Theropoda

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Dinosaurs

| Theropods Fossil range: Late Triassic - Late Cretaceous (excluding birds) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tyrannosaurus foot

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Infraorders | ||||||||||||

|

Theropods (pronounced /ˈθɪərəpɒd/, theropoda /θiːˈrɒpədə/ 'beast feet') are a group of bipedal saurischian dinosaurs. Although they were primarily carnivorous, a number of theropod families evolved herbivory during the Cretaceous Period. Theropods first appear during the Carnian age of the Late Triassic about 220 million years ago ( MYA) and were the sole large terrestrial carnivores from the Early Jurassic until the close of the Cretaceous, about 65 MYA. Today, they are represented by the 9,300 living species of birds, which evolved in the Late Jurassic from small specialized coelurosaurian dinosaurs.

Among the features linking theropods to birds are the three-toed foot, a furcula (wishbone), air-filled bones and (in some cases) feathers and brooding of the eggs.

Evolutionary history

During the late Triassic, a number of primitive proto-theropod and theropod dinosaurs existed and evolved alongside each other.

The earliest and most primitive of the carnivorous dinosaurs were Eoraptor of Argentina and the herrerasaurs. The herrerasaurs existed from the early late Triassic (Late Carnian to Early Norian). They were found in North America and South America and possibly also India and Southern Africa. The herrerasaurs were characterised by a mosaic of primitive and advanced features. Some paleontologists have in the past considered the herrerasaurians to be members of Theropoda, though they are now thought to be basal saurischians, and may even have evolved prior to the saurischian-ornithischian split.

The earliest and most primitive unambiguous theropods (or alternatively, Eutheropoda - 'True Theropods') are the Coelophysidae. The Coelophysidae ( Coelophysis, Megapnosaurus) were a group of widely distributed, lightly built and apparently gregarious animals. They included small hunters like Coelophysis and larger (6 meters) predators like Dilophosaurus. These successful animals continued from the Late Carnian (early Late Triassic) through to the Toarcian (late Early Jurassic). Although in the early cladistic classifications they were included under the Ceratosauria and considered a side-branch of more advanced theropods, they may have been ancestral to all other theropods (which would make them a paraphyletic group.

The somewhat more advanced true Ceratosauria (including Ceratosaurus and Carnotaurus) appeared during the Early Jurassic and continued through to the Late Jurassic in Laurasia. They competed quite well alongside their more advanced tetanuran relatives and - in the form of the abelisaur lineage - lasted to the end of the Cretaceous in Gondwana.

The Tetanurae are more specialised again than the Ceratosaurs. They are subdivided into Megalosauroidea (alternately Spinosauroidea or Torvosauroidea) and the Avetheropoda. They were most common during the Middle Jurassic but continued to the Middle Cretaceous. The latter clade - as their name indicates - were more closely related to birds and are again divided into the Carnosauria (including Allosaurus) and the Coelurosauria, a very large and diverse dinosaur group that was especially common during the Cretaceous.

Thus, during the late Jurassic, there were no fewer than four distinct lineages of theropods - ceratosaurs, megalosaurs, carnosaurs, and coelurosaurs - preying on the abundance of small and large herbivorous dinosaurs. All four groups survived into the Cretaceous, although only two - the abelisaurs and the coelurosaurs - seem to have made it to end of the period, where they were geographically separate, the abelisaurs in Gondwana, and the coelurosaurs in Asiamerica.

Of all the theropod groups, the coelurosaurs were by far the most diverse. Some coelurosaur clades that flourished during the Cretaceous were the tyrannosaurids (including Tyrannosaurus) the dromaeosaurids (including Velociraptor and Deinonychus, which are remarkably similar in form to the oldest known bird, Archaeopteryx), the bird-like troodontids and oviraptorosaurs, the ornithomimosaurs (or "ostrich dinosaurs"), the strange giant-clawed herbivorous Therizinosauridae, and the birds, which are the only dinosaur lineage to survive the end Cretaceous mass-extinction. While the roots of these various groups must have been in the Late or possibly even the Middle Jurassic, they only became abundant during the Early Cretaceous. A few paleontologists, such as Gregory S. Paul, have suggested that some or all of these advanced theropods were actually descended from flying dinosaurs or proto-birds like Archaeopteryx that lost the ability to fly and returned to a terrestrial habitat.

Classification

History of classification

The name Theropoda (meaning "beast feet") was first coined by O.C. Marsh in 1881. Marsh initially named Theropoda as a suborder to include the family Allosauridae, but later expanded its scope, re-ranking it as an order to include a wide array of "carnivorous" dinosaur families, including Megalosauridae, Compsognathidae, Ornithomimidae, Plateosauridae and Anchisauridae (now known to be herbivorous prosauropods) and Hallopodidae (now known to be relatives of crocodilians). Due to the scope of Marsh's Order Theropoda, it came to replace a previous taxonomic group that Marsh's rival E.D. Cope had created in 1866 for the carnivorous dinosaurs, Goniopoda ("angled feet").

By the early 20th Century, some paleontologists, such as Friedrich von Huene, no longer considered carnivorous dinosaurs to have formed a natural group. Huene abandoned the name Theropoda, instead using Harry Seeley's Order Saurischia, which Huene divided into the suborders Coelurosauria and Pachypodosauria. Huene placed most of the small theropod groups into Coelurosauria, and the large theropods and prosauropods into Pachypodosauria, which he considered ancestral to the Sauropoda (prosauropods were still thought of as carnivorous at this time, owing to the incorrect association of rauisuchian skulls and teeth with prosauropod bodies, in animals such as Teratosaurus). In W.D. Matthew and Barnum Brown's 1922 description of the first known dromaeosaurid ( Dromaeosaurus albertensis), they became the first paleontologists to exclude prosauropods from the carnivorous dinosaurs, and attempted to revive the name Goniopoda for that group, though neither of these suggestions were accepted by other scientists.

It was not until 1956 that Theropoda came back into use as a taxon containing the carnivorous dinosaurs and their descendants, when Alfred Romer re-classified the Order Saurischia into two suborders, Theropoda and Sauropoda. This basic division has survived into modern paleontology, with the exception of, again, the Prosauropoda, which Romer included as an infraorder of theropods. Romer also maintained a division between Coelurosauria and Carnosauria (which he also ranked as infraorders). This dichotomy was upset by the discovery of Deinonychus and Deinocheirus in 1969, neither of which could be classified easily as "carnosaurs" or "coelurosaurs." In light of these and other discoveries, by the late 1970s Rinchen Barsbold created a new series of theropod infraorders: Coelurosauria, Deinonychosauria, Oviraptorosauria, Carnosauria, Ornithomimosauria, and Deinocheirosauria.

With the advent of cladistics and phylogenetic nomenclature in the 1980s, and their development in the 1990s and 2000s, a clearer picture of theropod relationships began to emerge. Several major theropod groups were named by Jacques Gauthier in 1986, including the clade Tetanurae for one branch of a basic theropod split with another group, the Ceratosauria. As more information about the link between dinosaurs and birds came to light, the more bird-like theropods were grouped in the clade Maniraptora (also named by Gauthier in 1986). These new developments also came with a recognition among most scientists that birds arose directly from maniraptoran theropods and, with the abandonment of ranks in cladistic classification, the re-evaluation of birds as a subset of theropod dinosaurs that happened to have survived the Mesozoic extinctions into the present.

Taxonomy

- Suborder Theropoda

- Agnosphitys

- Chindesaurus

- Guaibasaurus

- Infraorder Ceratosauria

- Family Ceratosauridae

- Superfamily Abelisauroidea

- Superfamily Coelophysoidea

- Clade Tetanurae

- Superfamily Spinosauroidea

- Infraorder Carnosauria

- Superfamily Allosauroidea

- Clade Coelurosauria

- Family Coeluridae

- Family Compsognathidae

- Superfamily Tyrannosauroidea

- Infraorder Ornithomimosauria

- Clade Maniraptora

- Family Scansoriopterygidae

- Superfamily Therizinosauroidea

- Infraorder Deinonychosauria

- Family Dromaeosauridae

- Family Troodontidae

- Infraorder Oviraptorosauria

Phylogeny

The following cladogram is adapted from Weishampel et al., 2004.

| Theropoda |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Size

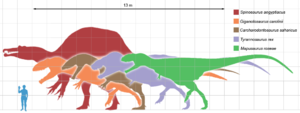

Tyrannosaurus was the largest and most popular theropod known to the general public for many decades. Since its discovery, however, a number of other giant carnivorous dinosaurs have been described, including Spinosaurus, Carcharodontosaurus, Giganotosaurus, Tyrannotitan and Mapusaurus.The original Spinosaurus specimens (as well as newer fossils described in 2006) support the idea that Spinosaurus is larger than Tyrannosaurus, showing that Spinosaurus was possibly 6 meters longer and at least 1 metric ton heavier than Tyrannosaurus. There is still no clear scientific explanation for exactly why these animals grew so much larger than the predators that came before and after them. Parallel to this, the smallest known theropod is the bee hummingbird.