Parliamentary system

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Politics and government

A parliamentary system, also known as parliamentarianism (and parliamentarism in American English), is a system of government in which the executive is dependent on the direct or indirect support of the legislature (often termed the parliament), often expressed through a vote of confidence.

Parliamentary systems are characterized by no clear-cut separation of powers between the executive and legislative branches, leading to a different set of checks and balances compared to those found in presidential systems. Parliamentary systems usually have a clear differentiation between the head of government and the head of state, with the head of government being the prime minister or premier, and the head of state often being a figurehead, often either a president (elected either popularly or by the parliament) or by a hereditary monarch (often in a constitutional monarchy).

Though in parliamentary systems the prime minister and cabinet will exercise executive power on a day-to-day basis, actual authority will usually be bestowed in the head of state, giving them codified or uncodified reserve powers.

The term parliamentary system does not mean that a country is ruled by different parties in coalition with each other. Such multi-party arrangements are usually the product of an electoral system known as proportional representation. Many parliamentary countries, especially those that use " first past the post" voting, have governments composed of one party. However, parliamentary systems in continental Europe do use proportional representation, and tend to produce election results in which no single party has a majority of seats.

Parliamentarianism may also be for governance in local governments. An example is the city of Oslo, which has an executive council as a part of the parliamentary system. The council-manager system of municipal government used in some U.S. cities bears many similarities to a parliamentary system.

Types

There are broadly two forms of Parliamentary Democracies.

- Westminster System or Westminster Models tend to be found in Commonwealth of Nations countries, although they are not universal within nor exclusive to Commonwealth countries. These parliaments tend to have a more adversarial style of debate and the plenary session of parliament is relatively more important than committees. Some parliaments in this model are elected using " First Past the Post" electoral systems, (e.g. Canada, India and the UK), others using proportional representation, e.g. Ireland and New Zealand. The Australian House of Representatives is elected using the alternative or preferential vote while the Senate is elected using PRSTV (proportional representation through the single transferable vote). However even when proportional representation systems are used, the systems used tend to allow the voter to vote for a named candidate rather than a party list. This model does allow for a greater separation of powers than the Western European Model, although the extent of the separation of powers is nowhere near that of the presidential system of United States.

- Western European Parliamentary Model (e.g., Spain, Germany) tend to have a more consensual debating system, and have semi-cyclical debating chambers. Proportional representation systems are used, where there is more of a tendency to use party list systems than the Westminster Model legislatures. The committees of these Parliaments tend to be more important than the plenary chamber. This model is sometimes called the West German Model since its earliest exemplar in its final form was in the Bundestag of West Germany (which became the Bundestag of Germany upon the absorption of the GDR by the FRG).

There also exists a Hybrid Model, the semi-presidential system, drawing on both presidential systems and parliamentary systems, for example the French Fifth Republic. Much of Eastern Europe has adopted this model since the early 1990s.

Implementations of the parliamentary system can also differ on whether the government needs the explicit approval of the parliament to form, rather than just the absence of its disapproval, and under what conditions (if any) the government has the right to dissolve the parliament. Like Jamaica and many others.

Advantages of a parliamentary system

Some believe that it is easier to pass legislation within a parliamentary system. This is because the executive branch is dependent upon the direct or indirect support of the legislative branch and often includes members of the legislature. Thus, this would amount to the executive (as the majority party or coalition of parties in the legislature) possessing more votes in order to pass legislation. In a presidential system, the executive is often chosen independently from the legislature. If the executive and legislature in such a system include members entirely or predominantly from different political parties, then stalemate can occur. Former US President Bill Clinton often faced problems in this regard, since the Republicans controlled Congress for much of his tenure. Presidents can also face problems from their own parties, however, as former US President Jimmy Carter often did. Accordingly, the executive within a presidential system might not be able to properly implement his or her platform/manifesto. Evidently, an executive in any system (be it parliamentary, presidential or semi-presidential) is chiefly voted into office on the basis of his or her party's platform/manifesto. It could be said then that the will of the people is more easily instituted within a parliamentary system.

In addition to quicker legislative action, Parliamentarianism has attractive features for nations that are ethnically, racially, or ideologically divided. In a unipersonal presidential system, all executive power is concentrated in the president. In a parliamentary system, with a collegial executive, power is more divided. In the 1989 Lebanese Taif Agreement, in order to give Muslims greater political power, Lebanon moved from a semi-presidential system with a strong president to a system more structurally similar to a classical parliamentarianism. Iraq similarly disdained a presidential system out of fears that such a system would be equivalent to Shiite domination; Afghanistan's minorities refused to go along with a presidency as strong as the Pashtuns desired.

It can also be argued that power is more evenly spread out in the power structure of parliamentarianism. The premier seldom tends to have as high importance as a ruling president, and there tends to be a higher focus on voting for a party and its political ideas than voting for an actual person.

In The English Constitution, Walter Bagehot praised parliamentarianism for producing serious debates, for allowing the change in power without an election, and for allowing elections at any time. Bagehot considered the four-year election rule of the United States to be unnatural.

There is also a body of scholarship, associated with Juan Linz, Fred Riggs, Bruce Ackerman, and Robert Dahl that claims that parliamentarianism is less prone to authoritarian collapse. These scholars point out that since World War II, two-thirds of Third World countries establishing parliamentary governments successfully made the transition to democracy. By contrast, no Third World presidential system successfully made the transition to democracy without experiencing coups and other constitutional breakdowns. As Bruce Ackerman says of the 30 countries to have experimented with American checks and balances, "All of them, without exception, have succumbed to the nightmare [of breakdown] one time or another, often repeatedly."

A recent World Bank study found that parliamentary systems are associated with lower corruption.

Criticisms of parliamentarianism

One main criticism of many parliamentary systems is that the head of government is in almost all cases not directly elected. In a presidential system, the president is usually chosen directly by the electorate, or by a set of electors directly chosen by the people, separate from the legislature. However, in a parliamentary system the prime minister is elected by the legislature, often under the strong influence of the party leadership. Thus, a party's candidate for the head of government is usually known before the election, possibly making the election as much about the person as the party behind him or her.

Another major criticism of the parliamentary system lies precisely in its purported advantage: that there is no truly independent body to oppose and veto legislation passed by the parliament, and therefore no substantial check on legislative power. Conversely, because of the lack of inherent separation of powers, some believe that a parliamentary system can place too much power in the executive entity, leading to the feeling that the legislature or judiciary have little scope to administer checks or balances on the executive. However, most parliamentary systems are bicameral, with an upper house designed to check the power of the lower (from which the executive comes).

Although it is possible to have a powerful prime minister, as Britain has, or even a dominant party system, as Japan has, parliamentary systems are also sometimes unstable. Critics point to Israel, Italy, India, the French Fourth Republic, and Weimar Germany as examples of parliamentary systems where unstable coalitions, demanding minority parties, votes of no confidence, and threats of such votes, make or have made effective governance impossible. Defenders of parliamentarianism say that parliamentary instability is the result of proportional representation, political culture, and highly polarised electorates.

Former Prime Minister Ayad Allawi criticized the parliamentary system of Iraq, saying that because of party-based voting "the vast majority of the electorate based their choices on sectarian and ethnic affiliations, not on genuine political platforms."

Although Walter Bagehot praised parliamentarianism for allowing an election to take place at any time, the lack of a definite election calendar can be abused. In some systems, such as the British, a ruling party can schedule elections when it feels that it is likely to do well, and so avoid elections at times of unpopularity. Thus, by wise timing of elections, in a parliamentary system a party can extend its rule for longer than is feasible in a functioning presidential system. This problem can be alleviated somewhat by setting fixed dates for parliamentary elections, as is the case in several of Australia's state parliaments. In other systems, such as the Dutch and the Belgian, the ruling party or coalition has some flexibility in determining the election date.

Alexander Hamilton argued for elections at set intervals as a means of insulating the government from the transient passions of the people, and thereby giving reason the advantage over passion in the accountability of the government to the people.

Critics of parliamentary systems point out that people with significant popular support in the community are prevented from becoming prime minister if they cannot get elected to parliament since there is no option to "run for prime minister" like one can run for president under a presidential system. Additionally, prime ministers may lose their positions solely because they lose their seats in parliament, even though they may still be popular nationally. Supporters of parliamentarianism can respond by saying that as members of parliament, prime ministers are elected firstly to represent their electoral constituents and if they lose their support then consequently they are no longer entitled to be prime minister. In parliamentary systems, the role of the statesman who represents the country as a whole goes to the separate position of head of state, which is generally non-executive and non-partisan. Promising politicians in parliamentary systems likewise are normally preselected for safe seats - ones that are unlikely to be lost at the next election - which allows them to focus instead on their political career.

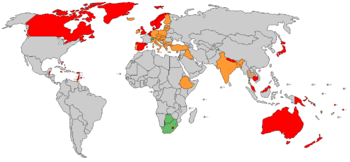

Countries with a parliamentary system of government

Unicameral system

This table shows countries with parliament consisting of a single house.

| Country | Parliament |

|---|---|

| Albania | Kuvendi |

| Bangladesh | Jatiyo Sangshad |

| Bulgaria | National Assembly |

| Burkina Faso | National Assembly |

| Croatia | Sabor |

| Denmark | Folketing |

| Dominica | House of Assembly |

| Estonia | Riigikogu |

| Finland | Eduskunta/Riksdag |

| Greece | Hellenic Parliament |

| Hungary | National Assembly |

| Iceland | Althing |

| Israel | Knesset |

| Latvia | Saeima |

| Lebanon | Assembly of Deputies |

| Lithuania | Seimas |

| Luxembourg | Chamber of Deputies |

| Malta | House of Representatives |

| Moldova | Parliament |

| Mongolia | State Great Khural |

| Montenegro | Parliament |

| New Zealand | Parliament |

| Norway* | Storting |

| Palestinian Authority | Parliament |

| Papua New Guinea | National Parliament |

| Portugal | Assembly of the Republic |

| Republic of Macedonia | Sobranie - Assembly |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | National Assembly |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | House of Assembly |

| Samoa | Fono |

| Serbia | National Assembly |

| Singapore | Parliament |

| Slovakia | National Council |

| Sri Lanka | Parliament |

| Sweden | Riksdag |

| Turkey | Grand National Assembly |

| Ukraine | Verhovna Rada |

| Vanuatu | Parliament |

| Vietnam | National Assembly |

- The Norwegian Parliament is divided in the Lagting and Odelsting in legislative matters. This separation will be abolished with the next parliament in 2009 due to a constitutional amendment.

Bicameral system

This table shows organisations and countries with parliament consisting of two houses.

| Organisation or Country | Parliament | Upper chamber | Lower chamber |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Parliament | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Austria | Parliament | Federal Council | National Council |

| Antigua and Barbuda | Parliament | Senate | House of Representatives |

| The Bahamas | Parliament | Senate | House of Assembly |

| Nigeria | National Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Barbados | Parliament | Senate | House of Assembly |

| Belize | National Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Belgium | Federal Parliament | Senate | Chamber of Representatives |

| Bhutan | Parliament (Chitshog) | National Council (Gyalyong Tshogde) | National Assembly (Gyalyong Tshogdu) |

| Canada | Parliament | Senate | House of Commons |

| Czech Republic | Parliament | Senate | Chamber of Deputies |

| Ethiopia | Federal Parliamentary Assembly | House of Federation | House of People's Representatives |

| European Union | Council of the European Union | European Parliament | |

| Germany | Bundesrat (Federal Council) | Bundestag (Federal Diet) | |

| Grenada | Parliament | Senate | House of Representatives |

| India | Parliament (Sansad) | Rajya Sabha (Council of States) | Lok Sabha (House of People) |

| Ireland | Oireachtas | Seanad Éireann | Dáil Éireann |

| Iraq | National Assembly | Council of Union | Council of Representatives |

| Italy | Parliament | Senate of the Republic | Chamber of Deputies |

| Jamaica | Parliament | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Japan | Diet | House of Councillors | House of Representatives |

| Malaysia | Parliament | Dewan Negara (Senate) | Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives) |

| The Netherlands | States-General | Eerste Kamer | Tweede Kamer |

| Pakistan | Majlis-e-Shoora | Senate | National Assembly |

| Poland | Parliament | Senate | Sejm |

| Romania | Parliament | Senate | Chamber of Deputies |

| The Russian Federation | Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation | Federation Council | Congress of People's Deputies |

| Saint Lucia | Parliament | Senate | House of Assembly |

| Slovenia | Parliament | National Council | National Assembly |

| South Africa | Parliament | National Council of Provinces | National Assembly |

| Spain | Cortes Generales | Senate | Congress of Deputies |

| Switzerland | Federal Assembly | Council of States | National Council |

| Thailand | National Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Trinidad and Tobago | Parliament | Senate | House of Representatives |

| United Kingdom | Parliament | House of Lords | House of Commons |