Roman Catholic Church

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Religious movements, traditions and organizations

The Roman Catholic Church, officially known as the Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church and represents over half of all Christians and one-sixth of the world's population. It is made up of one Western church (the Latin Rite) and 22 Eastern Catholic churches, divided into 2,782 jurisdictional areas around the world. The Church looks to the Pope, currently Benedict XVI, as its highest human authority in matters of faith, morality and Church governance. The Church community is composed of an ordained ministry and the laity. Either may be members of religious communities like the Dominicans, Carmelites, Jesuits and Salesians.

The Catholic Church defines its mission as spreading the message of Jesus Christ, found in the four Gospels, administering sacraments that aid the spiritual growth of its members and exercising charity. To further its mission, the Church operates programs and institutions throughout the world. They include schools, universities, hospitals, missions and shelters, as well as Catholic Relief Services, Caritas Internationalis and Catholic Charities that help the poor, families, the elderly and the sick.

Through Apostolic succession, the Church believes itself to be the continuation of the Christian community founded by Jesus in his consecration of Saint Peter. The Church has defined its doctrines through various ecumenical councils, following the example set by the first Apostles in the Council of Jerusalem. Catholic faith is summarized in the Nicene Creed and detailed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Catholic worship is ordered by the liturgy, which is regulated by Church authority. The Eucharist, one of seven Church sacraments and a key part of every Catholic Mass, is the centre of Catholic worship.

With a two thousand year history, the Church is the world's oldest and largest Christian institution. From at least the 4th century, it has played a prominent role in the history of Western civilization. In the 11th century, the Eastern, Orthodox Church and the Western, Catholic Church split, largely over disagreements regarding papal primacy. Eastern churches, which maintained or later re-established communion with Rome, form the Eastern Catholic Churches. In the 16th century, partly in response to the Protestant Reformation, the Church engaged in a substantial process of reform and renewal, known as the Counter-Reformation.

The Catholic Church maintains that it is the " one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church" founded by Jesus, but acknowledges that the Holy Spirit can make use of Christian communities separated from itself to bring people to salvation. The Church teaches that it is called by the Holy Spirit to work for unity among all Christians—a movement known as ecumenism. Modern challenges facing the Church include the rise of secularism and opposition to its pro-life stance on abortion, contraception and euthanasia.

Origin and mission

The Catholic Church traces its foundation to Jesus and the Twelve Apostles. It sees the bishops of the Church as the successors of the apostles and the pope in particular as the successors of Peter, the leader of the apostles. Catholics cite Jesus' words in the Gospel of Matthew to support this view: "... you are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church ... I will give you the keys to the kingdom of heaven. Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven; whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven." According to Catholic belief, the coming of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles in an event known by Christians as Pentecost brought this promised "church" fully into the world.

Scholars like Edward Norman note that the Catholic Church was founded by Jesus and that the historical record confirms that it was considered a Christian doctrinal authority from its beginning. John McManners, among other leading scholars, cites a letter from Pope Clement I to the church in Corinth (c. 95) as evidence of a presiding Roman cleric who exercised authority over other churches. Others, like Eamon Duffy, acknowledge the existence of a Christian community in Rome and that Peter and Paul "lived, preached and died" there but doubt that there was a ruling bishop in the Roman church in the first century, and question the concept of apostolic succession. Duffy described the second-century list of popes by Irenaeus as "suspiciously tidy", and stated that "There is no sure way to settle on a date by which the office of ruling bishop had emerged in Rome, and so to name the first pope, but the process was certainly complete by the time of Anicetus in the mid-150s, when Polycarp, the aged bishop of Smyrna, visited Rome, and he and Anicetus debated amicably the question of the date of Easter".

The Church believes that its mission is founded upon Jesus' command to his followers to spread the faith across the world: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you: and Lo, I am with you always, until the close of the age". Pope Benedict XVI summarized the Church's mission as a threefold responsibility to proclaim the word of God, celebrate the sacraments, and exercise the ministry of charity. He has stated that these duties presuppose each other and are thus inseparable. As part of its ministry of charity the Church runs Catholic Relief Services, Catholic Charities, Caritas Internationalis, Catholic schools, universities, hospitals, shelters and ministries to the poor, as well as ministries to families, the elderly and the marginalized. Through these programs the Church applies the tenets of Catholic social teaching and tends to the corporal and spiritual needs of human beings.

Beliefs

The Catholic Church's beliefs are detailed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. The Catholic Church is trinitarian since it believes that there is one eternal God who exists as a mutual indwelling of three persons: the Father, the Son Jesus and the Holy Spirit. Catholic teachings have been refined and clarified over the centuries by councils of the Church convened by Church leaders at important points throughout history. The first such council, the Council of Jerusalem, was convened by the apostles around the year 50. The most recent was the Second Vatican Council, which closed in 1965. The Nicene Creed dating back to the First Council of Nicaea (325), is the core statement of Catholic Christian belief. This creed is recited at Sunday Masses and is also the central statement of belief of many other Christian denominations. Eastern Orthodox Christians do not accept the filioque clause. Protestant churches vary in their beliefs, but generally accept the Nicene Creed with reservations regarding the term "Catholic". They generally differ from the Catholic Church regarding the authority of the pope, church tradition, and on issues pertaining to divine grace, good works and salvation.

Teaching authority

The Catholic Church believes that it is guided by the Holy Spirit and so protected from falling into doctrinal error. It bases this belief on biblical promises that Jesus made to his apostles. In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus tells Peter, "the gates of the netherworld shall not prevail against [the church]", and in the Gospel of John, Jesus says, "... when He comes, the Spirit of truth, He will guide you to all truth".

The Church teaches that the Holy Spirit reveals God's truth through Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition and the Magisterium. The sacred scriptures consist of the 73 books of the Catholic Bible. These are made up of those contained in the Greek version of the Old Testament—known as the Septuagint—and the 27 New Testament writings found in the Codex Vaticanus and listed in Athanasius' Thirty-Ninth Festal Letter. Sacred Tradition consists of those teachings believed by the Church to have been handed down since the time of the Apostles. Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition are collectively known as the "deposit of faith". These are in turn interpreted by the Magisterium, or the teaching authority of the Church. The Magisterium includes infallible pronouncements of the pope, pronouncements of ecumenical councils, and those of the college of bishops acting in union with the pope to define truths or to condemn interpretations of scripture believed to be false.

According to the Catechism, Jesus instituted seven sacraments and entrusted them to the Church. These are Baptism, Confirmation, the Eucharist, Penance, Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders and Holy Matrimony. Sacraments are visible rituals which Catholics see as providing God's grace to all those who receive them with the proper mindset or disposition ( ex opere operato). Differing liturgical traditions, or rites, exist throughout the worldwide Church. These reflect historical and cultural diversity rather than a diversity in beliefs. The most commonly used is the Western or Latin rite. Others are the Byzantine rite, the Alexandrian or Coptic rite, the Syriac, Armenian, Maronite and Chaldean rites.

God the Father, original sin and Baptism

Catholic belief holds that God is the source and creator of nature and all that exists. as expressed in the opening statement of the Nicene Creed, "We believe in one God, the Father, the Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all that is seen and unseen ...". The Church perceives him as a loving and caring God who is involved in the world and in people's lives and who desires his creatures to love him and to love each other. Before the creation of mankind, however, the scriptures teach that God made spiritual beings called angels. In an event known as the "fall of the angels", a number of them chose to rebel against God and his reign. The leader of this rebellion has been called "Lucifer", "Satan" and the devil among other names. The sin of pride, considered one of seven deadly sins, is attributed to Satan for wishing to be equal to God. One of these fallen angels is believed to have tempted the first humans, Adam and Eve, whose act of original sin brought suffering and death into the world.

This event is known as the Fall of Man and according to Catholic belief, left humanity isolated from their original state of intimacy with God. The Catechism states that the description of the fall described in Genesis 3 uses figurative language, but affirms "... a deed that took place at the beginning of the history of man" and resulted in "a deprivation of original holiness and justice" that makes each person "subject to ignorance, suffering, and the dominion of death: and inclined to sin". The Church believes that people can be cleansed of original sin and all personal sins through Baptism. This sacramental act of cleansing admits one as a full member of the natural and supernatural Church and is only conferred once in a person's lifetime.

Jesus, sin and Penance

In the messianic texts of the Jewish Tanakh which make up much of the Christian Old Testament, Christians believe God promises to send his people a savior. The Church believes that this savior was Jesus who is described in the Nicene Creed as "... the only begotten son of God, ... one in being with the Father. Through him all things were made ...". In an event known as the Incarnation, the Church teaches that God descended from heaven for the salvation of humanity, and became man through the power of the Holy Spirit and was born of a virgin Jewish girl named Mary. Jesus' mission on earth is believed to have included giving people his word and example to follow, as recorded in the four Gospels. The Church teaches that following the example of Jesus helps believers to become closer to him, and therefore to grow in true love, freedom, and the fullness of life. Sinning is considered to be the opposite to following Jesus, robbing people of their resemblance to God and turning their souls away from his love. Per Catholic teaching, people can sin by failing to obey the Ten Commandments, failing to love God, or failing to love other people. Some sins are held to be more serious than others. Sins range from lesser or venial sins, to grave or mortal sins which end a person's relationship with God. Through the passion of Jesus and his crucifixion, the Church teaches that all people have an opportunity for forgiveness and freedom from sin, and so can be reconciled to God. John the Baptist, respected by the Church as a prophet, called Jesus "the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world" in reference to the ancient Jewish practice of offering sacrificial lambs to God to obtain some greater good. By reconciling with God and following Jesus' words and deeds, the Church believes one can enter the Kingdom of God which is not a place but a state of being defined by the Church as "... the reign of God over people's hearts and lives."

Since Baptism can be received only once, the sacrament of Penance (informally known as Confession) is the principal means by which Catholics can obtain forgiveness for subsequent sin and receive God's grace and assistance not to sin again. Catholics believe Jesus gave the apostles special authority to forgive sins in God's name based on Jesus' words to his disciples in the Gospel of John 20:21–23. A penitent confesses his sins to the priest, who may then offer advice. After the priest has imposed a particular penance to be performed, the penitent then prays an act of contrition and the priest administers absolution, formally forgiving the person of his sins. A priest is forbidden under penalty of excommunication to reveal any sin or disclosure heard under the seal of confession. Penance helps prepare Catholics before they can licitly receive the sacraments of Confirmation and the Eucharist.

Holy Spirit and Confirmation

Jesus told his apostles that after his death and resurrection he would send them the "Advocate", the " Holy Spirit", who " ...will teach you everything and remind you of all that (I) told you". In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus told his disciples "If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him!"

The Nicene Creed states that the Holy Spirit is one with God the Father and God the Son. Thus the Church teaches that receiving the Holy Spirit is an act of receiving God. Through the sacrament of Confirmation, Catholics ask for and are taught by the Church to receive the Holy Spirit. Confirmation is sometimes called the "sacrament of Christian maturity" and is believed to increase and deepen the grace received at Baptism. Spiritual graces or gifts of the Holy Spirit may include the wisdom to see and follow God's plan, as well as judgment, love, courage, knowledge, reverence and rejoicing in the presence of God. The corresponding fruits of the Holy Spirit are love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self control.

To be licitly confirmed, Catholics must be in a state of grace, in that they cannot be conscious of having committed a mortal sin. They must also have prepared spiritually for the sacrament, chosen a sponsor or godparent for spiritual support, and selected a saint to be their special patron and intercessor. Baptism in the Eastern rites, including infant baptism, is immediately followed by the reception of Confirmation and the Eucharist.

Nature of the Church and social teaching

Catholic belief holds that the Church " ...is the continuing presence of Jesus on earth." Jesus told his disciples to "Remain in me, as I remain in you ... I am the vine, you are the branches." In Catholic interpretation, the term "Church" refers to the people of God, who abide in Jesus and who, " ...nourished with the Body of Christ, become the Body of Christ." Catholic teaching maintains that the Church exists simultaneously on earth, in purgatory (Church suffering), and in heaven (Church triumphant). Thus the Virgin Mary assumed into heaven and the saints are alive and part of the living Church. This unity of the Church in heaven and on earth is the " Communion of Saints".

While the Catholic Church believes and teaches that it is the " one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church" founded by Jesus, it also holds that the Holy Spirit can work through other churches to bring people to salvation. In its apostolic constitution Lumen Gentium, the Church acknowledges that the Holy Spirit is active in diverse Christian churches and communities, and that Catholics are called to work for unity among all Christians.

The Church operates numerous social ministries throughout the world but teaches that individual Catholics are required to practice spiritual and corporal works of mercy as well. Corporal works of mercy include feeding the hungry, welcoming strangers, immigrants or refugees, clothing the naked, taking care of the sick and visiting those in prison. Spiritual works require the Catholic to share their knowledge with others, to give advice to those who need it, comfort those who suffer, have patience, forgive those who hurt them, give correction to those who need it and pray for the living and the dead. In conjunction with the work of mercy to visit the sick, the Church offers the sacrament of Anointing of the Sick, performed only by a priest who will anoint with oil the head and hands of the ill person and pray a special prayer for them while laying on hands.

Church teaching on works of mercy and the new social problems of the industrial era led to the development of Catholic social teaching. Emphasizing human dignity, it criticizes elements of both capitalism and socialism and commits Catholics to the welfare of others. The seven main themes are respect for human life and the dignity of each person, the strengthening of the family unit, respect for the rights and responsibilities of each person, the care for the poor, the rights and dignity of the worker, and, the subsidiarity and solidarity of all humans as one family. Modern application of Catholic social teaching has resulted in significant Church efforts to fight what it sees as violations of immigrant, worker, and family rights. In addition, the Church is known for its staunch opposition to abortion and euthanasia. Further matters of concern have included capital punishment and environmental issues.

Final judgment and afterlife

Catholic teaching includes belief in an afterlife as described in the final statement of the Nicene Creed, "We look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come." The Church teaches that each soul will be judged by Jesus immediately after death and receive a particular judgment based on the deeds of their earthly life. Chapter 25:35–46 of the Gospel of Matthew underpins the Catholic belief that a day will also come when Jesus will sit in a universal judgment of all mankind. The Church teaches that this final judgment will bring an end to human history and mark the beginning of a new and better heaven and earth ruled by God in righteousness.

There are three states of afterlife in Catholic belief. Purgatory is a temporary condition for the purification of souls who, although saved, are not free enough from sin to enter directly into heaven. It is a state requiring penance and purgation of sin through God's mercy aided by the prayers of others. Heaven is a time of glorious union with God and a life of unspeakable joy that lasts forever. Finally, those who chose to live a sinful and selfish life, did not repent, and fully intended to persist in their ways are sent to hell, an everlasting separation from God. The Church teaches that no one is condemned to hell without having freely decided to reject God and his love. He predestines no one to hell and no one can determine whether anyone else has been condemned. Catholicism teaches that through God's mercy a person can repent at any point before death and be saved "like the good thief who was crucified next to Jesus".

Prayer and worship

In the Catholic Church, a distinction is made between the formal, public liturgy and other prayers or devotions. The liturgy is regulated by Church authority and consists of the Eucharist and Mass, the other sacraments, and the Liturgy of the Hours. All Catholics are expected to participate in the liturgical life of the Church but individual or communal prayer and devotions, while encouraged, are a matter of personal preference. The Church provides a set of precepts that every Catholic is expected to follow. These set a minimum standard for personal prayer and require the Catholic to attend Mass on Sundays, confess sins at least once a year, receive the Eucharist at least during Easter season, observe days of fasting and of abstinence as established by the Church, and help provide for the Church's needs.

Eucharist

The Eucharist, also known as Holy Communion, or the Lord's Supper, is celebrated at each Mass. This sacrament is considered to be the centre of Catholic worship. The Church believes that at the Last Supper, Jesus ratified a New Covenant with humanity by instituting the Eucharist and that the bread and wine brought to the altar at each Mass are changed through the power of the Holy Spirit into the true body and the true blood of Christ through transubstantiation. The Eucharist is distributed to worshippers through the eating of the consecrated unleavened bread, or bread-like wafer, or the drinking of consecrated wine from a common cup. Catholicism teaches that just as God's first covenant or solemn agreement with Moses and the Hebrew people was sealed with the blood of sacrificial animals, his new covenant with humanity was sealed with the blood of Jesus. The words of institution for this sacrament are found in the three synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, as well as in I Corinthians; "Then he took the bread, said the blessing, broke it, and gave it to them, saying, 'This is my body, which will be given for you; do this in memory of me.' " "Then he took a cup, gave thanks, and gave it to them, saying, 'Drink from it, all of you, for this is my blood of the covenant, which will be shed on behalf of many for the forgiveness of sins.' " The New Covenant is, according to Catholic teaching, celebrated and renewed in the Eucharist.

The celebration of the Eucharist in the Eastern Catholic Churches is termed Divine Liturgy. Variations in this liturgy between the different Eastern Churches reflect different cultural traditions. The ordinary form of the Eucharist in the Latin rite, the Mass of Paul VI, is most often celebrated in the vernacular. It is separated into two parts. The first, called Liturgy of the Word, consists of readings from the Old and New Testaments, a Gospel passage and the priest's homily or explanation of one of those passages. The second part, called Liturgy of the Eucharist is the celebration of the Eucharist. According to professor Alan Schreck, in its main elements and prayers, the Catholic Mass celebrated today "bears striking resemblance" to the form of the Mass described in the Didache and First Apology of Justin Martyr in the late 1st and early 2nd centuries.

An alternate or extraordinary form of Mass, celebrated primarily in Latin, is that used prior to the Second Vatican Council. Called the Tridentine Mass, it derives from the missal promulgated by Pope Pius V after the Council of Trent. It was intended to reaffirm, in opposition to Protestant belief, that the Mass is the same sacrifice of Jesus' death as the one he suffered on Calvary. Although this form was superseded by the vernacular as the primary form after the Second Vatican Council, it was not forbidden; it was offered by an indult since Pope John Paul II's 1988 motu proprio, Ecclesia Dei and can now be said by any Roman rite priest according to Pope Benedict XVI's 2007 motu proprio, Summorum Pontificum.

Because the Church teaches that Christ is present in the Eucharist, there are strict rules about its celebration and reception. The ingredients of the bread and wine used in the Mass are specified and Catholics must abstain from eating for one hour before receiving Communion. Those who are conscious of being in a state of mortal sin are forbidden from this sacrament unless they have received absolution through the sacrament of Penance. According to Church belief, receiving the Eucharist forgives venial sins. Because the Church respects their celebration of the Mass as a true sacrament, intercommunion with the Eastern Orthodox in "suitable circumstances and with Church authority" is both possible and encouraged. Although the same is not true for Protestant churches, in circumstances of grave necessity, Catholic ministers may give the sacraments of Eucharist, Penance and Anointing of the Sick to Protestants if they freely ask for them, truly believe what the Catholic Church teaches regarding the sacraments, and have the proper disposition to receive them. Catholics may not receive communion in Protestant churches because of their different beliefs and practices regarding Holy Orders and the Eucharist.

Liturgy of the Hours and the liturgical year

In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus instructs his disciples to "pray always". The Liturgy of the Hours, or Divine Office, is the Church's effort to respond to this request. It is considered to be an extension of the celebration of the Mass and is the official daily liturgical prayer of the Church. It makes particular use of the Psalms as well as readings from the New and Old Testament, and various prayers. It is an adaptation of the ancient Jewish practice of praying the Psalms at certain hours of the day or night. Catholics who pray the Liturgy of the Hours use a set of books issued by the Church that has been called a breviary. By canon law, priests and deacons are required to pray the Liturgy of the Hours each day. Religious orders often make praying the Liturgy of the Hours a part of their rule of life; the Second Vatican Council encouraged the Christian laity to take up the practice.

The liturgical year is the annual calendar of the Catholic Church. The Church sets aside certain days and seasons of each year to recall and celebrate various events in the life of Christ. The Byzantine liturgical year, like the former imperial calendar, starts on 1 September, while in the Western Church the liturgical year begins with Advent, the time of preparation for both the celebration of Jesus' birth, and his expected second coming at the end of time. Christmastide follows, beginning on the night of 24 December (Christmas Eve), and ending with the feast of the baptism of Jesus. Lent is the period of purification and penance that in the Latin church begins on Ash Wednesday and ends on Holy Thursday. (In the Byzantine Catholic churches, "Great Lent" begins on Clean Monday and, counting the Sundays as part of the forty days of Lent, ends on Lazarus Saturday, being followed immediately by Great and Holy Week.) The Holy Thursday evening Mass of the Lord's Supper marks the beginning of the Easter Triduum which includes Good Friday, Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday. These days recall Jesus' last supper with his disciples, death on the cross, burial and resurrection. The seven-week liturgical season of Easter immediately follows the Triduum climaxing at Pentecost. This recalls the descent of the Holy Spirit upon Jesus' disciples after the Ascension of Jesus. The rest of the liturgical year is known as Ordinary Time.

Devotional life, prayer, Mary and the saints

In addition to the Mass, the Catholic Church considers prayer to be one of the most important elements of Christian life. The Church considers personal prayer a Christian duty, one of the spiritual works of mercy and one of the principal ways its members nourish a relationship with God. The Catechism identifies three types of prayer: vocal prayer (sung or spoken), meditation and contemplative prayer. Quoting from the early church father John Chrysostom regarding vocal prayer, the Catechism states, "Whether or not our prayer is heard depends not on the number of words, but on the fervor of our souls." Meditation is prayer in which the "mind seeks to understand the why and how of Christian life, in order to adhere and respond to what the Lord is asking." Contemplative prayer is being with God, taking time to be close to and alone with him. Three of the most common devotional prayers of the Catholic Church are The Lord's Prayer, the Rosary and Stations of the Cross. These prayers are most often vocal, yet always meditative and contemplative. Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament is a common form of contemplative prayer, whereas Benediction is a common vocal method of prayer. Lectio divina, which means "sacred reading", is a form of meditative prayer. The Church encourages patterns of prayer intended to develop into habitual prayer. This includes such daily prayers as grace at meals, the Rosary, or the Liturgy of the Hours, as well as the weekly rhythm of Sunday Eucharist and the observation of the year-long liturgical cycle.

Prayers and devotions to the Virgin Mary and the saints are a common part of Catholic life but are distinct from the worship of God. Explaining the intercession of saints, the Catechism states that the saints "... do not cease to intercede with the Father for us ... so by their fraternal concern is our weakness greatly helped." The Church holds Mary, as ever Virgin and Mother of God". in special regard. She is believed to have been conceived without original sin, and was assumed into heaven. These dogmas, focus of Roman Catholic Mariology, are considered infallible. She is honored with many titles such as Queen of Heaven. Pope Paul VI called her Mother of the Church, because by giving birth to Christ, she is considered to be the spiritual mother to each member of the Body of Christ. Because of her influential role in the life of Jesus, prayers and devotions, such as the Rosary, the Hail Mary, the Salve Regina and the Memorare are old Catholic practices. Pilgrimages to Marian shrines such as Lourdes and Fátima are popular devotions. The Church celebrates several liturgical Marian feasts throughout the Church Year.

Church organization and community

Although the Church considers Jesus to be its ultimate spiritual head, as an earthly organization its spiritual head and leader is the pope. The pope governs from Vatican City in Rome, a sovereign state of which he is also the civil head of state. Each pope is elected for life by the College of Cardinals, a body composed of bishops and priests who have been granted the status of Cardinal by previous popes. The cardinals, who also serve as papal advisors, may select any male member of the Church to reign as pope, but if not already ordained as a bishop, such ordination must occur before the candidate can take papal office. The pope is assisted in the administration of the Church by the Roman Curia, or civil service. The Church community is governed according to formal regulations set out in the Code of Canon Law. The official language of the Church is Latin, however Italian is the working language of the Vatican administration.

Worldwide, the Catholic Church comprises a Western or Latin and 22 Eastern Catholic autonomous particular churches. The Latin Church divides into jurisdictional areas known as dioceses, or eparchies in the Eastern Church. Each is headed by a bishop, patriarch or eparch, appointed by the pope. By 2007, including both dioceses and eparchies, there were 2,782 sees. Each diocese is divided into individual communities called parishes, which are staffed by one or more priests. The community is made up of ordained members and the laity. Members of religious orders such as nuns, friars and monks are considered lay members unless individually ordained as priests.

Ordained members and Holy Orders

Lay men become ordained through the sacrament of Holy Orders, and form a three-part hierarchy of bishops, priests and deacons. As a body the College of Bishops are considered to be the successors of the apostles. Along with the pope, the College includes all the cardinals, patriarchs, primates, archbishops and metropolitans of the Church. Only bishops are able to perform the sacrament of Holy Orders, and Confirmation is ordinarily reserved to them as well (though priests may do it under special circumstances). While bishops are responsible for teaching, governing and sanctifying the faithful of their diocese, priests and deacons have these same responsibilities at a more local level, the parish, subordinate to the ministry of the bishop. Priests, bishops and deacons preach, teach, baptize, witness marriages and conduct wake and funeral services, but only priests and bishops may celebrate the Eucharist or administer the sacraments of Penance and Anointing of the Sick.

Although married men may become deacons, only celibate men are ordained as priests in the Latin Rite. Clergy who have converted from other denominations are sometimes excepted from this rule. The Eastern Catholic Churches ordain both celibate and married men. All rites of the Catholic Church maintain the ancient tradition that, after ordination, marriage is not allowed. Men with transitory homosexual leanings may be ordained deacons following three years of prayer and chastity, but homosexual men who are sexually active, or those who have deeply rooted homosexual tendencies cannot be knowingly ordained.

All programs for the formation of men to the Catholic priesthood are governed by Canon Law. They are designed by national bishops' conferences such as the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and vary slightly from country to country. The conferences consult Vatican documents such as Pastores Dabo Vobis, Novo Millennio Ineunte, Optatam Totius and others to create these programs. In some countries, priests are required to have a college degree plus another four years of full time theological study in a seminary. In other countries a degree is not strictly required, but seminary education is longer. Candidates for the priesthood are also evaluated in terms of human, spiritual and pastoral formation. The sacrament of Holy Orders is always conferred by a bishop through the laying-on of hands, following which the newly ordained priest is formally clothed in his priestly vestments.

Because the Twelve Apostles chosen by Jesus were all male, only men may be ordained in the Catholic Church. While this position on an all male priesthood has been criticized as evidence of a discriminatory attitude toward women, the Church believes that Jesus called women to different yet equally important vocations in Church ministry. Pope John Paul II, in his apostolic letter Christifideles Laici, states that women have specific vocations reserved only for the female sex, and are equally called to be disciples of Jesus. This belief in different and complementary roles between men and women is exemplified in Pope Paul VI's statement "If the witness of the Apostles founds the Church, the witness of women contributes greatly towards nourishing the faith of Christian communities".

Lay members, Marriage

The laity consists of those Catholics who are not ordained clergy. Saint Paul compared the diversity of roles in the Church to the different parts of a body—all being important to enable the body to function. The Church therefore considers that lay members are equally called to live according to Christian principles, to work to spread the message of Jesus, and to effect change in the world for the good of others. The Church calls these actions participation in Christ's priestly, prophetic and royal offices. Marriage, the single life and the consecrated life are lay vocations. The sacrament of Holy Matrimony in the Latin rite is the one sacrament not conferred by a priest or bishop. The couple desiring marriage act as the ministers of the sacrament while the priest or deacon serves as witness. In Eastern rites, the priest or bishop administers the sacrament after the spouses grant mutual consent. Church law makes no provision for divorce, however annulment may be granted in strictly defined circumstances. Since the Church condemns all forms of artificial birth control, married persons are expected to be open to new life in their sexual relations. Natural family planning is approved.

Lay ecclesial movements consist of lay Catholics organized for purposes of teaching the faith, cultural work, mutual support or missionary work. Such groups include: Communion and Liberation, Neocatechumenal Way, Regnum Christi, Opus Dei, Life Teen and many others. Some non-ordained Catholics practice formal, public ministries within the Church. These are called lay ecclesial ministers, a broad category which may include pastoral life coordinators, pastoral assistants, youth ministers and campus ministers.

Religious orders

Both the ordained and the laity may enter the religious or consecrated life—either as monks or nuns if cloistered, or friars and sisters if not. A candidate takes vows confirming their desire to follow the three evangelical counsels of chastity, poverty and obedience.

The majority of those wishing to enter the consecrated life join one of the religious institutes which are also referred to as monastic or religious orders. They follow a common rule such as the Rule of St Benedict and agree to live under the leadership of a superior. They usually live together in groups of various sizes as a community although occasionally an individual is given permission to live as a hermit, or to reside elsewhere, for example as a serving priest or chaplain. Examples of religious institutes include the Sisters of Charity, Dominicans, Franciscans, Carmelites, Cistercians, Marist Brothers, Paulist Fathers and the Society of Jesus, but there are many others. Tertiaries are laypersons who live according to the third rule of orders such as the Franciscans or Carmelites, either within a religious community or outside. Although all tertiaries make a public profession, participate in the good works of their order and can wear the habit, they are not bound by public vows unless they live in a religious community. The Church recognizes several other forms of consecrated life, including secular institutes, societies of apostolic life and consecrated widows and widowers. It also makes provision for the approval of new forms.

Membership

According to canon law, membership of the Catholic Church is attained through Baptism. For those baptized as children, First Communion is a particular rite of passage, when, following instruction, they are allowed to receive the sacrament of the Eucharist for the first time. Christians baptized outside of the Catholic Church or those never baptized may be received by participating in a formation program such as the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults. In all rites, after going through formation and making a profession of faith, candidates receive the sacraments of initiation at the Easter vigil on Holy Saturday.

A person can excommunicate themselves or be excommunicated by committing particularly grave sins. Examples include violating the seal of confession (committed when a priest discloses the sins heard in the sacrament of Penance), persisting in heresy, creating schism, becoming an apostate or having an abortion. Throwing away or retaining for a sacrilegious purpose consecrated sacramental bread or wine received during the Eucharist is considered an excommunicable offense. Excommunication is the most severe ecclesiastical penalty because it prevents a person from validly receiving any Church sacrament. It can only be forgiven by the pope, the bishop of the diocese where the person resides, or priests authorized by him.

Catholic institutions, personnel and demographics

In 2000, worldwide Catholic institutions totalled 408,637 parishes and missions, 125,016 primary and secondary schools, 1,046 universities, 5,853 hospitals, 8,695 orphanages, 13,933 homes for the elderly and handicapped and 74,936 dispensaries, leprosaries, nurseries and other institutions. Many of these institutions are at least partially staffed by religious sisters who comprise over two thirds of all Church personnel. As of 2000, there were 769,142 religious sisters and 194,454 religious priests and brothers in Africa, the America's, Asia, Europe and Oceania. In addition, there were 3,475 bishops, 914 archbishops, 183 cardinals, 405,178 diocesan and religious priests, 27,824 permanent deacons and 110,583 diocesan and religious seminarians (men studying for the priesthood).

Church membership in 2007 exceeded 1.131 billion people; a substantial increase over the 1970 figure of 654 million. It is the largest Christian church encompassing over half of all Christians, one sixth of the world's population and is the largest organized body of any world religion, as such, it is known for its ability to use its transnational ties and organizational strength to bring significant resources to needy situations. Although the number of practicing Catholics worldwide is not reliably known, membership is growing particularly in Africa and Asia.

Some parts of Europe and the Americas have experienced a priest shortage in recent years as the number of priests has not increased in proportion to the number of Catholics.

The Latin American Church, known for its large parishes where the parishioner to priest ratio is the highest in the world, considers this to be a contributing factor in the rise of pentecostal and evangelical Christian denominations in the region. Secularism has seen a steady rise in Europe yet the Catholic presence there remains strong as evidenced by a large presence of Catholic institutions and personnel.

With an unusually high number of adult baptisms, the Church is growing faster in Africa than anywhere else even though the continent is a centre of strife between Islam and Christianity and suffers the world's highest rate of AIDS.

The Church in Asia is a significant minority among other religions yet its vibrance is evidenced by the large proportion of women religious, priests and parishes to total Catholic population.

Oceania is overwhelmingly Christian with Catholic the majority denomination. There, the Church faces challenges in reaching indigenous populations where over 715 different languages are spoken. Of the 1.5 billion worldwide Catholics, 12% reside in Africa, 50% in the American continent, 10% are in Asia, 27% in Europe and 1% live in Oceania.

Cultural influence

The cultural influence of the Catholic Church has been vast, particularly upon western society. Many historians credit the Catholic Church for the brilliance and magnificence of Western art, citing the Church's consistent opposition to Byzantine iconoclasm, the development of Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance art and the patronage of the Church for the great works of artists such as Giotto, Michelangelo, Raphael, Bernini and Leonardo da Vinci. Catholic monks developed the first forms of musical notation, and consequently an enormous body of religious music has been composed for the Catholic Church through the ages. This led directly to the emergence and development of the European tradition of classical music, and all its derivatives.

The church has been responsible for the development of several major orders of architecture. Early medieval Romanesque architecture combined massive walls, rounded arches and ceilings of masonry. To compensate for the absence of large windows, interiors were brightly painted with scenes from the Bible and the lives of the saints. Gothic architecture with its large windows and high, pointed arches, improved lighting and geometric harmony in a manner that was intended to direct the worshiper's mind to God who "orders all things". The Baroque style in art, music and architecture developed as a means of religious expression that was stirring and emotional, intended to stimulate religious fervor.

Historians of science, including non-Catholics such as J.L. Heilbron, A.C. Crombie, David Lindberg, and Thomas Goldstein, have argued that the Church had a significant, positive influence on the development of civilization. They hold that, not only did monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but that the Church promoted learning and science through its sponsorship of universities in the 11th and 12th centuries. St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church's "model theologian," not only argued that reason is in harmony with faith, he recognized that reason can contribute to understanding revelation, and so encouraged intellectual development. Catholic scientists such as Grosseteste,Copernicus and Mendel were responsible for significant advances in scientific knowledge.

History

Roman Empire

The Catholic Church believes it came fully into being on the day of Pentecost when, according to scriptural accounts, the apostles emerged from hiding following the death of Jesus to preach and spread his message. According to church tradition, the apostles traveled to northern Africa, Asia Minor, Arabia, Greece, and Rome to found the first Christian communities. Historians believe that over 40 such communities were established by the year 100. From the first century, the Church of Rome was recognized as a doctrinal authority because it was believed that the Apostles Peter and Paul had led the Church there.

The apostles had already convened the first Church council, the Council of Jerusalem, in or around the year 50 to reconcile differences concerning the Gentile mission. Although competing forms of Christianity emerged early and persisted into the fifth century, the Roman Church retained the practice of meeting in ecumenical councils to ensure that any internal doctrinal differences were quickly resolved. In the first few centuries of its existence, the Church formed its teachings and traditions into a systematic whole under the influence of theological apologists such as Pope Clement I, Ignatius of Antioch, Justin Martyr and Augustine of Hippo.

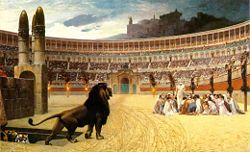

Because early Christians refused to offer sacrifices to the Roman gods or to defer to Roman rulers as gods, they were frequently subject to persecution. Beginning under Nero in the first century, peresecution, at first intermittent, became more extensive by the mid-third century, culminating in the great persecution of Diocletian and Galerius, which was seen as a final attempt to wipe out Christianity. In spite of these persecutions Christianity continued to spread. The Edict of Milan of the Emperor Constantine I finally legalized Christianity in 313.

In 325, the First Council of Nicaea was convened in response to the Arian challenge concerning the trinitarian nature of God. The council formulated the Nicene Creed as a basic statement of Christian belief. Emperor Constantine I commissioned the first Basilica of St. Peter and several other sites of lasting importance to Christianity. The observation of Sunday as the official day of worship, the use of the altar as the focal point of each church, the sign of the cross, and the liturgical calendar had been established by this time. By 380, Christianity had become the official religion of the Empire. In subsequent decades a series of ecumenical christological councils codified critical elements of the Church's theology. The Council of Rome in 382 set the Biblical canon, listing the accepted books of the Old and New Testament, and in 391 the Vulgate Latin translation of the Bible was made. The Councils of Ephesus in 431, and Chalcedon two decades later, clarified the nature of Jesus' incarnation. These definitions sparked Monophysite disagreements which led to the first of the Oriental Orthodox Churches breaking away from the Catholic Church.

Early Middle Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, the Catholic faith competed with Arian Christianity for the conversion of the barbarian tribes. The 496 conversion of Clovis I, pagan king of the Franks, marked the beginning of a steady rise of the Catholic faith in the West.

In 530, Saint Benedict wrote his monastic Rule, which became a blueprint for the organization of monasteries throughout Europe. The new monasteries preserved classical craft and artistic skills while maintaining intellectual culture within their schools, scriptoria and libraries. As well as providing a focus for spiritual life, they functioned as agricultural, economic and production centers, particularly in remote regions, becoming major conduits of civilization. From 590 Pope Gregory the Great dramatically reformed church practice and administration, launching renewed missionary efforts. As the Visigoths and Lombards moved from Arianism toward Catholicism, missionaries such as Augustine of Canterbury, Saint Boniface, Willibrord and Ansgar took Catholic Christianity to the Germanic, Irish and Slavic peoples of northern Europe. Later missions reached the Vikings and other Scandinavians.

In the early 700s, iconoclasm became a major source of conflict between the Eastern and Western churches. Under the direction of the Byzantine emperors, iconoclasts ordered the destruction of all religious images. Iconodules supported by the pope and the Western Church strongly opposed this. The dispute was resolved in 787 when the Second Council of Nicaea ruled in favour of icons. In 800, continuing disagreements with the east culminated when the pope crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor in the west. Charlemagne attempted to unify Western Europe through the common bond of Christianity, creating an improved system of education and establishing unified laws. However imperial interest created a problem for the church as succeeding emperors sought to impose increasingly tight control over the popes. Disagreements between the Eastern and Western churches arose again in 858, when Patriarch Ignatius of Constantinople, favored by the pope, was deposed for the more extreme Photios. The pope declared the election of Photios invalid and excommunicated him. The consequent long-running dispute added to the growing alienation between the churches.

After a particularly acrimonious dispute over whether Constantinople or Rome held jurisdiction over the church in Sicily, the two Churches mutually excommunicated each other in 1054, resulting in the East-West Schism. The Western (Latin) branch of Christianity has since become known as the Catholic Church, while the Eastern (Greek) branch became known as the Eastern Orthodox Church. The Second Council of Lyon (1274) and the Council of Florence (1439) both failed to heal the schism. Some Eastern churches have subsequently reunited with the Catholic Church. Officially, the two churches remain in schism, although excommunications were mutually lifted in 1965.

High Middle Ages

The Cluniac reform of monasteries that had begun in 910 sparked a great monastic renewal. Monasteries introduced new crops, developed technologies such as metallurgy, and fostered the creation and preservation of literature. They could also function as credit establishments promoting economic growth. Monasteries, convents and cathedrals still operated virtually all schools and libraries. After 1100, some cathedral schools split into lower, grammar, schools and higher schools for advanced learning. First in Bologna, then at Paris and Oxford, some of these higher schools developed into universities, the direct ancestors of the modern Western institutions. Notable theologians such as Thomas Aquinas worked to explain the connection between human experience and faith. His Summa Theologica was a key intellectual achievement in its synthesis of Aristotelian thought and Christianity.

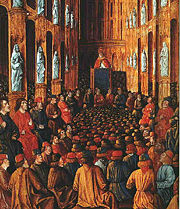

In 1095, Byzantine emperor Alexius I appealed to Pope Urban II for help in warding off a Turkish invasion. Urban launched a military campaign known as the First Crusade, believing that it might help to bring about reconciliation with Eastern Christianity. Fueled by reports of Muslim atrocities against Christians, the series of military campaigns that followed were intended to return the Holy Land to Christian control. The goal was not permanently realized, and episodes of brutality committed by the armies of both sides left a legacy of mutual distrust between Muslims and Western and Eastern Christians. The sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade left Eastern Christians embittered, despite the fact that Pope Innocent III had expressly forbidden any such attack. In 2001, Pope John Paul II apologized to the Orthodox Christians for the sins of Catholics including the sacking of Constantinople in 1204.

Cistercian monk Bernard of Clairvaux exerted great influence over the eight new monastic orders founded in the 12th century, including the Military Knights of the Crusades. His influence led Pope Alexander III to begin reforms that would lead to the establishment of canon law. In the following century, new mendicant orders were founded by Francis of Assisi and Dominic de Guzmán which brought consecrated religious life into urban settings.

In the 12th century, members of the Dominican order attempted to convert the Cathars, a powerful heretical movement centered in southern France. Cathars held a dualistic belief in extreme asceticism, taught that all matter was evil, accepted suicide and denied the value of Church sacraments. After a papal legate was murdered by them in 1208, Pope Innocent III declared the Albigensian Crusade. Concern that matters had grown so out of hand prompted Innocent III to informally institute the first papal inquisition to to bring people considered heretics to trial. Formalized under Gregory IX, this Medieval inquisition executed an average of three people per year for heresy at its height. King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella formed an inquisition in 1480, originally to deal with distrusted ex-Jewish and ex-Muslim converts. Over a 350-year period, this Spanish Inquisition executed between 3,000 and 4,000 people, representing around two percent of those accused. In 1482, Pope Sixtus IV condemned its excesses but Ferdinand ignored his protests. Despite their severities many historians consider that for centuries popular literature and Protestant propaganda have exaggerated the horrors of these inquisitions. Over all, one percent of those tried by the inquisitions received death penalties, leading many scholars to consider them rather lenient when compared to the secular courts of the period.

A growing sense of church-state conflicts marked the 14th century. Clement V in 1309 became the first of seven popes to reside under French influence in the fortified city of Avignon. What became known as the Avignon Papacy ended in 1378 when, at the urging of Catherine of Siena and others, the papacy finally returned to Rome. With the death of Pope Gregory XI later that year, the papal election was strongly disputed. Supporters of Italian and French-backed candidates were unable to come to agreement, resulting in the Western schism in which for 38 years, separate claimants to the papal throne sat in Rome and Avignon. Efforts at resolution further complicated the issue when a third, compromise, pope was elected in 1409. The matter was finally resolved in 1417 at the Council of Constance where the cardinals called upon all three claimants to the papal throne to resign, and held a new election naming Martin V pope.

Late Medieval and Renaissance

In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, European explorers and missionaries spread Catholicism to the Americas, Asia, Africa and Oceania. Pope Alexander VI, had awarded colonial rights over most of the newly discovered lands to Spain and Portugal. Under the patronato system, however, state authorities, not the Vatican, controlled all clerical appointments. In December 1511, Antonio de Montesinos, a Dominican friar, openly rebuked the Spanish rulers of Hispaniola for their mistreatment of the American natives, telling them "... you are in mortal sin ... for the cruelty and tyranny you use in dealing with these innocent people". King Ferdinand enacted the Laws of Burgos and Valladolid in response. However enforcement was lax, and while some blame the Church for not doing enough to liberate the Indians, others point to the Church as the only voice raised on behalf of indigenous peoples. The issue resulted in a crisis of conscience in 16th-century Spain. The reaction of Catholic theologians, such as Bartolome de Las Casas and Francisco de Vitoria, led to debate on the nature of human rights and the birth of modern international law.

In 1521 Spanish explorer Ferdinand Magellan made the first Catholic converts in the Philippines. The following year, the first Franciscan missionaries arrived in Mexico, establishing schools, model farms and hospitals. When some Europeans questioned whether the Indians were truly human and worthy of baptism, Pope Paul III in the 1537 bull Sublimis Deus confirmed that "the souls of the Indians were as immortal as those of Europeans". Over the next 150 years, missions expanded into southwestern North America. Native people were often legally defined as children, and priests took on a paternalistic role, sometimes enforced with corporal punishment. Elsewhere, Portuguese missionaries under the Spanish Jesuit Francis Xavier evangelized in India and Japan. By the end of the 16th century tens of thousands of Japanese followed Roman Catholicism. Church growth came to a halt in 1597 under the Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu who, in an effort to isolate the country from foreign influences, launched a severe persecution of Christians. Despite enforced isolation, a minority Christian population survived into the 19th century.

In Europe, the Renaissance marked a period of renewed interest in ancient and classical learning. It also brought a re-examination of accepted beliefs. Cathedrals and churches had long served as picture books and art galleries for millions of the uneducated. The stained glass windows, frescoes, statues and paintings retold the stories of the saints and of biblical characters. The Church sponsored great Renaissance artists like Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. In 1509, however, the most famous scholar of the age, Erasmus, wrote The Praise of Folly, a work which captured a widely held unease about corruption in the Church. In this period, powerful and worldly men like Roderigo Borgia, ( Pope Alexander VI) had been able to win election to the papacy. Simony, nepotism, clerical wealth and hypocrisy all contributed to a general feeling among educated people that reform of some sort was necessary. In 1517, Martin Luther included his Ninety-Five Theses in a letter to several bishops. His theses protested key points of Catholic doctrine as well as the sale of indulgences. Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin, and others further criticized Catholic teachings. These challenges developed into the Protestant Reformation. In Germany, the reformation led to a nine-year war between the Protestant Schmalkaldic League and the Catholic Emperor Charles V. In 1618 a far graver conflict, the Thirty Years' War, followed. In France, a series of conflicts termed the French Wars of Religion were fought from 1562 to 1598 between the Huguenots and the forces of the French Catholic League. King Henry IV's 1598 Edict of Nantes, which granted civil and religious toleration to Protestants was hesitantly accepted by Pope Clement VIII.

The English Reformation was ostensibly based on Henry VIII's desire for annulment of his marriage with Catherine of Aragon. The Acts of Supremacy made the English monarch head of the new Church of England. Beginning in 1536, some 825 monasteries throughout England, Wales and Ireland were dissolved and Catholic churches were confiscated. Henry VIII executed those like Thomas More who opposed him, but reaffirmed Catholic doctrines such as transubstantiation and the celibacy of the clergy in the Six Articles of 1539. This affirmation did not extend to papal authority or the dissolution of monasteries, and when he died in 1547 all monasteries, convents and shrines were gone. Mary I of England reunited the Church of England with Rome and, against much advice, persecuted Protestants. The following monarch, Elizabeth I re-imposed the Act of Supremacy, preventing Catholics from becoming members of professions, holding public office, voting or educating their children. Executions of Catholics under Elizabeth I eventually surpassed those of the Marian persecutions and persisted under subsequent English monarchs. Penal laws were also enacted in Ireland.

The Catholic Church responded to doctrinal challenges and abuses highlighted by the Reformation at the Council of Trent (1545–1563), which became the driving-force of the Counter-Reformation. Doctrinally, it reaffirmed central Catholic doctrines such as transubstantiation, and the requirement for love and hope as well as faith to attain salvation. It also made important structural reforms, most importantly by improving the education of the clergy and laity, and consolidating the central jurisdiction of the Roman Curia. New religious orders were founded, including the Theatines, Barnabites and Jesuits some of which became the great missionary orders of later years. The writings of figures such as Teresa of Avila, Francis de Sales and Philip Neri spawned new schools of spirituality within the Church. To popularize Counter-Reformation teachings, the Church encouraged the Baroque style in art, music and architecture. Baroque religious expression was deliberately stirring and emotional, intended to stimulate religious fervor.

In 1582 Pope Gregory XII introduced the Gregorian Calendar to replace the increasingly inaccurate Julian Calendar, however the reform was resisted for centuries in many protestant countries.

Enlightenment

Toward the latter part of the 17th century, Pope Innocent XI attempted to reform abuses by the Church, including simony, nepotism and the lavish papal expenditures that had caused him to inherit a papal debt of 50,000,000 scudi. He promoted missionary activity across the world, tried to unite Europe against Turkish invasion, and condemned religious persecution of all kinds. In 1685 King Louis XIV of France issued the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, ending a century-long experiment in religious toleration. However, the religious conflicts of the Reformation era had provoked a backlash against Christianity. Secular powers gained control of virtually all major Church appointments as well as many of the Church's properties. In France, Louis XIV endorsed Gallicanism as a means to weaken and control the church. Jansenism and the attacks of thinkers such as Denis Diderot challenged fundamental doctrines of the Church. Matters grew still worse with the violent anti-clericalism of the French Revolution. When large numbers of priests refused to take an oath of obedience to the National Assembly, the Church was outlawed, to be replaced by a new religion of the worship of "Reason". All monasteries were shut down or destroyed, 30,000 priests were exiled and hundreds more were killed.

Pope Pius VI joined the First Coalition against the revolutionaries, but was imprisoned by French troops when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Italy, dying in 1799 after six weeks of captivity. To win popular support for his rule, however, Napoleon re-established the Catholic Church in France through the Concordat of 1801. All over Europe, the end of the Napoleonic wars brought Catholic revival, renewed enthusiasm, and new respect for the papacy following the depredations of the previous era.

In the Americas, Franciscan priest Junípero Serra founded a series of new missions in cooperation with the Spanish government and military. These missions brought grain, cattle and a new way of living to the Indian tribes of California. San Francisco was founded in 1776 and Los Angeles in 1781. However, in bringing Western civilization to the area, the missions have been held responsible for the loss of nearly a third of the native population, primarily through disease.

In South America, Jesuits missionaries protected native peoples from enslavement by establishing semi-independent settlements called reductions. Pope Gregory XVI, challenging Spanish and Portuguese sovereignty, appointed his own candidates as bishops in the colonies, condemned slavery and the slave trade in 1839 (papal bull In Supremo Apostolatus), and approved the ordination of native clergy in spite of government racism.

In China, however, the Chinese Rites controversy led the Kangxi Emperor to outlaw Christian missions in 1721. This controversy added fuel to growing criticism of the Jesuits who were seen to symbolize the independent power of the Church, and in 1773, European rulers united to force Pope Clement XIV to dissolve the order. The Jesuits were eventually restored in the 1814 papal bull Sollicitudo omnium ecclesiarum.

Industrial age

In Latin America, anti-clerical regimes came to power from the 1830s onward. One such regime emerged in Mexico in 1860. Church properties were confiscated and basic civil and political rights were denied to religious orders and the clergy. Harsh enforcement of these measures in later decades led to an uprising known as the Cristero War. Between 1926 and 1934, over 3,000 priests were exiled or assassinated. Despite persecution, the Church in Mexico continued to grow, and a 2000 census reported that 88 percent of Mexicans identify as Catholic. In 1954, under General Juan Perón, Argentina saw destruction of churches, denunciations of clergy and confiscation of Catholic schools.

In 1870, the First Vatican Council affirmed the doctrine of papal infallibility when exercised in specifically defined pronouncements. Controversy over this and other issues resulted in a small breakaway movement called the Old Catholic Church.

The Industrial Revolution brought growing concern about the deteriorating working and living conditions of urban workers. In 1891, influenced by the German Catholic industrialist Lucien Harmel, Pope Leo XIII published the encyclical Rerum Novarum. This set out Catholic social teaching in terms that rejected socialism but advocated the regulation of working conditions, the establishment of a living wage and the right of workers to form trade unions.

By the close of the 19th century European powers had gained control of most of the African contintent, introducing massive change. Catholic missionaries followed colonial governments into Africa, building schools, monasteries and churches.

In the 1937 encyclical Mit brennender Sorge, drafted by the future Pope Pius XII, Pope Pius XI warned Catholics that antisemitism is incompatible with Christianity. After World War II historians such as David Kertzer accused the Church of encouraging centuries of anti–semitism, and Pope Pius XII of not doing enough to stop Nazi atrocities. Prominent members of the Jewish community, including Golda Meir, Albert Einstein, Moshe Sharett and Rabbi Isaac Herzog contradicted the criticisms and spoke highly of Pius' efforts to protect Jews, while others such as rabbi David G. Dalin noted that "hundreds of thousands" of Jews were saved by the Church. Even so, Pope John Paul II acknowledged past sins of the Church against Jews, and in 2000 formally apologized to the Jewish people by inserting a prayer at Jerusalem's Western Wall."

In the aftermath of World War II communist governments in Eastern Europe severely restricted religious freedoms. The Church's resistance and the leadership of Pope John Paul II have been credited with hastening the downfall of communist governments across Europe in 1991, even though some priests collaborated with the regime.

Vatican II

The Catholic Church engaged in a comprehensive process of reform following the Second Vatican Council (1962–65). Intended as a continuation of Vatican I, under Pope John XXIII the council developed into an engine of modernisation. As well as making pronouncements on religious freedom, the nature of the church and the mission of the laity and, the council approved a revision of formal worship, permitting the Latin liturgical rites to use vernacular languages as well as Latin during mass and other sacraments. Christian unity became a greater priority. In addition to finding more common ground with Protestant churches, the Catholic Church has discussed the possibility of unity with the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Changes to old rites and ceremonies following Vatican II stunned many Catholics and produced a variety of responses. Some stopped going to church, while others tried to preserve the old liturgy with the help of sympathetic priests. The latter formed the basis of today's Traditionalist Catholic groups, which believe that the reforms of Vatican II have gone too far in departing from traditional church norms. According to Professor Thomas Bokenkotter, however, most catholics "accepted the changes more or less gracefully but with little enthusiasm and have learned to take in stride the continuing series of changes that have modified not only the Mass but the other sacraments as well." Liberal Catholics form another dissenting group. They typically take a less literal view of the Bible and of divine revelation, and sometimes disagree with official Church views on social and political issues. The most famous liberal theologian of recent times has been Hans Küng, whose unorthodox views of the incarnation, and his denials of infallibility led to Church withdrawal of his authorization to teach as a Catholic in 1979.

In the 1960s, growing social awareness and politicization in the Latin American Church gave birth to liberation theology. Peruvian priest, Gustavo Gutiérrez, became one of the movement's most influential scholars. The 1979 bishops' conference in Mexico officially declared the Latin American Church's "preferential option for the poor". Salvadoran Archbishop Óscar Romero became the region's most famous contemporary martyr in 1980, when he was murdered while saying mass by forces allied with the government. Both Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI (as Cardinal Ratzinger) denounced the movement. The Brazilian theologian Leonardo Boff was twice ordered to cease publishing and teaching. While Pope John Paul II was criticized for his severity in dealing with proponents of the movement, he maintained that the Church, in its efforts to champion the poor, should not do so by resorting to violence or partisan politics. The movement is still alive in Latin America today, though the Church now faces the challenge of Pentecostal revival in much of the region.

The sexual revolution of the 1960s brought challenging issues for the Church. Pope Paul VI's 1968 encyclical Humanae Vitae affirmed the sanctity of life from conception to natural death, rejected the use of contraception, and declared both abortion and euthanasia to be murder. The Church's rejection of the use of condoms has provoked criticism, especially with respect to countries where AIDS and HIV have attained epidemic proportions. The Church maintains that countries like Kenya, where behavioural changes are endorsed instead of condom use, have experienced greater progress towards controlling the disease than countries solely promoting condoms. Efforts to lead the Church to consider the ordination of women led Pope John Paul II to issue the 1988 encyclical Mulieris Dignitatem that declared that women had a different, yet equally important role in the Church. In 1994 the encyclical Ordinatio Sacerdotalis further explained that the Church follows the example of Jesus, who chose only men for the specific priestly duty. In 1995 Pope John Paul II stated that the death penalty was appropriate only when it was the only way to defend society, and the modern penal system made this option rare or nonexistent.

Several major lawsuits emerged in 2001 claiming that priests had sexually abused minors. Some priests resigned, others were defrocked and jailed and financial settlements were agreed with many victims. In the US, where the vast majority of sex abuse cases occurred, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops commissioned a comprehensive study that found that four percent of all priests who served in the US from 1950 to 2002 faced some sort of sexual accusation. The Church was widely criticized when it emerged that some bishops had known about abuse allegations, and reassigned many of the accused after first sending them to psychiatric counseling. Some bishops and psychiatrists contended that the prevailing psychology of the times suggested that people could be cured of such behaviour through counseling. Pope John Paul II responded by declaring that "there is no place in the priesthood and religious life for those who would harm the young". The US Church instituted reforms to prevent future abuse by requiring background checks for Church employees; and, because the vast majority of victims were teenage boys, the worldwide Church also prohibited the ordination of men with "deep–seated homosexual tendencies". It now requires dioceses faced with an allegation to alert the authorities, conduct an investigation and remove the accused from duty. In 2008, Cardinal Cláudio Hummes, head of the Vatican Congregation for the Clergy, affirmed that the scandal was an "exceptionally serious" problem, but estimated that it was "probably caused by 'no more than 1 per cent'" of the over 400,000 Catholic priests worldwide. Some commentators, such as journalist Jon Dougherty, have argued that media coverage of the issue has been excessive, given that the same problems plague other institutions such as the US public school system with much greater frequency.

Catholicism today

With the election of Pope Benedict XVI in 2005, the Church saw largely a continuation of the policies of his predecessor, John Paul II, with some notable exceptions. Benedict lowered the barriers for laicization, reverted the decision of his predecessor regarding papal elections, and decentralized beatification. His first encyclical Deus Caritas Est (God is Love) discussed love and sex without mentioning the continued opposition of the Catholic Church to several views on sexuality. In an address at the University of Regensburg, Germany, Benedict maintained that in the Western world, to a large degree, only positivistic reason and philosophy are valid. Yet the world's profoundly religious cultures see this exclusion of the divine, as an attack on their most profound convictions. A concept of reason which excludes the divine, is incapable of entering into the dialogue of cultures, according to Benedict. During this Regensburg address Benedict quoted a Byzantine emperor who said Muhammad had brought the world only things "evil and inhuman". After the Pope explained his quote, the dialogue continued, with cordial meetings of Islam representatives in Turkey, and the ambassadors of Muslim countries in 2007. A May 2008 declaration agreed on between Benedict and Muslims, led by Mahdi Mostafavi stressed, that religion is essentially non-violent and that violence can be justified neither by reason nor by faith. Pope Benedict has spoken out against human rights abuses in China, Darfur, and Iraq and encouraged protection of the environment and the poor. He spoke strongly against drug dealers in Latin America, against abuse scandals, and Catholic politicians supporting legalized abortion.

In 2007, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith clarified the Catholic Church's position vis-a-vis other Christian communities. Quoting the statement of Pope Paul VI: "What the Church has taught down through the centuries, we also teach: that there is only one Church", the Vatican insisted that while communities separated from the Catholic Church can be instruments of salvation, only those with apostolic succession can be properly termed "churches". Some Protestants representatives were not surprised, others announced themselves insulted by the document, which also stressed the Church's commitment to ecumenical dialogue. A Church official told Vatican radio that any dialogue is facilitated when parties are clear about their identity. Important ethical decisions during the pontificate of Benedict XVI involved continued nutrition and hydration for persons in a vegetative status. While making many exceptions, the Church ruled that "the provision of water and food, even by artificial means, always represents a natural means for preserving life."