The Boat Race

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Sports events

The Boat Race is a rowing race in England between the Oxford University Boat Club and the Cambridge University Boat Club. It is rowed annually each spring on the Thames in London. The event is a popular one, not only with the alumni of the universities, but also with rowers in general and the public. An estimated quarter of a million people watch the race live from the banks of the river, around seven to nine million people on TV in the UK, and an overseas audience estimated by the Boat Race Company of around 120 million, however, other estimates put the international audience below 20 million. The first race was in 1829 and it has been held annually since 1856, with the exception of the two world wars.

Members of both teams are traditionally known as blues and each boat as a " Blue Boat", with Cambridge in light blue and Oxford dark blue.

Course

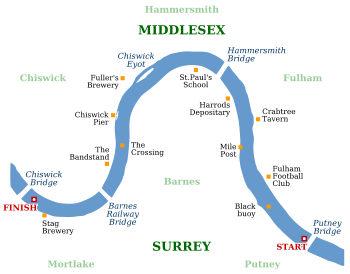

The course is 4 miles and 374 yards (6,779 m) from Putney to Mortlake, passing Hammersmith and Barnes; it is sometimes referred to as the Championship Course, and follows an S shape, east to west. The start and finish are marked by the University Boat Race Stones on the south bank. The clubs' presidents toss a coin (the 1829 sovereign) before the race for the right to choose which side of the river (station) they will row on: their decision is based on the day's weather conditions and how the various bends in the course might favour their crew's pace. The north station (' Middlesex') has the advantage of the first and last bends, and the south (' Surrey') station the longer middle bend.

During the race the coxes compete for the fastest current, which lies at the deepest part of the river, frequently leading to clashes of blades and warnings from the umpire. A crew that gets a lead of more than a boat's length can cut in front of their opponent, making it extremely difficult for the losing crew to overtake back. For this reason the tactics of the race are generally to go fast early on, and few races have a change of the lead after half-way (though this happened in 2003 and again in 2007).

The race is rowed upstream, but is timed to start on the incoming flood tide so that the crews are rowing with the fastest possible current. If a strong wind is blowing from the west it will be against the tide in places along the course, causing the water to become very rough. The conditions are sometimes such that an international regatta would be cancelled, but the Boat Race has a tradition of proceeding even in potential sinking conditions. Several races have featured one, or both, of the crews sinking. This happened to Cambridge in 1859 and 1978, and to Oxford in 1925 and 1951. Both boats sank in 1912, and the race was re-run, and in 1984 Cambridge sank after crashing into a stationary barge while warming up before the race. Cambridge's sinking in 1978 was named in 79th place on Channel 4's list of the 100 Greatest Sporting Moments.

The race is for heavyweight eights (i.e., for eight rowers with a cox steering, and no restrictions on weight). Female coxes are permitted, the first to appear in the Boat Race being Sue Brown for Oxford in 1981. In fact female rowers would be permitted in the men's boat race, though the reverse is not true.

During the race the crews pass various traditional landmarks, visible from the river:

| Landmark | Coordinates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Oxford boats from Westminster School Boat Club (left), and Cambridge from King's College School Boat Club (right). Both clubs are near the Start, just downstream of the Black Buoy. | |

|

|

The University Stone lies on the south bank. The winner of the toss chooses their station (the Surrey station has won 10 out of the last 15 races). In the straight section after the start the Middlesex crew tries to hold the fastest water on the centre line of the river. | |

|

|

Roughly marks the end of the Putney Boat Houses. The Black Buoy has now been painted yellow to avoid collisions. | |

|

|

'Craven Cottage': crews stay wide (preferring the Surrey bank) round the bend as the area in front of the football ground (known as 'the Fulham flats') is shallow, with slack water.. | |

|

|

Marked by a bust of Steve Fairbairn. A traditional timing point in the Boat Race. The Middlesex bank water continues to be shallow and slack all the way to Hammersmith Bridge. | |

|

|

This section is called the "Crabtree Reach" after the Crabtree Tavern pub on the Middlesex bank (just to the right of the camera). | |

|

|

Previously the warehouse for the famous shop, now apartments. For the next 8-9 minutes the bend will be in Surrey's favour. The deep water channel now lies close to the Surrey bank. | |

|

|

Coxes aim for the second lamp-post from the left which marks the deepest part of the river and therefore the fastest line. 80%-85% of boats ahead at Hammersmith Bridge have won, though only 50% in the last 6 years. The turning point comes once the crews are under Hammersmith Bridge. | |

|

|

1.80 miles have been rowed and the direction and perhaps the wind and water conditions are about to change. The next 3-4 minutes are Surrey's last major opportunity to kill the Middlesex crew off. | |

|

|

An uninhabited river island. The river is straight again, and the deepest water is half-way between the Eyot and the Surrey bank. | |

|

|

Just visible to crews, behind the eyot. The most exposed section of the course with the risk of wind problems. | |

|

|

2.87 miles have been rowed. If there are wind problems the inside of the Middlesex bend may offer calmer water. | |

|

|

Marks the end of the long Surrey bend. The deep water channel is in the centre of the river. | |

|

|

The deep water channel lies close to the Middlesex bank at this point, and water near the Surrey bank is shallow. | |

|

|

Crews must pass through the centre arch. 95% of boats leading here have won. Only one boat has won since 1945 when trailing at Barnes Bridge: Oxford came from behind this late in 2002. The Barnes Bridge corner is very tight: if both crews are level this is a real test for the coxes. | |

|

|

3.94 miles have been rowed. Previously a Watneys brewery, now producing Budweiser beer. | |

|

|

The finish, just before Chiswick Bridge is marked by a stone on the south bank and a post on the north bank. |

In the arms of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, which covers much of the course, two griffin supporters hold oars, one light blue, one dark, in reference to the Boat Race. These colours are highly unusual in English heraldry.

Previous Courses

The course for the main part of the races' history has been from Putney to Mortlake, but there have three other courses:

- 1829 — At Henley-on-Thames

- 1839 to 1842 — Westminster to Putney

- 1846, 1856, 1862, 1863 — Mortlake to Putney

In addition, there were four unofficial boat races held during World War II away from London — 1940 (Henley-on-Thames), 1943 ( Sandford-on-Thames), 1944 ( River Great Ouse, Ely), and 1945. As none of those competing were awarded blues, these races are not included in the official list.

History

The tradition was started in 1829 by Charles Merivale, a student at St John's College, Cambridge, and his schoolfriend Charles Wordsworth who was at Oxford. Cambridge challenged Oxford to a race, and the challenge was repeated the next year. The tradition continues, with the loser challenging the winner to a re-match annually.

The race in 1877 was declared a dead heat. Legend in Oxford has it that the judge, "Honest John" Phelps, was asleep under a bush as the crews came by leading him to announce the result as a "dead heat to Oxford by four feet", but this is not borne out by contemporary reports. The Times said:

Oxford, partially disabled, were making effort after effort to hold their rapidly waning lead, while Cambridge, who, curiously enough, had settled together again, and were rowing almost as one man, were putting on a magnificent spurt at 40 strokes to the minute, with a view of catching their opponents before reaching the winning-post. Thus struggling over the remaining portion of the course, the two eights raced past the flag alongside one another, and the gun fired amid a scene of excitement rarely equalled and never exceeded. Cheers for one crew were succeeded by counter-cheers for the other, and it was impossible to tell what the result was until the Press boat backed down to the Judge and inquired the issue. John Phelps, the waterman, who officiated, replied that the noses of the boats passed the post strictly level, and that the result was a dead heat.

The Competitors

Although the contest is strictly between amateurs and the competitors must be students of the university for whom they race, the training schedules each team undertakes are very gruelling. Typically each team trains for six days a week for six months before the event.

Such is the competitive spirit between the universities it is common for Olympic standard rowers to compete, notably including four times Olympic gold medallist Matthew Pinsent who rowed for Oxford in 1990, 1991, and 1993. Olympic Gold medallists from 2000 - Tim Foster (Oxford 1997), Luka Grubor (Oxford 1997), Andrew Lindsay (Oxford 1997, 1998, 1999) and Kieran West (Cambridge 1999, 2001, 2006, 2007) - and 2004 - Ed Coode (Oxford 1998) have also raced for their university. Other famous participants in the race include Andrew Irvine (Oxford 1923), Lord Snowdon (Cambridge 1950), David Rendel (Oxford 1974), Colin Moynihan (Oxford 1977), and Hugh Laurie (Cambridge 1980).

Academic Status

There are no sporting scholarships at Oxford or Cambridge, so in theory every student must obtain a place at their university on their academic merits, but there have been unproven accusations that these students are admitted to the universities for their rowing skill without meeting the normal academic standards.

From 1978 to 1983 the race was won every year by Oxford crews that included Boris Rankov, who was then a graduate student at Oxford and recognised as a powerhouse of the crews. Although Rankov was a bona fide student (and is now a professor at the University of London), this led to the establishment of the informal 'Rankov Rule', to which the teams have adhered ever since, that no rower may compete in the boat race more than four times as an undergraduate, and four times as a graduate.

In order to protect the status of the race as a competition between genuine students, the Boat Race organising committee in July 2007 refused to award a blue to 2006 and 2007 Cambridge oarsman Thorsten Engelmann, as he did not complete his academic course and instead returned to the German national rowing team to prepare for the Beijing Olympics. This has caused a debate about a change of rules, and one suggestion appears to be that only students that are enrolled in courses lasting at least two years should be eligible to race.

Evidence suggests that participants in the boat race are indeed academically capable: the 2005 Cambridge crew, for example, contained four Ph.D students, including a fully qualified medical doctor and a veterinarian.

Standard of the Crews

The question whether the Boat Race crews are up to the standard of international crews is difficult to judge, since the Boat Race crews train for a long-distance race early in the season, so their training schedule is quite different for crews training for international regattas over 2000 metres that take place later in the year.

The Boat Race crews do race against selected club and international crews in the build-up to the race, and are competitive against them, but again these matches are over various non-standard distances, against crews that might not have been together as long as the Oxbridge crews.

In 2007 Cambridge were entered in the London Head of the River Race where they should have been measured directly against the best crews in Britain and beyond. However, the event was called off after several crews were sunk or swamped in rough conditions. Cambridge were fastest of the few crews who did manage to complete the course.

Sponsorship

The Boat Race has been sponsored since 1976, with the money spent mainly on equipment and travel during the training period and some being passed to the womens' and lightweight rowing clubs. The sponsors do not have their logos on the boats or kit during the race, but provide branded training gear and have some naming rights. Boat Race sponsors have included Ladbrokes, Beefeater Gin, Aberdeen Asset Management, and Xchanging, who will sponsor the race until 2012. In a renewal of the deal with Xchanging, the crews have agreed to wear the sponsor's logo on their kit during the race, in exchange for increased funding.

Oxford Mutinies

There have been two instances where oarsmen have rebelled against the leadership of the Boat Club President and their coach. Both have involved Oxford University Boat Club and in both cases American oarsmen played a pivotal role.

1959

Oxford in Autumn 1958 had a large and talented squad. It included eleven returning Blues plus Yale oarsmen Reed Rubin and Charlie Grimes, a gold medallist at the 1956 Olympics. Ronnie Howard was elected OUBC President by the College Captains, beating Rubin. In 1958, Howard had rowed in the Isis crew coached by H.R.A. "Jumbo" Edwards, which had frequently beaten the Blue Boat in training.

Howard's first act was to appoint Edwards as coach. Edwards was a coach with a strong record, but he also imposed strict standards of obedience, behaviour and dress on the triallists which many of them found childish. As an example, Grimes withdrew from the squad after Edwards insisted he remove his "locomotive driver's hat" in training.

With selection for the crew highly competitive, the squad split along the lines of the presidential election. A group of dissidents called a press conference, announcing that they wanted to form a separate crew, led by Rubin and with a different coach. They then wished to race off with Howard's crew to decide who would face Cambridge.

Faced with this challenge, Ronnie Howard returned to the College Captains and asked for a vote of confidence in his selected crew and the decision not to race off with the Rubin crew. He won the vote decisively and the Cambridge president also declared that his crew would only race the Howard eight.

Three of the dissidents returned and Oxford went on to win by six lengths.

1987

In 1987, another disagreement arose amongst the Oxford team. A number of top class American oarsmen refused to row when a fellow American was dropped in preference for the Scottish President, Donald Macdonald. They became embroiled in a conflict with Macdonald and with coach Dan Topolski over his training and selection methods. This eventually led most of the Americans to protest what they perceived to be the president's abuse of power, by withdrawing six weeks before the race was due to start. As Gavin Stewart, the stroke and mainstay of the winning Oxford eight, stated:

As for the Americans starting the 'mutiny', well they didn't. The 'mutiny' happened because the squad had lost respect for Donald Macdonald as president, not least because he made it clear that he had a guaranteed seat... The spark was the decision to set aside the result of a trial between Macdonald and one of the Americans (which Macdonald lost), giving them both seats and dropping another (British) rower. The Americans began by supporting British rowers, not the other way round.

To the surprise of many, Oxford, with a crew partially composed of oarsmen from the reserve team, went on to win the race. One aspect of the race was Topolski's tactic, communicated to the cox while the crews were on the start, for Oxford to take shelter from the rough water in the middle of the river at the start of the race, ignoring conventional wisdom that centre stream is fastest even if rowing conditions are poor.

A further surprise was that the captains of the Oxford college boat clubs, who had voted in support of Macdonald and Topolski and precipitated the Americans' withdrawal during the mutiny, voted one of those Americans, Chris Penney, as OUBC president for 1988, a break with the tradition that the president is a returning Blue (the other candidate being Tom Cadoux-Hudson, who was a British member of the 1987 winning crew).

Topolski wrote a book entitled True Blue: The Oxford Boat Race Mutiny on the incident. A movie based on the book, True Blue, was released in 1996. Topolski's account was seen by some as one-sided, and Ali Gill, who had been a member of the university women's Boat Club at the time of the mutiny, wrote a book The Yanks at Oxford to put the other side of the story.

Reported facts of the "mutiny" still differ greatly depending on the source, and with the historians having been personally involved in the events or the small community in which they occurred, a definitive, unbiased version has never been agreed upon. Macdonald and the Americans have refused to contribute to any debate on the event, including a 2007 BBC radio programme to mark the 20th anniversary.

Recent Years

Recent years have seen especially dramatic races. In 2002, the favoured Cambridge crew led with only a few hundred metres to go, when a Cambridge oarsman ( Sebastian Mayer) collapsed from exhaustion and Oxford rowed through to win by three-quarters of a length. They did so on the outside of the last river bend, a feat last accomplished in 1952. Few observers expected the 2003 race to match the 2002 for excitement. Cambridge were substantially heavier and appeared to be the favourites. Two days prior to the race, however, the Cambridge crew suffered a collision on the river in which oarsman Wayne Pommen was injured. With a replacement in Pommen's seat, Cambridge went on to lose to a determined Oxford crew by a record slim margin of one foot. In that year, there were two sets of brothers rowing: Matt Smith and David Livingston for Oxford, and Ben Smith and James Livingston for Cambridge. All four had been pupils together at Hampton School in south-west London. Cambridge gained revenge in 2004 in a race marred by dramatic clashes of oars in the early stages, and the unseating of Oxford's bowman.

The 2006 race was won by Oxford, despite Cambridge having started as strong favourites. Despite rough rain, Cambridge had made a tactical decision not to use a pump to remove excess water in the boat. Oxford did use a pump and overtook Cambridge to win. Cambridge had in fact introduced pumps as early as 1987 (the year of the Oxford mutiny, and a day of rough conditions).

In 2007 Cambridge were strong favourites based on the team members' individual successes, and 9 lb heavier per man on average. The Cambridge crew had five returning blues compared to Oxford's one. Furthermore, the international achievement of Cambridge's rowers far exceeded that of Oxford's: the World Champion stern pair of Germans Thorsten Engelmann (the heaviest ever boat race oarsman at 110.4 kg) and Sebastian Schulte; Olympic Gold medallist Kieran West MBE and GB medal winner Tom James.

Although Oxford rowed strongly as underdogs at the beginning, the light blues showed their class by holding Oxford while they had the advantage, and pushing on with tidier rowing from Chiswick steps. They rowed on to win by a length and a quarter in a time of 17 minutes and 49 seconds. The heavily-fancied Cambridge crew did not win by the margin expected by many, thanks in part to a strong row from Oxford.

It was speculated by 2006 Oxford winning president Barney Williams that the race was won by Cambridge while Oxford still had their lead. Around Hammersmith Bridge the Cambridge crew (with their backs to Oxford) had no view of their rivals and the calm orders delivered from Cambridge coxswain Rebecca Dowbiggin "they're throwing the kitchen sink at this boys", and "keep loose, loose, loose..." ensured that they stayed in contention despite a push from Oxford going into Hammersmith. Beyond this point the advantage of the Surrey station to Oxford had been lost and the race was Cambridge's.

Other Oxford/Cambridge Boat Races

Although the heavyweight men's eights are the main draw, the two universities compete in other rowing boat races. The main boat race is preceded by a race between the two reserve crews (called Isis for Oxford and Goldie for Cambridge), which in 2008 was won by Isis.

The women's eights, women's reserve eights, men's lightweight eights, men's lightweight reserve eights, and women's lightweight eights race in the Henley Boat Races a week before the men's heavyweight races.

Build-up

Training for the boat race officially begins in September, before the start of term. The first tests are in November at the British Indoor Rowing Championships where each university sends around 20 rowers to compete. Everyone races 2 km on an indoor rower with the club presidents using adjacent machines. Both universities also send crews to the Head of the River Fours race in London which is raced over the reverse Boat Race course, that is to say the Championship course from Mortlake to Putney.

In December, the coaches put out Trial Eights where two crews from the same university race each other over the full boat race course. These crews are given names such as Kara and Whakamanawa (Māori words for strength and honour, Cambridge 2004) or Cowboys and Indians (Oxford 2004).

Over the Christmas period the squads go on training camps abroad, where final places for the blue boats are decided. After the final blue boat crews have been decided they race against the top crews from the UK and abroad (e.g. in recent years they have raced Leander, Molesey, and the German international crew). These races are only over part of the course (from Putney to Chiswick Eyot).

In case of injury or illness, each university has ten extra rowers, eight in the reserve boats Isis and Goldie, and two as the spare pair. Isis and Goldie race 30 mins before the Blue Boat event over the same course. As for the spare pair, in the week before the main event they race each other from the mile post to university stone (i.e. from a point one mile into the Championship Course back to the Boat Race start). In the final week, there is also an official weigh in and the average crew weights announced. The perceived slight advantage of being the heavier crew leads to the practice of drinking large volumes of water directly before the weigh in order to artificially increase weight for a short period of time.

Popular Culture

"Boat race" became such a popular phrase that it was incorporated into Cockney rhyming slang, for "face".

Results

Overall Race Wins

- Cambridge: 79 wins

- Oxford: 74 wins

- Dead heats: 1

Reserve Race

- Cambridge (Goldie): 28 wins

- Oxford (Isis): 16 wins

Unofficial wartime races

| Date | Location | Winner |

|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Henley-on-Thames | Cambridge |

| 1943 | Sandford-on-Thames | Oxford |

| 1944 | River Great Ouse, Ely | Oxford |

| 1945 | Unknown | Cambridge |

Full Results by Year

Statistics

|