2005 levee failures in Greater New Orleans

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Natural Disasters; Recent History

| Hurricane Katrina |

|

|

|

|

General

Impact

Relief

Analysis

Other wikis

|

|

In late August 2005 there were extensive failures of the levees and flood walls protecting New Orleans, Louisiana, and surrounding communities during Hurricane Katrina. The levee and flood wall failures resulted in the flooding of a large section of the city, causing extensive damage. Five investigations (three major and two minor) were conducted by civil engineers and other experts, in an attempt to identify the underlying reasons for the failure of the federal flood protection system designed and built by the United States Army Corps of Engineers.

Federally built levees in greater New Orleans were breached in over 50 places. The Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet Canal ("MR-GO") breached its levees in about 20 places, flooding much of New Orleans East, most of Saint Bernard Parish and the East Bank of Plaquemines Parish.

Three major breaches occurred on the Industrial Canal; one on the northeast side near the junction with MR-GO, and two on the southeast side along the Lower Ninth Ward, between Florida Avenue and Claiborne Avenue. The 17th Street Canal levee was breached on the New Orleans side near the Old Hammond Highway Bridge, and the London Avenue Canal breached in two places, near Robert E. Lee Boulevard, and near the Mirabeau Avenue Bridge. The resultant flooding put 80% of the city under water for days, in many places for weeks.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, five investigation teams studied the failure of the hurricane protection system that led to the failures, and thus most of the flooding. All five studies basically agree on the mechanisms of the levee failures, and all agree that the system designed and built by the US Army Corps of Engineers was a system in name only.

Background

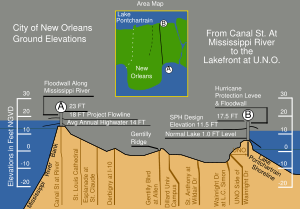

The original residents of Greater New Orleans settled on the high ground along the Mississippi River. Later developments eventually extended to nearby Lake Pontchartrian, built upon fill to bring them above the average lake level. Navigable commercial waterways extended from the lake to downtown. After 1940, the state decided to close those waterways following the completion of a new Industrial Canal for waterborne commerce. Closure of the waterways resulted in a drastic lowering of the water table by the city's drainage system, causing some areas to settle by up to 8 feet (2 m) due to the consolidation of the underlying organic soils. After 1965, the US Army Corps built a levee system around a much larger geographic footprint that included previous marshland and swamp. The average elevation of the city is between 1 and 2 feet (0.61 m) below sea level. There are no residential areas of the city that are currently more than 10 feet (3 m) below sea level.

The heavy flooding caused by Hurricane Betsy in 1965 brought concerns regarding flooding from hurricanes to the forefront. That year, congress gave the US Army Corps of Engineers sole authority for the design and construction of the flood protection in Greater New Orleans, authorizing the Pontchartrain Hurricane Protection Project, part of the Flood Control Project of 1965. The local interests' role was maintenance once the work was complete. The project was initially estimated to take 13 years, but when Katrina struck in 2005, almost 40 years later, the project was only 60–90% complete with a revised projected completion date of 2015. By comparison, President Theodore Roosevelt's construction of the Panama Canal, one of the largest and most difficult engineering projects ever undertaken, took 10 years.

On August 29, 2005, flood walls and levees catastrophically failed throughout the metro area. Many collapsed well below design thresholds (17th Street and London Canals). Others collapsed after a brief period of overtopping (Industrial Canal) caused by "scouring" or erosion of the earthen levee walls – an egregious design flaw. In April 2007, the American Society of Civil Engineers called the flooding of New Orleans "the worst engineering catastrophe in US History."

Levee and floodwall breaches

Many of the Army Corps-built levee failures were reported on Monday, August 29, 2005, at various times throughout the day. There were 28 reported levee failures in the first 24 hours and over 50 were reported in the ensuing days. A breach in the Industrial Canal, near the St. Bernard/ Orleans parish line, occurred at approximately 9:00 am CST, the day Katrina hit. Another breach in the Industrial Canal was reported a few minutes later at Tennessee Street, as well as multiple failures in the levee system, and a pump failure in the Lower Ninth Ward, near Florida Avenue.

Local fire officials reported a breach at the 17th Street Canal levee shortly after 9:00 am CST. An estimated 66% to 75% of the city was now under water.The Duncan and Bonnabel Pumping Stations were also reported to have suffered roof damage, and were non-functional.

Breaches at St. Bernard and the Lower Ninth Ward were reported at 5:00 pm CST, as well as a breach at the Haynes Blvd. Pumping Station, and another breach along the 17th Street Canal levee.

By 8:30 pm CST, all pumping stations in Jefferson and Orleans parishes were reported as non-functional.

At 10:00 pm CST, a breach of the levee on the west bank of the Industrial Canal was reported, bringing 10 feet (3.0 m) of standing water to the area.

At about midnight, a breach in the London Avenue Canal levee was reported.

The Orleans Canal about midway between the 17th Street Canal and the London Avenue Canal, engineered to the same standards, and presumably put under similar stress during the hurricane, survived intact because an incomplete section of floodwall along this canal allowed water to overtop at that point, thus creating a spill way.

Investigations

Preliminary investigations

In the 17 months following Katrina five investigations were carried out. The only federally ordered study was sponsored and managed by the Army Corps of Engineers. Two major independent studies were conducted by the University of California at Berkeley and the Louisiana State University. Two minor studies were done by FEMA and the insurance industry. All five studies basically agreed on the engineering mechanisms of failure.

The failure mechanisms engineers investigated included overtopping of levees and floodwalls by the storm surge, consequential undermining of flood wall foundations or other weakening by water of the wall foundations, and the storm surge pressures exceeding the strength of the floodwalls.

A preliminary report by the American Society of Civil Engineers in an independent investigation concluded that the flooding in the Lakeview neighbourhood was caused by the soil of the levees giving way, not by water overtopping the flood walls. Soil borings in the area of the 17th Street Canal breach showed a layer of peat starting at about 15–30 feet (9 m) below the surface, and ranging from about 5 feet (2 m) to 20 feet (6 m) thick. The peat is from the remains of the swamp on which the low areas of New Orleans (near Lake Ponchartrain) were built. The shear strength of this peat was found to be very low, and it had a high water content. According to Robert Bea, a geotechnical engineer from the University of California, Berkeley, that made the floodwall very vulnerable to the stresses of a large flood. "At 17th Street, the soil moved laterally, pushing entire wall sections with it. ... As Katrina's storm surge filled the canal, water pressure rose in the soil underneath the wall and in the peat layer. Water moved through the soil underneath the base of the wall. When the rising pressure and moving water overcame the soil's strength, it suddenly shifted, taking surrounding material – and the wall – with it."

The peat layer appears to be about 1,000 feet (300 m) wide. It is not clear if it had been properly taken into account when the levees were built. The floodwalls consist of a concrete cap on a sheet pile base driven 17.5 feet (5.3 m) deep at 17th Street Canal. A deeper piling would have anchored the flood wall in much stronger soil.

Flood wall design

Investigators focused on the 17th Street and London Avenue canals, where evidence showed they were breached even though water did not flow over their tops, indicating a design or construction flaw. Eyewitness accounts and other evidence show that levees and flood walls in other parts of the city, such as along the Industrial Canal, were topped by floodwaters first, then breached or eroded. Many New Orleans levee and flood wall failures in the wake of Hurricane Katrina occurred at weak-link junctions where different levee or wall sections joined together, according to a preliminary report released on November 2, 2005, carried out by independent investigators from the University of California, Berkeley and the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).

The original design for the steel sheet foundations for the flood walls showed a proposed depth of 10 feet (3 m), and design documents show that calculations were made with the wall base at 12.8 feet (3.9 m). According to a New Orleans engineer, the depth was apparently later increased to 17 feet (5.1 m), and this is what was built. However, a forensic engineering team from the Louisiana State University, using sonar, showed that at one point near the 17th Street Canal breach, the piling extends just 10 feet (3 m) below sea level, 7 feet (2.1 m) shallower than the Corps of Engineers had maintained. "The corps keeps saying the piles were 17 feet (5 m), but their own drawings show them to be 10", Ivor van Heerden said. "This is the first time anyone has been able to get a firm fix on what's really down there. And, so far, it's just 10 feet (3 m). Not nearly deep enough." Other reports confirmed that construction on the London Avenue and Industrial Canal levees was similarly below the stated standard. They also found that homeowners along the 17th Street Canal, near the site of the breach, had been reporting their yards flooding from persistent seepage from the canal for a year prior to Hurricane Katrina. Other studies showed the levee floodwalls on the 17th Street Canal were, "destined to fail,", from bad Army Corps of Engineers design, saying in part, "that miscalculation was so obvious and fundamental," investigators said, they, "could not fathom how the design team of engineers from the corps, local firm Eustis Engineering and the national firm Modjeski and Masters could have missed what is being termed the costliest engineering mistake in American history."

Dr. Robert Bea, chair of an independent levee investigation team, has said that the New Orleans-based design firm Modjeski and Masters could have followed correct procedures in calculating safety factors for the flood walls. He added, however, that design procedures of the Army Corps may not account for changes in soil strength caused by the changes in water flow and pressure during a hurricane flood. Dr. Bea has also questioned the size of the design safety margins. He said the corps applied a 30% margin over the maximum design load. A doubling of strength would be a more typical margin for highway bridges, dams, off-shore oil platforms and other public structures. There were also indications that substandard concrete may have been used at the 17th Street Canal.

The two sets of November tests conducted by the Army Corps and LSU researchers used non-invasive seismic methods. Both studies understated the length of the piles by about seven feet. By December, seven of the actual piles had been pulled from the ground and measured. The Engineering News Record reported on December 16 that they ranged from 23' 31/8" to 23' 77/16" long, well within the original design specifications, contradicting the early report of short pilings. The suitability of the original design specifications, however, continues to be contested.

In August 2007, the corps released an analysis revealing that their floodwalls were so poorly designed that the maximum safe load is only 7 feet (2.1 m) of water, which is half the original 14-foot (4.3 m) design.

Overtopping of levees in the Eastern New Orleans

According to Professor Raymond Seed of the University of California, Berkeley, a surge of water estimated at 24 feet (7 m), about 10 feet (3 m) higher than the height of the levees along the city's eastern flank, swept into New Orleans from the Gulf of Mexico, causing most of the flooding in the city. He said that storm surge from Lake Borgne travelling up the Intracoastal Waterway caused the breaches on the Industrial Canal.

Aerial evaluation revealed damage to approximately 90% of some levee systems in the east which should have protected St. Bernard Parish.

Levee maintenance

Maintenance and inspection are the responsibility of local levee boards, but the levee failures were not due to maintenance, but rather to design flaws that routine maintenance would not have detected.

National Academy of Sciences Investigation

On October 19, 2005, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld announced that an independent panel of experts, under the direction of the National Academy of Sciences, would convene to evaluate the performance of the New Orleans levee system, and issue a final report in eight months. The panel would study the results provided by the two existing teams of experts that had already examined the levee failures.

Senate Committee hearings

Preliminary investigations and evidence were presented before the U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs on November 2, 2005, and generally confirmed the findings of the preliminary investigations.

On November 9, 2005, The Government Accountability Office testified before the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works. The report cited the Flood Control Act of 1965, which authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to design and construct a flood protection system to protect south Louisiana from the strongest storms characteristic of the region.

In his written evidence to the committee, Ivor van Heerden, from Louisiana State University, concluded, "Most of the flooding of New Orleans was due to man's follies. Society owes those who lost their lives, and the approximately 100,000 families who lost all, an apology and needs to step up to the plate and rebuild their homes, and compensate for their lost means of employment. New Orleans is one of our nations jeweled cities. Not to have given the residents the security of proper levees is inexcusable."

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers admits fault

On April 5, 2006, months after independent investigators had demonstrated that the levee failures were not due to natural forces beyond intended design strength, Lt. Gen. Carl Strock testified before the U. S. Senate Subcommittee on Energy and Water that, "We have now concluded we had problems with the design of the structure." He also testified that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers did not know of this mechanism of failure prior to August 29, 2005. The claim of ignorance is refuted, however, by the National Science Foundation investigators hired by the Army Corps of Engineers, who point to a 1986 study by the corps itself that such separations were possible in the I-wall design.

Nearly two months later, on June 1, 2006, the USACE finally and unequivocally admitted responsibility for the events in New Orleans with the release of the completed report. The final draft of the IPET report states the destructive forces of Katrina were "aided by incomplete protection, lower than authorized structures, and levee sections with erodible materials."