Napoleon I of France

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Historical figures

| Napoleon I | |

| Emperor of the French, King of Italy Mediator of the Swiss Confederation Protector of the Confederation of the Rhine |

|

Napoleon in His Study by Jacques-Louis David (1812) |

|

| Reign | 20 March 1804– 6 April 1814 1 March 1815– 22 June 1815 |

|---|---|

| Coronation | 2 December 1804 |

| Full name | Napoleon Bonaparte |

| Born | 15 August 1769 |

| Birthplace | Ajaccio, Corsica |

| Died | 5 May 1821 (aged 51) |

| Place of death | Longwood, St. Helena |

| Buried | Les Invalides, Paris |

| Predecessor | French Consulate (as Executive Power of the French First Republic, with himself as First Consul); Previous ruling Monarch : Louis XVI as King of the French (died 1793) |

| Successor | Louis XVIII ( de facto) Napoleon II ( de jure) |

| Consort | Josephine de Beauharnais Marie Louise of Austria |

| Offspring | Napoleon II |

| Royal House | Bonaparte |

| Father | Carlo Buonaparte |

| Mother | Letizia Ramolino |

Napoleon I (born Napoleone di Buonaparte, later Napoleon Bonaparte) ( 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821) was a French military and political leader who had a significant impact on modern European history. He was a general during the French Revolution, the ruler of France as First Consul of the French Republic, Emperor of the French, King of Italy, Mediator of the Swiss Confederation and Protector of the Confederation of the Rhine.

Born in Corsica and trained in mainland France as an artillery officer, he rose to prominence as a general of the French Revolution, leading successful campaigns against the First and Second Coalitions arrayed against France. In 1799, Napoleon staged a coup d'état and installed himself as First Consul; five years later he crowned himself Emperor of the French. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, he turned the armies of France against almost every major European power, dominating continental Europe through a lengthy streak of military victories—epitomized through battles such as Austerlitz and Friedland—and the formation of extensive alliance systems, appointing close friends and family members as monarchs and government figures of French-dominated states.

The disastrous French invasion of Russia in 1812 marked a turning point in Napoleon's fortunes. The campaign wrecked the Grande Armée, which never regained its previous strength. In 1813, the Sixth Coalition defeated his forces at Leipzig and invaded France, forcing him to abdicate in April 1814 and exiling him to the island of Elba. Less than a year later, he returned to France, regaining control of the government in the Hundred Days prior to his final defeat at Waterloo in June 1815. Napoleon spent the last six years of his life under British supervision on the island of Saint Helena.

Napoleon developed relatively few military innovations himself, drawing his tactics from a variety of sources and scoring major victories with a modernized French army. His campaigns are studied at military academies all over the world and he is widely regarded as one of history's greatest commanders. Whilst considered a tyrant by his opponents, he is also remembered for establishing the Napoleonic code, which laid the bureaucratic foundations for the modern French state.

Origins and education

Napoleon was born in the town of Ajaccio on Corsica, on 15 August 1769, one year after the island was transferred to France by the Republic of Genoa. He was named Napoleone di Buonaparte (in Corsican, Nabolione or Nabulione), though he later adopted the more French-sounding Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon wrote to Pasquale di Paoli - leader of a Corsican revolt against the French - in 1789: "I was born when my country was dying. Thirty thousand French, vomited on our shores, drowning the throne of liberty in waves of blood- such was the horrid sight which first met my view." His heritage earned him popularity among Italians during his Italian campaigns.

The family were minor Italian nobility coming from Lombard stock and Lunigiana origin. The family had moved to Florence and broke into two branches; the original branch, Buonaparte-Sarzana, were compelled to leave Florence after the defeat of the Ghibellines and came to Corsica in the 16th century, when the island was still a possession of Genoa.

His father Carlo Buonaparte, an attorney, was named Corsica's representative to the court of Louis XVI in 1778, where he remained for a number of years. The dominant influence of Napoleon's childhood was his mother, Maria Letizia Ramolino. Her firm discipline helped restrain the petulant Napoleon.

Napoleon had an elder brother, Joseph, and younger siblings Lucien, Elisa, Louis, Pauline, Caroline and Jérôme. He was baptised Catholic just before his second birthday, on 21 July 1771 at Ajaccio Cathedral.

Napoleon's noble, moderately affluent background and family connections afforded him greater opportunities to study than were available to a typical Corsican of the time. On 15 May 1779, at age nine, Napoleon was admitted to a French military school at Brienne-le-Château, a small town near Troyes. He had to learn French before entering the school, but he spoke with a marked Italian accent throughout his life and never learned to spell properly. During these school years Napoleon was teased by other students for his Corsican accent and he buried himself in study. Upon completing the school in 1784, Bonaparte was admitted to the elite École Royale Militaire (Military college) in Paris. Though he had initially sought a naval assignment, he studied artillery and completed the two-year course of study in one year. An examiner judged him as "very applied [to] abstract sciences, little curious as to the others; a thorough knowledge of mathematics and geography."

Early career

Upon graduation in September 1785, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in La Fère artillery regiment and took up his new duties in January 1786 at the age of 16. Napoleon served on garrison duty in Valence and Auxonne until after the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789 - though he took nearly two years of leave in Corsica and Paris during this period. He spent most of the next several years in Corsica, where a complex three-way struggle was playing out between royalists, revolutionaries, and Corsican nationalists. Bonaparte supported the Jacobin faction and gained the rank of lieutenant-colonel of a regiment of volunteers. After coming into conflict with the increasingly conservative nationalist leader, Pasquale Paoli, Bonaparte and his family fled to the French mainland in June 1793.

Through the help of fellow Corsican Saliceti, Napoleon was appointed artillery commander of the French forces besieging Toulon, which had risen in revolt against the republican government and was occupied by British troops. He spotted an ideal place for French guns to be set up so they could dominate the city's harbour, and the British ships would be forced to evacuate. The assault on the position, during which Bonaparte was wounded in the thigh, led to the recapture of the city and his promotion to Brigadier General. His actions brought him to the attention of the Committee of Public Safety, and he became a close associate of Augustin Robespierre, younger brother of the Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre. Following the fall of the elder Robespierre he was briefly imprisoned in the Chateau d'Antibes on 6 August 1794, but was released within two weeks. He also became engaged to Désirée Clary, later Queen of Sweden and Norway, but the engagement was broken off by Napoleon in 1796.

13 Vendemiaire

Bonaparte was serving in Paris when royalists and counter-revolutionaries organised an armed protest against the National Convention on 3 October 1795. Bonaparte was given command of the improvised forces defending the Convention in the Tuileries Palace. He seized artillery pieces with the aid of a young cavalry officer, Joachim Murat - who later became his brother-in-law - and used it the next day to repel the attackers, of which 300 died and the rest fled. This triumph earned him sudden fame, wealth, and the patronage of the new Directory, particularly that of its leader, Barras. Within weeks he was romantically attached to Barras's former mistress, Josephine de Beauharnais, whom he married on 9 March 1796.

First Italian campaign

Days after his marriage, Bonaparte took command of the French " Army of Italy" on 27 March 1796, leading it on a successful invasion of Italy. At the battles of Montenotte and Lodi, he defeated Austrian forces, then drove them out of Lombardy and defeated the army of the Papal States. Pope Pius VI had protested at the execution of Louis XVI, so France retaliated by annexing two small papal territories.

Bonaparte ignored the Directory's order to march on Rome and dethrone the Pope. It was not until the following year that General Berthier captured Rome and took Pius VI prisoner on 20 February. The Pope died of illness while in captivity. In early 1797, Bonaparte led his army into Austria and forced it to sue for peace. The resulting Treaty of Campo Formio gave France control of most of northern Italy, along with the Low Countries and Rhineland, but a secret clause promised Venice to Austria. Bonaparte then marched on Venice and forced its surrender, ending more than 1,000 years of independence. Later in 1797, Bonaparte organised many of the French-dominated territories in Italy into the Cisalpine Republic.

His series of military triumphs was a result of his ability to apply his knowledge of conventional military thought to real-world situations, as demonstrated by his creative use of artillery tactics, using it as a mobile force to support his infantry. As he described it: "...Although I have fought sixty battles, I have learned nothing which I did not know at the beginning. Look at Caesar; he fought the first like the last." Contemporary paintings of his headquarters during the Italian campaign depict his use of the Chappe semaphore line, first implemented in 1792. He was also adept at both intelligence and deception and had a sense of when to strike. He often won battles by concentrating his forces on an unsuspecting enemy, by using spies to gather information about opposing forces, and by concealing his own troop deployments. In this campaign, often considered his greatest, Napoleon's army captured 160,000 prisoners, 2,000 cannons, and 170 standards. A year of campaigning had witnessed breaks with the traditional norms of 18th century warfare and marked a new era in military history.

While campaigning in Italy, General Bonaparte became increasingly influential in French politics. He published two newspapers, ostensibly for the troops in his army, but widely circulated within France as well. In May 1797 he founded a third newspaper, published in Paris, Le Journal de Bonaparte et des hommes vertueux. Elections in mid-1797 gave the royalist party increased power, alarming Barras and his allies on the Directory. The royalists, in turn, began attacking Bonaparte for looting Italy and overstepping his authority in dealings with the Austrians. Bonaparte sent General Augereau to Paris to lead a coup d'etat and purge the royalists on 4 September ( 18 Fructidor). This left Barras and his Republican allies in firm control again, but dependent on Bonaparte to maintain it. Bonaparte himself proceeded to the peace negotiations with Austria, then returned to Paris in December as the conquering hero and the dominant force in government, more popular than the Directors.

Egyptian expedition

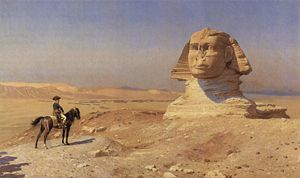

In March 1798, Bonaparte proposed a military expedition to seize Egypt, then a province of the Ottoman Empire, seeking to protect French trade interests and undermine Britain's access to India. The Directory, though troubled by the scope and cost of the enterprise, readily agreed so the popular general would be away from the centre of power.

In May, Bonaparte was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences. His Egyptian expedition included a group of 167 scientists: mathematicians, naturalists, chemists and geodesers among them; their discoveries included the Rosetta Stone and their work was published in the Description of Egypt in 1809. This deployment of intellectual resources is considered by Ahmed Youssef an indication of Bonaparte's devotion to the principles of the Enlightenment, and by Juan Cole as a masterstroke of propaganda, obfuscating the true imperialist motives of the invasion. In a largely unsuccessful effort to gain the support of the Egyptian populace, Bonaparte also issued proclamations casting himself as a liberator of the people from Ottoman oppression, and praising the precepts of Islam.

Bonaparte's expedition seized Malta from the Knights of Saint John on 9 June and then landed successfully at Alexandria on 1 July, temporarily eluding pursuit by the British Royal Navy. After landing he successfully fought The Battle of Chobrakit against the Mamelukes, an old power in the Middle East. This battle helped the French plan their attack in the Battle of the Pyramids fought over a week later, about 6 km from the pyramids. Bonaparte's forces were greatly outnumbered by the Mamelukes cavalry - 20,000 against 60,000 - but Bonaparte formed hollow squares, keeping supplies safely on the inside. In all, 300 French and approximately 6,000 Egyptians were killed.

While the battle on land was a resounding French victory, the British Royal Navy managed to win at sea. The ships that had landed Bonaparte and his army sailed back to France, while a fleet of ships of the line remained to support the army along the coast. On 1 August the British fleet under Horatio Nelson fought the French in the Battle of the Nile, capturing or destroying all but two French vessels. With Bonaparte land-bound, his goal of strengthening the French position in the Mediterranean Sea was frustrated, but his army succeeded in consolidating power in Egypt, though it faced repeated uprisings.

In early 1799, he led the army into the Ottoman province of Damascus (Syria and northern Israel) and defeated numerically superior Ottoman forces in several battles, but his army was weakened by disease—mostly bubonic plague—and poor supplies. Napoleon led 13,000 French soldiers to the conquest of the coastal towns of El Arish, Gaza, Jaffa, and Haifa.

The storming of Jaffa was particularly brutal. Though the French took control of the city within a few hours of the attack beginning, the French soldiers bayoneted approximately 2,000 Turkish soldiers trying to surrender. The soldiers' then turned on the inhabitants of the town. Men, women, and children were robbed and murdered for three days, and the massacre ended with even more bloodshed, as Napoleon ordered 3,000 Turkish prisoners executed.

Napoleon was unable to reduce the fortress of Acre, after his army was weakened by the plague, and returned to Egypt in May. To speed up the retreat, Bonaparte took the controversial step of ordering the poisoning of plague-stricken men along the way; it is not clear how many died. His supporters have argued this decision was necessary given the continuing harassment of stragglers by Ottoman forces. Back in Egypt, on 25 July, Bonaparte defeated an Ottoman amphibious invasion at Abukir.

With the Egyptian campaign stagnating, and political instability developing back home, Bonaparte left Egypt for France in August, 1799, leaving his army under General Kléber.

Ruler of France

Coup d'état of 18 Brumaire

Whilst in Egypt, Bonaparte stayed informed of European affairs by relying on the irregular delivery of newspapers and dispatches. On 24 August 1799, he set sail for France, taking advantage of the temporary departure of British ships blockading French coastal ports. The Directory had already ordered his and the army's return, as France had suffered a series of military defeats to Second Coalition forces, and a possible invasion of French territory loomed. He did not receive these orders due to poor lines of communication and on his return the Directory discussed his 'desertion' though they did not discipline him.

By the time he reached Paris in October, a series of French victories meant an improvement in the previously precarious military situation and discussion of his 'desertion' was brushed aside. The Republic was bankrupt, however, and the corrupt and inefficient Directory was more unpopular than ever with the public.

Bonaparte was approached by one of the Directors, Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, seeking his support for a coup d'état to overthrow the constitutional government. The plot included Bonaparte's brother Lucien, then serving as speaker of the Council of Five Hundred, Roger Ducos, another Director, and Talleyrand. On 9 November - 18 Brumaire - Bonaparte was charged with the safety of the legislative councils and the following day, he led troops to seize control and disperse them, leaving a legislative rump to name Bonaparte, Sieyès, and Ducos as provisional Consuls to administer the government. Though Sieyès expected to dominate the new regime, he was outmaneuvered by Bonaparte, who drafted the Constitution of the Year VIII and secured his own election as First Consul. This made Bonaparte the most powerful person in France, powers that were increased by the Constitution of the Year X, which declared him First Consul for life.

Bonaparte instituted several lasting reforms, including centralized administration of the departements, higher education, a tax system, a central bank, law codes, and road and sewer systems. He negotiated the Concordat of 1801 with the Catholic Church, seeking to reconcile the mostly Catholic population with his regime. It was presented alongside the Organic Articles, which regulated public worship in France. His set of civil laws, the Napoleonic Code or Civil Code, has importance to this day in modern continental Europe, Latin America and the US, specifically Louisiana.

The Code was prepared by committees of legal experts under the supervision of Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès, who held the office Second Consul from 1799 to 1804; Bonaparte participated actively in the sessions of the Council of State that revised the drafts. Other codes were commissioned by Bonaparte to codify criminal and commerce law. In 1808, a Code of Criminal Instruction was published, which enacted precise rules of judicial procedure. Though by today's standards the code excessively favours the prosecution, when enacted it sought to protect personal freedoms and to remedy the prosecutorial abuses commonplace in contemporary European courts.

Second Italian campaign

In 1800, Bonaparte returned to Italy, which the Austrians had reconquered during his absence in Egypt. He and his troops crossed the Alps in spring - he rode a mule, not the white charger on which David famously depicted him.

While the campaign began badly, Napoleon's forces eventually routed the Austrians in June at the Battle of Marengo, leading to an armistice. Napoleon's brother Joseph, who was leading the peace negotiations in Lunéville, reported that due to British backing for Austria, Austria would not recognise France's newly gained territory. As negotiations became more and more fractious, Bonaparte gave orders to his general Moreau to strike Austria once more. Moreau led France to victory at Hohenlinden. As a result, the Treaty of Lunéville was signed in February 1801: the French gains of the Treaty of Campo Formio were reaffirmed and increased. Later that year, Bonaparte became President of the French Academy of Sciences and appointed Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre its Permanent Secretary. He also re-established slavery in France; it had been banned following the revolution.

Interlude of peace

The British signed the Treaty of Amiens in March 1802, setting the terms for peace, which included the withdrawal of British troops from several colonial territories recently occupied. The peace between France and Britain was uneasy and short-lived. The monarchies of Europe were reluctant to recognise a republic, fearing the ideas of the revolution might be exported to them. In Britain, the brother of Louis XVI was welcomed as a state guest although officially Britain recognised France as a republic. Britain failed to evacuate Malta, as promised, and protested against France's annexation of Piedmont, and Napoleon's Act of Mediation in Switzerland, though neither of these areas were covered by the Treaty.

In 1803 Bonaparte faced a major setback and eventual defeat in the Haitian Revolution, when an army he sent to reconquer Saint-Domingue and establish a base following a slave revolt, was destroyed by a combination of yellow fever and fierce resistance led by Haitian Generals Toussaint L'Ouverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines. Facing imminent war with Britain and bankruptcy, he recognised French possessions on the mainland of North America would be indefensible and sold them to the United States—the Louisiana Purchase—for less than three cents per acre ($7.40 per sq km). The dispute over Malta ended with Britain declaring war on France in 1803 to support French royalists.

Coronation as Emperor

In January 1804, Bonaparte's police uncovered an assassination plot against him, ostensibly sponsored by the Bourbons. In retaliation, Bonaparte ordered the arrest of the Duc d'Enghien, in a violation of the sovereignty of Baden. After a hurried secret trial, the Duke was executed on 21 March. Bonaparte used this incident to justify the re-creation of a hereditary monarchy in France, with himself as Emperor, on the theory that a Bourbon restoration would be impossible once the Bonapartist succession was entrenched in the constitution.

Napoleon crowned himself Emperor on 2 December 1804 at Notre Dame de Paris he then crowned his wife Josephine Empress. At Milan's cathedral on 26 May 1805, Napoleon was crowned King of Italy with the Iron Crown of Lombardy.

In May 1809, Napoleon declared the Pontifical States annexed to the empire and Pius VII responded by excommunicating him. Though Napoleon did not instruct his officers to kidnap the Pope, once Pius was a prisoner, Napoleon did not offer his release. The Pope was moved throughout Napoleon's territories, sometimes whilst ill, and Napoleon sent delegations to pressure him into issues including giving-up power and signing a new concordat with France. The Pope remained confined for 5 years, and did not return to Rome until May 1814.

Napoleonic Wars

Third Coalition

In 1805 Britain convinced Austria and Russia to join a Third Coalition against France. Napoleon knew the French fleet could not defeat the Royal Navy and tried to lure it away from the English Channel in the hope a Spanish and French fleet could take control of the Channel long enough for French armies to cross to England. However, with Austria and Russia preparing an invasion of France, he had to change his plans and turn his attention to the continent. The newly formed Grande Armee secretly marched to Germany. On 20 October 1805, it surprised the Austrians at Ulm though the next day, Britain's victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, meant the British navy gained control of the seas. A few weeks later on 2 December, the first anniversary of his coronation, Napoleon defeated Austria and Russia at Austerlitz - a decisive victory he remained more proud of than any other. Again Austria had to sue for peace.

Fourth Coalition

The Fourth Coalition was assembled the following year, and Napoleon defeated Prussia at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt in October. He marched on against advancing Russian armies through Poland, and was involved at the bloody stalemate of the Battle of Eylau on 6 February 1807. After a decisive victory at Friedland, he signed a treaty at Tilsit in East Prussia with Tsar Alexander I of Russia, dividing Europe between the two powers. He placed puppet rulers on the thrones of German states, including his brother Jerome as king of the new state of Westphalia. In the French-controlled part of Poland, he established the Duchy of Warsaw, with King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony as ruler. Between 1809 and 1813, Napoleon also served as Regent of the Grand Duchy of Berg for his brother Louis Bonaparte.

In addition, Napoleon also waged economic war, attempting to enforce a Europe-wide commercial boycott of Britain called the " Continental System", though it had, "little success in its mission of destroying the economic organisation of Great Britain."

Peninsular War

Portugal did not comply with the Continental System and in 1807 Napoleon invaded Portugal with the support of Spain. Under the pretext of reinforcing the Franco-Spanish army occupying Portugal, Napoleon invaded Spain as well, replacing Charles IV with his brother Joseph and placing brother-in-law Joachim Murat in Joseph's stead at Naples. This led to resistance from the Spanish army and civilians in the Dos de Mayo Uprising.

Following a French retreat from much of the country, Napoleon himself took command and defeated the Spanish army, retook Madrid and then outmaneuvered a British army sent to support the Spanish, driving it to the coast. But before the Spanish population had been fully subdued, Austria again threatened war and Napoleon returned to France. The costly and often brutal Peninsular War continued, and Napoleon left several hundred thousand of his finest troops to battle Spanish guerrillas as well as British and Portuguese forces commanded by the Duke of Wellington. French control over the Iberian Peninsula deteriorated and collapsed in 1813; the war went on through allied victories and concluded after Napoleon's abdication in 1814.

Fifth Coalition

In 1809, Austria abruptly broke its alliance with France and Napoleon was forced to assume command of forces on the Danube and German fronts. After achieving early successes, the French faced difficulties crossing the Danube and then suffered a defeat in May at Aspern-Essling near Vienna. The Austrians failed to capitalize on the situation and allowed Napoleon's forces to regroup. The Austrians were defeated once again at Wagram and a new peace was signed between Austria and France. In the following year the Austrian Archduchess Marie Louise married Napoleon, following his divorce of Josephine.

The other member of the coalition was Britain. Along with fighting in the Iberian Peninsula, the British planned to open another front in mainland Europe. However, by the time the British landed at Walcheren, Austria had already sued for peace. The expedition was a disaster and was characterized by little fighting but 4,000 casualties thanks to the popularly dubbed "Walcheren Fever".

Invasion of Russia

The Congress of Erfurt had sought to preserve the Russo-French alliance and the leaders had had a friendly personal relationship after their first meeting in 1807. By 1811, however, tensions were building between the two nations and Alexander was under strong pressure from the Russian aristocracy to break off the alliance. The first clear sign the alliance was deteriorating was the easing of application of the Continental System in Russia, angering Napoleon. By 1812, advisors to Alexander suggested the possibility of invading the French Empire and the recapture of Poland.

Russia deployed large numbers of troops on the Polish borders, eventually placing more than 300,000 there of its total army strength of 410,000. After receiving initial reports of Russia's war preparations, Napoleon began expanding his Grande Armee to more than 450,000 men - in addition to at least 300,000 men already deployed in Iberia. Napoleon ignored repeated advice against an invasion of the vast Russian heartland, and prepared for an offensive campaign.

On 22 June 1812, Napoleon's invasion of Russia commenced. In an attempt to gain increased support from Polish nationalists and patriots, Napoleon termed the war the "Second Polish War" - the first Polish war being the liberation of Poland from Russia, Prussia and Austria. Polish patriots wanted the Russian part of partitioned Poland to be incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and a new Kingdom of Poland created, though this was rejected by Napoleon, who feared it would bring Prussia and Austria into the war against France. Napoleon also rejected requests to free the Russian serfs, fearing this might provoke a conservative reaction in his army's rear.

The Russians avoided a decisive engagement which Napoleon longed for, preferring to retreat ever deeper into Russia. A brief attempt at resistance was made at Smolensk in the middle of August, but the Russians were defeated in a series of battles in the area and Napoleon resumed his advance. The Russians then repeatedly avoided battle with the Grande Armee, though in a few cases this was only because Napoleon uncharacteristically hesitated to attack when the opportunity arose. Thanks to the Russian army's scorched earth tactics, the Grande Armee had more and more trouble foraging food for its men and horses. Along with hunger, the French also suffered from the harsh Russian winter.

The Russians eventually offered battle outside Moscow on 7 September. Losses were almost even, with slightly more casualties on the Russian side, after what may have been the bloodiest day of battle in history: the Battle of Borodino. Though Napoleon had won, the Russian army had accepted, and withstood, the major battle the French had hoped would be decisive. Napoleon's own account was: "Of the fifty battles I have fought, the most terrible was that before Moscow. The French showed themselves to be worthy victors, and the Russians can rightly call themselves invincible."

The Russian army withdrew and retreated past Moscow. Napoleon entered the city, assuming its fall would end the war and Alexander would negotiate peace. However, on orders of the city's military governor and commander-in-chief, Fyodor Rostopchin, rather than capitulating, Moscow was ordered burned. Within the month, fearing loss of control back in France, Napoleon and his army left.

The French suffered greatly in the course of a ruinous retreat; the Armee had begun as over 450,000 frontline troops, but in the end fewer than 40,000 crossed the Berezina River in November 1812, to escape. The strategy employed by the Russians had worn down the invaders and maintained the Tsar's domination over the Russian people. French losses in the campaign were 570,000 in total against around 400,000 Russian casualties and several hundred thousand civilian deaths.

Sixth Coalition, defeat and first exile

There was a lull in fighting over the winter of 1812–13 while both the Russians and the French recovered from their massive losses. A small Russian army harassed the French in Poland and eventually French troops withdrew to the German states to rejoin the expanding force there. This force continued to expand, with the French ultimately having a force of 360,000 troops in the field.

Heartened by Napoleon's losses in Russia, Prussia rejoined the Coalition that now included Russia, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Portugal. Napoleon assumed command in Germany and inflicted a series of defeats on the Allies culminating in the Battle of Dresden on 26–27 August 1813, causing almost 26,000 casualties to the Coalition forces, whilst the French sustained only around 8,000.

Despite these initial successes, the numbers continued to mount against Napoleon as Sweden and Austria joined the Coalition. Eventually the French army was pinned down by a force twice its size at the Battle of Leipzig from 16–19 October. Some of the German states switched sides in the midst of the battle to fight against France. This was by far the largest battle of the Napoleonic Wars and cost more than 90,000 casualties in total.

After this Napoleon withdrew back into France. His army was now reduced to 70,000 men still in formed units and 40,000 stragglers, against more than 3 times as many Allied troops. The French were surrounded and vastly outnumbered, with British armies pressing from the south, in addition to the Coalition forces moving in from the German states.

Paris was occupied on 31 March 1814 and Napoleon proposed the army march on the capital. His soldiers and regimental officers were eager to fight on, but his marshals mutinied. On 4 April, the marshals, led by Ney, confronted him. They said they refused to march. Napoleon asserted the army would follow him and Ney replied that the army would follow its generals. On 6 April 1814, Napoleon abdicated in favour of his son, but the Allies refused to accept this and demanded unconditional surrender. Napoleon abdicated again, unconditionally, on 11 April; however, the Allies allowed him to retain his title of Emperor. In the Treaty of Fontainebleau the victors exiled him to Elba, a small island in the Mediterranean 20 km off the coast of Italy. After his abdication Napoleon attempted to commit suicide by taking poison from a vial he carried. However, the poison had weakened with age and he survived to be deported to Elba. In exile, he ran Elba as a little country; he created a tiny navy and army, opened mines, and helped farmers improve their land.

The Hundred Days

In France, the royalists had taken over and restored Louis XVIII to power. Meanwhile Napoleon, separated from his wife and son (who had come under Austrian control), cut off from the allowance guaranteed to him by the Treaty of Fontainebleau, and aware of rumours he was about to be banished to a remote island in the Atlantic, escaped from Elba on 26 February 1815 and returned to the French mainland on 1 March 1815. Louis XVIII sent the 5th Regiment of the Line, led by Marshal Ney to meet him at Grenoble on 7 March 1815. Napoleon approached the regiment alone, dismounted his horse and, when he was within earshot of Ney's forces, shouted, "Soldiers of the Fifth, you recognise me. If any man would shoot his emperor, he may do so now." Following a brief silence, the soldiers shouted, "Vive L'Empereur!" With that, they marched with Napoleon to Paris. On 13 March, the powers at the Congress of Vienna declared him an outlaw and four days later the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Russia, Austria and Prussia bound themselves to put 150,000 men into the field to end his rule. Napoleon arrived in Paris on 20 March and governed for a period now called the Hundred Days. By the start of June the armed forces available to Napoleon had reached 200,000 and the French Army of the North crossed the frontier into the United Netherlands, in modern-day Belgium.

Napoleon was finally defeated by the Duke of Wellington and Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher at Waterloo on 18 June 1815. Wellington's army withstood repeated attacks by the French and drove them from the field, simultaneously the Prussians arrived in force and broke through Napoleon's right flank. The French army left the battlefield in disorder, allowing Coalition forces to enter France and restore Louis XVIII to the French throne.

Off the port of Rochefort, after considering an escape to the United States, Napoleon made his formal surrender to Captain Frederick Maitland of HMS Bellerophon on 15 July 1815.

Exile and death on Saint Helena

Napoleon was imprisoned and then exiled by the British in October 1815, to the island of St. Helena in the Atlantic Ocean, 2,000 km from any major landmass. Before Napoleon moved to Longwood House in November 1815, he lived in a pavilion on the estate The Briars belonging to William Balcombe (1779-1829), and became friendly with the family, especially the younger daughter Lucia Elizabeth (Betsy) who later wrote Recollections of the Emperor Napoleon. This relationship ended in March 1818 when Balcombe was accused of acting as an intermediary between Napoleon and Paris. Whilst there, with a small cadre of followers, he dictated his memoirs and criticised his captors. There were several plots to rescue Napoleon from captivity, including one from Brazil and another from Texas, where 400 exiled soldiers from the Grand Armee dreamed of a resurrection of the Napoleonic Empire in America. There was even a plan to rescue him using a submarine.

The question of the British treatment of Napoleon is a matter of dispute. His accommodation was poorly built, and the location was damp, windswept and generally considered unhealthy. The behaviour of Hudson Lowe exacerbated a difficult situation in the eyes of Napoleon and his supporters: the news that rescue expeditions were being planned by the Bonapartists in the United States led, for example, to the enforcement of stricter regulations in October 1816, Lowe causing sentries to be posted round Longwood garden at sunset instead of at 9 p.m. Napoleon and his entourage did not accept the legality or justice of his captivity, and the slights they received could become magnified. In the early years of exile Napoleon received many visitors, to the anger and consternation of the French minister Richelieu. From 1818 however, as the restrictions placed on him were increased, he lived the life of a recluse.

In 1818 The Times, which Napoleon received in exile, in reporting a false rumour of his escape, said this had been greeted by spontaneous illuminations in London. There was sympathy for him also in the political opposition in the British Parliament. Lord Holland, the nephew of Charles James Fox, the former Whig leader, made a speech to the House of Lords that the prisoner should be treated with no unnecessary harshness. Napoleon based his hopes for release on the possibility of Holland becoming Prime Minister.

Napoleon also enjoyed the support of Admiral Lord Cochrane who was closely involved in Chile and Brazil's struggle for independence. It was Cochrane's aim to rescue and then help him set up a new empire in South America, a scheme frustrated by Napoleon's death in 1821. For Lord Byron, amongst others, Napoleon was the epitome of the Romantic hero, the persecuted, lonely and flawed genius. Conversely, the news that Napoleon had taken-up gardening at Longwood appealed to more domestic British sensibilities.

Death

Napoleon died, having confessed his sins and received Extreme Unction and Viaticum at the hands of Father Ange Vignali on 5 May 1821. He had asked in his will to be buried on the banks of the Seine, but was buried on St. Helena, in the "valley of the willows". He was buried in an unmarked tomb.

In 1840 it was decided to return his remains to France and entomb them in a porphyry sarcophagus at Les Invalides, Paris. The Egyptian porphyry used for the tombs of Roman emperors was unavailable, so red quartzite was obtained from Russian Finland, eliciting protests from those who still remembered the Russians as enemies. On 8 October 1840, the coffin was exhumed and opened for two minutes. Those present claimed that the body remained in a state of perfect preservation. It was transported to France aboard the frigate Belle-Poule. The ship had been painted black for the occasion. On September 30, she arrived in Cherbourg, where, on 8 December, Napoleon's remains were transferred to the steamship Normandie. The Normandie transported the remains to Le Havre and up the Seine to Rouen, and on to Paris. On 15 December 1840 a state funeral was held; the hearse proceeded from the Arc de Triomphe down the Champs-Élysées, across the Place de la Concorde to the Esplanade and finally to the cupola in St Jerome's Chapel until the tomb (designed by Louis-Tullius-Joachim Visconti) was completed. On 3 April 1861 Napoleon's coffin was given its final resting place in the crypt under the dome. Hundreds of millions have since visited his tomb. A replica of his St. Helena tomb is also to be found at Les Invalides.

Cause of death

Francesco Antommarchi, the physician chosen by Napoleon's family, led the autopsy, and the cause of death was found to be stomach cancer. In the latter half of the twentieth century, several people claimed other causes for his death including deliberate arsenic poisoning.

Arsenic poisoning theory

In 1955 the diaries of Napoleon's valet, Louis Marchand, appeared in print. His description of Napoleon in the months before his death led Sten Forshufvud and Ben Weider, to conclude he had been killed by arsenic poisoning. Arsenic was used as a poison during the era because it was then undetectable when administered over a long period. As Napoleon's body was found to be remarkably well-preserved when it was moved in 1840, this supported the arsenic theory because arsenic is a strong preservative. Forshufvud and Weider noted Napoleon was attempting to quench abnormal thirst by drinking high levels of orgeat which contained cyanide compounds in the almonds used for flavouring and which, Forshufvud and Weider maintained, the antimony potassium tartrate used in his treatment, were preventing his stomach from expelling.

They claimed the thirst was a possible symptom of arsenic poisoning, and the calomel given to Napoleon became a massive overdose, causing stomach bleeding, killing him and leaving behind extensive tissue damage. Forshufvud and Weider suggested the autopsy doctors could have mistaken this damage for cancer after effects. A 2008 article showed the type of arsenic in the hair shafts was not of the organic type but of a mineral type suggesting the death was murder. Different researchers in another 2008 study analysed samples of Napoleon's hair from throughout his life, and also samples from his family and other contemporaries. All samples had high levels of arsenic, approximately 100 times higher than the current average. According to researchers, Napoleon's body was already heavily contaminated with arsenic as a boy, the high arsenic concentration in his hair was not due to poisoning and he was constantly exposed to arsenic from materials such as glues and dyes of the era. The body can tolerate quite large doses of arsenic if ingested regularly, and arsenic had become a fashionable cure-all from 1780.

Stomach cancer

The original autopsy concluded Napoleon died of stomach cancer without Antommarchi knowing Napoleon’s father had died of this form of cancer. In May 2005, a team of Swiss physicians claimed the reason for Napoleon's death was stomach cancer and in October a document was unearthed in Scotland presenting an account of the autopsy, which again seemed to confirm Antommarchi's conclusion. A 2007 study found no evidence of arsenic poisoning in the organs and concluded stomach cancer was the cause of death.

Religious Faith

Not long after Napoleon’s death Henry Parry Liddon asserted that Napoleon, while in exile on St. Helena, compared himself unfavourably to Christ. According to Liddon's sources, Napoleon said to Count Montholon that while he and others such as "Alexander, Caesar and Charlemagne" founded vast empires, their achievements relied on force, while Jesus "founded his empire on love." After further discourse about Christ and his legacy, Napoleon then reputedly said, "It...proves to me quite convincingly the Divinity of Jesus Christ."

An earlier quotation attributed to Napoleon suggested he may have been an admirer of Islam: "I hope the time is not far off when I shall be able to unite all the wise and educated men of all the countries and establish a uniform regime based on the principles of Qur'an which alone are true and which alone can lead men to happiness. However, Napoleon's private secretary during his conquest of Egypt, Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne, wrote in his memoirs that Napoleon had no serious interest in Islam or any other religion beyond their political value.

Marriages and children

Napoleon married Josephine de Beauharnais in 1796, when he was 26. He formally adopted her son Eugene and cousin Stephanie after assuming the throne, and arranged dynastic marriages for them. Josephine had her daughter Hortense marry Napoleon's brother, Louis.

Napoleon's and Josephine's marriage was unconventional, and both were known to have affairs. Josephine agreed to divorce so he could remarry in the hopes of producing an heir. Therefore in March 1810, he married Marie Louise, Archduchess of Austria by proxy; he had married into the family of German rulers. They remained married until his death, though she did not join him in exile. The couple had one child Napoleon Francis Joseph Charles (1811–32), known from birth as the King of Rome. He was later Napoleon II though he reigned for only two weeks. He was awarded the title of the Duke of Reichstadt in 1818 and had no children himself.

Napoleon acknowledged two illegitimate children: Charles, Count Léon, (1806–81) by Louise Catherine Eléonore Denuelle de la Plaigne and Alexandre Joseph Colonna, Count Walewski, (1810-68) by Countess Walewski. He may have had further illegitimate offspring: Emilie Pellapra, (1806-71) by Françoise-Marie LeRoy; Karl Eugin von Mühlfeld, by Victoria Kraus; Hélène Napoleone Bonaparte by Countess Albine de Montholon and Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire whose mother remains unknown.

Legacy

Napoleonic Code and the Nation State

The Napoleonic Code was adopted throughout much of Europe and remained in force after Napoleon's defeat. Napoleon himself said: "My true glory is not to have won 40 battles...Waterloo will erase the memory of so many victories. ... But...what will live forever, is my Civil Code." Dieter Langewiesche of the Tübingen University described the code as a "revolutionary project" which spurred the development of bourgeois society in Germany by expanding the right to own property and breaking feudalism. He also credits Napoleon with reorganising what had been the Holy Roman Empire, made-up of more than 1,000 entities, into a more streamlined network of 40 states, providing the basis for the German Confederation and the future unification of Germany under the German Empire in 1871. The movement of national unification in Italy was also precipitated by Napoleonic rule in the country. These changes contributed to the development of nationalism and the Nation state.

Bonapartism

Napoleon left a Bonapartist dynasty that would rule France again: his nephew, Napoleon III, became Emperor of the Second French Empire and was the first President of France. In a wider sense, Bonapartism now refers to a Marxist concept of a government that forms when class rule is not secure and a military, police, and state bureaucracy intervenes to establish order.

Autocracy

Napoleon is seen by John Abbott as having ended lawlessness and disorder. However, Napoleon has been compared with later autocrats: he was not overly troubled when facing the prospect of war and death for thousands and turned his search for undisputed rule into a series of conflicts throughout Europe, ignoring treaties and conventions alike.

Napoleon institutionalized systematic plunder and looting of conquered territories. French museums contain art stolen by Napoleon's forces from across Europe and brought to the Louvre in Paris for a grand central Museum; his example would later serve as inspiration for more notorious imitators.

He was considered a tyrant and usurper, by his opponents. When other European powers offered Napoleon terms that would have restored France's borders to positions which would have pleased the Bourbon kings, he refused compromise, and only accepted the surrender of his enemies.

Critics of Napoleon argue his true legacy was a loss of status for France and needless deaths: 'After all, the military record is unquestioned—17 years of wars, perhaps six million Europeans dead, France bankrupt, her overseas colonies lost. And it was all such a great waste, for...when the self-proclaimed tête d'armée was done, France's "losses were permanent" and she "began to slip from her position as the leading power in Europe to second-class status — that was Bonaparte's true legacy."' Napoleon's initial success may have sowed the seeds for his downfall; not used to such catastrophic defeats in the rigid power system of 18th century Europe, nations found life under the French yoke intolerable, sparking revolts, wars, and general instability that plagued the continent until 1815. Nevertheless, there are those in the international community who still admire his accomplishments.

Napoleon complex

British propaganda of the time depicted Napoleon as of smaller than average height and the image of him as a small man persists. However, confusion about his height has arisen as the French inch of the time equalled 2.7 centimetres, whilst the Imperial inch is 2.54 centimetres. According to contemporary sources, he in fact grew to just under 1.7 m, around average height for a Frenchman at the time. Napoleon's nickname of le petit caporal has added to the confusion, as non-Francophones have mistakenly interpreted petit by its literal meaning of "small". In fact, it is an affectionate term reflecting on his camaraderie with ordinary soldiers. Whether truly short or not, Napoleon's name has been lent to the Napoleon complex, a colloquial term describing a type of inferiority complex.

Warfare

In the area of military organisation, he borrowed from previous theorists and the reforms of preceding French governments and developed much of what was already in place, continuing for example the Revolution's policy of promotion based primarily on merit. Corps replaced divisions as the largest army units, artillery was integrated into reserve batteries, the staff system became more fluid, and cavalry once again became an important formation in French military doctrine. Though he is credited with introducing the concept of conscription, one of the restored monarchy's first acts was to end it.

Weapons and technology remained largely static through the Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, but 18th century operational strategy underwent massive restructuring. Napoleon's biggest influence came in the conduct of warfare, Carl von Clausewitz the influential military theorist regarded Napoleon as a true genius at this operational art of war.

A new emphasis towards the destruction, not just outmaneuvering, of enemy armies emerged. Invasions of enemy territory occurred over broader fronts, introducing strategic opportunities which made wars costlier and more decisive - this strategy became known as Napoleonic warfare, though he did not give it this name. The political aspects of war had been totally revolutionised, defeat for a European power now meant more than losing isolated enclaves, near- Carthaginian peaces intertwined whole national efforts – economic and militaristic – into collisions that upset international conventions.

Historians place the generalship of Napoleon as one of the greatest military strategists who ever lived, along with Alexander and Caesar. Wellington, when asked who was the greatest general of the day, answered: "In this age, in past ages, in any age, Napoleon."

Titles

|

Emperor Napoleon I of France

House of Bonaparte

|

||

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by French Directory |

Provisional Consul of France 11 November – 12 December 1799 Served alongside: Roger Ducos and Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès |

became Consul |

| New title Consulate created

|

First Consul of France 12 December 1799 – 18 May 1804 Served alongside: Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès (Second Consul) Charles-François Lebrun (Third Consul) |

became Emperor |

| Regnal titles | ||

| Vacant

Title last held by Louis XVIas King of the French |

Emperor of the French 18 May 1804 – 6 April 1814 |

Succeeded by Louis XVIII as King of France and Navarre |

| Preceded by Francis II |

King of Italy 26 May 1805 – 1814 |

Vacant Title next held by Vittorio Emanuele II |

| Preceded by Louis XVIII as King of France and Navarre |

Emperor of the French 1 March – 22 June 1815 |

Succeeded by Napoleon II |

| New title State created

|

Protector of the Confederation of the Rhine 12 July 1806 – 19 October 1813 |

Rhine Confederation dissolved successive ruler:

Francis I, Emperor of Austria as President of the German Confederation |

| Titles in pretence | ||

| New title | — TITULAR — Emperor of the French 6 April 1814 – 1 March 1815 |

Vacant Title next held by Napoleon II |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Bonaparte, Napoleon |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Napoleon I Bonaparte, Emperor of the French, King of Italy |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | French general and ruler |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 15 August 1769 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ajaccio, Corsica |

| DATE OF DEATH | 5 May 1821 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | St. Helena |