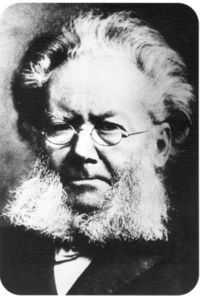

Henrik Ibsen

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Theatre; Writers and critics

| Henrik Ibsen | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Henrik Johan Ibsen March 20, 1828 Skien, Norway |

| Died | May 23, 1906 (aged 78) Kristiania (Oslo), Norway |

| Pen name | Brynjolf Bjarme (early works) |

| Occupation | Playwright, poet, theatre director |

| Nationality | Norwegian |

| Genres | Social Realism |

| Notable work(s) | Peer Gynt (1867) A Doll's House (1879) Ghosts (1881) The Wild Duck (1884) Hedda Gabler (1890) |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Henrik Johan Ibsen (pronounced [ˈhɛnɾɪk ˈɪpsən]; March 20, 1828– May 23, 1906) was a major Norwegian playwright of realistic drama. He is often referred to as the "father of modern drama." Ibsen is held to be, alongside Knut Hamsun, the greatest of Norwegian authors and one of the most important playwrights of all time, celebrated as a national symbol by Norwegians.

His plays were considered scandalous to many of his era, when Victorian values of family life and propriety largely held sway in Europe and any challenge to them was considered immoral and outrageous. Ibsen's work examined the realities that lay behind many facades, possessing a revelatory nature that was disquieting to many contemporaries.

Ibsen largely founded the modern stage by introducing a critical eye and free inquiry into the conditions of life and issues of morality. Victorian-era plays were expected to be moral dramas with noble protagonists pitted against darker forces; every drama was expected to result in a morally appropriate conclusion, meaning that goodness was to bring happiness, and immorality pain. Ibsen challenged this notion and the beliefs of his times and shattered the illusions of his audiences.

Family and youth

Henrik Ibsen was born to Knud Ibsen and Marichen Altenburg, a relatively well-to-do merchant family, in the small port town of Skien, Norway, which was primarily noted for shipping timber. He was a descendant of some of the oldest and most distinguished families of Norway, including the Paus family. Ibsen later pointed out his distinguished ancestors and relatives in a letter to Georg Brandes. Shortly after his birth his family's fortunes took a significant turn for the worse. His mother turned to religion for solace, and his father began suffering from severe depression. The characters in his plays often mirror his parents, and his themes often deal with issues of financial difficulty as well as moral conflicts stemming from dark private secrets hidden from society. It is not surprising that there is only one known photograph of Ibsen in which he is smiling.

At fifteen, Ibsen left home. He moved to the small town of Grimstad to become an apprentice pharmacist and began writing plays. In 1846, he fathered an illegitimate child with a servant maid whom he rejected. While Ibsen did pay some child support money for fourteen years, he never met his illegitimate son, who ended up as a poor blacksmith. Ibsen went to Christiania (later renamed Oslo) intending to attend the university. He soon cast off the idea (his earlier attempts at entering university were blocked as he did not pass all his entrance exams), preferring to commit himself to writing. His first play, the tragedy Catilina (1850), was published under the pseudonym Brynjolf Bjarme, when he was only 22, but it was not performed. His first play to be staged, The Burial Mound (1850), received little attention. Still, Ibsen was determined to be a playwright, although he was not to write again for some years.

Life and writings

He spent the next several years employed at the Norwegian Theatre in Bergen, where he was involved in the production of more than 145 plays as a writer, director, and producer. During this period he did not publish any new plays of his own. Despite Ibsen's failure to achieve success as a playwright, he gained a great deal of practical experience at the Norwegian Theatre, experience that was to prove valuable when he continued writing.

Ibsen returned to Kristiania in 1858 to become the creative director of Kristiania's National Theatre. He married Suzannah Thoresen the same year and she gave birth to their only child, Sigurd. The couple lived in very poor financial circumstances and Ibsen became very disenchanted with life in Norway. In 1864 he left Christiania and went to Sorrento in Italy in self-imposed exile. He was not to return to his native land for the next 27 years, and when he returned it was to be as a noted playwright, however controversial.

His next play, Brand (1865), was to bring him the critical acclaim he sought, along with a measure of financial success, as was his next play, Peer Gynt (1867), to which Edvard Grieg famously composed the incidental music. Although Ibsen read excerpts of the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and traces of the latter's influence are evident in Brand, it was not until after Brand that Ibsen came to take Kierkegaard seriously. Initially annoyed with his friend Georg Brandes for comparing Brand to Kierkegaard, Ibsen nevertheless read Either/Or and Fear and Trembling. Subsequently, Ibsen's next play Peer Gynt was consciously informed by Kierkegaard.

With success, Ibsen became more confident and began to introduce more and more of his own beliefs and judgments into the drama, exploring what he termed the "drama of ideas." His next series of plays are often considered his Golden Age, when he entered the height of his power and influence, becoming the centre of dramatic controversy across Europe.

Ibsen moved from Italy to Dresden, Germany in 1868. Here he spent years writing the play he himself regarded as his main work, Emperor and Galilean (1873), dramatizing the life and times of the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate. Although Ibsen himself always looked back on this play as the cornerstone of his entire works, very few shared his opinion, and his next works would be much more acclaimed. Ibsen moved to Munich in 1875 and published A Doll's House in 1879. The play is a scathing criticism of the blind acceptance of traditional roles of men and women in Victorian marriage.

Ibsen followed A Doll's House with Ghosts (1881), another scathing commentary on Victorian morality, in which a widow reveals to her pastor that she had hidden the evils of her marriage for its duration. The pastor had advised her to marry her then fiancé despite his philandering, and she did so in the belief that her love would reform him. But she was not to receive the result she was promised. Her husband's philandering continued right up until his death, and the result is that her son is syphilitic. Even the mention of venereal disease was scandalous, but to show that even a person who followed society's ideals of morality had no protection against it, that was beyond scandalous. Hers was not the noble life which Victorians believed would result from fulfilling one's duty rather than following one's desires. Those idealized beliefs were only the Ghosts of the past, haunting the present.

In An Enemy of the People (1882), Ibsen went even further. In earlier plays, controversial elements were important and even pivotal components of the action, but they were on the small scale of individual households. In An Enemy, controversy became the primary focus, and the antagonist was the entire community. One primary message of the play is that the individual, who stands alone, is more often "right" than the mass of people, who are portrayed as ignorant and sheeplike. The Victorian belief was that the community was a noble institution that could be trusted, a notion Ibsen challenged. In An Enemy of the People Ibsen chastised not only the right wing or 'Victorian' elements of society but also the liberalism of the time. He illustrated how people on both sides of the social spectrum could be equally self-serving. An Enemy of the People was written as a response to the people who had rejected his previous work, Ghosts. The plot of the play is a veiled look at the way people reacted to the plot of Ghosts. The protagonist is a doctor, a pillar of the community. The town is a vacation spot whose primary draw is a public bath. The doctor discovers that the water used by the bath is being contaminated when it seeps through the grounds of a local tannery. He expects to be acclaimed for saving the town from the nightmare of infecting visitors with disease, but instead he is declared an 'enemy of the people' by the locals, who band against him and even throw stones through his windows. The play ends with his complete ostracism. It is obvious to the reader that disaster is in store for the town as well as for the doctor, due to the community's unwillingness to face reality.

As audiences by now expected of him, his next play again attacked entrenched beliefs and assumptions—but this time his attack was not against the Victorians but against overeager reformers and their idealism. Always the iconoclast, Ibsen was equally willing to tear down the ideologies of any part of the political spectrum, including his own.

The Wild Duck (1884) is considered by many to be Ibsen's finest work, and it is certainly the most complex. It tells the story of Gregers Werle, a young man who returns to his hometown after an extended exile and is reunited with his boyhood friend Hjalmar Ekdal. Over the course of the play the many secrets that lie behind the Ekdals' apparently happy home are revealed to Gregers, who insists on pursuing the absolute truth, or the "Summons of the Ideal". Among these truths: Gregers' father impregnated his servant Gina, then married her off to Hjalmar to legitimize the child. Another man has been disgraced and imprisoned for a crime the elder Werle committed. And while Hjalmar spends his days working on a wholly imaginary "invention", his wife is earning the household income.

Ibsen displays masterful use of irony: despite his dogmatic insistence on truth, Gregers never says what he thinks but only insinuates, and is never understood until the play reaches its climax. Gregers hammers away at Hjalmar through innuendo and coded phrases until he realizes the truth; Gina's daughter, Hedvig, is not his child. Blinded by Gregers' insistence on absolute truth, he disavows the child. Seeing the damage he has wrought, Gregers determines to repair things, and suggests to Hedvig that she sacrifice the wild duck, her wounded pet, to prove her love for Hjalmar. Hedvig, alone among the characters, recognizes that Gregers always speaks in code, and looking for the deeper meaning in the first important statement Gregers makes which does not contain one, kills herself rather than the duck in order to prove her love for him in the ultimate act of self-sacrifice. Only too late do Hjalmar and Gregers realize that the absolute truth of the "ideal" is sometimes too much for the human heart to bear.

Interestingly, late in his career Ibsen turned to a more introspective drama that had much less to do with denunciations of Victorian morality. In such later plays as Hedda Gabler (1890) and The Master Builder (1892) Ibsen explored psychological conflicts that transcended a simple rejection of Victorian conventions. Many modern readers, who might regard anti-Victorian didacticism as dated, simplistic and even clichéd, have found these later works to be of absorbing interest for their hard-edged, objective consideration of interpersonal confrontation. Hedda Gabler and The Master Builder centre on female protagonists whose almost demonic energy proves both attractive and destructive for those around them. Hedda Gabler is probably Ibsen's most performed play, with the title role regarded as one of the most challenging and rewarding for an actress even in the present day. There are a few similarities between Hedda and the character of Nora in A Doll's House, but many of today's audiences and theatre critics feel that Hedda's intensity and drive are much more complex and much less comfortably explained than what they view as rather routine feminism on the part of Nora.

Ibsen had completely rewritten the rules of drama with a realism which was to be adopted by Chekhov and others and which we see in the theatre to this day. From Ibsen forward, challenging assumptions and directly speaking about issues has been considered one of the factors that makes a play art rather than entertainment. Ibsen returned to Norway in 1891, but it was in many ways not the Norway he had left. Indeed, he had played a major role in the changes that had happened across society. The Victorian Age was on its last legs, to be replaced by the rise of Modernism not only in the theatre, but across public life.

Death

Ibsen died in Kristiania (now Oslo) on May 23, 1906 after a series of strokes. When his nurse assured a visitor that he was a little better, Ibsen sputtered "On the contrary" and died. In 2006 the 100th anniversary of Ibsen's death was commemorated in Norway and many other countries, and the year dubbed the "Ibsen year" by Norwegian authorities. On the occasion of the hundred-year commemoration of Ibsen's death, 23 May 1906, the Ibsen Museum reopened a completely restored writer's home with the original interior, original colours and decor. In May 2006 also a biographical puppet production of Ibsen's life named ' The Death of Little Ibsen' debuted at New York City's Sanford Meisner Theatre.

List of works

|

|