Canute the Great

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: British History 1500 and before (including Roman Britain); Monarchs of Great Britain

| Canute the Great | |

| King of England, Denmark, Norway, as well as some of Sweden | |

|

|

| Reign | England: 1016 - November 12, 1035 Denmark: 1018 - November 12, 1035 Norway: 1028 - 1035 |

|---|---|

| Born | ca. 995 |

| Birthplace | Denmark |

| Died | 1035 |

| Place of death | England ( Shaftesbury, Dorset) |

| Buried | Old Minster, Winchester. Bones now in Winchester Cathedral |

| Predecessor | Edmund Ironside (England) Harald II (Denmark) Olaf Haraldsson (Norway} |

| Successor | Harold Harefoot (England) Harthacanute (Denmark) Magnus Olafsson (Norway) |

| Consort | Aelgifu of Northampton Emma of Normandy |

| Father | Sweyn Forkbeard |

| Mother | Saum-Aesa, or Gunnhilda |

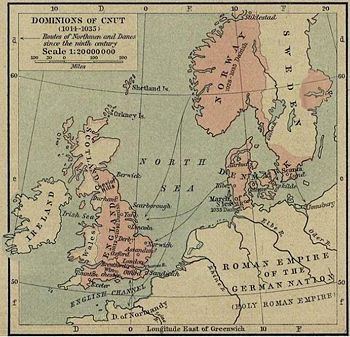

Canute I, or Canute the Great, also known in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles as Cnut ( Old Norse: Knútr inn ríki, Norwegian: Knut den mektige, Swedish: Knut den store, English: also Knut, Danish: Knud den Store) (ca. 995 – November 12, 1035) was a Viking king of England, Denmark, Norway, of some of Sweden (such as the Sigtuna Swedes), as well as overlord of Pomerania, and the Mark of Schleswig. He was in treaty with the Holy Roman Emperors, the German kings, Henry II and Conrad II, the vassals of the pontificate, and, in relations with the papacy. His rule was over a northern empire which saw Danish sovereignty at its height.

Description of Cnut

Here is a description of Cnut's physical appearance. It is an excerpt from the Knytlinga Saga of the 13th century:

- Knutr was exceptionally tall and strong, and the handsomest of men, all exept for his nose, which was thin, high set, and rather hooked. He had a fair complexion none the less, and a fine, thick head of hair. His eyes were better than those of other men, both the more handsome and the keener of their sight. (Dual, and , sources)

Birth and Kingship

Canute was a son of the Danish king Swegen Forkbeard and his queen, Saum-Aesa, lent her Scandinavian name Gunnhilda by the Danes, whom, in accord with the Monk of St Omer's, Encomium Emmae, and, Thietmar of Merseburg's contemporary Chronicon, was a Slavic princess, daughter to the first Duke of Poland. Cnut, as an heir to a line of Scandinavian rulers central to unification of Denmark, with its origins in the obscure Harthacnut, founder of the royal house and father to Gorm the Old, its official progenitor, was born for a solidly military life. It is verily written, in the Flatayarbok, a thirteenth century source, with some certainty, that as a youth Cnut was brought up in the company of a chieftain known as Thorkel the Tall, brother to Sigurd, Jarl of mythical Jomsborg, and the legendary Joms, at their Viking stronghold, now thought to be a Slavic fortress on the Island of Wollin.

Canute's date of birth is an unknown, as covergage of his life, such as contemporary works known as the Encomium Emmae and the Chronicon, give it no mention. Still, in the skald Ottar the Black's Knutsdrapa there is a statement that Cnut began his career unusually young, while it mentions an attack on Norwich also, which might be one his father lead, in 1004. If it is the case that Cnut fought in this battle, his birthdate may be near 990, or even 980. If not, and the skald's poetic verse envisages a later assault, it may even suggest a date nearer 1000 to be the one of his birth, with his war years begun in his father's English conquest. His age at the time of his death, and the moments of his life as king, are never otherwise of any especial mention. The encomium of Emma only states that Cnut was rather youthful, while Thietmar seems to think it of no importance, which is information of sorts.

Concisely, hardly anything is known for sure of Cnut's life... that is, until the year he was with a Scandinavian force under his father, the Danish king Swegen Forkbeard, for his invasion of England, in August, 1013. It was the crux of many Viking raids over past decades, with centuries of their territorial involvement in England, particulary with the peoples of Denmark in the Danelaw, and the English kingdom fell easily under the pressure of a conquest.

Over winter, Cnut's father was in the process of consolidation for the Danish claim of the Anglo-Saxons, while he was left the charge of the army, and base of the fleet, at Gainsborough, in Lincolnshire, which was probably down a considerable number, likely to have been sent home for winter once the payments for their services were made. Any support for the conquest was at the cost of silver and gold. Fortuitously, upon the sudden death of Swegen, in February, 1014, Canute was held by the Vikings to be their commander, a warlord, and King of England.

At the Witan, England's nobility refused to accept Cnut's claim, and restored the Englishman and former king, Ethelred the Unready, in exile with his in-laws in Normandy. It was an act which meant the English kingdom, possibly with Norman knights in its forces, had made Canute abandon his kingship, and sail back to Denmark with the remnants of the invasion, with it held in contempt of the rights of conquest. On the beaches of Sandwich, the Danes mutilated their hostages, taken from the English as pledges of allegiance given to Forkbeard.

On the death of Sweyn Forkbeard, the King of Denmark was Cnut’s older brother Harald. Cnut supposedly made the suggestion of joint rulership, although this found no ground with Harald. In due kind, Harald was to offer Cnut the command of the Danes for their second conquest of England, on the condition he laid off on his claim to the Danish kingdom. Canute, with acceptance of this proposition, kept silent, ready for the moment to present itself when he could settle his scores with the nobles, and sit once again as ruler over the Kingdom of England.

Conquest of England

Canute's fleet set off for England, in summer, 1015, with a Danish army of 10,000 men, along with support from the allies of Denmark. Boleslaw the Brave, the Duke of Poland, and Cnut's uncle, lent some token Slav troops, likely to have been a pledge made while Cnut and his brother Harald went to fetch their mother home, in winter, 1014, since their father sent her away from the Danish court. Olof Skötkonung, King of Sweden, was a strong ally, as son of Sigrid the Haughty, by her first husband, Sweden's progenal king Eric the Victorious, and, by her second husband, Swegen Forkbeard, the step-brother of Cnut. Eiríkr Hákonarson, Cnut's brother-in-law, as well as, Trondejarl, the Earl of Lade, and ruler of Norway, under Swegen, and the sons of Forkbeard too, as within the liege and lord alliance, was left with the campaign reserves in Denmark. He was to join Canute once the invasion began, while there were possibly still men to gather, with their probable dispersal, in winter, 1013.

Thorkell the High, who fought with Ethelred, in 1013, after his alliance to the English, in 1012, as a Joms chief, also was with Cnut, along with his Joms. An explanation for this particular Jomsviking's, as well as Jomsborg's, shift of allegiance, may be found in a stanza of the Jomsvikingsaga with a statement that two attacks were launched against the Viking mercenaries while they were in England, maybe at Ethelred's command. And to add insult to injury, amongst their dead soldiers was a chieftain of the Jomvikings known as Henninge, who was also a brother to Thorkell the Tall. Likewise, if it is true that Cnut's childhood mentor was indeed this man, here may be the reason for Cnut's acceptance of the allegiance after an opposition against his father's previous expedition. Cnut and the Jomsviking, ultimately in the service of Jomsborg, were in a difficult relationship, which was apparent until , in 1023, Thurkil the High eventually falls out of historical note.

Eadric Streona, a nobleman risen far to be the wealthy Earl of Mercia under his king, Ethelred, also thought it prudent to join in Cnut's invasion, with forty ships, though these were probably of the Danelaw anyway. England's king was clearly at a wits end, and the distresses which were a fact of his reign, as a man risen to sovereignty through assassination, were too much for many to put up with. In spite of his faults, the Mercian Earl was a strong ally to be had, pivotal to any successes which the English might hope to make, and he probably knew it.

With these, and his brother Harald's aid, Cnut was at the head of an epic array of Vikings, from all over Scandinavia. Altogether, the invasion force, to be in fourteen months of often close and grisly warfare under Cnut, with most of the battles against Ethelred's son, Edmund Ironside, was more formidable than any seen since the Anglo-Saxon's black days under Alfred the Great. The same royal house of Wessex that stood against the tide of Vikings then, stood against it still, although now the might of Cnut was to prove too great for the English.

Here is a passage out of the Encomium Emmae which paints a good picture of the scence which was to confront the English as Cnut and his Vikings, whom, as the author writes, had 200 ships, made landfall:

- There were so many kinds of shields, that you could have believed that troops of all nations were present... Gold shone on the prows (of their ships), silver also flashed... who could look upon the lions of the foe, terrible with the brightness of gold, who upon the men of metal, who upon the bulls on the ships threatening death, their horns shining with gold, (who), without feeling any fear for the king of such a force. Moreover, in the whole force there could be found no serf, no freedman, none of ignoble birth, none weak with old age. All were nobles, all vigourous with the strength of complete manhood, fit for all manner of battle, and so swift of foot that they despised the speed of cavalry. (Dual, and , sources).

In September, 1015, Cnut was seen off shore of Sandwich again, and the fleet went around on the coast about Kent until it came upon the mouth of the Frome, where it put to land and began the occupation of Wessex. Cnut had his army gather supplies and made a base of the English heartland, with his fleet at his back.

Until mid-winter the Vikings stood their ground, with Ethelred held up in London. Cnut's invaders then went across the Thames, with no pause in bleak weather, through the Mercian lands, northwards, to confront Uhtred, the Earl of Northumbria, and Edmund Ironside, commander of England's army. Cnut found these lands without their main garrisons, as Uhtred was away with Ironside in Mercia to countermand the properties of Eadric Streona. Northumbria fell, while at Uhtred's return to sue for peace, for breaking oaths pledged to Sweyn Forkbeard two years earlier, Canute was to execute its Earl, which left Ironside alone. Cnut brought over Eiríkr Hákonarson and strategically put the Norwegian in control of Northumbria, while he had his army made stronger with the reserves.

In April, 1016, Cnut made his way south through the western shires to gather as much support from the English as possible, already confident in the eastern Danelaw, and the Scandinavian fleet came up the Thames to lay London under siege. Edmund Ironside was effectively swept before this onslaught, which left London as his last resort, while it was also the refuge of his father. Ethelred's death on April the 23rd meant he was England's king, after his official election by the nobles, and the townsfolk. Over the next couple of months the Vikings were to surround the city and dug a canal through which to pull their ships to the western side of London, from the east, and cut off the supply lines of the river. Encirclement was complete by the construction of dikes on the city's north and south sides. Attacks on the walls too were frequent, although London could not be beaten unless it was to surrender the keys for its gates.

In the summer Ethelred's heir broke out of London to raise an army in the Wessex countryside, and the Vikings broke off a portion of the siege in pursuit, under Canute's leadership. Edmund Ironside's forces were now caught on the last reaches of their kingdom, practically in a corner with the sea at their backs. Like the resistance of Alfred the Great against the Vikings in his day, the English were to rally at Penselwood, with a hill in the Selwood as the likely location of their stand. The battle which was fought did not leave any clear victor while another fought at Sherston in Wiltshire was again over with no side in clear advantage. Cnut's invasion force purportedly brought each of the battles to their end with retreats, although it is likely it was simply darkness which meant the blood shed could not continue.

Edmund Ironside did eventually end the siege of London, with the Scandinavians in disarray, although Cnut was able to get his forces back together in Wessex and the attack was brought to bear on the city again. London was still not beaten though, and the invaders had to make their way north into Mercia and get more supplies. At which point Eadric Streona thought it wise to ally himself with the English again. Cnut's men were subsequently put under attack in Kent, and the army of Edmund Ironside sent the Vikings back, on to the Isle of Sheppy. These men went north too, and the invasion force was all together again in Essex with Cnut at its head, along with Thorkell the High. Here, in October, at Assandun, on the hill of ash trees, the two armies came together for one last assault. A decisive victory in the Battle of Ashingdon, which saw Eadric Streona again betray his countrymen with his ungainly retreat amidst the carnage, along with his men, meant the Viking army won the domination of England.

Edmund Ironside, probably suffering and fatally wounded, was caught in retreat half way across the country, near Wales and the Forest of Dean, where there was likely to have been a final struggle made in an attempt by the English to protect their king. Cnut was ultimately able to force them into peace talks, on the terms which he set, or none.

Cnut and Ironside met on an island in the Severn, which left King Edmund only to accept defeat and sign a treaty with Canute in which all of England except for Wessex would be controlled by Canute, and when one of the kings should die, the other king would be the one and only king of England; his sons being the heir to the throne. It was a move of astute political sense, as well as mercy, on the part of the Viking leader. After Edmund's death, possibly murder, by the hand of the traitor Eadric Streona's men, probably by the afflictions of war, on November the 30th, in 1016, Canute ruled the whole kingdom. Canute was recognised by the nobility as the sole king in January 1017, yet his coronation was at Christmas.

It was at the coronation that Cnut saw to the decapitation of the untrustworthy Eadric Streona, and the head was put on a pole for all to see. This execution was by the hand of his Earl of Northumbria, Erikr. If it was in reaction to the dishonour of murder against the former king, or simply disloyalty, that lead Cnut to this man's execution, it is unsure. He was now King of England though, and the throne could be kept only under a ruler who was seen by the people as just, even ruthlessly, as well as liberal to their cause. Trechery was the main threat which put Cnut's life in peril. Him as the Viking whom was to be one of England's most successful kings, with a wide unity across Scandinavia and the North Atlantic.

In July 1017, to associate his line with the overthrown English dynasty, as well as to protect himself against his aggressors in Normandy, where Ethelred's sons Edward the Confessor and Alfred Atheling were in exile, Emma of Normandy, daughter of Richard the Fearless, Duke of Normandy, was married to Canute. She was Ethelred's widow, and held the keys to a secure English court in more ways than one. Cnut duly proclaimed their son Harthacanute as his heir, while his first sons with Aelgifu of Northampton were left on the sidelines. He sent Harthacnut to Denmark while he was still a boy, and the heir to the throne was brought up, like he was himself, as a soldier of the Vikings.

King of England

Cnut's first act in the country, in 1017, was to officially divide it into the four great earldoms of Wessex, his personal fief, Mercia, to be given to Leofric after its previous Earl's death, Northumbria, for Eric, and East Anglia, for Thorkel. This was to be the basis for the system of feudal baronnies which were to underlie English sovereignty for centuries, while the very last Danegeld ever paid, a sum of £82,500, went to Canute, in 1018, a significant proportion of which was levied from the citizenry of London alone. He felt secure enough to send the invasion fleet back to Denmark with £72,000 that same year.

Cnut's brother Harald was maybe in England for his coronation, if not for the conquest, while it may be he went back to Denmark, as king, at some point thereafter. It is though, only sure that his name was to enter a confraternity with Christ Church, Canterbury, in 1018. This though, is not conclusive, as the entry may have been made for him, by the hand of Cnut himself even, which means it is unsure if he was dead or alive at the time. Nevertheless, it is usually thought that Harald's life was at its end, in 1018.

Cnut mentions the suppression of troubles in his 1019 Letter, written as the King of England, and Denmark, which can be seen, with some plausibility, in connection to the death of Harald. If it was a rebellion, which Cnut his Letter says he put down to ensure that Denmark was free to assist England, then his brother's hold on the throne was tenuous, although there is no reason to think there was not a smooth enough succession, by the standards of the time. Harald's name in the Caterbury codex may have been Cnut's ritual to make his vengence for a murder good with the Church.

As King of England, Canute combined English and Danish institutions and personnel. His mutilation of the hostages taken by his father in pledge of English loyalty is remembered above all as being uncharacteristic of his rule.

Canute reinstated the laws passed under King Edgar. However, he reformed the existing laws and initiated a new series of laws and proclamations. Two significant ones were On Heriots and Reliefs, and Inheritance in Case of Intestacy. He strengthened the coinage system, and initiated a series of new coins which would be of equal weight as those being used in Denmark and other parts of Scandinavia. This greatly improved the trade of England, whose economy was in turmoil following years of social disorder.

Canute is generally regarded as a wise and successful king of England, although this view may in part be attributable to his good treatment of the church, which controlled the history writers of the day. However, he brought England more than two decades of peace and prosperity. The medieval church loved order and believed in supporting good and efficient government, whenever the circumstances allowed it. Thus we see him described even today as a religious man, despite the fact that he lived openly in what was effectively a bigamous relationship, and despite his responsibility for many political murders.

King of Denmark

Upon Sweyn Forkbeard's death, Cnut's brother Harald was King of Denmark. Cnut went to Harald to ask for his assistance in the conquest of England, and the division of the Danish kingdom. His plea for division of kingship was denied, though, and the Danish kingdom remained wholly in the hands of his brother, although, Harald lent to Cnut the command of the Danes in any attempt he had a mind to make on the English throne.

It is possible Harald was at the siege of London, although as the King of Denmark, with Cnut in control of the invasion. He was to enter the faternity of Christ Church, Canterbury, after which he sailed back to Denmark, in 1018, with the fleet of his Danes.

In 1018 Harold II died and the Kingdom of Denmark was Canute's. His sailing back home in 1019 to over-winter was to affirm his succession as the King of Denmark. With a Letter in which he states intentions to avert troubles to be done against England, it seems Danes were set against him, and the attack on the Wends was possibly part of his suppression of dissent. In the spring of 1020 he was back in England, his hold on Denmark assumedly stable. Ulf Jarl, his brother-in-law, was his appointee as the Earl of Denmark.

When the Swedish king Anund Jakob and the Norwegian king Saint Olaf took advantage of Canute's absence and attacked Denmark, Ulf gave the freemen cause to elect Harthacanute king, discontent with Canute, in England. This was a ruse of Ulf's, since the role the earl had as the caretaker of Harthacanute subsequently made him the holder of Denmark's kingly reigns. When Canute learnt of this, in 1026, he returned to Denmark and, with Ulf Jarl's help, he defeated the fleet of Swedes and Norwegians at the Battle of Helgeå. This service, did not, though, allow Ulf the forgiveness of Canute for his coup. At a banquet in Roskilde, the two brothers-in-law were playing chess and started a row with each other. The next day, the Christmas of 1026, one of Cnut's housecarls, with his blessing, killed Ulf Jarl, in the Church of Trinity. Contradictory evidences of Ulf's death gather doubt to this though.

King of Norway and the Swedes of Sigtuna

Earl Eiríkr Hákonarson was ruler of Norway under Cnut's father, Forkbeard, and the invasion of England in 1015-16 was with the assistance of Norwegians under Erik. Cnut showed his appreciation, awarding Eiríkr the office to the Earldom of Northumbria. Sveinn, Eiríkr's brother, was left in control of Norway, although he was beaten at the Battle of Nesjar, in 1015 or 1016, and the son of Eiríkr, Håkon, fled to his father. Of the line of Fairhair, Olaf Haraldsson was then King of Norway, and the Danes lost their control.

Thorkell the Tall, said to be a chieftan of the Jomsvikings, was a former associate of the now King Olav of Norway, and the difficulties Cnut found, in Denmark, as well as with Thurkel, were maybe to do with Norwegian pressure on the Danish lands. Jomsborg, the legendary stronghold of the Jomvikings, was possibly on the south coast of the Baltic Sea, which, if the Joms were on the side of Olaf, may account for the attack on the Wends of Pomerania, as Jomsbourg was, maybe, at the heart of this territory. King Olof Skötkonung of Sweden was an ally of Cnut's, as well as his step-brother. His death, in 1022, though, and the succession of his son, Anund Jacob, meant the Danish domains were now under threat of the Swedes too.

In a battle known as the Holy River, with an alliance between the kings Olaf Haraldsson and Anund Olafsson, the Swedes and Norwegians were attacked in the mouth of a river Helgea by the navy of Cnut. 1026 is the likely date, and the apparent victory left Cnut in control of Scandinavia, confident enough with his dominance to make the journey to Rome, and the coronation of Conrad II as Holy Roman Emperor, on March 26, 1027. He considered himself ruler of Sweden (victory over Sweden suggests Helgea to be a river near Sigtuna, while some Swedes appeared to have been made renegades, with a hold on the parts of Sweden too remote to threaten Cnut, which left the former king alive) and Norway (it's former king still alive), with his Letter, in 1027. He also stated his intention to return to Denmark, to secure peace.

In 1028, Canute set off with a fleet of fifty ships from Denmark, to Norway, and the city of Trondheim. Olaf Haraldsson stood down, unable to put up any fight, as his nobles sided against him, swayed with offers of gold, and the tendency of their lord to falay their wives for sorcery. Cnut was crowned king, his office, now, “King of all England and Denmark, and the Norwegians, and some of the Swedes”. He trusted the Earldom of Lade to the former line of earls, in Håkon Eiriksson, with Earl Eiríkr Hákonarson probably dead at this date, although was to drown in the ship which bore him to his charge. St Olaf returned, with Swedes in his army, to be defeated at the hands of his own people, at the Battle of Stiklestad, in 1030.

Cnut's attempt to rule Norway through Aelgifu of Northampton and his second son by her, Sweyn, was to be put to an end, with his death, in rebellion, and the restoration of the former Norwegian dynasty under Olaf's son Magnus the Good.

Other continental domains

On the death of his father, Henry II, in 1024, with an eye to end previously tense relations, the Holy Roman Emperor, Conrad II, was friendly with Canute. Conrad's son, Henry, to be, Henry III, was, at his request, bound in a betrothal with Canute's daughter, Chunihildis (Gunhild). Cnut's southern ally felt it appropriate to cede to him princedoms on the German border with Denmark, in the Mark of Schleswig.

Pomerania was probably already a fief of Canute's, since Boleslaus I of Poland sent his army to help Canute conquer England. Many legends also relate the rulers of the Danish kingdom to the mythical Jomsvikings, whose stronghold, Jomsborg, is thought to have been made at the delta of the Oder river, on the Island of Wolin.

Relations with the Church

It is hard to conclude if Canute’s devotion to the Church came out of deep religious devotion or merely as a means to consolidate and increase his political power. Even though Canute was accepted as a Christian monarch after the conquest, the army he led to England was largely heathen, so he had to accept the tolerance of the pagan religion. His early actions made him uneasy with the Church, such as the execution of the powerful earls in England in 1016, as well as his open relationship with a concubine Aelgifu of Northampton, who he treated as his northern queen.

However, his treatment of the Church could not have been more sincere. Canute not only repaired all the churches and monasteries that were looted by his army, but he also constructed new ones. He became a patron of the monastic reform, which was popular among the ecclesiastical and secular population. The most generous contribution he is remembered for is the impressive gifts and relics that he bestowed upon the English Church.

Canute’s pilgrimage to Rome in 1027 was another sign of his dedicated devotion to the Christian faith. It is still debated whether he went to repent his sins, or to attend Emperor Conrad II’s coronation in order to improve relations between the two powers. While in Rome, Canute obtained the agreement from the Pope to reduce the fees paid by the English archbishops to receive their pallium. He also arranged with other Christian leaders that the English pilgrims should pay reduced or no toll tax on their way, and that they would be safeguarded on their way to Rome.

Succession

Canute died in 1035, at Shaftesbury in Dorset, and was buried in the Old Minster in Winchester. When the current Winchester Cathedral was built on the site of the Saxon minster, Canute's bones were moved to a mortuary chest. During the English Civil War of the 17th century, the bones were spilled out and are now scattered in various chests along with those of other English kings such as Egbert of Wessex and William Rufus. On his death, Canute was succeeded in Denmark by Harthacanute, reigning as Canute III. Harold took power in England, however, ruling until his death (1040), whereupon the two crowns were again briefly reunited under Harthacanute.

Marriages and issue

- 1 - Aelgifu of Northampton

- Sweyn Knutsson reigned Norway ca. 1030-35 with his mother

- Harold Harefoot who later became Harold I of England

- 2 - Emma of Normandy

- Harthacanute, reigned as Canute III

- Gunhilda of Denmark, possibly buried at Bosham, married to Henry III, son of Conrad II, both these, Holy Roman Emperors.

Family-tree

| Harald Bluetooth |

|

|

Mieszko |

|

Dubrawka |

|

William |

|

Sprota | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Sweyn |

|

Gunhilda |

|

|

|

Gunnora |

|

Richard | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aelgifu of Northampton |

|

Canute |

|

Emma of Normandy |

|

Ethelred the Unready |

|

Aelflaed, 1st wife |

|

|

|

Richard |

|

Judith | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sweyn Knutsson |

|

Harold Harefoot |

|

|

Gunhilda of Denmark |

|

|

Alfred Aetheling |

|

Edmund II |

|

Ealdgyth |

|

Robert |

|

Herleva | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gytha Thorkelsdóttir+ |

|

Godwin, Earl of Wessex |

|

Harthacanute |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Edward |

|

Agatha |

|

William |

|

Matilda | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sweyn |

|

Harold II |

|

Tostig |

|

|

Edith |

|

Edward the Confessor |

|

Edgar Ætheling |

|

|

|

|

|

Cristina |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gyrth, Gunnhilda, Aelfgifu, Leofwine & Wulfnoth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malcolm |

|

Margaret |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other children |

|

Edith of Scotland |

|

Henry | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

+Said to have been a great-granddaughter of Canute's grandfather Harald Bluetooth, but this was probably a fiction intended to give her a royal bloodline.

Popular Culture

Canute is perhaps best remembered for the legend of how he commanded the waves to go back. According to the legend, he grew tired of flattery from his courtiers. When one such flatterer gushed that the king could even command the obedience of the sea, Canute proved him wrong by practical demonstration (at Southampton or Bosham; other sources say these events took place near his palace at Westminster), to demonstrate that even a king's powers have limits. Having demonstrably failed to command the waves he removed his crown, refusing to wear it again, claiming that there was no true king except Jesus.

Sanding the streets of Knutsford is generally thought to have made its appearance in Cnut's reign. There is a peculiar custom of "sanding the streets" in the small British town of Knutsford. This custom is to decorate the streets with coloured sands in patterns and pictures, that continues to this day. Specifically it is held now to celebrate May Day.

Tradition has it that King Canute, while he forded the River Lily, threw sand from his shoes into the path of a wedding party. The custom can be traced to the late 1600s. Queen Victoria, in her journal of 1832 recorded: "we arrived at Knutsford, where we were most civilly received, the streets being sanded in shapes, which is peculiar to this town".