We killed Instagram. And we’ll kill the next social media beast, too.

In 2010, we were given a platform that did relatively few things: You could edit photos and post them on a grid, and your friends could comment on them. Even then we wanted it to change. We wanted DMs and Instagram Stories and more editing options and better search and an explore page. Tech executives wanted us addicted to it, wanted us to crave it, wanted it to be a necessary tool in our everyday social existence so advertisers would be able to reach us and Mark Zuckerberg could get another electric hydrofoil surfboard. As the app expanded to incorporate all of those desires, we turned into Violet Beauregarde, rolling around the floor, livid that the platform we’d begged to change had changed too much. If the expression “take a bad thing and make it worse” had no meaning, Meta’s existence alone would afford it one.

Hating Instagram is also as integral to the platform’s existence as being able to post a photo. Like senior Vox reporter Rebecca Jennings wrote in The Goods: “Being mad at Instagram is sort of like being mad at the president: Venting your frustrations about it is both a cathartic and logical response to a seemingly insurmountable problem, the problem of too much power in the hands of too few people.”

But over the past few weeks, what started as a complaint a decade ago has become a chorus of fury. Users are tired of Instagram and its parent company Meta copying the features of other apps. First it was Snapchat, and now it’s TikTok and BeReal — a social media platform with the explicit intent of being more realistic than Instagram that consistently falls short of doing so. In an effort to replicate these apps’ successes, the latest Instagram and Facebook updates simply exhausted users by, among other things, prioritizing “recommended” videos from creators you don’t care about, shoving incessant ads and sponsored content in front of our eyes, and trying out expanded posts that take up more space on our screens. Photographer Tati Bruening made a post demanding that we “Make Instagram Instagram Again.” It was shared by some of the platform’s most powerful users, including Kim Kardashian and Kylie Jenner. The post has more than 2.25 million likes, and the coordinated change.org petition has nearly 300,000 signatures.

Adam Mosseri, the head of Instagram, addressed the criticism in a video, and in an interview with tech reporter Casey Newton, he said Instagram would phase out a TikTok-y redesign and temporarily show users fewer “recommended” videos in the feed. But that change is only temporary, and by the end of 2023, Zuckerberg said that the number of “recommended” posts on Instagram will more than double.

The trouble with an abundant audience

In the early days of social media, we used the platforms to “have fun and be ridiculous and post stuff for what you probably understood to be a limited audience,” Aimée Morrison, an associate professor in the department of English language and literature at the University of Waterloo, told Mashable. Our friends saw our posts, but that was about it.

“The content was abundant, but the audience was not abundant. You imagined that nobody was interested,” Morrison said. Social media has gotten a lot more noxious since then. “Now anyone is like one Google search away from, ‘Oh my God.'” You’re one Google search away from being fired from your teaching job for posting a picture of yourself drinking alcohol, one post away from forever having to relive what you thought was funny at 13 years old, or even one post away from fame.

Before, there was content in abundance, but there was not self-consciousness in abundance.

I find myself missing the internet before the audience — the world in which we would go out to a party and someone would bring their shitty digital camera, and we would take 40 pictures, and every single terrible one would be posted to a Facebook album; a world in which I would write “miss you babe!” on my friends’ wall a moment after she left my house. I miss the freedom of being seen only by my immediate friend group, and the freedom of not being forced to conform to an aesthetic that would grow to form not only who we are but what we buy, where we travel, who our friends are, and what our jobs are (or aren’t).

“We’re always in some ways curating the version of ourselves that we are presenting,” Morrison said. “Before, there was content in abundance, but there was not self-consciousness in abundance. It was more carefree, and we weren’t thinking about all the possible audiences, the revenue opportunities, or the firing opportunities. We were heedless of consequence in ways that ultimately we had to give up, because the real world always comes for our social media eventually.”

A world ruled by the algorithm

As a human teenager, I do remember fearing how the setup of my MySpace Top 8 could affect the IRL interactions I had with my friends. But nothing has ever felt quite as taxing as maintaining the humiliating facade that life online requires of us: the performative nature of posting anything, not being sure what the rules are for post frequency, and dissecting the internal need to share with strangers. Any of the carefreeness of social media has been ripped away from us; there’s a certain ignominy of being online today.

In part, that’s because we’ve moved away from the social media of abundance, “when people would post 50 photos from one night out and then 20 people would respond with inside jokes,” as McSweeney’s editor Lucy Huber labeled it on Twitter. Now we’re moving toward social media not led by connecting with friends and family, but by algorithmic code. We only post once a year, with massive life updates, because our feed is no longer meant to remember a fun night out; it’s meant to entertain us.

Recommendation media, a term coined by Angel investor and Anchor co-founder Michael Mignano, is what you see when you open the ForYou page on TikTok or the explore page on Instagram. You’re being fed content selected specifically for you by an algorithm that will make you stay on the app longer. In comparison, social media of abundance had virtually no algorithmic influence. BeReal is trying to bring that kind of experience back, but with less abundance (you can only post one photo a day). And even an app created with the explicit goal of overthrowing the algorithm overlords is weakened by the same pitfalls as its predecessors: Users plan their posts ahead of time and they crop out the mess.

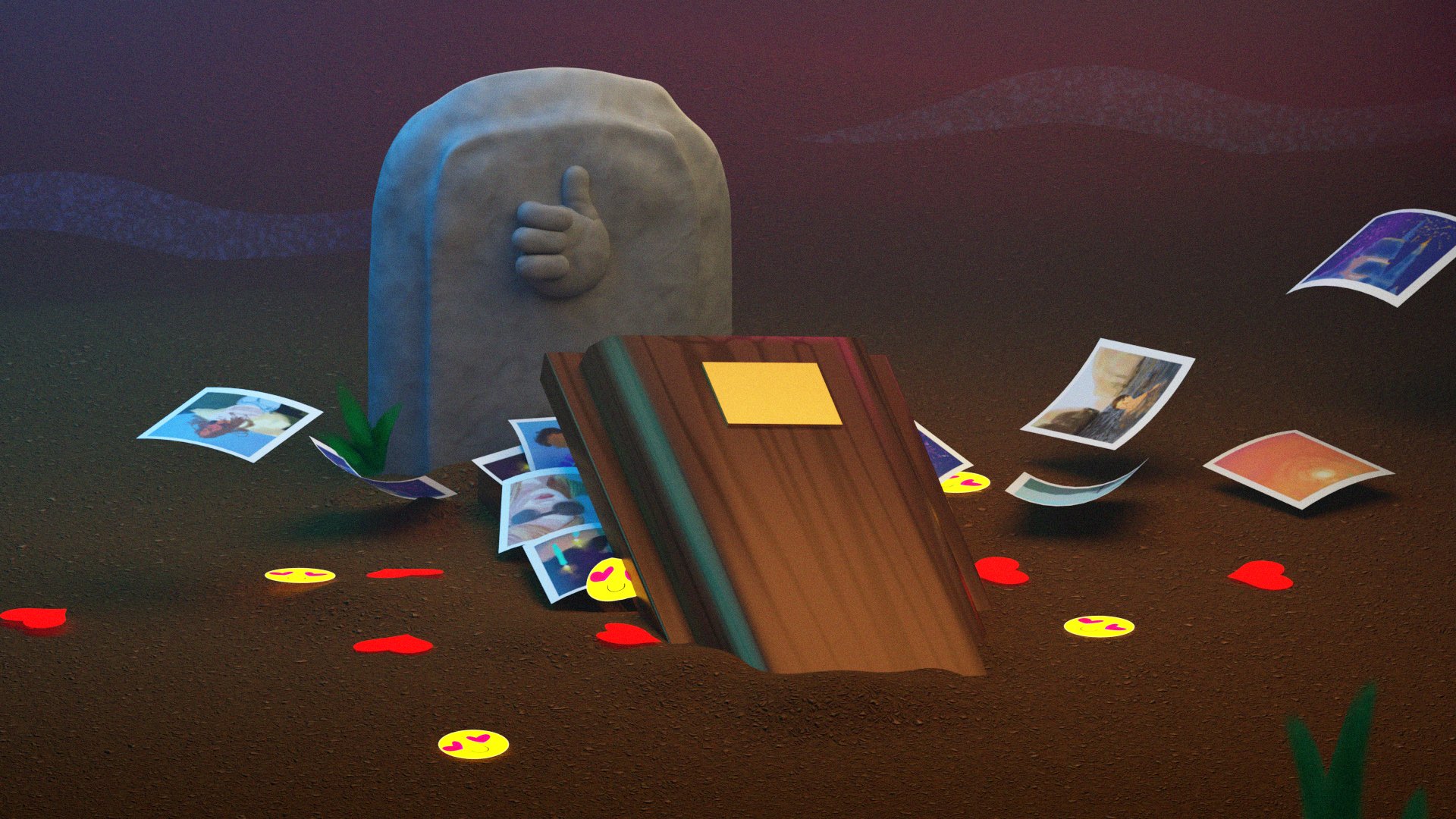

Recommendation media was never meant to be a place for connection; it was intended to provide a space for exploration, innovation, and knowledge, but it has somehow thwarted all three and left us craving our dearly departed social media of abundance. So, I went searching for her. I wanted to find where the social media of abundance lay, and asked her how she died, Pushing Daisies style. But when I finally asked her who killed her, she croaked out one slimy word: greed.

The perpetual cycle of social media hell

During the startup, venture capital phase of a social media platform, Morrison says the most important thing is user growth, which incentivizes platforms to build something that users actually like. But the platform is being built off of “imaginary money,” because it comes from venture capital, which will eventually run out.

“Once you hit a certain threshold of users and ubiquity and you think people are invested in your site, you start to run ads and you start to farm data from your users,” Morrison said.

When we first start using a platform, we get validation from likes, comments, and follows from our friends, which incentivizes us to use it more. Sabrina R. Merritt, the founder and CEO of October Social Media, told Mashable that Meta saw that and ran with it.

Once money enters the room, the art gets impacted.

“The algorithm always changes when the focus becomes about money and using advertising as a source of said revenue,” Merritt said. “That’s the business model of social: to have an algorithm in the beginning that is rewarding to all, and then once you have all the users and you’ve gotten people addicted to using the app on an ongoing basis, the model changes.”

So platforms start bringing in revenue via ads, and “the most effective way to do that is to start to decrease the organic reach that’s happening for users,” Merritt said. “Once money enters the room, the art gets impacted.”

People are brands, and everything sucks

In 2010, in the beginning of Instagram, we posted all the time, and we rarely saw ads. Then ads started taking up space, influencers started producing sponsored content, and eventually we stopped posting on the grid as often with the knowledge that our content wasn’t going to be seen by our friends. We’ve begun viewing more content than we’re sharing while still spending wild amounts of time online.

“You’re competing with brands, you’re competing with influencers and that stuff is generated to go to the top,” Amanda Brennan, a meme librarian and senior director of trends at the digital marketing agency XX Artists, told Mashable.

Now there are new (unofficial) rules of Instagram, according to a TikTok from Mark Plunkett:

-

No filters (few exceptions)

-

Insta stories [are] casual

-

No instagram birthday shout outs

-

Never post on time for a real post (stories too sometimes)

-

Comments mandatory (attendance taken + points for originality)

-

Must respond to all polls

-

Spam accounts + finstas private

Whether you follow those or not, the new rigidity of social media makes us all act as if we’re our own brand. Our aesthetic has to be curated. Everything has to be so slay all the time. Social media has become a job for all of us, and most of us aren’t getting paid.

“Part of the reason why social media doesn’t feel fun is because the communication around it is: ‘You’re a brand. Everyone is their own brand. Everyone is their own television network. You should be making videos,'” Merritt said. “All this pressure to produce not only content but a high level of content in conjunction with living your actual life.”

The future doesn’t look great

Knowing why our social media of abundance is gone, it feels inevitable that we’ll never get her back. We’re existing in a cyclical social media world: We join a platform we love, ruin it, and leave, only to join another platform we love and do the same thing.

“It’s a human, psychological thing,” Morrison said. Tech companies are tapping into a real need we all have for belonging, for community, and for dopamine hits. And they’re exploiting it. As soon as users find what they’re looking for, it’s taken away from them and replaced with revenue avenues for the tech companies, instead.

Eventually we all become aware of being turned into donkeys, and it makes us self-conscious, and we clam up until the next one.

“It’s a startup-to-developed company cycle that’s gonna happen over and over and over again,” Morrison said. “If you are not paying for it, you are the product. And eventually we all become aware of being turned into donkeys, and it makes us self-conscious, and we clam up until the next one.”

Twitter is losing users, fewer people are using Snapchat, and Meta is struggling, too: The company has lost users and hundreds of billions of dollars. I’m not sure where we’ll go from here, if not just a perpetual fall into algorithmic hell. Mignano, the investor who talks about recommendation media, posits that we might see platforms like TikTok and Instagram start making their own content, the same way Netflix and YouTube have. Or perhaps professional media companies like Netflix will start creating social media platforms, given that Netflix’s co-CEO said that his biggest competitors were TikTok and YouTube.

Taking a good thing and making it just a little bit worse is a natural part of the human condition. Think about frozen yogurt in The Good Place or taking air travel from its glamorous past to what is now barefoot, cramped, and led by the whim of TSA agents. Often, going from good to bad to worse is just what we can expect from ourselves. Social media gave us connection, then gave us increased risk for depression, anxiety, and self-harm, all while helping the spread of misinformation. It is only sensible that the same fear-fueled anticipation of watching a horror film might take over our minds as we prepare for what social media will become next.