. For instance, it is the language of textbooks, of much of Tamil literature and of public speaking and debate. In recent times, however, koṭuntamiḻ has been making inroads into areas that have traditionally been considered the province of centamiḻ. Most contemporary cinema, theatre and popular entertainment on television and radio, for example, is in koṭuntamiḻ, and many politicians use it to bring themselves closer to their audience. The increasing use of koṭuntamiḻ in modern times has led to the emergence of unofficial ‘standard’ spoken dialects. In India, the ‘standard’ koṭuntamiḻ is based on ‘educated non-brahmin speech’, rather than on any one dialect, but has been significantly influenced by the dialects of Thanjavur and Madurai. In Sri Lanka the standard is based on the dialect of Jaffna.

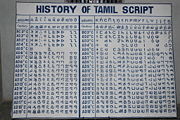

Writing system

Tamil is written using a script called the vaṭṭeḻuttu. The Tamil script consists of 12 vowels, 18 consonants and one special character, the āytam. The vowels and consonants combine to form 216 compound characters, giving a total of 247 characters. As with other Indic scripts, all consonants have an inherent vowel a, which in Tamil, is removed by adding an overdot called a puḷḷi, to the consonantal sign. Unlike most Indic scripts, the Tamil script does not distinguish between voiced and unvoiced plosives. Instead, plosives are articulated with voice or unvoiced depending on their position in a word, in accordance with the rules of Tamil phonology, as discussed below.

In addition to the standard characters, six characters taken from the Grantha script, which was used in the Tamil region to write Sanskrit, are sometimes used to represent sounds not native to Tamil, that is, words borrowed from Sanskrit, Prakrit and other languages. The traditional system of writing loan-words, which involved respelling them in accordance with Tamil phonology remains.

Sounds

Tamil phonology is characterised by the presence of retroflex consonants, and strict rules for the distribution within words of voiced and unvoiced plosives. Tamil phonology permits few consonant clusters, which can never be word initial. Native grammarians classify Tamil phonemes into vowels, consonants, and a "secondary character", the āytam.

Vowels

Tamil vowels are called uyireḻuttu (uyir – life, eḻuttu – letter). The vowels are classified into short (kuṟil) and long (five of each type) and two diphthongs, /ai/ and /au/, and three "shortened" (kuṟṟiyal) vowels.

The long (neṭil) vowels are about twice as long as the short vowels. The diphthongs are usually pronounced about 1.5 times as long as the short vowels, though most grammatical texts place them with the long vowels.

| Short | Long | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | Front | Central | Back | |

| Close | i | u | iː | uː | ||

| இ | உ | ஈ | ஊ | |||

| Mid | e | o | eː | oː | ||

| எ | ஒ | ஏ | ஓ | |||

| Open | a | (æː) | aː | (ɔː) | ||

| அ | ஐ | ஆ | ஒள | |||

Consonants

Tamil consonants are known as meyyeḻuttu (mey—body, eḻuttu—letters). The consonants are classified into three categories with six in each category: valliṉam—hard, melliṉam—soft or Nasal, and iṭayiṉam—medium.

Unlike most Indian languages, Tamil does not have aspirated consonants. In addition, the voicing of plosives is governed by strict rules in centamiḻ. Plosives are unvoiced if they occur word-initially or doubled. Elsewhere they are voiced, with a few becoming fricatives intervocalically. Nasals and approximants are always voiced.

A chart of the Tamil consonant phonemes in the International Phonetic Alphabet follows:

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p (b) | t̪ (d̪) | ʈ (ɖ) | tʃ (dʒ) | k (g) | |

| ப | த | ட | ச | க | ||

| Nasal | m | n̪ | ṉ | ɳ | ɲ | ŋ |

| ம | ந | ன | ண | ஞ | ங | |

| Rhotic | ɾ̪ | r | ||||

| ர | ற | |||||

| Lateral | l̪ | ɭ | ||||

| ல | ள | |||||

| Approximant | ʋ | ɻ | j | |||

| வ | ழ | ய |

Phonemes in brackets are voiced equivalents. Both voiceless and voiced forms are represented by the same character in Tamil, and voicing is determined by context. The sounds /f/ and /ʂ/ are peripheral to the phonology of Tamil, being found only in loanwords and frequently replaced by native sounds. There are well-defined rules for elision in Tamil categorised into different classes based on the phoneme which undergoes elision.

Aytam

Classical Tamil also had a phoneme called the āytam, written as ‘ஃ’. Tamil grammarians of the time classified it as a dependent phoneme (or restricted phoneme ) (cārpeḻuttu), but it is very rare in modern Tamil. The rules of pronunciation given in the Tolkāppiyam, a text on the grammar of Classical Tamil, suggest that the āytam could have glottalised the sounds it was combined with. It has also been suggested that the āytam was used to represent the voiced implosive (or closing part or the first half) of geminated voiced plosives inside a word.

Grammar

Much of Tamil grammar is extensively described in the oldest known grammar book for Tamil, the Tolkāppiyam. Modern Tamil writing is largely based on the 13th century grammar Naṉṉūl which restated and clarified the rules of the Tolkāppiyam, with some modifications. Traditional Tamil grammar consists of five parts, namely eḻuttu, col, poruḷ, yāppu, aṇi. Of these, the last two are mostly applied in poetry.

Similar to other Dravidian languages, Tamil is an agglutinative language. Tamil is characterised by its use of retroflex consonants, like the other Dravidian languages. It also uses a liquid l (ழ) (example Tamil), which is also found in Malayalam (example Kozhikode), but disappeared from Kannada at around 1000 AD (but present in Unicode), and was never present in Telugu. Tamil words consist of a lexical root to which one or more affixes are attached. Most Tamil affixes are suffixes. Tamil suffixes can be derivational suffixes, which either change the part of speech of the word or its meaning, or inflectional suffixes, which mark categories such as person, number, mood, tense, etc. There is no absolute limit on the length and extent of agglutination, which can lead to long words with a large number of suffixes.

Morphology

Tamil nouns (and pronouns) are classified into two super-classes (tiṇai)—the "rational" (uyartiṇai), and the "irrational" (aḵṟiṇai)—which include a total of five classes (pāl, which literally means ‘gender’). Humans and deities are classified as "rational", and all other nouns (animals, objects, abstract nouns) are classified as irrational. The "rational" nouns and pronouns belong to one of three classes (pāl)—masculine singular, feminine singular, and rational plural. The "irrational" nouns and pronouns belong to one of two classes - irrational singular and irrational plural. The pāl is often indicated through suffixes. The plural form for rational nouns may be used as an honorific, gender-neutral, singular form.

Suffixes are used to perform the functions of cases or postpositions. Traditional grammarians tried to group the various suffixes into eight cases corresponding to the cases used in Sanskrit. These were the nominative, accusative, dative, sociative, genitive, instrumental, locative, and ablative. Modern grammarians argue that this classification is artificial, and that Tamil usage is best understood if each suffix or combination of suffixes is seen as marking a separate case. Tamil nouns can take one of four prefixes, i, a, u and e which are functionally equivalent to the demonstratives in English.

Tamil verbs are also inflected through the use of suffixes. A typical Tamil verb form will have a number of suffixes, which show person, number, mood, tense and voice.

- Person and number are indicated by suffixing the oblique case of the relevant pronoun. The suffixes to indicate tenses and voice are formed from grammatical particles, which are added to the stem.

- Tamil has two voices. The first indicates that the subject of the sentence undergoes or is the object of the action named by the verb stem, and the second indicates that the subject of the sentence directs the action referred to by the verb stem.

- Tamil has three simple tenses—past, present, and future—indicated by the suffixes, as well as a series of perfects indicated by compound suffixes. Mood is implicit in Tamil, and is normally reflected by the same morphemes which mark tense categories. Tamil verbs also mark evidentiality, through the addition of the hearsay clitic ām.

Traditional grammars of Tamil do not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs, including both of them under the category uriccol, although modern grammarians tend to distinguish between them on morphological and syntactical grounds.

Tamil has no articles. Definiteness and indefiniteness are either indicated by special grammatical devices, such as using the number "one" as an indefinite article, or by the context. In the first person plural, Tamil makes a distinction between inclusive pronouns நாம் nām (we), நமது namatu (our) that include the addressee and exclusive pronouns நாங்கள் nāṅkaḷ (we), எமது ematu (our) that do not.

Syntax

Tamil is a consistently head-final language. The verb comes at the end of the clause, with typical word order Subject Object Verb (SOV). However, Tamil also exhibits extensive scrambling (word order variation), so that surface permutations of the SOV order are possible with different pragmatic effects. Tamil has postpositions rather than prepositions. Demonstratives and modifiers precede the noun within the noun phrase. Subordinate clauses precede the verb of the matrix clause.

Tamil is a null subject language. Not all Tamil sentences have subjects, verbs and objects. It is possible to construct valid sentences that have only a verb—such as muṭintuviṭṭatu ("completed")—or only a subject and object, without a verb such as atu eṉ vīṭu ("That, my house"). Tamil does not have a copula (a linking verb equivalent to the word is). The word is included in the translations only to convey the meaning more easily.

Vocabulary

A strong sense of linguistic purism is found in Modern Tamil. Much of the modern vocabulary derives from classical Tamil, as well as governmental and non-governmental institutions, such as the Tamil Virtual University, and Annamalai University.

These institutions have generated technical dictionaries for Tamil containing neologisms and words derived from Tamil roots to replace loan words from English and other languages. Since mediaeval times, there has been a strong resistance to the use of Sanskrit words in Tamil. As a result, the Prakrit and Sanskrit loan words used in modern Tamil are, unlike in some other Dravidian languages, restricted mainly to some spiritual terminology and abstract nouns. Besides Sanskrit, there are a few loan words from Persian and Arabic implying there were trade ties in ancient times. Many loan words from Portuguese and Dutch and English were introduced into colloquial and written Tamil during the colonial period.

Words of Tamil origin occur in other languages. Popular examples in English are cash (kaasu, meaning "money"), cheroot (curuṭṭu meaning "rolled up"), mango (from mangai), mulligatawny (from miḷaku taṉṉir meaning pepper water), pariah (from paraiyar), ginger (from ingi), curry (from kari), rice (from arici) and catamaran (from kaṭṭu maram, கட்டு மரம், meaning "bundled logs"), pandal (shed, shelter, booth), tyer (curd), coir (rope).