History of Europe

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: History

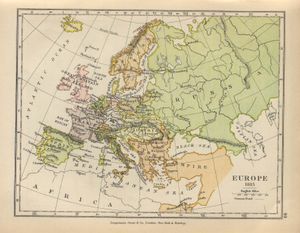

The history of Europe describes the passage of time from humans inhabiting the European continent to the present day. The first evidence of people living in Europe dates back to 35,000 BC. Europe's ancient classical antiquity dates from Homer's Iliad in Ancient Greece of around 700 BC. The Roman Republic was established in 509 BC, which was usurped by Octavian's new Roman Empire at its first century peak. Christian religion was adopted in the fourth century, and in the sixth was organized, within the Empire, by Emperor Justinian I (527–565) as a Pentarchy of sees in its five most important cities: Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria. Faced with attacking hordes and plague, the Empire crumbled into east and west, and the dark ages gripped the heart of Western Europe. The Byzantine Empire kept the light of civilization burning in the East. A schism within the church's authority in 1054 was added to the earlier division that had persisted since 451 and was followed by Crusades from west to rescue the east from Muslim invasion. Feudal society began to break down, as the Mongol invaders carried the Black Death with them. Constantinople fell in 1453, yet the new world was discovered in 1492. Europe awoke from the medieval period through rediscovery of classical learning. Renaissance was followed by the Protestant Reformation, as German priest Martin Luther attacked Papal authority. The Thirty Years War, the Treaty of Westphalia and the Glorious Revolution laid the basis for a new era of expansion and enlightenment.

The Industrial Revolution, beginning in Great Britain, allowed people for the first time to break from material subsistence. The early British Empire split as its colonies in America revolted to establish a representative government. Political change in continental Europe was spurred by the French Revolution, as people cried out for liberté, egalité, fraternité. The ensuing French leader, Napoleon, conquered and reformed the social structure of the continent through war up to 1815. As more and more small property holders were granted the vote, in France and the UK, socialist and trade union activity developed and revolution gripped Europe in 1848. The last vestiges of serfdom were abolished in Austria-Hungary in 1848. Russian serfdom was abolished in 1861. The Balkan nations began to regain their independecne from the Ottoman Empire. After the Franco-Prussian War, Italy and Germany were formed from the groups of principalities in 1870 and 1871. Conflict spread across the globe, in a chase for empires, until the search for a place in the sun ended with the outbreak of World War One. In the desperation of war, the Russian Revolution promised the people "peace, bread and land". The defeat of Germany came at the price of economic destruction, codified into the Treaty of Versailles, manifested in the Great Depression and the return to a Second World War. With the victory of capitalism and communism over fascism, a cold new world order took shape. Western Europe formed a free trade area, divided by the Iron Curtain of the Soviet Union. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, Europe signed a new treaty of union, which in 2007 encompasses 27 European countries.

| History of Europe Timeline | |

|---|---|

| 360 BC | Plato attacks Athenian democracy in the Republic. |

| 323 BC | Alexander the Great dies and his Macedonian Empire fragments. |

| 44 BC | Julius Caesar is murdered. The Roman Republic drawing to a close. |

| 27 BC | Establishment of the Roman Empire under Octavian. |

| 330 | Constantine makes Constantinople into his capital, a new Rome. |

| 395 | Following the death of Theodosius I, the Empire is permanently split into eastern and western halves. |

| 527 | Justinian I is crowned emperor of Byzantium. |

| 800 | Coronation of Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor. |

| 1054 | Start of the East-West Schism, which divides the Christian church for centuries. |

| 1066 | Successful Norman Invasion of England by William the Conqueror. |

| 1095 | Pope Urban II calls for the First Crusade. |

| 1340 | Black Death kills a third of Europe's population. |

| 1337 - 1453 | The Hundred Years War |

| 1453 | Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks. |

| 1492 | Christopher Columbus lands in the New World. |

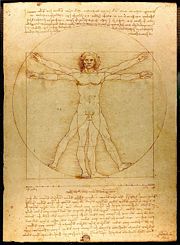

| 1498 | Leonardo da Vinci paints The Last Supper in Milan, as the Renaissance flourishes. |

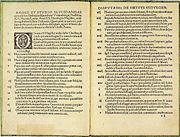

| 1517 | Martin Luther nails his demands for Reformation to the door of the church in Wittenberg. |

| 1648 | The Peace of Westphalia ends the Thirty Years' War. |

| 1789 | The French Revolution. |

| 1815 | Following the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte the Treaty of Vienna is signed. |

| 1860s | Russia emancipates its serfs and Karl Marx completes the first volume of Das Kapital. |

| 1914 | Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria is assassinated and World War One begins. |

| 1945 | The Second World War ends with Europe in ruins. |

| 1989 - 1992 | The Berlin Wall comes down and the Treaty of the European Union is signed in Maastricht. |

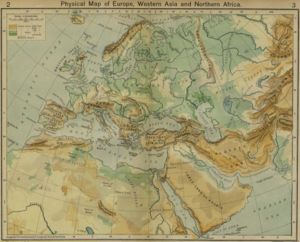

Prehistory

Homo erectus and Neanderthals settled Europe long before the emergence of modern humans, Homo sapiens. The bones of the earliest Europeans are found in Dmanisi, Georgia, dated at 1.8 million years before the present. The earliest appearance of anatomically modern people in Europe has been dated to 35,000 BC. Evidence of permanent settlement dates from the 7th millennium BC in Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece. The Neolithic reached Central Europe in the 6th millennium BC and parts of Northern Europe in the 5th and 4th millennium BC. The Trypillian civilization 5508-2750 BC was the first big civilization in Europe and among the earliest in the world, it was located in modern Ukraine and also in Moldavia and Romania. It was probably earlier than even the Sumerians in the near east. The Trypillyan had cities with 15,000 citizens 6,000 years ago who covered 450 hectares.

Also known as the Copper Age, European Chalcolithic is a time of changes and confusion. The most relevant fact is the infiltration and invasion of large parts of the territory by people originating from Central Asia, considered by mainstream scholars to be the original Indo-Europeans, although there are again several theories in dispute. Other phenomena are the expansion of Megalithism and the appearance of the first significant economic stratification and, related to this, the first known monarchies in the Balkan region. The first well-known literate civilization in Europe was that of the Minoans of the island of Crete and later the Mycenaens in the adjacent parts of Greece, starting at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC.

Though the use of iron was known to the Aegean peoples about 1100 BCE, it didn't reach Central Europe before 800 BCE, giving way to the Hallstatt culture, an Iron Age evolution of the culture the Urn Fields. Probably as by-product of this technological superiority of the Indo-Europeans, soon after, they clearly consolidate their positions in Italy and Iberia, penetrating deep inside those peninsulas (Rome founded in 753 BCE).

Classical worlds

The Greeks and the Romans left a legacy in Europe which is evident in current language, thought, law and minds. Ancient Greece was a collection of city-states, out of which a primitive form of democracy developed. Athens was the most powerful and developed city, and a cradle of learning from the time of Pericles. Citizens forums debated and legislated policy of the state, and from here arose one of the most notable classical philosophers, Socrates. An incessant inquirer, Socrates was put on trial and sentenced to death for "corrupting the youth" of Athens, when his discussions conflicted with the established religious beliefs of the time. Plato, a pupil of Socrates, recorded this episode in his writings, and went on to develop his own unique philosophy, Platonism. His student, Aristotle, taught Alexander the Great, who spread Hellenistic culture and learning to the banks of the River Indus. But the Roman Republic, strengthened through victory over Carthage in the Punic Wars was rising in the region. Greek wisdom passed into Roman institutions, as Athens itself was absorbed under the banner of the Senate and People of Rome ( Senatus Populusque Romanus). The Romans expanded from Arabia to Britannia. In 44 BC as it approached its height, its leader Julius Caesar was murdered on suspicion of subverting the Republic, to become dictator. In the ensuing turmoil, Octavian usurped the reigns of power and bought the Roman Senate. While proclaiming the rebirth of the Republic, he had in fact ushered in the transfer of the Roman state from a republic to an empire, Roman Empire.

Ancient Greece

- Homer, Iliad, Polis

- Greco-Persian Wars

- Delian League, Pericles, Peloponnesian War

- Athenian democracy

- Socrates, Plato, Aristotle

- Alexander the Great

- Macedon

Civic Hellenism

The Hellenic civilization took the form of a collection of city-states (the most important being Athens, Corinth, Syracuse and Sparta), having vastly differing types of government and cultures, including what are unprecedented developments in various governmental forms, philosophy, science, mathematics, politics, sports, theatre and music. The Hellenic city-states founded a large number of colonies on the shores of the Black Sea and the Mediterranean sea, Asia Minor, Sicily and Southern Italy in Magna Graecia, but in the 4th century BC their internal wars made them an easy prey for king Philip II of Macedon. The campaigns of his son Alexander the Great spread Greek culture into Persia, Egypt and India, but also favoured contact with the older learnings of those countries, opening up a new period of development, known as Hellenism.

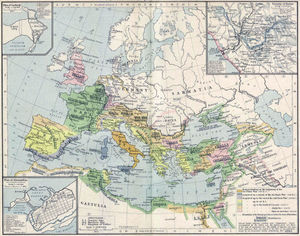

The rise of Rome

Much of Greek learning was assimilated by the nascent Roman state as it expanded outward from Italy, taking advantage of its enemies' inability to unite: the only real challenge to Roman ascent came from the Phoenician colony of Carthage, and its defeat in the end of the 3rd century BC marked the start of Roman hegemony. First governed by kings, then as a senatorial republic (the Roman Republic), Rome finally became an empire at the end of the 1st century BC, under Augustus and his authoritarian successors. The Roman Empire had its centre in the Mediterranean Sea, controlling all the countries on its shores; the northern border was marked by the Rhine and Danube rivers; under emperor Trajan (2nd century AD) the empire reached its maximum expansion, including Britain, Romania and parts of Mesopotamia. The empire brought peace, civilization and an efficient centralized government to the subject territories, but in the 3rd century a series of civil wars undermined its economic and social strength. In the 4th century, the emperors Diocletian and Constantine were able to slow down the process of decline by splitting the empire into a Western and an Eastern part. Whereas Diocletian severely persecuted Christianity, Constantine declared an official end to state-sponsored persecution of Christians in 313 with the Edict of Milan, thus setting the stage for the empire to later become officially Christian in about 380 (which would cause the Church to become an important institution).

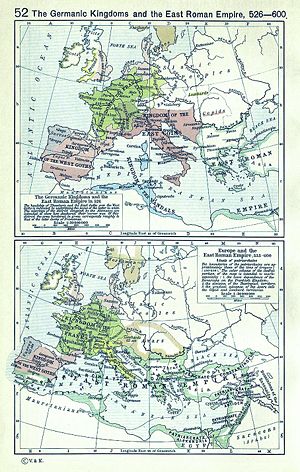

Dark Ages

When Emperor Constantine had reconquered Rome under the banner of the cross in 312, he soon afterwards issued the Edict of Milan in 313, declaring the legality of Christianity in the Roman Empire. In addition, Constantine officially shifted the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to the Greek town of Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople ("City of Constantine"). In 395 Theodosius I, who had made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire, would be the last emperor to preside over a united Roman Empire, and from thenceforth, the empire would be split into two halves: the Western Roman Empire centered in Ravenna, and the Eastern Roman Empire (later to be referred to as the Byzantine Empire) centered in Constantinople. The Western Roman Empire was repeatedly attacked by marauding Germanic tribes (see: Migration Period), and in 476 finally fell to the Heruli chieftan Odoacer. Roman authority in the West completely collapsed and the western provinces soon became a patchwork of Germanic kingdoms. However, the city of Rome, under the guidance of the Roman Catholic Church still remained a centre of learning, and did much to preserve classic Roman thought in Western Europe. In the meantime, the Roman emperor in Constantinople, Justinian I, had succeeded in codifying all Roman law into the Corpus Juris Civilis (529-534). For the duration of the 6th century, the Eastern Roman Empire was embroiled in a series of deadly conflicts, first with the Persian Sassanid Empire, followed by the onslaught of the arising Islamic caliphate ( Umayyad Dynasty). By 650, the provinces of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria were lost to the Muslim forces. In the Western Europe, a poltical structure was emerging: in the power vacuum left in the wake of Rome's collapse, localised hierarchies were based on the bond of common people to the land on which they worked. Tithes were paid to the lord of the land, and the lord owed duties to the regional prince. The tithes were used to pay for the state and wars. This was the feudal system, in which new princes and kings arose, the greatest of which was the Frank ruler Charlemagne. In 800, Charlemagne, reinforced by his massive territorial conquests, was crowned Emperor of the Romans (Imperator Romanorum) by Pope Leo III, effectively solidifying his power in western Europe. Charlemagne's reign marked the beginning of a new Germanic Roman Empire in the west, the Holy Roman Empire. Outside his borders, new forces were gathering. The Kievan Rus' were marking out their territory, a Great Moravia was growing, while the Angles and the Saxons were securing their borders.

The shadows of Rome

The Roman Empire had been repeatedly attacked by barbarian hordes from Northern Europe and in 476, Rome finally fell. Romulus Augustus, the last Emperor of the Western Roman Empire surrendered to the Hun King Odoacer. British historian Edward Gibbon argued in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776) that the Romans had become decadent, they had lost civic virtue. Gibbon said that the adoption of Christianity, meant belief in a better life after death, and therefore made people lazy and indifferent to the present. "From the eighteenth century onward", Glen W. Bowersock has remarked, "we have been obsessed with the fall: it has been valued as an archetype for every perceived decline, and, hence, as a symbol for our own fears." It remains one of the greatest historical questions, and has a tradition rich in scholarly interest.

Some other notable dates are the Battle of Adrianople in 378, the death of Theodosius I in 395 (the last time the Roman Empire was politically unified), the crossing of the Rhine in 406 by Germanic tribes after the withdrawal of the legions in order to defend Italy against Alaric I, the death of Stilicho in 408, followed by the disintegration of the western legions, the death of Justinian I, the last Roman Emperor who tried to reconquer the west, in 565, and the coming of Islam after 632. Many scholars maintain that rather than a "fall", the changes can more accurately be described as a complex transformation. Over time many theories have been proposed on why the Empire fell, or whether indeed it fell at all.

A Byzantine light

Many consider Emperor Constantine I (reigned AD 306–337) to be the first " Byzantine Emperor". It was he who moved the imperial capital in 324 AD from Nicomedia to Byzantium, refounded as Constantinople, or Nova Roma (" New Rome"). The city of Rome itself had not served as the capital since the reign of Diocletian. Some date the beginnings of the Empire to the reign of Theodosius I (379–395) and Christianity's official supplanting of the pagan Roman religion, or following his death in 395, when the political division between East and West became permanent. Others place it yet later in 476, when Romulus Augustulus, traditionally considered the last western Emperor, was deposed, thus leaving sole imperial authority with the emperor in the Greek East. Others point to the reorganization of the empire in the time of Heraclius (ca. 620) when Latin titles and usages were officially replaced with Greek versions. In any case, the changeover was gradual and by 330, when Constantine inaugurated his new capital, the process of hellenization and increasing Christianization was already under way. The Empire is generally considered to have ended after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

The Plague of Justinian was a pandemic that afflicted the Byzantine Empire, including its capital Constantinople, in the years 541–542 AD. It is estimated that the Plague of Justinian killed as many as 100 million people across the world. It caused the Europe's population to drop by around 50% between 541 and 700. It also may have contributed to the success of the Arab conquests.

Feudal Christendom

The Holy Roman Empire emerged around 800, as Charlemagne, king of the Franks, was crowned by the pope as emperor. His empire based in modern France, the Low Countries and Germany expanded into modern Hungary, Italy, Bohemia, Lower Saxony and Spain. He and his father received substantial help from an alliance with the Pope, who wanted help against the Lombards. The pope was officially a vassal of the Byzantine Empire, but the Byzantine emperor did (could do) nothing against the Lombards.

To the east Bulgaria was established in 681 and became the first Slavic country. The powerful Bulgarian Empire was the main rival of Byzantium for control of the Balkans for centuries and from the 9th century became the cultural centre of Slavic Europe. Two states, Great Moravia and Kievan Rus', emerged among the Western and Eastern Slavs respectively in the 9th century. In the late 9th century and 10th century, northern and western Europe felt the burgeoning power and influence of the Vikings who raided, traded, conquered and settled swiftly and efficiently with their advanced sea-going vessels such as the longships. The Hungarians pillaged mainland Europe, the Pechenegs raided eastern Europe and the Arabs the south. In the 10th century independent kingdoms were established in Central Europe, for example, Poland and Kingdom of Hungary. Hungarians had stopped their pillaging campaigns; prominent nation states also included Croatia and Serbia in the Balkans. The subsequent period, ending around 1000, saw the further growth of feudalism, which weakened the Holy Roman Empire.

High feudalism

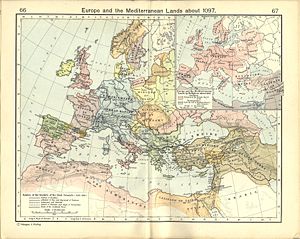

The slumber of the Dark Ages was shaken by renewed crisis in the Church. In 1054 a schism, an insoluble split, between the two remaining Christian seats in Rome and Constantinople.

A divided church

The Great Schism between the Western and Eastern Christian Churches was sparked in 1054 by Pope Leo IX asserting authority over three of the seats in the Pentarchy, in Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria. Since the mid eighth century, the Byzantine Empire's borders had been shrinking in the face of Islamic expansion. Antioch had been wrested back into Byzantine control by 1045, but the resurgent power of the Roman successors in the West claimed a right and a duty for the lost seats in Asia and Africa. One holy catholic and apostolic church. Pope Leo sparked a further dispute by defending the filioque clause in the Nicene Creed which the West had adopted customarily. Eastern Orthodox today state that the 28th Canon of the Fourth Ecumenical Council explicitly proclaimed the equality of the Bishops of Rome and Constantinople. The Orthodox also state that the Bishop of Rome has authority only over his own diocese and does not have any authority outside his diocese. There were other less significant catalysts for the Schism however, including variance over liturgical. The Schism of Catholic and Orthodox followed centuries of estrangement between Latin and Greek worlds.

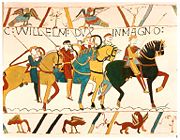

Further changes were set afoot with a redivision of power in Europe. William the Conqueror, a King of Normandy invaded England in 1066. The Norman Conquest was a pivotal event in English history for several reasons. This conquest linked England more closely with continental Europe through the introduction of a Norman aristocracy, thereby lessening Scandinavian influence. It created one of the most powerful monarchies in Europe and engendered a sophisticated governmental system.

Holy wars

After the East-West Schism, Western Christianity was adopted by newly created kingdoms of Central Europe: Poland, Hungary and Bohemia. The Roman Catholic Church developed as a major power, leading to conflicts between the Pope and Emperor. In 1129 AD the Roman Catholic Church established the Inquisition to make Western Europeans Roman Catholic by force. The Inquisition punished those who practiced heresy (heretics)to make them repent. If they could not do so, the penalty was death. During this time many Lords and Nobles ruled the church. The Monks of Cluny worked hard to establish a church where there were no Lords or Nobles ruling it. They succeeded. Pope Gregory VII continued the work of the monks with 2 main goals, to rid the church of control by kings and nobles and to increase the power of the pope. The area of the Roman Catholic Church expanded enormously due to conversions of pagan kings ( Scandinavia, Lithuania, Poland, Hungary) and crusades. Most of Europe was Roman Catholic in the 15th century.

Early signs of the rebirth of civilization in western Europe began to appear in the 11th century as trade started again in Italy, leading to the economic and cultural growth of independent city states such as Venice and Florence; at the same time, nation-states began to take form in places such as France, England, Spain, and Portugal, although the process of their formation (usually marked by rivalry between the monarchy, the aristocratic feudal lords and the church) actually took several centuries. These new nation-states began writing in their own cultural vernaculars, instead of the traditional Latin. Notable figures of this movement would include Christine de Pisan and Dante, the former writing in French, and the latter in Italian.(See Reconquista for the latter two countries.) On the other hand, the Holy Roman Empire, essentially based in Germany and Italy, further fragmented into a myriad of feudal principalities or small city states, whose subjection to the emperor was only formal.

The 13th and 14th century, when the Mongol Empire came to power, is often called the Age of the Mongols. Mongol armies expanded westward under the command of Batu Khan. Their western conquests included almost all of Russia (save Novgorod, which became a vassal), Hungary, and Poland (Which had remained sovereign state). Mongolian records indicate that Batu Khan was planning a complete conquest of the remaining European powers, beginning with a winter attack on Austria, Italy and Germany, when he was recalled to Mongolia upon the death of Great Khan Ögedei. Most historians believe only his death prevented the complete conquest of Europe. In Russia, the Mongols of the Golden Horde ruled for almost 250 years.

Black Death

One of the largest catastrophes to have hit Europe was the Black Death. There were numerous outbreaks, but the most severe was in the mid-1300s and is estimated to have killed a third of Europe's population.

Beginning in the 14th century, the Baltic Sea became one of the most important trade routes. The Hanseatic League, an alliance of trading cities, facilitated the absorption of vast areas of Poland, Lithuania and other Baltic countries into the economy of Europe. This fed the growth of powerful states in Eastern Europe including Poland, Hungary, Bohemia, and Muscovy. The conventional end of the Middle Ages is usually associated with the fall of the city Constantinople and of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The Turks made the city the capital of their Ottoman Empire, which lasted until 1922 and also included Egypt, Syria and most of the Balkans. The Ottoman wars in Europe, also sometimes referred as the Turkish wars, marked an essential part of the history of southeastern Europe.

- Hanseatic League, Marco Polo, Lex Mercatoria, History of trade

- Western Schism (1378-1417)

- Hundred Years War, Joan of Arc

Europe's awakening

Renaissance

Petrarch wrote in the 1330s: "I am alive now, yet I would rather have been born in another time." He was enthusiastic about Greek and Roman antiquity — great men who were dead. Matteo Palmieri wrote in the 1430s: "Now indeed may every thoughtful spirit thank god that it has been permitted to him to be born in a new age." The renaissance was born: a new age where learning was very important.

The Renaissance was inspired by the growth in study of Latin and Greek texts and the admiration of the Greco-Roman era as a golden age. This prompted many artists and writers to begin drawing from Roman and Greek examples for their works, but there was also much innovation in this period, especially by multi-faceted artists such as Leonardo da Vinci. Much of the Greek texts came from Islamic sources, who also improved upon them. Important political precedents were also set in this period. Niccolò Machiavelli's political writing in The Prince influenced later absolutism and real-politik; also important were the many patrons who ruled states and used the artistry of the Renaissance as a sign of their power.

Reformation

During this period corruption in the Catholic Church led to a sharp backlash in the Protestant Reformation. It gained many followers especially among princes and kings seeking a stronger state by ending the influence of the Catholic Church. Figures other than Martin Luther began to emerge as well like John Calvin whose Calvinism had influence in many countries and King Henry VIII of England who broke away from the Catholic Church in England and set up the Anglican Church. These religious divisions brought on a wave of wars inspired and driven by religion but also by the ambitious monarchs in Western Europe who were becoming more centralized and powerful.

The Protestant Reformation also led to a strong reform movement in the Catholic Church called the Counter-Reformation, which aimed to reduce corruption as well as to improve and strengthen Catholic Dogma. An important group in the Catholic Church who emerged from this movement were the Jesuits who helped keep Eastern Europe within the Catholic fold. Still, the Catholic Church was intensely weakened by the Reformation, large parts of Europe were no longer under its sway and kings in the remaining Catholic countries began to take control of the Church institutions within their kingdoms.

Unlike Western Europe, the countries of Central Europe, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Hungary, were more tolerant. While still enforcing the predominance of Catholicism they continued to allow the large religious minorities to maintain their faiths. Central Europe became divided between Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox and Jews. Another important development in this period was the growth of pan-European sentiments. Eméric Crucé (1623) came up with the idea of the European Council, intended to end wars in Europe; attempts to create lasting peace were no success, although all European countries (except the Russian and Ottoman Empires, regarded as foreign) agreed to make peace in 1518 at the Treaty of London. Many wars broke out again in a few years. The Reformation also made European peace impossible for many centuries.

Another development was the idea of European superiority. The ideal of civilization was taken over from the ancient Greeks and Romans: discipline, education and living in the city were required to make people civilized; Europeans and non-Europeans were judged for their civility, and Europe regarded itself as superior to other continents. There was a movement by some such as Montaigne that regarded the non-Europeans as a better, more natural and primitive people. Post services were founded all over Europe, which allowed a humanistic interconnected network of intellectuals across Europe, despite religious divisions. However, the Roman Catholic church banned many leading scientific works; this led to an intellectual advantage for Protestant countries, where the banning of books was regionally organized. Francis Bacon and other advocates of science tried to create unity in Europe by focusing on the unity in nature.1 In the 15th century, at the end of the Middle Ages, powerful states were appearing, built by the New Monarchs who were centralizing power in France, England, and Spain. On the other hand the Parliament in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth grew in power, taking legislative rights from the Polish king. The new state power was contested by parliaments in other countries especially England. New kinds of states emerged which were cooperations between territorial rulers, cities, farmer republics and knights.

Discovery

The numerous wars did not prevent the new states from exploring and conquering wide portions of the world, particularly in Asia ( Siberia) and the newly-discovered Americas. In the 15th century, Portugal led the way in geographical exploration, followed by Spain in the early 16th century. They were the first states to set up colonies in America and trade stations on the shores of Africa and Asia, but they were soon followed by France, England and the Netherlands. In 1552, Russian tsar Ivan the Terrible conquered two major Tatar khanates, Kazan and Astrakhan, and the Yermak's voyage of 1580 led to the annexation of Siberia into Russia.

Colonial expansion proceeded in the following centuries (with some setbacks, such as the American Revolution and the wars of independence in many American colonies). Spain had control of part of North America and a great deal of Central America and South America, the Caribbean and the Philippines; Britain took the whole of Australia and New Zealand, most of India, and large parts of Africa and North America; France held parts of Canada and India (nearly all of which was lost to Britain in 1763), Indochina, large parts of Africa and Caribbean islands; the Netherlands gained the East Indies (now Indonesia) and islands in the Caribbean; Portugal obtained Brazil and several territories in Africa and Asia; and later, powers such as Germany, Belgium, Italy and Russia acquired further colonies.

This expansion helped the economy of the countries owning them. Trade flourished, because of the minor stability of the empires. By the late 16th century American silver accounted for one-fifth of the Spain's total budget. The European countries fought wars that were largely paid for by the money coming in from the colonies. Nevertheless, the profits of the slave trade and of plantations of the West Indies, most profitable of all the British colonies at that time, amounted to less than 5% of the British Empire's economy at the time of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century.

Enlightenment

The Reformation had profound effects on the unity of Europe. Not only were nations divided one from another by their religious orientation, but some states were torn apart internally by religious strife, avidly fostered by their external enemies. France suffered this fate in the 16th century in the series of conflicts known as the French Wars of Religion, which ended in the triumph of the Bourbon Dynasty. England avoided this fate for a while and settled down under Elizabeth to a moderate Anglicanism. Much of modern day Germany was divided into numerous small states under the theoretical framework of the Holy Roman Empire, was also divided along internally drawn sectarian lines, until the Thirty Years' War seemed to see religion replaced by nationalism as the motor of European conflict. The single exception to this was the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, an entity created by the Union of Lublin, highly valuing religious tolerance.

Throughout the early part of this period, capitalism was replacing feudalism as the principal form of economic organization, at least in the western half of Europe. The expanding colonial frontiers resulted in a Commercial Revolution. The period is noted for the rise of modern science and the application of its findings to technological improvements, which culminated in the Industrial Revolution. Iberian (Spain and Portugal) exploits of the New World, which started with Christopher Columbus's venture westward in search of a quicker trade route to the East Indies in 1492, was soon challenged by English and French exploits in North America. New forms of trade and expanding horizons made new developments in international law necessary.

After the Treaty of Westphalia which ended the Thirty Years' War, Absolutism became the norm of the continent, while parts of Europe experimented with constitutions foreshadowed by the English Civil War and particularly the Glorious Revolution. European military conflict did not cease, but had less disruptive effects on the lives of Europeans. In the advanced north-west, the Enlightenment gave a philosophical underpinning to the new outlook, and the continued spread of literacy, made possible by the printing press, created new secular forces in thought. Again, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth would be an exception to this rule, with its unique quasi-democratic Golden Freedom.

Eastern Europe was an arena of conflict for domination between Sweden, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire. This period saw a gradual decline of these three powers which were eventually replaced by new enlightened absolutist monarchies, Russia, Prussia and Austria. By the turn of the 19th century they became new powers, having divided Poland between them, with Sweden and Turkey having experienced substantial territorial losses to Russia and Austria respectively. Numerous Polish Jews emigrated to Western Europe, founding Jewish communities in places where they had been expelled from during the Middle Ages.Welos had a profound impact on this.

Revolution and nationalism

Industrial revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period in the late 18th and early 19th centuries when major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation had a profound effect on socioeconomic and cultural conditions in Britain and subsequently spread throughout Europe and North America and eventually the world, a process that continues as industrialisation. In the later part of the 1700s the manual labour based economy of the Kingdom of Great Britain began to be replaced by one dominated by industry and the manufacture of machinery. It started with the mechanisation of the textile industries, the development of iron-making techniques and the increased use of refined coal. Once started it spread. Trade expansion was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways. The introduction of steam power (fuelled primarily by coal) and powered machinery (mainly in textile manufacturing) underpinned the dramatic increases in production capacity. The development of all-metal machine tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the manufacture of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries. The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century, eventually affecting most of the world. The impact of this change on society was enormous.

Political revolution

French intervention in the American Revolutionary War had bankrupted the state. After repeated failed attempts at financial reform, Louis XVI was persuaded to convene the Estates-General, a representative body of the country made up of three estates: the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. The members of the Estates-General assembled in the Palace of Versailles in May 1789, but the debate as to which voting system should be used soon became an impasse. Come June, the third estate, joined by members of the other two, declared itself to be a National Assembly and swore an oath not to dissolve until France had a constitution and created, in July, the National Constituent Assembly. At the same time the people of Paris revolted, famously storming the Bastille prison on 14 July 1789.

At the time the assembly wanted to create a constitutional monarchy, and over the following two years passed various laws including the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the abolition of feudalism, and a fundamental change in the relationship between France and Rome. At first the king went along with these changes and enjoyed reasonable popularity with the people, but as anti-royalism increased along with threat of foreign invasion, the king, stripped of his power, decided to flee along with his family. He was recognized and brought back to Paris. On 12 January 1793, having been convicted of treason, he was executed.

On 20 September 1792 the National Convention abolished the monarchy and declared France a republic. Due to the emergency of war the National Convention created the Committee of Public Safety, controlled by Maximilien Robespierre of the Jacobin Club, to act as the country's executive. Under Robespierre the committee initiated the Reign of Terror, during which up to 40,000 people were executed in Paris, mainly nobles, and those convicted by the Revolutionary Tribunal, often on the flimsiest of evidence. Elsewhere in the country, counter-revolutionary insurrections were brutally suppressed. The regime was overthrown in the coup of 9 Thermidor ( 27 July 1794) and Robespierre was executed. The regime which followed ended the Terror and relaxed Robespierre's more extreme policies.

Napoleon Bonaparte was France's most successful general in the Revolutionary wars, having conquered large parts of Italy and forced the Austrians to sue for peace. In 1799 he returned from Egypt and on 18 Brumaire ( 9 November) overthrew the government, replacing it with the Consulate, in which he was First Consul. On 2 December 1804, after a failed assassination plot, he crowned himself Emperor. In 1805, Napoleon planned to invade Britain, but a renewed British alliance with Russia and Austria ( Third Coalition), forced him to turn his attention towards the continent, while at the same time failure to lure the superior British fleet away from the English Channel, ending in a decisive French defeat at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October put an end to hopes of an invasion of Britain. On 2 December 1805, Napoleon defeated a numerically superior Austro-Russian army at Austerlitz, forcing Austria's withdrawal from the coalition (see Treaty of Pressburg) and dissolving the Holy Roman Empire. In 1806, a Fourth Coalition was set up, on 14 October Napoleon defeated the Prussians at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt, marched through Germany and defeated the Russians on 14 June 1807 at Friedland, the Treaties of Tilsit divided Europe between France and Russia and created the Duchy of Warsaw.

On 12 June 1812 Napoleon invaded Russia with a Grande Armée of nearly 700,000 troops. After the measured victories at Smolensk and Borodino Napoleon occupied Moscow, only to find it burned by the retreating Russian Army, he was forced to withdraw, on the march back his army was harassed by Cossacks, and suffered disease and starvation. Only 20,000 of his men survived the campaign. By 1813 the tide had began to turn from Napoleon, having been defeated by a seven nation army at the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813. He was forced to abdicate after the Six Days Campaign and the occupation of Paris, under the Treaty of Fontainebleau he was exiled to the Island of Elba. He returned to France on 1 March 1815 (see Hundred Days), raised an army, but was comprehensively defeated by a British and Prussian force at the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815.

Nations rising

After the defeat of revolutionary France, the other great powers tried to restore the situation which existed before 1789. In 1815 at the Congress of Vienna, the major powers of Europe managed to produce a peaceful balance of power among the empires after the Napoleonic wars (despite the occurrence of internal revolutionary movements) under the Metternich system. However, their efforts were unable to stop the spread of revolutionary movements: the middle classes had been deeply influenced by the ideals of democracy of the French revolution, the Industrial Revolution brought important economical and social changes, the lower classes started to be influenced by socialist, communist and anarchistic ideas (especially those summarized by Karl Marx in The Communist Manifesto), and the preference of the new capitalists became Liberalism. Further instability came from the formation of several nationalist movements (in Germany, Italy, Poland etc.), seeking national unification and/or liberation from foreign rule. As a result, the period between 1815 and 1871 saw a large number of revolutionary attempts and independence wars. Napoleon III, nephew of Napoleon I, returned from exile in England in 1848 to be elected to the French parliament, and then as "Prince President" in a coup d'état elected himself Emperor, a move approved later by a large majority of the French electorate. He helped in the unification of Italy by fighting the Austrian Empire and fought the Crimean War with England and the Ottoman Empire against Russia. His empire collapsed after an embarrassing defeat for France at the hands of Prussia in which he was captured. France then became a weak republic which refused to negotiate and was finished by Prussia in a few months. In Versailles, King Wilhelm I of Prussia was proclaimed Emperor of Germany, and modern Germany was born. Even though the revolutionaries were often defeated, most European states had become constitutional (rather than absolute) monarchies by 1871, and Germany and Italy had developed into nation states. The 19th century also saw the British Empire emerge as the world's first global power due in a large part to the Industrial Revolution and victory in the Napoleonic Wars.

Empires

The peace would only last until the Ottoman Empire had declined enough to become a target for the others. (See History of the Balkans.) This instigated the Crimean War in 1854 and began a tenser period of minor clashes among the globe-spanning empires of Europe that set the stage for the First World War. It changed a third time with the end of the various wars that turned the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Kingdom of Prussia into the Italian and German nation-states, significantly changing the balance of power in Europe. From 1870, the Bismarkian hegemony on Europe put France in a critical situation. It slowly rebuilt its relationships, seeking alliances with Russia and Britain, to control the growing power of Germany. In this way, two opposing sides formed in Europe, improving their military forces and alliances year-by-year.

War and peace

Apocalypse

After the relative peace of most of the 19th century, the rivalry between European powers exploded in 1914, when World War I started. Over 60 million European soldiers were mobilized from 1914 – 1918. On one side were Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria (the Central Powers/ Triple Alliance), while on the other side stood Serbia and the Triple Entente - the loose coalition of France, the United Kingdom and Russia, which were joined by Italy in 1915 and by the United States in 1917. Despite the defeat of Russia in 1917 (the war was one of the major causes of the Russian Revolution, leading to the formation of the communist Soviet Union), the Entente finally prevailed in the autumn of 1918.

In the Treaty of Versailles (1919) the winners imposed relatively hard conditions on Germany and recognized the new states (such as Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Austria, Yugoslavia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) created in central Europe out of the defunct German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires, supposedly on the basis of national self-determination. Most of those countries engaged in local wars, the largest of them being the Polish-Soviet War (1919-1921). In the following decades, fear of communism and the Great Depression of 1929-1933 led to the rise of extreme nationalist governments – sometimes loosely grouped under the category of fascism – in Italy (1922), Germany (1933), Spain (after a civil war ending in 1939) and other countries such as Hungary.

After allying with Mussolini's Italy in the " Pact of Steel" and signing a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, the German dictator Adolf Hitler started World War II on 1 September 1939 attacking Poland and following a military build-up throughout the late 1930s. After initial successes (mainly the conquest of western Poland, much of Scandinavia, France and the Balkans before 1941) the Axis powers began to over-extend themselves in 1941. Hitler's ideological foes were the Communists in Russia but because of the German failure to defeat the United Kingdom and the Italian failures in North Africa and the Mediterranean the Axis forces were split between garrisoning western Europe and Scandinavia and also attacking Africa. Thus, the attack on the Soviet Union (which together with Germany had partitioned central Europe in 1939-1940) was not pressed with sufficient strength. Despite initial successes, the German army was stopped close to Moscow in December 1941.

Over the next year the tide was turned and the Germans started to suffer a series of defeats, for example in the siege of Stalingrad and at Kursk. Meanwhile, Japan (allied to Germany and Italy since September 1940) attacked the British in Southeast Asia and the United States in Hawaii on December 7, 1941; Germany then completed its over-extension by declaring war on the United States. War raged between the Axis Powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) and the Allied Forces (British Empire, Soviet Union, and the United States). Allied Forces won in North Africa, invaded Italy in 1943, and invaded occupied France in 1944. In the spring of 1945 Germany itself was invaded from the east by the Soviet Union and from the west by the other Allies respectively; Hitler committed suicide and Germany surrendered in early May ending the war in Europe.

This period was marked also by industrialized and planned genocide. Germany began the systematic genocide of over 11 million people, including the majority of the Jews of Europe and Gypsies as well as millions of Polish and Soviet Slavs. Soviet system of forced labour, expulsions and great hunger in Ukraine had similar death toll. During and after the war millions of civilians were affected by forced population transfers.

Cold War

World War I and especially World War II ended the pre-eminent position of western Europe. The map of Europe was redrawn at the Yalta Conference and divided as it became the principal zone of contention in the Cold War between the two power blocs, the Western countries and the Eastern bloc. The United States and Western Europe (the United Kingdom, France, Italy, The Netherlands, West Germany, etc.) established the NATO alliance as a protection against a possible Soviet invasion. Later, the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, East Germany) established the Warsaw Pact as a protection against a possible U.S. invasion.

Meanwhile, Western Europe slowly began a process of political and economic integration, desiring to unite Europe and prevent another war. This process resulted eventually in the development of organizations such as the European Union and the Council of Europe. The Solidarność movement in the 1980s in weakened the Communist government in Poland. The Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev initiated perestroika and glasnost, which weakened Soviet influence in Eastern Europe. Soviet-supported governments collapsed, and West Germany absorbed East Germany by 1990. In 1991 the Soviet Union itself collapsed, splitting into fifteen states, with Russia taking the Soviet Union's seat on the United Nations Security Council. The most violent breakup happened in Yugoslavia, in the Balkans. Four (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia) out of six Yugoslav republics declared independence and for most of them a violent war ensued, in some parts lasting until 1995. In 2006 Montenegro succeeded and became an independent state, followed by Kosovo, formerly an autonomous province of Serbia, in 2008. In the post-Cold War era, NATO and the EU have been gradually admitting most of the former members of the Warsaw Pact.

Reunification and integration

In 1992, the Treaty on European Union was signed by members of the European Union (EU). This transformed the 'European Project' from being the Economic Community with certain political aspects, into the Union of deeper cooperation, and to a greated degree based the pooling of national sovereignty, in politics.

In 1985 the Schengen Agreement created largely open borders without passport controls between those states joining it.

A common currency for most EU member states, the euro, was established electronically in 1999, officially tying all of the currencies of each participating nation to each other. The new currency was put into circulation in 2002 and the old currencies were phased out. Only three countries of the then 15 member states decided not to join the euro (The United Kingdom, Denmark and Sweden). In 2004 the EU undertook a major eastward enlargement, admitting 10 new member states (eight of which were former communist states). Two more joined in 2007, establishing a union of 27 nations.

A treaty establishing a constitution for the EU was signed in Rome in 2004, intended to replace all previous treaties with a new single document. However, it never completed ratification after rejection by French and Dutch voters in referenda. In 2007, it was agreed to replace that proposal with a new Reform Treaty, that would amend rather than replace the existing treaties. This treaty was signed on 13 December 2007, and will come in effect in January 2009 if ratified by that date.

The Balkans are the part of Europe most likely to join the EU next, with Croatia notably hoping to join before 2010.