History of Alaska

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: North American History

|

| History of Alaska |

|---|

| Prehistory |

| Russian Alaska (1733-1867) |

| Department of Alaska (1867-1884) |

| District of Alaska (1884-1912) |

| Alaska Territory (1912-1959) |

| Recent history (1959-present) |

| Other topics |

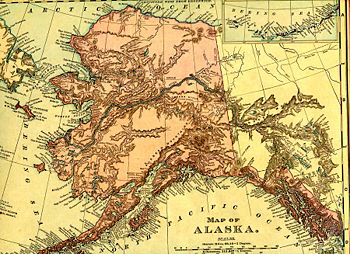

The history of Alaska dates back to the end of the Upper Paleolithic Period (around 12,000 BC), when Asiatic groups crossed the Bering Land Bridge into what is now western Alaska. At the time of European contact by the Russian explorers, the area was populated by Alaska Native groups. The name "Alaska" derives from the Aleut word alaxsxaq, (an Archaic spelling being alyeska), meaning "mainland" (literally, "the object toward which the action of the sea is directed").

The first European contact with Alaska occurred in 1741, when Vitus Bering led an expedition for the Russian Navy aboard the St. Peter. After his crew returned to Russia bearing sea otter pelts judged to be the finest fur in the world, small associations of fur traders began to sail from the shores of Siberia towards the Aleutian islands. The first permanent European settlement was founded in 1784, and the Russian-America Company carried out expanded colonization program during the early to mid-1800s. Despite these efforts, the Russians never fully colonized Alaska, and the colony was never very profitable. William H. Seward, the U.S. Secretary of State, engineered the Alaskan purchase in 1867 for $7.2 million.

In the 1890s, gold rushes in Alaska and the nearby Yukon Territory brought thousands of miners and settlers to Alaska. Alaska was granted territorial status in 1912.

In 1942, three of the outer Aleutian Islands—Attu, Agattu and Kiska—were occupied by the Japanese and their recovery for the U. S. became a matter of national pride. The construction of military bases contributed to the population growth of some Alaskan cities.

Alaska was granted statehood on January 3, 1959.

In 1964, the massive " Good Friday Earthquake" killed 131 people and leveled several villages.

The 1968 discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay and the 1977 completion of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline led to an oil boom. In 1989, the Exxon Valdez hit a reef in the Prince William Sound, spilling between 11 and 35 million US gallons (42,000 and 130,000 m³) of crude oil over 1,100 miles (1,600 km) of coastline. Today, the battle between philosophies of development and conservation is seen in the contentious debate over oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Prehistory

Paleolithic families moved into northwestern North America sometime between 16,000 and 10,000 BC across the Bering Land Bridge in western Alaska. Alaska became populated by the Inuit and a variety of Native American groups. Today, early Alaskans are divided into several main groups: the Southeastern Coastal Indians (the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian), the Athabascans, the Aleut, and the two groups of Eskimos, the Inupiat and the Yup'ik.

The Coastal asians were probably the first wave of immigrants to cross the Bering Land Bridge in western Alaska, and many of them initially settled in interior Canada. The Tlingit were the most numerous of this group, claiming most of the coastal Panhandle by the time of European contact. The southern portion of Prince of Wales Island was settled by the Haidas emigrating from the Queen Charlotte Islands in Canada. The Aleuts settled the islands of the Aleutian chain approximately 10,000 years ago.

Cultural and subsistence practices varied widely among Native groups, who were spread across vast geographical distances.

18th century

European discovery

The first European contact with Alaska came as a part of the 1733-1743 second Kamchatka expedition, after the St. Peter (captained by Dane Vitus Bering) and the St. Paul (captained by his deputy, Russian Alexei Chirikov) set sail from Russia in June 1741. On July 15, Chirikov sighted land, probably the west side of Prince of Wales Island in Southeast Alaska. He sent a group of men ashore in a long boat, making them the first Europeans to land on the northwestern coast of North America. Bering and his crew sighted Mt. St. Elias. Chirikov and Bering's crew returned to Russia in 1742, carrying word of the expedition. The sea otter pelts they brought, soon judged to be the finest fur in the world, would spark Russian settlement in Alaska.

Early Russian settlement

After the second Kamchatka expedition, small associations of fur traders began to sail from the shores of Siberia towards the Aleutian islands. As the runs from Siberia to America became longer expeditions, the crews established hunting and trading posts. By the late 1790s, these had become permanent settlements.

On some islands and parts of the Alaska Peninsula, groups of traders had been capable of relatively peaceful coexistence with the local inhabitants. Other groups could not manage the tensions and perpetrated exactions. Hostages were taken, individuals were enslaved, families were split up, and other individuals were forced to leave their villages and settle elsewhere. Over the years, the situation became catastrophic. Eighty percent of the Aleut population was destroyed by Old World diseases, against which they had no immunity, during the first two generations of Russian contact.

Though the colony was never very profitable, most Russian traders were determined to keep the land. In 1784, Grigory Ivanovich Shelikhov arrived in Three Saints Bay on Kodiak Island. Shelikov established Russian dominance on the island by killing hundreds of indigenous Koniag, then founded the first permanent Russian settlement in Alaska on the island's Three Saints Bay.

In 1790, Shelikhov hired Alexandr Baranov to manage his Alaskan fur enterprise. Baranov moved the colony to what is now the city of Kodiak. In 1795, Baranov, concerned by the sight of non-Russian Europeans trading with the Natives in southeast Alaska, established Mikhailovsk near present-day Sitka. Though he bought the land from the Tlingits, Tlingits from a neighboring settlement later attacked and destroyed Mikhailovsk. After Baranov retaliated, razing the Tlingit village, he built the settlement of New Archangel. It became the capital of Russian America and today is the city of Sitka.

Missionary activity

The Russian Orthodox religion (with its rituals and sacred texts, translated into Aleut at a very early stage) had been informally introduced, in the 1740s-1780s, by the fur traders. During his settlement of Three Saints Bay in 1784, Shelikov introduced the first resident missionaries and clergymen. This missionary activity would continue into the 1800s, ultimately becoming the most visible trace of the Russian colonial period in contemporary Alaska.

Spain's attempts at colonization

Spanish claims to Alaska dated to the papal bull of 1493, which allocated to the Spanish the right to colonize the west coast of North America. When rival countries, including Britain and Russia, began to show interest in Alaska in the late 18th century, King Charles III of Spain sent a number of expeditions to re-assert Spanish claims to the northern Pacific Coast of North America, including Alaska.

In 1775, Bruno de Hezeta led an expedition designed to solidify Spanish claims to the northern Pacific. One of the expedition's two ships, the Señora, ultimately reached 59°N latitude, entering Sitka Sound near the present-day town of Sitka, Alaska. There, the Spaniards performed numerous "acts of sovereignty," naming and claiming Puerto de Bucareli ( Bucareli Sound), Puerto de los Remedios, and Mount San Jacinto, renamed Mount Edgecumbe by British explorer James Cook three years later.

In 1790, Spanish explorer Salvador Fidalgo led an expedition that included visits to the sites of today's Cordova, Alaska and Valdez, Alaska, where acts of sovereignty were performed. Fidalgo went as far as today's Kodiak Island, visiting the small Russian settlement there. Fidalgo then went to the Russian settlement at Alexandrovsk (today's English Bay or Nanwalek, Alaska), southwest of today's Anchorage on the Kenai Peninsula, where again, Fidalgo re-asserted the Spanish claim to the area by conducting a formal ceremony of sovereignty.

In 1791, Alessandro Malaspina undertook an around-the-world scientific expedition, with orders to locate the Northwest Passage and search for gold, precious stones, and any American, British, or Russian settlements along the northwest coast. He surveyed the Alaska coast to the Prince William Sound. At Yakutat Bay, the expedition made contact with the Tlingit.

In the end, the North Pacific rivalry proved to be too difficult for Spain, which withdrew from the contest and transferred its claims in the region to the United States in the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819. Today, Spain's Alaskan legacy endures as little more than a few place names, among these the Malaspina Glacier and the town of Valdez.

Britain's presence

British settlements in Alaska consisted of a few scattered trading outposts, with most settlers arriving by sea. Captain James Cook, midway through his third and final voyage of exploration in 1778, sailed along the west coast of North America aboard the HMS Resolution, mapping the coast from the state of California all the way to the Bering Strait. During the trip, he discovered what came to be known as Cook Inlet (named in honour of Cook in 1794 by George Vancouver, who had served under his command) in Alaska. The Bering Strait proved to be impassable, although the Resolution and its companion ship HMS Discovery made several attempts to sail through it. The ships left the straits to return to Hawaii in 1779.

Cook's expedition spurred the British to increase their sailings along the northwest coast, following in the wake of the Spanish. Three Alaska-based posts, funded by the Hudson's Bay Company, operated at Fort Yukon, on the Stikine River, and in Wrangell (the only Alaskan town to have been the subject of British, Russian, and American rule) throughout the early 1800s.

19th century

Later Russian settlement and the Russian-American Company (1799-1867)

In 1799, Shelikhov's son-in-law, Nikolay Petrovich Rezanov, acquired a monopoly on the American fur trade from Czar Paul I and formed the Russian-American Company. As part of the deal, the Tsar expected the company to establish new settlements in Alaska and carry out an expanded colonization program.

By 1804, Alexandr Baranov, now manager of the Russian–American Company, had consolidated the company's hold on the American fur trade following his victory over the local Tlingit clan at the Battle of Sitka. Despite these efforts, the Russians never fully colonized Alaska. The Russian monopoly on trade was also being weakened by the Hudson's Bay Company, which set up a post on the southern edge of Russian America in 1833.

American hunters and trappers, who encroached on territory claimed by Russians, were also becoming a force. An 1812 settlement giving Americans the right to the fur trade only below 55°N latitude was widely ignored, and the Russians' hold on Alaska weakened further.

The Russian-American Company suffered because of 1821 amendments to its charter, and eventually it entered into an agreement with the Hudson's Bay Company that allowed the British to sail through Russian territory.

At the height of Russian America, the Russian population reached 700.

Although the mid–1800s were not a good time for Russians in Alaska, conditions improved for the coastal Alaska Natives who had survived contact. The Tlingits were never conquered and continued to wage war on the Russians into the 1850s. The Aleuts, though faced with a decreasing population in the 1840s, ultimately rebounded.

Alaska purchase

Financial difficulties in Russia, the desire to keep Alaska out of British hands, and the low profits of trade with Alaskan settlements all contributed to Russia's willingness to sell its possessions in North America. At the instigation of U.S. Secretary of State William Seward, the United States Senate approved the purchase of Alaska from Russia for $7,200,000. (approximately $90,750,000 in 2005 dollars, adjusted for inflation) on 9 April 1867. This purchase was popularly known in the U.S. as "Seward's Folly", or "Seward's Icebox", and was unpopular at the time, though the later discovery of gold and oil would show it to be a worthy one.

After Russian America was sold to the U.S., all the holdings of the Russian–American Company were liquidated.

The Department of Alaska (1867-1884)

The United States flag was raised on 18 October 1867 (now called Alaska Day). Coincident with the ownership change, the de facto International Date Line was moved westward, and Alaska changed from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar. Therefore, for residents, Friday, October 6, 1867 was followed by Friday, October 18, 1867—two Fridays in a row because of the date line shift.

During the Department era, from 1867 to 1884, Alaska was variously under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army (until 1877), the United States Department of the Treasury (from 1877 until 1879) and the U.S. Navy (from 1879 until 1884).

When Alaska was first purchased, most of its land remained unexplored. In 1865, Western Union laid a telegraph line across Alaska to the Bering Strait where it would connect, under water, with an Asian line. It also conducted the first scientific studies of the region and produced the first map of the entire Yukon River. The Alaska Commercial Company and the military also contributed to the growing exploration of Alaska in the last decades of the 1800s, building trading posts along the Interior's many rivers.

District of Alaska (1884-1912)

In 1884, the region was organized and the name was changed from the Department of Alaska to the District of Alaska. At the time, legislators in Washington, D.C., were occupied with post-Civil War reconstruction issues, and had little time to dedicate to Alaska. In 1896, the discovery of gold in Yukon Territory in neighboring Canada, brought many thousands of miners and new settlers to Alaska, and very quickly ended the nation's four year economic depression. Although it was uncertain whether gold would also be found in Alaska, Alaska greatly profited because it was along the easiest transportation route to the Yukon goldfields. Numerous new cities, such as Skagway, Alaska, owe their existence to a gold rush in Canada. No history of Alaska would be complete without mention of Soapy Smith, the crime boss confidence man who operated the largest criminal empire in gold rush era Alaska, until he was shot down by vigilantes. Today, he is known as "Alaska's Outlaw."

In 1899, gold was found in Alaska itself in Nome, and several towns subsequently began to be built, such as Fairbanks and Ruby. In 1902, the Alaska Railroad began to be built, which would connect from Seward to Fairbanks by 1914, though Alaska still does not have a railroad connecting it to the lower 48 states today. Still, an overland route was built, cutting transportation times to the contiguous states by days. The industries of copper mining, fishing, and canning began to become popular in the early 1900s, with 10 canneries in some major towns.

In 1903, a boundary dispute with Canada was finally resolved.

By the turn of the 20th century, commercial fishing was gaining a foothold in the Aleutian Islands. Packing houses salted cod and herring, and salmon canneries were opened. Another traditional occupation, whaling, continued with no regard for over-hunting. They pushed the bowhead whales to the edge of extinction for the oil in their tissue. The Aleuts soon suffered severe problems due to the depletion of the fur seals and sea otters which they needed for survival. As well as requiring the flesh for food, they also used the skins to cover their boats, without which they could not hunt. The Americans also expanded into the Interior and Arctic Alaska, exploiting the furbearers, fish, and other game on which Natives depended.

20th century

Alaska Territory (1912-1959)

When Congress passed the Second Organic Act in 1912, Alaska was reorganized, and renamed the Territory of Alaska. By 1916, its population was about 58,000. James Wickersham, a Delegate to Congress, introduced Alaska's first statehood bill, but it failed due to the small population and lack of interest from Alaskans. Even President Warren G. Harding's visit in 1923 could not create widespread interest in statehood. Under the conditions of the Second Organic Act, Alaska had been split into four divisions. The most populous of the divisions, whose capital was Juneau, wondered if it could become a separate state from the other three. Government control was a primary concern, with the territory having 52 federal agencies governing it.

Then, in 1920, the Jones Act required U.S.-flagged vessels to be built in the United States, owned by U.S. citizens, and documented under the laws of the United States. All goods entering or leaving Alaska had to be transported by American carriers and shipped to Seattle prior to further shipment, making Alaska dependent on Washington. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the provision of the Constitution saying one state should not hold sway over another's commerce did not apply because Alaska was only a territory. The prices Seattle shipping businesses charged began to rise to take advantage of the situation. This situation created an atmosphere of enmity among Alaskans who watched the wealth being generated by their labors flowing into the hands of Seattle business holdings.

The Depression caused prices of fish and copper, which were vital to Alaska's economy at the time, to decline. Wages were dropped and the workforce decreased by more than half. In 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt thought Americans from agricultural areas could be transferred to Alaska's Matanuska-Susitna Valley for a fresh chance at agricultural self-sustainment. Colonists were largely from northern states, such as Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota under the belief that only those who grew up with climates similar to that of Alaska's could handle settler life there. The United Congo Improvement Association asked the president to settle 400 African-American farmers in Alaska, saying that the territory would offer full political rights, but racial prejudice and the belief that only those from northern states would make suitable colonists caused the proposal to fail.

The exploration and settlement of Alaska would not have been possible without the development of the aircraft, which allowed for the influx of settlers into the state's interior, and rapid transportation of people and supplies throughout. However, due to the unfavorable weather conditions of the state, and high ratio of pilots-to-population, over 1700 aircraft wreck sites are scattered throughout its domain. Numerous wrecks also trace their origins to the military build-up of the state during both World War II and the Cold War.

- See also History of aviation in Alaska

World War II

During World War II, three of the outer Aleutian Islands—Attu, Agattu and Kiska—were invaded and occupied by Japanese troops. They were the only part of the continental territory of the United States to be occupied by the enemy during the war. Their recovery became a matter of national pride.

On June 3, 1942, the Japanese launched an air attack on Dutch Harbour, a U.S. naval base on Unalaska Island, but were repelled by U.S. forces. A few days later, the Japanese landed on the islands of Kiska and Attu, where they overwhelmed Attu villagers. The villagers were taken to Japan, where they were interned for the remainder of the war. Aleuts from the Pribilofs and Aleutian villages were evacuated by the United States to Southeast Alaska.

Attu was regained in May 1943 after two weeks of intense fighting and 3,929 American casualties. The U.S. then turned its attention to the other occupied island, Kiska. From June through August, tons of bombs were dropped on the tiny island, though the Japanese ultimately escaped via transport ships. After the war, the Native Attuans who had survived their internment were resettled to Atka by the federal government, which considered their home villages too remote to defend.

In 1942, during World War II the Alaska–Canada Military Highway was completed, in part to form an overland supply route to America's Russian allies on the other side of the Bering Strait. Running from Great Falls, Montana, to Fairbanks, the road was the first stable link between Alaska and the rest of America. The construction of military bases, such as the Adak base, contributed to the population growth of some Alaskan cities. Anchorage almost doubled in size, from 4,200 people in 1940 to 8,000 in 1945.

Statehood

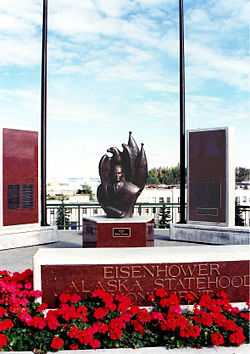

By the turn of the 20th century, a movement pushing for Alaska statehood began, but in the contiguous 48 states, legislators were worried that Alaska's population was too sparse, distant, and isolated, and its economy was too unstable for it to be a worthwhile addition to the United States. World War II and the Japanese invasion highlighted Alaska's strategic importance, and the issue of statehood was taken more seriously, but it was the discovery of oil at Swanson River on the Kenai Peninsula that dispelled the image of Alaska as a weak, dependent region. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Alaska Statehood Act into United States law on 7 July 1958, which paved the way for Alaska's admission into the Union on January 3, 1959. Juneau, the territorial capital, continued as state capital, and William A. Egan was sworn in as the first governor.

Alaska has no counties, as do other states in the United States. Instead, it is divided into 16 boroughs and one " unorganized borough" made up of all land not within any borough. Boroughs have organized area-wide governments, but within the unorganized borough, where there is no such government, services are provided by the state. The unorganized borough is divided into artificially-created census areas by the United States Census Bureau for statistical purposes only.

The "Good Friday Earthquake"

On March 27, 1964 the " Good Friday Earthquake" struck South-central Alaska, churning the earth for four minutes with a magnitude of 9.2. The earthquake was one of the most powerful ever recorded and killed 131 people. Most of them were drowned by the tsunamis that tore apart the towns of Valdez and Chenega. Throughout the Prince William Sound region, towns and ports were destroyed and land was uplifted or shoved downward. The uplift destroyed salmon streams, as the fish could no longer jump the various newly created barriers to reach their spawning grounds. Ports at Valdez and Cordova were beyond repair, and the fires destroyed what the mudslides had not. At Valdez, an Alaska Steamship Company ship was lifted by a huge wave over the docks and out to sea, but most hands survived. At Turnagain Arm, off Cook Inlet, the incoming water destroyed trees and caused cabins to sink into the mud. On Kodiak, a tidal wave wiped out the villages of Afognak, Old Harbour, and Kaguyak and damaged other communities, while Seward lost its harbour. Despite the extent of the catastrophe, Alaskans rebuilt many of the communities.

1968 to present: oil and land politics

Oil discovery, ANSCA, and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline

The 1968 discovery of oil on the North Slope's Prudhoe Bay--which would turn out to have the most recoverable oil of any field in the United States-- would change Alaska's political landscape for decades.

This discovery catapulted the issue of Native land ownership into the headlines. In the mid-1960s, Alaska Natives from many tribal groups had united in an effort to gain title to lands wrested from them by Europeans, but the government had responded slowly before the Prudhoe Bay discovery. The government finally took action when permitting for a pipeline crossing the state, necessary to get Alaskan oil to market, was stalled pending the settlement of Native land claims.

In 1971, with major petroleum dollars on the line, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was signed into law by Richard Nixon. Under the Act, Natives relinquished aboriginal claims to their lands in exchange for access to 44 million acres (180,000 km²) of land and payment of $963 million. The settlement was divided among regional, urban, and village corporations, which managed their funds with varying degrees of success.

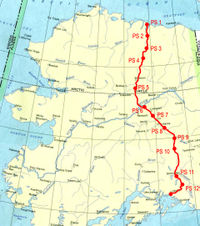

Though a pipeline from the North Slope to the nearest ice-free port, almost 800 miles (1,300 km) to the south, was the only way to get Alaska's oil to market, significant engineering challenges lay ahead. Between the North Slope and Valdez, there were active fault lines, three mountain ranges, miles of unstable, boggy ground underlain with frost, and migration paths of caribou and moose. The Trans-Alaska Pipeline was ultimately completed in 1977 at a total cost of $8 billion.

The pipeline allowed an oil bonanza to take shape. Per capita incomes rose throughout the state, with virtually every community benefiting. State leaders were determined that this boom would not end like the fur and gold booms, in an economic bust as soon as the resource had disappeared. In 1976, the state's constitution was amended to establish the Alaska Permanent Fund, in which a quarter of all mineral lease proceeds is invested. Income from the fund is used to pay annual dividends to all residents who qualify, to increase the fund's principal as a hedge against inflation, and to provide funds for the state legislature. Since 1993, the fund has produced more money than the Prudhoe Bay oil fields, whose production is diminishing. In March 2005, the fund's value was over $30 billion.

Environmentalism, the Exxon-Valdez, and ANWR

Oil production was not the only economic value of Alaska's land, however. In the second half of the 20th century, Alaska discovered tourism as an important source of revenue. Tourism became popular after World War II, when men stationed in the region returned home praising its natural splendor. The Alcan Highway, built during the war, and the Alaska Marine Highway System, completed in 1963, made the state more accessible than before. Tourism became increasingly important in Alaska, and today over 1.4 million people visit the state each year.

With tourism more vital to the economy, environmentalism also rose in importance. The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) of 1980 added 53.7 million acres (217,000 km²) to the National Wildlife Refuge system, parts of 25 rivers to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system, 3.3 million acres (13,000 km²) to National Forest lands, and 43.6 million acres (176,000 km²) to National Park land. Because of the Act, Alaska now contains two-thirds of all American national parklands. Today, more than half of Alaskan land is owned by the Federal Government.

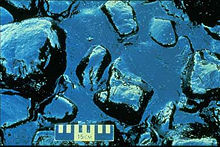

The possible environmental repercussions of oil production became clear in the Exxon Valdez oil spill of 1989. On March 24, the tanker Exxon Valdez ran aground in Prince William Sound, releasing 11 million gallons of crude oil into the water, spreading along 1,100 miles (1,800 km) of shoreline. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, at least 300,000 sea birds, 2,000 otters, and other marine animals died because of the spill. Exxon spent US$2 billion on cleaning up in the first year alone. Exxon, working with state and federal agencies, continued its cleanup into the early 1990s. Government studies show that the oil and the cleaning process itself did long-term harm to the ecology of the Sound, interfering with the reproduction of birds and animals in ways that still aren't fully understood. Prince William Sound seems to have recuperated, but scientists still dispute the extent of the recovery. In a civil settlement, Exxon agreed to pay $900 million in ten annual payments, plus an additional $100 million for newly discovered damages. In a class action suit against Exxon, a jury awarded punitive damages of US$5 billion, but as of 2007 no money has been disbursed and appellate litigation continues.

Today, the tension between preservation and development is seen in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) drilling controversy. The question of whether to allow drilling for oil in ANWR has been a political football for every sitting American president since Jimmy Carter. Studies performed by the US Geological Survey have shown that the " 1002 area" of ANWR, located just east of Prudhoe Bay, contains large deposits of crude oil. Traditionally, Alaskan residents, trade unions, and business interests have supported drilling in the refuge, while environmental groups and many within the Democratic Party have traditionally opposed it. Among native Alaskan tribes, support is mixed. In the 1990s and 2000s, votes about the status of the refuge occurred repeatedly in the U.S. House and Senate, but as of 2007 efforts to allow drilling have always been ultimately thwarted by filibusters, amendments, or vetoes.

Notable historical figures

- Clarence L. Andrews customs official and an information officer, recognized authority on the history and culture of the Alaskan territory in early 1900's, photographer, author

- Alexandr Baranov (1746-1819) trader, public official, Russia

- Edward Lewis "Bob" Bartlett (1904–1968) was the territorial delegate to the US Congress from 1944 to 1958, and was elected as the first senior U.S. Senator in 1958 and re-elected to a full 6-year term in 1960 and again in 1966. There are streets, buildings, a high school and even the first state ferry, named for him.

- Benny Benson, designed state flag at age 13, Chignik

- Vitus Bering (1681-1741) explorer

- Charles E. Bunnell educator

- Jimmy Doolittle (1896-1993) (James Harold "Jimmy" Doolittle) served with great distinction as a general in the United States Army Air Forces during the Second World War, earning the Medal of Honour as the commander of the Doolittle Raid.

- Wyatt Earp (1848-1929) lived in Alaska from 1897 to 1901; he built the Dexter Saloon in Nome, Alaska with C.E. Hoxsie.

- William A. Egan (1914-1984) served two years as an "Alaska-Tennessee Plan" Senator in Washington D.C. prior to becoming the first Governor of Alaska, and remains the only Alaskan Governor to serve three terms.

- Carl Ben Eielson pioneer pilot

- Vic Fischer emeritus professor and one of two remaining signers of the Alaska Constitution

- Henry Ernest Gruening (1886–1974) was appointed Governor of the Territory of Alaska in 1939, and served in that position for fourteen years. He was elected to the United States Senate in 1958 and re-elected in 1962 and served until 1969. One of two Senators who voted against Tonkin Gulf Resolution at beginning of the heaviest period of the Vietnam War.

- Jay Hammond (1922–2005) was Governor during the building of the Alaska Pipeline and established the Alaska Permanent Fund, providing Alaskans with essentially free money. He is regarded as somewhat of a hero because of this. He was also governor during passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act and effectively served to moderate associated issues within the state among disparate interest groups ranging from conservationists to natives to pro-development interests.

- B. Frank Heintzleman territorial governor

- Saint Herman of Alaska (1756-1837) Russian missionary, first Eastern Orthodox saint in North America.

- Walter Hickel former governor

- Sheldon Jackson (1834-1909) an American missionary and educator, the first federal superintendent of public instruction for Alaska, and bearer of the first reindeer to Alaska from Siberia. The Sheldon Jackson Museum and College are located in Sitka.

- Joseph Juneau (1836–1899) and Richard Harris (1833-1907), prospectors and founders of what is now Alaska's capital city, Juneau.

- Austin Eugene "Cap" Lathrop industrialist

- Ray Mala (1906-1952) is the first Native American movie star and the only film star the state of Alaska has yet to produce. He starred in MGM's Oscar-winning classic Eskimo/Mala the Magnificent filmed entirely on location in Alaska. His son Dr. Ted Mala became the first Alaska native male to become a Doctor. Dr. Mala served on Governor Walter J. Hickel's cabinet (1990) as Commissioner of Health and Social Services.

- Eva McGown (1883-1972), Fairbanks hostess and chorister

- John Muir (1838-1914), naturalist, explorer, and conservationist who detailed his amazing journeys in Alaska Territory and was instrumental, through his friendship with President Theodore Roosevelt, in protecting substantial area of forest wilderness and wildlife preserves in Alaska.

- William Oefelein (b. 1965) Alaska's first astronaut. His first mission, STS-116. Commander Oefelein received his commission as an Ensign in the United States Navy from Aviation Officer Candidate School in Pensacola, Florida in 1988.

- Sarah Palin (b. 1964) Alaska's youngest Governor and first female Governor

- Elizabeth Peratrovich (1911-1958) a Native ( Tlingit) Alaskan who fought for equality of Native Alaskans and is honored with "Elizabeth Peratrovich Day."

- George Sharrock (1910–2005) moved to the territory before statehood, eventually elected as the mayor of Anchorage and served during the Good Friday Earthquake in March 1964. This was the most devastating earthquake to hit Alaska and it sunk beach property, damaged roads and destroyed buildings all over the south central area. Sharrock, sometimes called the "earthquake mayor," led the city's rebuilding effort over six months.

- Soapy Smith, Jefferson Randolph Smith, "Alaska's Outlaw." The infamous confidence man and early settler, who ran the goldrush town of Skagway, Alaska, 1897-98.

- Fran Ulmer was the first woman elected to statewide office—she became Lieutenant Governor in 1994.

- Saint Innocent of Alaska (1797-1879) First Russian Orthodox bishop in North America

- Joe Vogler (1913-1993) founder of the Alaskan Independence Party

- Noel Wien (1899-1977) aviation pioneer, founder of Wien Air Alaska, first to make a round trip between Alaska and Asia.

- Ferdinand von Wrangell (1797-1870) explorer, president of the Russian-American Company in 1840-1849.