Mary I of England

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: British History 1500-1750; Monarchs of Great Britain; Religious figures and leaders

- Mary Tudor is the name of both Mary I of England and her aunt, Mary Tudor, Queen of France.

| Mary I | |

|---|---|

| Queen of England and Ireland, Queen Consort of Aragon, Castile, and Naples, Consort of the Spanish Netherlands. (more...) | |

|

|

| Portrait of Mary I painted in 1554 by Antonius Mor Museum of Prado, Madrid |

|

| Reign | 19 July 1553– 17 November 1558 |

| Coronation | 1 October 1553 |

| Predecessor | Jane de facto; Edward VI de jure |

| Successor | Elizabeth I |

| Consort | Philip II of Spain |

|

Detail Titles and styles |

|

| HM The Queen Lady Mary Tudor Princess Mary |

|

| Royal house | House of Tudor |

| Father | Henry VIII |

| Mother | Catherine of Aragon |

| Born | 18 February 1516 Palace of Placentia, Greenwich |

| Died | 17 November 1558 (aged 42) Saint James's Palace, London |

| Burial | 14 December 1558 Westminster Abbey, London |

Mary I ( 18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), was Queen of England and Queen of Ireland from 19 July 1553 until her death. The fourth crowned monarch of the Tudor dynasty, she is remembered for restoring England to Roman Catholicism after succeeding her short-lived half brother, Edward VI, to the English throne. In the process, she had almost three hundred religious dissenters burned at the stake in the Marian Persecutions, resulting in her being called Bloody Mary. Her re-establishment of Roman Catholicism was reversed by her successor and half-sister, Elizabeth I.

Childhood and early years

Mary was the only child of Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon to survive infancy. A stillborn sister and three short-lived brothers, including Henry, Duke of Cornwall, had preceded her. Through her mother, she was a granddaughter of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. She was born at the Palace of Placentia in Greenwich, London, on Monday 18 February 1516. She was baptised on the following Thursday with Thomas Cardinal Wolsey standing as her godfather. Mary was a sickly child who had poor eyesight, sinus conditions and bad headaches.

Despite her health problems Mary was a precocious child. A great part of the credit for her early education likely came from her mother, who consulted the Spanish scholar Juan Luis Vives upon the subject and was Mary's first instructor in Latin. Mary also studied Greek, science, and music. In July 1521, when scarcely five and a half years old, she entertained some visitors with a performance on the virginal (a smaller harpsichord). Henry VIII doted on his daughter and would boast in company, "This girl never cries". When Mary was nine years old, Henry gave her her own court at Ludlow Castle and many of the Royal Prerogatives normally only given to a (male) Prince of Wales, even calling her the Princess of Wales. In 1526, Mary was sent to Wales to preside over the Council of Wales and the Marches. Despite this obvious affection, Henry was deeply disappointed that his marriage had produced no sons.

Throughout her childhood Henry negotiated potential marriages for Mary. When she was only two years old she was promised to the Dauphin Francis, son of Francis I, King of France, but after three years, the contract was repudiated. In 1522, she was instead contracted to marry her first cousin, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, then 22, by the Treaty of Windsor. Within a few years, however, the engagement was broken off. It was then suggested that Mary wed the Dauphin's father Francis I, who was eager for an alliance with England. A marriage treaty was signed which provided that Mary should marry either Francis I or his second son Henry, Duke of Orléans. However, Cardinal Wolsey, Henry VIII's chief adviser, managed to secure an alliance without the marriage.

Meanwhile, the marriage of Mary's parents was in jeopardy because Catherine had failed to provide Henry the male heir he desired. Henry attempted to have his marriage to her annulled, but to his disappointment, Pope Clement VII refused his requests. Some contend that the Pope's decision was influenced by Charles V, Mary's former betrothed and her mother's nephew. Henry had claimed, citing biblical passages, that his marriage to Catherine was unclean because she had been previously married briefly, at age 16 to his brother Arthur, although there was some debate as to whether that marriage had been consummated. In 1533, Henry secretly married another woman, Anne Boleyn, and shortly thereafter, Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, formally declared the marriage with Catherine void and the marriage with Anne valid. Henry then broke with the Roman Catholic Church and declared himself head of the Church of England. As a consequence, Catherine lost the dignity of being queen and was demoted to Dowager Princess of Wales (a title she would have held as the widow of Arthur). Mary in turn was deemed illegitimate, and her place in the line of succession transferred to her half-sister, the future Elizabeth I, daughter of Anne Boleyn. She was styled "Lady Mary" rather than princess because of her illegitimate status.

Mary was expelled from Court, her servants dismissed from her service, and she was forced to serve as a lady-in-waiting to Elizabeth. Mary was not permitted to see her mother Catherine, nor attend her funeral in 1536. It is said that because of this treatment, Mary was very cold towards Elizabeth during Elizabeth's teenage years, deriding Anne Boleyn's execution and calling her a witch. Circumstances between Mary and her father worsened, and she attempted to reconcile with him by submitting to his authority as head of the Church of England. By this she repudiated papal authority, acknowledged that the marriage between her mother and father was unlawful, and accepted her own illegitimacy.

Mary may have expected her troubles to end when Anne Boleyn lost royal favour and was beheaded in 1536. Like Mary before, Elizabeth was downgraded to the status of Lady and removed from the line of succession. Within two weeks of Anne Boleyn's execution, Henry married Jane Seymour, who died shortly after giving birth to a son, the future Edward VI. Mary was godmother to her half-brother Edward and chief mourner at Jane Seymour's funeral. In return, Henry agreed to grant her a household, and Mary was permitted to reside in royal palaces. Her privy purse expenses for nearly the whole of this period have been published and show that Hatfield House, the Palace of Beaulieu (also called Newhall), Richmond and Hunsdon were among her principal places of residence. She was later awarded the Palace of Beaulieu as her own. When Mary reminded Henry VIII of Catherine of Aragon, he banished her to Beaulieu. He did the same to Elizabeth, but to the dismay of Mary, Elizabeth was sent to Hatfield.

In 1543 Henry married his sixth and last wife, Katharine Parr, who was able to bring the family closer together. The next year, through the Third Succession Act, Henry returned Mary and Elizabeth to the line of succession, being placed after Edward. Both women, however, remained legally illegitimate.

In 1547, Henry died and was succeeded by his son, Edward VI. Since Edward was still a child, rule passed to a regency council dominated by Protestants, who attempted to establish Protestantism throughout the country. As an example, the Act of Uniformity 1549 prescribed Protestant rites for church services, such as the use of Thomas Cranmer's new Book of Common Prayer. When Mary, who had remained faithful to Roman Catholicism, asked to be allowed to worship in private in her own chapel, she was refused. It was only after Mary appealed to her cousin Charles V that she was allowed to worship privately. Religious differences continued to be a problem between Mary and Edward, however. When Mary was in her thirties, she attended a reunion with Edward and Elizabeth for Christmas, where Edward embarrassed Mary and reduced her to tears in front of the court for "daring to ignore" his laws regarding worship.

Accession

| English Royalty |

|---|

| House of Tudor |

Royal Coat of Arms |

| Henry VIII |

| Henry, Duke of Cornwall |

| Mary I |

| Elizabeth I |

| Edward VI |

| Mary I |

On 6 July 1553, at the age of 15, the reigning king, Edward VI, died of tuberculosis. Edward did not want the crown to go to Mary, whom he feared would restore the Catholic faith and undo his reforms, as well as those of Henry VIII. For this reason, he planned to exclude her from the line of succession. However, his advisors told him that he could not disinherit only one of his sisters, but that he would have to disinherit Elizabeth as well, even though she embraced the Reformed faith and the Church of England. Guided by the John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland and perhaps others, Edward excluded both of his sisters from the line of succession in his will.

Edward VI and his advisors instead devised that he should be succeeded by Dudley's daughter-in-law Lady Jane Grey, the granddaughter of Henry VIII's younger sister Mary, Duchess of Suffolk. However, this exclusion was unlawful since (1) it was made by a minor and (2) it contradicted the Act of Succession. This latter act, passed in 1544, had restored Mary and Elizabeth to the line of succession. Around the time of Edward VI's death, Mary had been summoned back to London from Framlingham Castle in Suffolk, into which she had recently moved after having left her former residence at the Palace of Beaulieu. However, Mary initially hesitated; she suspected that this summons could be a pretext on which to capture her and, in so doing, facilitate Grey's accession to the throne.

On 10 July 1553, Lady Jane Grey assumed the throne as Queen of England. However, her support quickly eroded, which led to her being deposed only nine days later. In the wake of Grey's deposition, Mary rode triumphantly into London on a wave of popular support to assume the crown Grey left behind. For their part, Grey and Dudley were ultimately imprisoned in the Tower of London and executed. Mary feared that if left alive Lady Jane would be a rallying point for rebels who rejected Mary's rule.

One of Mary's first actions as Queen was to order the release of the Roman Catholic Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk and Stephen Gardiner from imprisonment in the Tower of London. At this time, the Duke of Northumberland was the only conspirator executed for high treason. Mary was left in a difficult position, as almost all the Privy Counsellors had been implicated in the plot to put Jane on the throne. She could only rely on Gardiner, whom she appointed both Bishop of Winchester and Lord Chancellor.

On 1 October 1553, Gardiner formally crowned Mary.

Reign

Spanish marriage

At age 37, Mary turned her attention to finding a husband and producing an heir, thus preventing the Protestant Elizabeth (still her successor under the terms of Henry VIII's will) from succeeding to the throne. Mary rejected Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon, as a prospect when her cousin Charles V suggested she marry his only son, the Spanish prince Philip, later Philip II of Spain. It is said that upon viewing a portrait of Philip, Mary declared herself to be in love with him.

Their marriage at Winchester Cathedral on 25 July 1554 took place just two days after their first meeting. Philip's view of the affair was entirely political (he admired her dignity but felt "no carnal love for her"), and it was extremely unpopular with the English. Lord Chancellor Gardiner and the House of Commons petitioned her to consider marrying an Englishman, fearing that England would be relegated to a dependency of Spain. This fear may have arisen from the fact that Mary was – excluding the brief, unsuccessful and controversial reigns of Jane and Empress Matilda – England's first Queen regnant.

Domestic politics

Insurrections broke out across the country when she insisted on marrying Philip, with whom she was in love. The Duke of Suffolk once again proclaimed that his daughter, Lady Jane Grey, was queen. In support of Elizabeth, Thomas Wyatt led a force from Kent that was not defeated until he had arrived at London. After the rebellions were crushed, the Duke of Suffolk, his daughter, Lady Jane Grey, and her husband were convicted of high treason and executed. Elizabeth, though protesting her innocence in the Wyatt affair, was imprisoned in the Tower of London for two months, then was put under house arrest at Woodstock Palace.

Mary married Philip on 25 July 1554, at Winchester Cathedral. Under the terms of the marriage treaty, Philip was to be styled "King of England", all official documents (including Acts of Parliament) were to be dated with both their names, and Parliament was to be called under the joint authority of the couple. Coins were also to show the heads of both Mary and Philip. The marriage treaty further provided that England would not be obliged to provide military support to Philip's father, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, in any war. Philip's powers, however, were extremely limited, and he and Mary were not true joint sovereigns like William and Mary.

Pregnancy

Mary, thinking she was pregnant, had thanksgiving services at the diocese of London in November 1554. This turned out to be the first of two phantom pregnancies. In reality, Mary had a cyst in her stomach. Philip persuaded his wife to permit Elizabeth's release from house arrest, probably so that he would be viewed favourably by her in case Mary died during childbirth. After only fourteen months, Philip found an excuse to leave for Spain.

Religion

As Queen, Mary was very concerned about religious issues. She had always rejected the break with Rome instituted by her father and the establishment of Protestantism by Edward VI. She had England reconcile with Rome and Reginald Cardinal Pole, the son of her governess the Countess of Salisbury and once considered a suitor, became Archbishop of Canterbury after Mary had his predecessor Thomas Cranmer executed. Mary would come to rely greatly on Pole for advice.

Edward's religious laws were abolished by Mary's first Parliament in the Statute of Repeal Act (1553). Church doctrine was restored to the form it had taken in the 1547 Six Articles.

Mary also persuaded Parliament to repeal the Protestant religious laws passed by Henry VIII. Getting their agreement took several years, and she had to make a major concession: tens of thousands of acres of monastery lands confiscated under Henry were not to be returned to the monasteries because the new landowners created by this distribution were very influential. This was approved by the Papacy in 1554. The Revival of the Heresy Acts were also passed in 1554. Mary also started currency reform to counteract the dramatic devaluation overseen by Thomas Gresham that had characterized the last few years of Henry's reign and the reign of Edward VI. These measures, however, were largely unsuccessful.

Persecutions

Numerous Protestant leaders were executed in the Marian Persecutions. Many rich Protestants chose exile, and around 800 left the country. The first to die were John Rogers ( 4 February 1555), Laurence Saunders ( 8 February 1555), Rowland Taylor ( 9 February 1555), and John Hooper, the Bishop of Gloucester ( 9 February 1555). The persecution lasted for almost four years. It is not known exactly how many died. John Foxe estimates in his Book of Martyrs that 284 were executed for their faith. The Marian persecutions are commemorated especially by bonfires in the town of Lewes in Sussex: there is a prominent martyrs' memorial outside St John's church at Stratford, London, to those Protestants burnt in Essex, and others in Christchurch Park Ipswich and the abbey grounds, Bury St Edmunds, to those executed in East and West Suffolk respectively.

Foreign policy

Henry VIII's creation of the Kingdom of Ireland in 1542 was not recognized by Europe's Catholic powers. In 1555 Mary obtained a papal bull confirming that she and Philip were the monarchs of Ireland, and thereby the Church accepted the personal link between the kingdoms of Ireland and England. Furthering the Tudor Reconquest of Ireland, the midlands counties of Laois and Offaly were shired and named after the new monarchs respectively as "Queen's County" and "King's County". Their principal towns were respectively named Maryborough (now Portlaoise) and Philipstown (now Daingean). Under Mary's reign, English colonists were settled in the Irish midlands to reduce the attacks on the Pale (the colony around Dublin).

Having inherited the throne of Spain upon his father's abdication, Philip returned to England from March to July 1557 to persuade Mary to support Spain in a war against France (the Italian Wars). There was much opposition to declaring war on France. There existed an old alliance between Scotland and France; French trade would be jeopardized; and England had a distinct lack of finances because of a bad economic legacy from the reign of Edward VI. As a result of her agreement to declare war (which violated the carefully-written marriage treaty), England became full of factions and seditious pamphlets of Protestant origin inflaming the country against the Spaniards. English forces fared badly in the conflict and as a result lost Calais, England's sole remaining continental possession, on 13 January 1558. Although this territory had recently become financially burdensome, the effects of its loss were ideological. Mary later lamented that when she died the words "Philip" and "Calais" would be found inscribed on her heart.

Commerce and revenue

The most prominent problem was the decline of the Antwerp cloth trade. Despite Mary's marriage to Philip, England did not benefit from their enormously lucrative trade with the New World. The Spanish guarded their trading revenue jealously, and Mary could not condone illegitimate trade (in the form of piracy) because she was married to a Spaniard. In an attempt to increase trade and rescue the English economy, Mary continued Northumberland's policy of seeking out new commercial ports outside Europe.

Financially, Mary was trying to reconcile between a modern form of government—with correspondingly higher spending—with a medieval system of collecting taxation and dues. A failure to apply new tariffs to new forms of imports meant that a key source of revenue was neglected. In order to solve this problem, Mary's government published the "Book of Rates" (1558), listing the tariffs and duties for every import. This publication was not reviewed until 1604. Mary also appointed William Paulet, 1st Marquess of Winchester as Surveyor of Customs and assigned him to oversee the revenue collection system.

Death

During her reign, Mary suffered two phantom pregnancies. It has been speculated that these could simply be a result of the pressure to produce an heir, though the physical symptoms (including lactation and the later loss of her eyesight) reported by Mary's attendants may be indicative of a hormonal disorder such as a pituitary tumour.

Mary decreed in her will that her husband Philip should be the regent during the minority of her child. No child, however, was born, and Mary died at age 42 at St. James's Palace on 17 November 1558. She was succeeded by her half-sister, who became Elizabeth I. Although her will stated that she wished to be buried next to her mother, Mary was interred in Westminster Abbey on 14 December in a tomb she eventually shared with Elizabeth. The Latin inscription on a marble plaque on their tomb (affixed there by James VI of Scotland when he succeeded Elizabeth to the throne of England as James I) translates to "Partners both in Throne and grave, here rest we two sisters, Elizabeth and Mary, in the hope of one resurrection".

Legacy

Although Mary enjoyed tremendous popular support and sympathy for her mistreatment during the earliest parts of her reign, she lost almost all of it after marrying Philip. The marriage treaty clearly specified that England was not to be drawn into any Spanish wars, but this guarantee proved meaningless. Philip spent most of his time governing his European territories, while his wife usually remained in England. After Mary's death, Philip became a suitor for Elizabeth's hand, but she refused him.

The persecution of Protestants earned Mary the appellation "Bloody Mary" although many historians believe Mary does not deserve all the blame. There is disagreement as to the number of people put to death during Mary's five-year reign. However, several notable clerics were executed; among them Thomas Cranmer, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Nicholas Ridley the former Bishop of London and the reformist Hugh Latimer. John Foxe vilified Mary in his Book of Martyrs, which may have been a biased account of the events, considering the high level of emotion at the time.

One popular tradition traces the nursery rhyme Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary to Mary's attempts to bring Roman Catholicism back to England, although it may well be about her cousin Mary, Queen of Scots.

Style and arms

Like Henry VIII and Edward VI, Mary used the style "Majesty", as well as "Highness" and "Grace". "Majesty", which Henry VIII first used on a consistent basis, did not become exclusive until the reign of Elizabeth I's successor, James I.

When Mary ascended the throne, she was proclaimed under the same official style as Henry VIII and Edward VI: "Mary, by the Grace of God, Queen of England, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, and of the Church of England and also of Ireland in Earth Supreme Head". The "supremacy phrase" at the end of the style was repugnant to Mary's Roman Catholic faith; from 1554 onwards, she omitted the phrase without statutory authority, which was not retroactively granted by Parliament until 1555.

Under Mary's marriage treaty with Philip II of Spain, the couple were jointly styled Queen and King. The official joint style reflected not only Mary's but also Philip's dominions and claims; it was "Philip and Mary, by the grace of God, King and Queen of England, France, Naples, Jerusalem, and Ireland, Defenders of the Faith, Princes of Spain and Sicily, Archdukes of Austria, Dukes of Milan, Burgundy and Brabant, Counts of Habsburg, Flanders and Tyrol". This style, which had been in use since 1554, was replaced when Philip inherited the Spanish Crown in 1556 with "Philip and Mary, by the Grace of God King and Queen of England, Spain, France, Jerusalem, both the Sicilies and Ireland, Defenders of the Faith, Archdukes of Austria, Dukes of Burgundy, Milan and Brabant, Counts of Habsburg, Flanders and Tyrol".

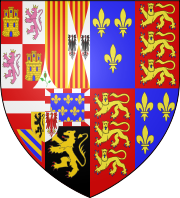

Mary I's arms were the same as those used by all her predecessors since Henry IV: Quarterly, Azure three fleurs-de-lys Or [for France] and Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or [for England]. Sometimes, Mary's arms were impaled (depicted side-by-side) with those of her husband.

Ancestors

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||