While counting snow crabs at sea in 2021, fisheries biologist Erin Fedewa saw that something was deeply amiss.

Fedewa, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientist, spends three or four months with a team that collects crabs from 376 stations in Alaska’s Bering Sea each year. Some of these areas always teem with crabs. Scientists count thousands. But in 2021, thousands dwindled to hundreds.

“The survey last year was a huge red flag for me,” she told Mashable.

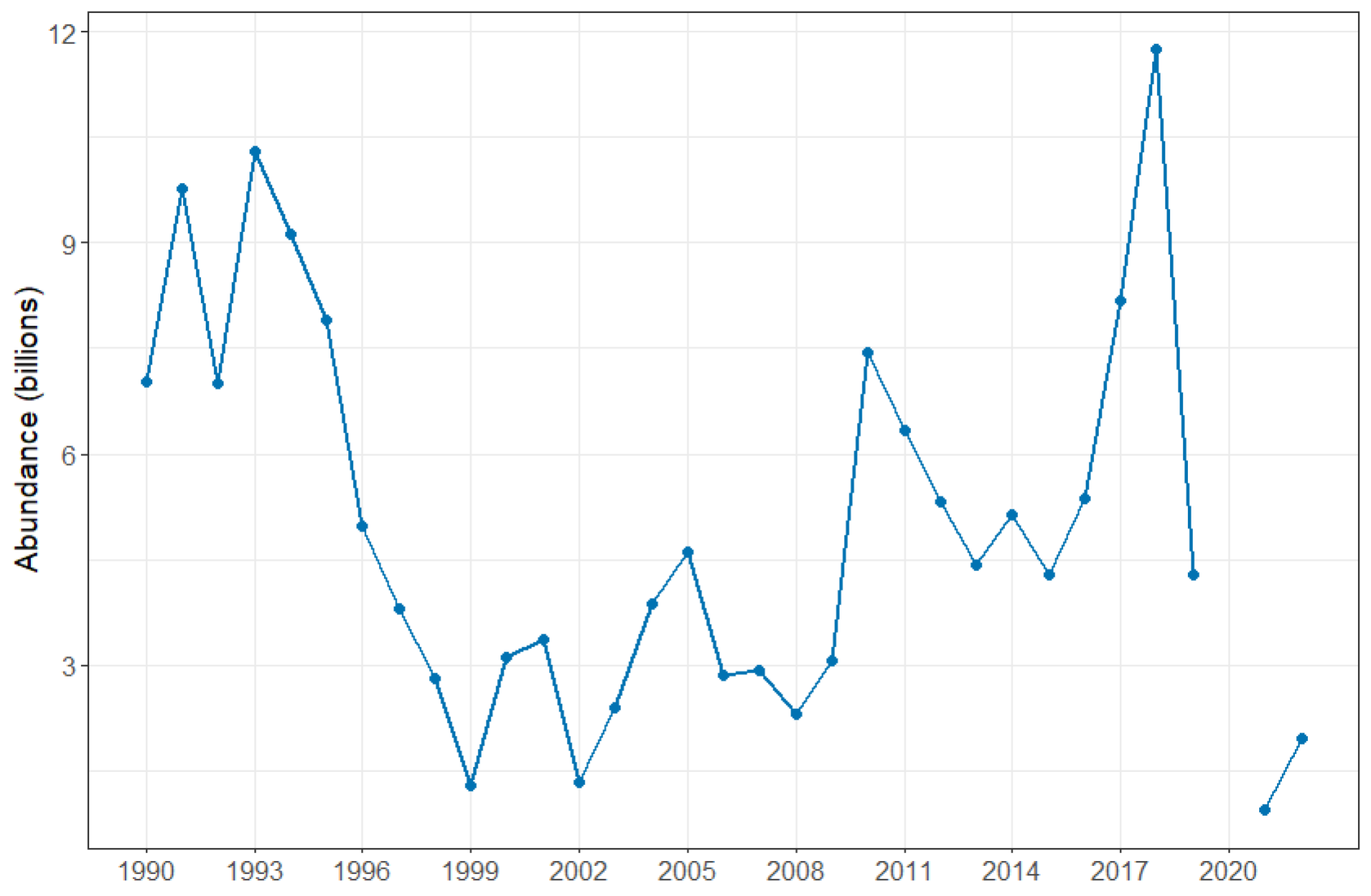

The harbingers proved right. The population of snow crabs has crashed after hitting record highs somewhat recently, in 2018. Numbers have fallen so low, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, for the first time, canceled the snow crab fishing season this year. The NOAA abundance surveys found the total snow crab population in the eastern Bering Sea dropped from an estimated 11.7 billion in 2018 down to 1.9 billion in 2022 (these surveys are a critical piece, but not the only piece, that NOAA uses to determine long-term population trends). That’s a drop of well over 80 percent.

The agency thinks a dramatic episode wiped out billions of the creatures.

“As biologists, all we can point to is some sort of large-scale mortality event,” Fedewa said.

And it’s an episode NOAA believes was ultimately stoked by exceptionally warm ocean waters in the Arctic. In other words, it could be a consequence of climate change, which can make environmental impacts significantly more extreme.

Credit: NOAA / Alaska Fisheries Science Center

How the snow crabs could have vanished

The Bering Sea, where crabs have historically flourished, is experiencing momentous upheaval.

“The Bering Sea is changing dramatically right now,” Matthew Bracken, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Irvine who researches marine ecosystems and their communities, told Mashable.

The northeast Pacific Ocean experienced a potent marine heat wave — a prolonged period of unusually warm ocean temperatures — in 2019. “That heat wave as well as earlier heat waves have been attributed to climate change,” NOAA concluded. (Overall, the Bering Sea experienced unprecedented warming between 2017 and 2019.) That’s because, similar to more frequent heat waves on land, marine heat waves are growing more frequent and intense in a warming world. Oceans are absorbing nearly unfathomable amounts of heat, and higher temperatures boost the odds of a marine heat wave occurring and persisting. Human warming of the planet is likely to blame. As researchers concluded in a recent study on marine heat waves in this region, “[temperature] forcing by elevated greenhouse gases levels has virtually certainly caused the multi-year persistent 2019–2021 marine heatwave.”

The question that looms large is how this heat stoked a massive die-off of crabs. That is under investigation, but the crucial point is that warmer temperatures can amplify mechanisms of death like increased predation, starvation, and disease. (As the graph above shows, snow crab numbers are already fickle to begin with. The species experienced a dramatic fall in 1999, which may also have been stoked by environmental changes.)

Here’s what could have happened in warmer waters:

-

Loss of sea ice = loss of crab refuge: Unsurprisingly, warmer ocean waters are a major contributor to sea ice declines. In March of 2019, for example, the lackluster Bering Sea ice almost completely disappeared — at a time when this water should have been blanketed in ice. Sea temperatures were above average, and the ice extent was the lowest in the satellite record. This loss of ice doesn’t bode well for snow crabs. When bounties of sea ice melts, the water sinks to the sea floor by summer and creates a “cold pool” (of water less than 35.6 degrees Fahrenheit, or 2 degrees Celsius) that’s too frigid for predators, like hungry cod, to roam. “That’s a refuge for baby crabs,” said Bracken. In 2019, there might have been no refuge for baby crabs.

-

Warmer waters = more disease: Warmer waters allow diseases (like bitter crab syndrome) to thrive. Disease could have spread through the snow crab population. “Whenever you have warming water temperature, that provides a venue for disease to come into the system,” Bracken explained. “More pathogens can survive.”

“The Bering Sea is changing dramatically right now.”

It’s also possible that, with significantly less sea ice, open waters could have allowed fishing vessels into previously inaccessible areas. Yet NOAA’s Fedewa notes an important issue here. The commercial fishing industry targets mature crabs — the type they can sell. Yet the agency found declines across all sizes of crab — not just the targeted crabs — which Fedewa said suggests the population decline was caused by a “bottom-up driver,” meaning something widespread impacted crab numbers at lower levels in the food chain (not from above, like extreme overfishing).

It’s within the realm of possibility that the crabs migrated and eluded the expansive surveys. But that currently seems unlikely. For example, a survey in the northern Bering Sea didn’t account for the vanished crabs. There aren’t clear answers as to where they could have crawled, though NOAA plans to investigate other seafloor areas.

Credit: NOAA Fisheries

In some “light at the end of the tunnel” news, Fedewa noted that NOAA’s intensive surveys discovered new, younger crab “recruits” in their trawling survey gear. These crabs may be five or so years away from leaving their nursery grounds, but this could mean that some of the depleted population could potentially bounce back.

NOAA and other fishery scientists will continue to research what has driven this historic collapse. In total, the estimated mass of male snow crabs that can be legally harvested fell by 44 percent in 2022 (compared to 2021). Tellingly, that’s under one-third of the 20-year average, NOAA found. It’s a giant biodiversity loss, as well as an economic loss. The Alaskan industry produced some $132 million in snow crab revenue a couple years ago.

“Science points to temperature and bigger picture climate change.”

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Top Stories newsletter today.

The evidence, however, supports the momentous changes taking place in the Arctic. It’s not surprising that snow crabs — an Arctic species — would be impacted by a warming ocean.

“Science points to temperature and bigger picture climate change,” Fedewa said.