Vietnam War

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Military History and War

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Vietnam War, also known as the Second Indochina War, the Vietnam Conflict, and, in Vietnam, the American War, occurred from March 1959 to April 30, 1975. The war was fought between the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) and its communist allies and the US-supported Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam).

Throughout the conflict the less equipped and trained Vietcong fought a guerilla war and North Vietnamese soldiers fought a conventional war against US forces in the region, using the jungles of Vietnam to spring deadly ambushes whilst the United States used overwhelming firepower in artillery and aircraft to grind down offensives and potential Vietcong bases. In particular, the iconic Huey helicopters played a decisive role in air-lifting supplies and when later upgraded with rockets and machine guns took part in the heavy ground conflicts.

In 1965 the United States sent in troops to prevent the South Vietnamese government from collapsing. Ultimately, however, the United States failed to achieve its goal, and in 1975 Vietnam was reunified under Communist control; in 1976 it officially became the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. During the conflict, approximately 3 to 4 million Vietnamese on both sides were killed, in addition to another 1.5 to 2 million Lao and Cambodians who were drawn into the war.

Terminology

Various names have been applied to the conflict, and these have shifted over time, although Vietnam War is the most commonly used title in English. It has been variously called the Second Indochina War, the Vietnam Conflict, the Vietnam War. In Vietnamese, the war is commonly known as Chiến tranh Việt Nam (The Vietnam War), or more officially as Kháng chiến chống Mỹ (Resistance War against America).

The main military organizations involved in the war were, on the side of the South, the U.S. military and the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), and, on the side of the North, the Vietnam People's Army (VPA), also known as the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) or the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), and the communist guerrilla forces in the South named the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF), also known as the Viet Cong.

Background to 1949

History of Vietnam

Exit of the French, 1950–1954

In 1950, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the People's Republic of China (PRC) recognized each other diplomatically. The Soviet Union quickly followed suit. U.S. President Harry S. Truman countered by recognizing the French puppet government of Vietnam. Washington, seemingly ignorant of the long historical antipathy between Vietnam and China, feared that Hanoi was a pawn of the PRC and, by extension, Moscow. As historian and former Hanoi foreign minister Luu Doan Huynh has commented, “Vietnam a part of the Chinese expansionist game in Asia? For anyone who knows the history of Indochina, this is incomprehensible.” Nevertheless, Chinese support was very important to the Viet Minh's success, and China largely supported the Vietnamese Communists through the end of the war.

The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 marked a decisive turning point. From the perspective of many in Washington, what had been a colonial war in Indochina was transformed into another example of communist expansionism directed by the Kremlin.

In 1950, the U.S. Military Assistance and Advisory Group (MAAG) arrived to screen French requests for aid, advise on strategy, and train Vietnamese soldiers. By 1954, the U.S. had supplied 300,000 small arms and spent one billion dollars in support of the French military effort. The Eisenhower administration was shouldering 80 percent of the cost of the war. The Viet Minh received crucial support from the Soviet Union and the PRC. Chinese support in the Border Campaign of 1950 allowed supplies to come from China into Vietnam. Throughout the conflict, U.S. intelligence estimates remained skeptical of French chances of success.

The Battle of Dien Bien Phu marked the end of French involvement in Indochina. The Viet Minh and their mercurial commander Vo Nguyen Giap handed the French a stunning military defeat. On May 7, 1954, the French Union garrison surrendered. At the Geneva Conference the French negotiated a ceasefire agreement with the Viet Minh. Independence was granted to Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. As a U.S. Army study noted, France lost the war primarily because it “neglected to cultivate the loyalty and support of the Vietnamese people.” More than 400,000 civilians and soldiers had died during the nine year conflict.

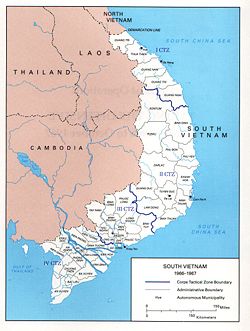

Vietnam was temporarily partitioned at the 17th parallel, and under the terms of the Geneva Convention, civilians were to be given the opportunity to freely move between the two provisional states. Elections throughout the country were to be held, according to the Geneva accords, but never took place. Nearly one million northerners (mainly Catholics) fled south in “understandable terror” of Ho Chi Minh's new regime. It is estimated that as many as two million more would have left had they not been stopped by the Viet Minh. In the north, the Viet Minh established a socialist state—the Democratic Republic of Vietnam—and engaged in a land reform program in which the mass killing of perceived “class enemies” occurred. Ho Chi Minh later apologized. In the south a non-communist state was established under the Emperor Bao Dai, a former puppet of the French and the Japanese. Ngo Dinh Diem became his Prime Minister. In addition to the Catholics flowing south, up to 90,000 Viet Minh fighters went north for “regroupment” as envisioned by the Geneva Accords. However, in contravention of the Accords, the Viet Minh left roughly 5,000 to 10,000 cadres in South Vietnam as a “politico-military substructure within the object of its irredentism.”

President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles greet President Ngo Dinh Diem in Washington.

|

Diem era, 1955–1963

As dictated by the Geneva Conference of 1954, the partition of Vietnam was meant to be only temporary, pending national elections on July 20, 1956. Much as in Korea, the agreement stipulated that the two military zones were to be separated by a temporary demarcation line (known as the Demilitarized Zone or DMZ). The United States, alone among the great powers, refused to sign the Geneva agreement. The president of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, declined to hold elections. This called into question the United States' commitment to democracy in the region, but also raised questions about the legitimacy of any election held in the communist-run North. President Dwight D. Eisenhower expressed U.S. fears when he wrote that, in 1954, “80 per cent of the population would have voted for the Communist Ho Chi Minh” over Emperor Bao Dai. However, this wide popularity was expressed before Ho's disastrous land reform program and a peasant revolt in Ho's home province which was bloodily suppressed.

The cornerstone of U.S. policy was the Domino Theory. This argued that if South Vietnam fell to communist forces, then all of South East Asia would follow. Popularized by the Eisenhower Administration, some argued that if communism spread unchecked, it would follow them home by first reaching Hawaii and follow to the West Coast of the United States. It was better, therefore, to fight communism in Asia, rather than on American soil.

Rule

Ngo Dinh Diem was chosen by the U.S. to lead South Vietnam. A devout Roman Catholic, he was fervently anti-communist and was “untainted” by any connection to the French. He was one of the few prominent Vietnamese nationalists who could claim both attributes. Historian Luu Doan Huynh notes, however, that “Diem represented narrow and extremist nationalism coupled with autocracy and nepotism.”

The new American patrons were almost completely ignorant of Vietnamese culture. They knew little of the language or long history of the country. There was a tendency to assign American motives to Vietnamese actions, and Diem warned that it was an illusion to believe that blindly copying Western methods would solve Vietnamese problems.

In April and June 1955, Diem (against U.S. advice) cleared the decks of any political opposition by launching military operations against the Cao Dai religious sect, the Buddhist Hoa Hao, and the Binh Xuyen organized crime group (which was allied with members of the secret police and some military elements). Diem accused these groups of harboring Communist agents. As broad-based opposition to his harsh tactics mounted, Diem increasingly sought to blame the communists.

Beginning in the summer of 1955, he launched the “Denounce the Communists” campaign, during which communists and other anti-government elements were arrested, imprisoned, tortured, or executed. Opponents were labeled Viet Cong by the regime to degrade their nationalist credentials. During this period refugees moved across the demarcation line in both directions. Around 52,000 Vietnamese civilians moved from south to north. However a staggering 450,000 people fled north Vietnam to the south, in aircraft and ships provided by France and the U.S. CIA propaganda efforts increased the outflow with slogans such as “the Virgin Mary is going South.” The northern refugees were meant to give Diem a strong anti-communist constituency.

In a referendum on the future of the monarchy, Diem rigged the poll supervised by his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu and received “98.2 percent” of the vote. His American advisers had recommended a more modest winning margin of “60 to 70 percent.” Diem, however, viewed the election as a test of authority. On October 26, 1955, Diem declared the new Republic of Vietnam, with himself as president. The Republic of Vietnam was created largely because of the Eisenhower administration's desire for an anti-communist state in the region. Colonel Edward Lansdale, a CIA officer, became an important advisor to the new president.

As a wealthy Catholic, Diem was viewed by many ordinary Vietnamese as part of the old elite who had helped the French rule Vietnam. The majority of Vietnamese people were Buddhist, so his attack on the Buddhist community served only to deepen mistrust. Diem's human rights abuses increasingly alienated the population.

In May, Diem undertook a ten-day state visit to the United States. President Eisenhower pledged his continued support. A parade in New York City was held in his honour. Although Diem was openly praised, in private Secretary of State John Foster Dulles conceded that he had been selected because there were no better alternatives.

Insurgency in the South, 1956–1960

In 1956 one of the leading communists in the south, Le Duan, returned to Hanoi to urge the Vietnam Workers' Party to take a firmer stand on the reunification of Vietnam under Communist leadership. But Hanoi (then in a severe economic crisis) hesitated to launch a full-scale military struggle. The northern Communists feared U.S. intervention and believed that conditions in South Vietnam were not yet ripe for a "people's revolution." However, in December 1956, Ho Chi Minh authorized the Viet Minh cadres still in South Vietnam to begin a low level insurgency. In North Vietnamese political theory, the action was a subset of "political struggle" called "armed propaganda," and consisted mostly of kidnappings and terrorist attacks.

Four hundred government officials were assassinated in 1957 alone, and the violence gradually increased. While the terror was originally aimed at local government officials, it soon broadened to include other symbols of the status quo, such as schoolteachers, health workers, and agricultural officials. One estimate says that by 1958, 20 percent of South Vietnam's village chiefs had been murdered by the insurgents. The insurgency sought to completely destroy government control in South Vietnam's rural villages and replace it with a shadow government. Finally, in January 1959, under pressure from southern cadres who were being targeted by Diem's secret police, the North's Central Committee issued a secret resolution authorizing an "armed struggle." This authorized the southern Viet Minh to begin large-scale operations against the South Vietnamese military. In response, Diem enacted tough new anti-communist laws. However, North Vietnam supplied troops and supplies in earnest, and the infiltration of men and weapons from the north began along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Observing the increasing unpopularity of the Diem regime, on December 12, 1960, Hanoi authorized the creation of the National Liberation Front as a front group for the Vietcong, the communist army in the South.

Successive American administrations, as Robert McNamara and others have noted, overestimated the control that Hanoi had over the NLF. Diem's paranoia, repression, and incompetence progressively angered large segments of the population of South Vietnam. Thus, many maintain that the origins of the anti-government violence were homegrown, rather than inspired by Hanoi. However, as historian Douglas Pike has pointed out, “today, no serious historian would defend the thesis that North Vietnam was not involved in the Vietnam war from the start…. To maintain this thesis today, one would be obliged to deal with the assertions of Northern involvement that have poured out of Hanoi since the end of the war."

John F. Kennedy's Escalation of the War, 1960–1963

When John F. Kennedy won the 1960 U.S. presidential election, one major issue Kennedy raised was whether the Soviet space and missile programs had surpassed those of the U.S. As Kennedy took over, despite warnings from Eisenhower about Laos and Vietnam, Europe and Latin America "loomed larger than Asia on his sights." In his inaugural address, Kennedy made the ambitious pledge to "pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and success of liberty."

In June 1961, John F. Kennedy bitterly disagreed with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev when they met in Vienna over key U.S.-Soviet issues. Cold war strategists concluded Southeast Asia would be one of the testing grounds where Soviet forces would test the USA's containment policy—begun during the Truman Administration and solidified by the stalemate resulting from the Korean War.

Although Kennedy stressed long-range missile parity with the Soviets, he was also interested in using special forces for counterinsurgency warfare in Third World countries threatened by communist insurgencies. Although they were originally intended for use behind front lines after a conventional invasion of Europe, Kennedy believed that the guerrilla tactics employed by special forces such as the Green Berets would be effective in a "brush fire" war in Vietnam. He saw British success in using such forces in Malaya as a strategic template.

The Kennedy administration remained essentially committed to the Cold War foreign policy inherited from the Truman and Eisenhower administrations. In 1961, Kennedy faced a three-part crisis—the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion, the construction of the Berlin Wall, and a negotiated settlement between the pro-Western government of Laos and the Pathet Lao communist movement These made Kennedy believe that another failure on the part of the United States to gain control and stop communist expansion would fatally damage U.S. credibility with its allies and his own reputation. Kennedy determined to "draw a line in the sand" and prevent a communist victory in Vietnam, saying, "Now we have a problem making our power credible and Vietnam looks like the place," to James Reston of the New York Times immediately after meeting Khrushchev in Vienna. Kennedy increased the number of U.S. military in Vietnam from 800 to 16,300.

In May 1961, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson visited Saigon and enthusiastically declared Diem the "Winston Churchill of Asia." Asked why he had made the comment, Johnson replied, "Diem's the only boy we got out there." Johnson assured Diem of more aid in molding a fighting force that could resist the communists.

Kennedy's policy toward South Vietnam rested on the assumption that Diem and his forces must ultimately defeat the guerrillas on their own. He was against the deployment of American combat troops and observed that "to introduce U.S. forces in large numbers there today, while it might have an initially favorable military impact, would almost certainly lead to adverse political and, in the long run, adverse military consequences."

The quality of the South Vietnamese military, however, remained poor. Bad leadership, corruption, and political interference all played a part in emasculating the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). The frequency of guerrilla attacks rose as the insurgency gathered steam. Hanoi's support for the NLF played a significant role. But South Vietnamese governmental incompetence was at the core of the crisis. Kennedy advisers Maxwell Taylor and Walt Rostow recommended that U.S. troops be sent to South Vietnam disguised as flood relief workers. Kennedy rejected the idea but increased military assistance yet again. In April 1962, John Kenneth Galbraith warned Kennedy of the "danger we shall replace the French as a colonial force in the area and bleed as the French did." By mid-1962, the number of U.S. military advisers in South Vietnam had risen from 700 to 12,000.

The Strategic Hamlet Program had been initiated in 1961. This joint U.S.-South Vietnamese program attempted to resettle the rural population into fortified camps. The aim was to isolate the population from the insurgents, provide education and health care, and strengthen the government's hold over the countryside. The Strategic Hamlets, however, were quickly infiltrated by the guerrillas. The peasants resented being uprooted from their ancestral villages. The government refused to undertake land reform, which left farmers paying high rents to a few wealthy landlords. Corruption dogged the program and intensified opposition. Government officials were targeted for assassination. The Strategic Hamlet Program collapsed two years later.

On July 23, 1962, fourteen nations, including the People's Republic of China, South Vietnam, the Soviet Union, North Vietnam and the United States, signed an agreement promising the neutrality of Laos.

Coup and assassinations

Some policy-makers in Washington began to conclude that Diem was incapable of defeating the communists and might even make a deal with Ho Chi Minh. He seemed concerned only with fending off coups. As Robert F. Kennedy noted, "Diem wouldn't make even the slightest concessions. He was difficult to reason with …" During the summer of 1963 U.S. officials began discussing the possibility of a regime change. The United States Department of State was generally in favour of encouraging a coup. The Pentagon and CIA were more alert to the destabilizing consequences of such an act and wanted to continue applying pressure for reforms.

Chief among the proposed changes was the removal of Diem's younger brother Ngo Dinh Nhu. Nhu controlled the secret police and was seen as the man behind the Buddhist repression. As Diem's most powerful adviser, Nhu had become a hated figure in South Vietnam. His continued influence was unacceptable to the Kennedy administration. Eventually, the administration concluded that Diem was unwilling to change.

The CIA was in contact with generals planning to remove Diem. They were told that the United States would support such a move. President Diem was overthrown and executed, along with his brother, on November 2, 1963. When he was informed, Maxwell Taylor remembered that Kennedy "rushed from the room with a look of shock and dismay on his face." He had not approved Diem's murder. The U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge, invited the coup leaders to the embassy and congratulated them. Ambassador Lodge informed Kennedy that "the prospects now are for a shorter war".

Following the coup, chaos ensued. Hanoi took advantage of the situation and increased its support for the guerrillas. South Vietnam entered a period of extreme political instability, as one military government toppled another in quick succession. Increasingly, each new regime was viewed as a puppet of the Americans; whatever the failings of Diem, his credentials as a nationalist (as Robert McNamara later reflected) had been impeccable.

Kennedy increased the number of U.S. military advisers from 800 to 16,300 to cope with rising guerrilla activity. The advisers were embedded at every level of the South Vietnamese armed forces. They were, however, almost completely ignorant of the political nature of the insurgency. The insurgency was a political power struggle, in which military engagements were not the main goal. The Kennedy administration sought to refocus U.S. efforts on pacification and "winning over the hearts and minds" of the population. The military leadership in Washington, however, was hostile to any role for U.S. advisers other than conventional troop training. General Paul Harkins, the commander of U.S. forces in South Vietnam, confidently predicted victory by Christmas 1963. The CIA was less optimistic, however, warning that "the Viet Cong by and large retain de facto control of much of the countryside and have steadily increased the overall intensity of the effort".

In a conversation with Nobel Peace Prize winner and Canadian prime minister Lester B. Pearson, Kennedy sought his advice. "Get out," Pearson replied. "That's a stupid answer," shot back Kennedy. "Everyone knows that. The question is: How do we get out?" Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, just three weeks after Diem.

Kennedy had introduced helicopters to the war and created a joint U.S.-South Vietnamese Air Force, staffed with American pilots. He also sent in the Green Berets. He was succeeded by his vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, who reaffirmed America's support of South Vietnam. By the end of the year Saigon had received $500 million in military aid.

United States goes to war, 1963–1969

Lyndon Johnson, as he took over the presidency after the death of Kennedy, did not consider Vietnam a priority and was more concerned with his " Great Society" and progressive social programs. Johnson had a difficult time with American foreign policy makers, specifically Averill Harriman and Dean Acheson, who to Johnson's mind spoke a different language. Particularly heated was the relationship between the new president and national security advisor McGeorge Bundy. Shortly after the assassination of Kennedy, when Bundy called LBJ on the phone, LBJ responded:

"Goddammit, Bundy. I've told you that when I want you I'll call you."

On November 24, 1963, Johnson brought a small group together to talk with Henry Cabot Lodge, and the new president provided his support to help win the Vietnam war. But the pledge came at a time when Vietnam was deteriorating, especially in places like the Mekong Delta, because of the recent coup against Diem.

The military revolutionary council, meeting in lieu of a strong South Vietnamese leader, was made up of 12 members headed by General Minh—whom Stanley Karnow, a journalist on the ground, later recalled as "a model of lethargy." His regime was overthrown in January 1964 by General Nguyen Khanh. Lodge, frustrated by the end of year, cabled home about Minh: "Will he be strong enough to get on top of things?"

On August 2, 1964, the USS Maddox, on an intelligence mission along North Vietnam's coast, fired upon and damaged several torpedo boats that had been stalking it in the Gulf of Tonkin. A second attack was reported two days later on the USS Turner Joy and Maddox in the same area. The circumstances of the attack were murky. Lyndon Johnson commented to Undersecretary of State George Ball that "those sailors out there may have been shooting at flying fish." The second attack led to retaliatory air strikes, prompted Congress to approve the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, and gave the president power to conduct military operations in Southeast Asia without declaring war. In the same month, Johnson pledged that he was not "...committing American boys to fighting a war that I think ought to be fought by the boys of Asia to help protect their own land."

In 2005, however, an NSA declassified report revealed that there was no attack on 4 August. It had already been called into question long before this. "The Gulf of Tonkin incident," writes Louise Gerdes, "is an oft-cited example of the way in which Johnson misled the American people to gain support for his foreign policy in Vietnam." George C. Herring argues, however, that McNamara and the Pentagon "did not knowingly lie about the alleged attacks, but they were obviously in a mood to retaliate and they seem to have selected from the evidence available to them those parts that confirmed what they wanted to believe." Rising from 5,000 in 1959, there were now 100,000 guerrilla fighters in 1964. Some have argued that ten soldiers are needed to deal with every one insurgent. Thus, the total number of U.S. troops in 1964 needed to defeat the insurgents may have exceeded the entire strength of the United States Army.

The National Security Council recommended a three-stage escalation of the bombing of North Vietnam. On March 2, 1965, following an attack on a U.S. Marine barracks at Pleiku, Operation Flaming Dart and Operation Rolling Thunder commenced. The bombing campaign, which ultimately lasted three years, was intended to force North Vietnam to cease its support for the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF) by threatening to destroy North Vietnam's air defenses and industrial infrastructure. As well, it was aimed at bolstering the morale of the South Vietnamese. Between March 1965 and November 1968, "Rolling Thunder" deluged the north with a million tons of missiles, rockets and bombs. Bombing was not restricted to North Vietnam. Other aerial campaigns, such as Operation Commando Hunt, targeted different parts of the NLF and Vietnam People's Army (VPA) infrastructure. These included the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which ran through Laos and Cambodia. The objective of forcing North Vietnam to stop its support for the NLF, however, was never reached. As one officer noted "this is a political war and it calls for discriminate killing. The best weapon … would be a knife … The worst is an airplane." The Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force Curtis LeMay, however, had long advocated saturation bombing in Vietnam and wrote of the Communists that "we're going to bomb them back into the Stone Age".

Escalation and ground war

Escalation of the Vietnam War officially started on the morning of January 31, 1965, when orders were cut and issued to mobilize the 18th TAC Fighter Squadron from Okinawa to Danang air force base (AFB). A red alert alarm to scramble was sounded at Kadena AFB at 3:00 a.m. F-105s, pilots, and support were deployed from Okinawa and landed in Vietnam that afternoon to join up with other smaller units who had already arrived weeks earlier. Preparations were under way for the first step of Operation Flaming Dart. The mission of Operation Flaming Dart, to cross the Seventeenth Parallel into North Vietnam, had already been planned and was in place before the NLF attack on Pleiku airbase on February 6. On February 7, forty-nine F-105 Thunderchiefs flew out of Danang AFB to targets located in North Vietnam. From this day forward the war was no longer confined to South Vietnam. It took almost an hour to get all forty nine of the F-105's in the air. On that morning, the continuous loud roar of the F-105 engines going down the runway, one following another, was described by the ground crew as a "rolling thunder". At this time the Marines had not landed and Danang AFB was unprotected.

After several attacks upon them, it was decided that U.S. Air Force bases needed more protection. The South Vietnamese military seemed incapable of providing security. On March 8, 1965, 3,500 United States Marines were dispatched to South Vietnam. This marked the beginning of the American ground war. U.S. public opinion overwhelmingly supported the deployment. Public opinion, however, was based on the premise that Vietnam was part of a global struggle against communism. In a statement similar to that made to the French almost two decades earlier, Ho Chi Minh warned that if the Americans "want to make war for twenty years then we shall make war for twenty years. If they want to make peace, we shall make peace and invite them to afternoon tea." As former First Deputy Foreign Minister Tran Quang Co has noted, the primary goal of the war was to reunify Vietnam and secure its independence. The policy of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) was not to topple other non-communist governments in South East Asia.

The Marines' assignment was defensive. The initial deployment of 3,500 in March was increased to nearly 200,000 by December. The U.S. military had long been schooled in offensive warfare. Regardless of political policies, U.S. commanders were institutionally and psychologically unsuited to a defensive mission. In May, Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces suffered heavy losses at the Battle of Binh Gia. They were again defeated in June, at the Battle of Dong Xoai. Desertion rates were increasing, and morale plummeted. General William Westmoreland informed Admiral Grant Sharp, commander of U.S. Pacific forces, that the situation was critical. He said, "I am convinced that U.S. troops with their energy, mobility, and firepower can successfully take the fight to the NLF [National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam]." With this recommendation, Westmoreland was advocating an aggressive departure from America's defensive posture and the sidelining of the South Vietnamese. By ignoring ARVN units, the U.S. commitment became open-ended. Westmoreland outlined a three-point plan to win the war:

"Phase 1. Commitment of U.S. (and other free world) forces necessary to halt the losing trend by the end of 1965.

Phase 2. U.S. and allied forces mount major offensive actions to seize the initiative to destroy guerrilla and organized enemy forces. This phase would be concluded when the enemy had been worn down, thrown on the defensive, and driven back from major populated areas.

Phase 3. If the enemy persisted, a period of twelve to eighteen months following Phase 2 would be required for the final destruction of enemy forces remaining in remote base areas."

The plan was approved by Johnson and marked a profound departure from the previous administration's insistence that the government of South Vietnam was responsible for defeating the guerrillas. Westmoreland predicted victory by the end of 1967. Johnson did not, however, communicate this change in strategy to the media. Instead he emphasized continuity. The change in U.S. policy depended on matching the North Vietnamese and the NLF in a contest of attrition and morale. The opponents were locked in a cycle of escalation. The idea that the government of South Vietnam could manage its own affairs was shelved.

Soon the NLF began to engage in small-unit guerrilla warfare, which allowed them to control the pace of the fighting.

It is widely held that the average U.S. serviceman was nineteen years old, as evidenced by the casual reference in a pop song ( 19 by Paul Hardcastle); the figure is cited by Lt. Col. Dave Grossman ret. of the Killology Research Group in his 1995 book On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (p. 265). However, it is disputed by the Vietnam Helicopter Flight Crew Network Website, which claims the average age of MOS 11B personnel was 22. This compares with twenty-six years of age for those who participated in World War II. Soldiers served a one year tour of duty. The average age of the US Military men who died in Vietnam was 22.8 years old. The one-year tour of duty deprived units of experienced leadership. As one observer noted "we were not in Vietnam for 10 years, but for one year 10 times." As a result, training programs were shortened. Some NCO's were referred to as " Shake 'N' Bake" to highlight their accelerated training. Unlike soldiers in World War II and Korea, there were no secure rear areas in which to get rest and relaxation (R'n'R). American troops were vulnerable to attack everywhere they went.

South Vietnam was inundated with manufactured goods. As Stanley Karnow writes, "the main PX, located in the Saigon suburb of Cholon, was only slightly smaller than the New York Bloomingdale's …" The American buildup transformed the economy and had a profound impact on South Vietnamese society. A huge surge in corruption was witnessed. The country was also flooded with civilian specialists from every conceivable field to advise the South Vietnamese government and improve its performance.

Washington encouraged its SEATO allies to contribute troops. Australia, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea, Thailand, and the Philippines all agreed to send troops. Major allies, however, notably NATO nations, Canada and the United Kingdom, declined Washington's troop requests. The U.S. and its allies mounted complex operations, such as operations Masher, Attleboro, Cedar Falls, and Junction City. However, the communist insurgents remained elusive and demonstrated great tactical flexibility.

Meanwhile, the political situation in South Vietnam began to stabilize somewhat with the coming to power of Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky and President Nguyen Van Thieu in 1967. Thieu, mistrustful and indecisive, remained president until 1975. This ended a long series of military juntas that had begun with Diem's assassination. The relative calm allowed the ARVN to collaborate more effectively with its allies and become a better fighting force.

The Johnson administration employed a "policy of minimum candor" in its dealings with the media. Military information officers sought to manage media coverage by emphasizing stories which portrayed progress in the war. Over time, this policy damaged the public trust in official pronouncements. As the media's coverage of the war and that of the Pentagon diverged, a so-called credibility gap developed.

In October 1967 a large anti-war demonstration was held on the steps of the Pentagon. Some protesters were heard to chant, "Hey, hey, LBJ! How many kids did you kill today?" One reason for the increase in the opposition to the Vietnam War was larger draft quotas.

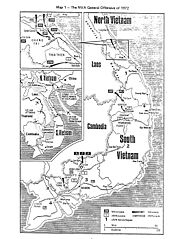

Tet Offensive

Having lured General Westmoreland's forces into the hinterland at Khe Sanh in Quang Tri Province, in January 1968, the PVA and NLF broke the truce that had traditionally accompanied the Tet (Lunar New Year) holiday. They launched the surprise Tet Offensive in the hope of sparking a national uprising. Over 100 cities were attacked, with assaults on General Westmoreland's headquarters and the U.S. embassy in Saigon.

Although the U.S. and South Vietnamese were initially taken aback by the scale of the urban offensive, they responded quickly and effectively, decimating the ranks of the NLF. In the former capital city of Hue, the combined NLF and NVA troops captured the Imperial Citadel and much of the city, which led to the Battle of Hue. During the interim between the capture of the Citadel and end of the "Battle of Hue", the communist insurgent occupying forces massacred several thousand unarmed Hue civilians (estimates vary up to a high of 6000). After the war, North Vietnamese officials acknowledged that the Tet Offensive had, indeed, caused grave damage to NLF forces. But the offensive had another, unintended consequence.

General Westmoreland had become the public face of the war. He was featured on the cover of Time magazine three times and was named 1965's Man of the Year. Time described him as "the sinewy personification of the American fighting man … (who) directed the historic buildup, drew up the battle plans, and infused the … men under him with his own idealistic view of U.S. aims and responsibilities."

In November 1967 Westmoreland spearheaded a public relations drive for the Johnson administration to bolster flagging public support. In a speech before the National Press Club he said that a point in the war had been reached "where the end comes into view." Thus, the public was shocked and confused when Westmoreland's predictions were trumped by Tet. The American media, which had been largely supportive of U.S. efforts, rounded on the Johnson administration for what had become an increasing credibility gap. Despite its military failure, the Tet Offensive became a political victory and ended the career of President Lyndon B. Johnson, who declined to run for re-election. Johnson's approval rating slumped from 48 to 36 percent. As James Witz noted, Tet "contradicted the claims of progress … made by the Johnson administration and the military." The Tet Offensive was the turning point in America's involvement in the Vietnam War. It had a profound impact on domestic support for the conflict. The offensive constituted an intelligence failure on the scale of Pearl Harbour. Journalist Peter Arnett quoted an unnamed officer, saying of Ben Tre that "it became necessary to destroy the village in order to save it". Westmoreland became Chief of Staff of the Army in March, just as all resistance was finally subdued. The move was technically a promotion. However, his position had become untenable because of the offensive and because his request for 200,000 additional troops had been leaked to the media. Westmoreland was succeeded by his deputy Creighton Abrams, a commander less inclined to public media pronouncements.

On May 10, 1968, despite low expectations, peace talks began between the U.S. and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Negotiations stagnated for five months, until Johnson gave orders to halt the bombing of North Vietnam. The Democratic candidate, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, was running against Republican former vice president Richard Nixon. Through an intermediary, Nixon advised Saigon to refuse to participate in the talks until after elections, claiming that he would give them a better deal once elected. Thieu obliged, leaving almost no progress made by the time Johnson left office.

As historian Robert Dallek writes, "Lyndon Johnson's escalation of the war in Vietnam divided Americans into warring camps … cost 30,000 American lives by the time he left office, (and) destroyed Johnson's presidency …" His refusal to send more U.S. troops to Vietnam was Johnson's admission that the war was lost. As Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara noted, "the dangerous illusion of victory by the United States was therefore dead."

Vietnamization, 1969–1973

During the 1968 presidential election, Richard M. Nixon promised "peace with honour". His plan was to build up the ARVN, so that they could take over the defense of South Vietnam (the Nixon Doctrine). The policy became known as " Vietnamization", a term criticized by Robert K. Brigham for implying that, to that date, only Americans had been dying in the conflict. Vietnamization had much in common with the policies of the Kennedy administration. One important difference, however, remained. While Kennedy insisted that the South Vietnamese fight the war themselves, he attempted to limit the scope of the conflict. In pursuit of a withdrawal strategy, Richard Nixon was prepared to employ a variety of tactics, including widening the war.

Nixon also pursued negotiations. Theatre commander Creighton Abrams shifted to smaller operations, aimed at NLF logistics, with better use of firepower and more cooperation with the ARVN. Nixon also began to pursue détente with the Soviet Union and rapprochement with the People's Republic of China. This policy helped to decrease global tensions. Détente led to nuclear arms reduction on the part of both superpowers. But Nixon was disappointed that the PRC and the Soviet Union continued to supply the North Vietnamese with aid. In September 1969, Ho Chi Minh died at age seventy-nine.

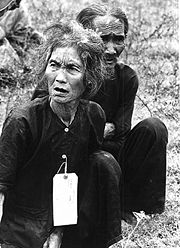

The anti-war movement was gaining strength in the United States. Nixon appealed to the " silent majority" of Americans to support the war. But revelations of the My Lai Massacre, in which U.S. forces went on a rampage and killed civilians, including women and children, provoked national and international outrage. The civilian cost of the war was again questioned when the U.S concluded operation Speedy Express with a claimed bodycount of 10,889 NLF (vietcong) guerillas with only 40 U.S losses; Kevin Buckley writing in Newsweek estimated that perhaps 5,000 of the Vietnamese dead were civilians.

Prince Norodom Sihanouk had proclaimed Cambodia neutral since 1955, but the VPA and NLF used Cambodian soil as a base and Sihanouk tolerated their presence, because he wished to avoid being drawn into a wider regional conflict. Under pressure from Washington, however, he changed this policy in 1969. The VPA and the NLF were no longer welcome. President Nixon took the opportunity to launch a massive secret bombing campaign, called Operation Menu, against their sanctuaries along the border. This violated a long succession of pronouncements from Washington supporting Cambodian neutrality. Richard Nixon wrote to Prince Sihanouk in April 1969 assuring him that the United States respected "the sovereignty, neutrality and territorial integrity of the Kingdom of Cambodia …" Over 14 months, however, approximately 2,750,000 tons of bombs were dropped, more than the total dropped by the Allies in World War II. The bombing was hidden from the American public. In 1970, Prince Sihanouk was deposed by his pro-American prime minister Lon Nol. The country's borders were closed, and the U.S. and ARVN launched incursions into Cambodia to attack VPA/NLF bases and buy time for South Vietnam. The coup against Sihanouk and U.S. bombing destabilized Cambodia and increased support for the Khmer Rouge.

The invasion of Cambodia sparked nationwide U.S. protests. Four students were killed by National Guardsmen at Kent State University during a protest in Ohio, which provoked public outrage in the United States. The reaction to the incident by the Nixon administration was seen as callous and indifferent, providing additional impetus for the anti-war movement.

In 1971 the Pentagon Papers were leaked to The New York Times. The top-secret history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, commissioned by the Department of Defense, detailed a long series of public deceptions. The Supreme Court ruled that its publication was legal.

The ARVN launched Operation Lam Son 719, aimed at cutting the Ho Chi Minh trail in Laos. The offensive was a clear violation of Laotian neutrality, which neither side respected in any event. Laos had long been the scene of a Secret War. After meeting resistance, ARVN forces retreated in a confused rout. They fled along roads littered with their own dead. When they ran out of fuel, soldiers abandoned their vehicles and attempted to barge their way on to American helicopters sent to evacuate the wounded. Many ARVN soldiers clung to helicopter skids in a desperate attempt to save themselves. U.S. aircraft had to destroy abandoned equipment, including tanks, to prevent them from falling into enemy hands. Half of the invading ARVN troops were either captured or killed. The operation was a fiasco and represented a clear failure of Vietnamization. As Karnow noted "the blunders were monumental … The (South Vietnamese) government's top officers had been tutored by the Americans for ten or fifteen years, many at training schools in the United States, yet they had learned little."

In 1971 Australia and New Zealand withdrew their soldiers. The U.S. troop count was further reduced to 196,700, with a deadline to remove another 45,000 troops by February 1972. As peace protests spread across the United States, disillusionment grew in the ranks. Drug use increased, race relations grew tense and the number of soldiers disobeying officers rose. Fragging, or the murder of unpopular officers with fragmentation grenades, increased.

Vietnamization was again tested by the Easter Offensive of 1972, a massive conventional invasion of South Vietnam. The VPA and NLF quickly overran the northern provinces and in coordination with other forces attacked from Cambodia, threatening to cut the country in half. U.S. troop withdrawals continued. But American airpower came to the rescue with Operation Linebacker, and the offensive was halted. However, it became clear that without American airpower South Vietnam could not survive. The last remaining American ground troops were withdrawn in August. But a force of civilian and military advisers remained in place.

The war was the central issue of the 1972 presidential election. Nixon's opponent, George McGovern, campaigned on a platform of withdrawal from Vietnam. Nixon's National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger, continued secret negotiations with North Vietnam's Le Duc Tho. In October 1972, they reached an agreement. However, South Vietnamese President Thieu demanded massive changes to the peace accord. When North Vietnam went public with the agreement's details, the Nixon administration claimed that the North was attempting to embarrass the President. The negotiations became deadlocked. Hanoi demanded new changes. To show his support for South Vietnam and force Hanoi back to the negotiating table, Nixon ordered Operation Linebacker II, a massive bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong. The offensive destroyed much of the remaining economic and industrial capacity of North Vietnam. Simultaneously Nixon pressured Thieu to accept the terms of the agreement, threatening to conclude a bilateral peace deal and cut off American aid. Popularly known as the Christmas Bombings, Operation Linebacker II provoked a fresh wave of anti-war demonstrations.

On January 15, 1973, Nixon announced the suspension of offensive action against North Vietnam. The Paris Peace Accords on "Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam" were signed on January 27, 1973, officially ending direct U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. A cease-fire was declared across North and South Vietnam. U.S. POWs were released. The agreement guaranteed the territorial integrity of Vietnam and, like the Geneva Conference of 1954, called for national elections in the North and South. The Paris Peace Accords stipulated a sixty-day period for the total withdrawal of U.S. forces. "This article," noted Peter Church, "proved … to be the only one of the Paris Agreements which was fully carried out."

The end of the War, 1973-1975

Under Paris Peace Accord, between North Vietnamese Foreign Minister Lê Ðức Thọ and U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and reluctantly signed by South Vietnamese President Thiệu, U.S. military forces withdrew from South Vietnam and prisoners were exchanged. North Vietnam was allowed to continue supplying communist troops in the South, but only to the extent of replacing materials that were consumed. Later that year the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Kissinger and Thọ, but the Vietnamese negotiator declined it saying that a true peace did not yet exist.

The communist leaders had expected that the ceasefire terms would favour their side. But Saigon, bolstered by a surge of U.S. aid received just before the ceasefire went into effect, began to roll back the Vietcong. The communists responded with a new strategy hammered out in a series of meetings in Hanoi in March 1973, according to the memoirs of Trần Văn Trà. As the Vietcong's top commander, Trà participated in several of these meetings. With U.S. bombings suspended, work on the Hochiminh Trail and other logisical structures could proceed unimpeded. Logistics would be upgraded until the North was in a position to launch a massive invasion of the South, projected for the 1975-76 dry season. Trà calculated that this date would be the Hanoi's last opportunity to strike before Saigon's army could be fully trained. A three-thousand-mile long oil pipeline would be built from North Vietnam to Vietcong headquarters in Loc Ninh, about 75 miles northwest of Saigon.

Although McGovern himself was not elected U.S. president, the November 1972 election did return a Democratic majority to both houses of Congress under McGovern's "Come home America" campaign theme. On March 15, 1973, U.S. President Richard Nixon implied that the U.S. would intervene militarily if the communist side violated the ceasefire. Public and congressional reaction to Nixon's trial balloon was unfavorable and in April Nixon appointed Graham Martin as U.S. ambassador to Vietnam. Martin was a second stringer compared to previous U.S. ambassadors and his appointment was an early signal that Washington had given up on Vietnam. During his confirmation hearings in June 1973, Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger stated that he would recommend resumption of U.S. bombing in North Vietnam if North Vietnam launched a major offensive against South Vietnam. On June 4, 1973, the U.S. Senate passed the Case-Church Amendment to prohibit such intervention.

The oil price shock of October 1973 caused significant damage to the South Vietnamese economy. The Vietcong resumed offensive operations when dry season began and by January 1974 it had recaptured the territory it lost during the previous dry season. After two clashes that left 55 South Vietnamese soldiers dead, President Thiệu announced on January 4 that the war had restarted and that the Paris Peace Accord was no longer in effect. There had been over 25,000 South Vietnamese casualties during the ceasefire period.

Gerald Ford took over as U.S. president on August 9, 1974 after President Nixon resigned due to the Watergate scandal. At this time, Congress cut financial aid to South Vietnam from $1 billion a year to $700 million. The U.S. midterm elections in 1974 brought in a new Congress dominated by Democrats who were even more determined to confront the president on the war. Congress immediately voted in restrictions on funding and military activities to be phased in through 1975 and to culminate in a total cutoff of funding in 1976.

The success of the 1973-74 dry season offensive inspired Trà to return to Hanoi in October 1974 and plead for a larger offensive in the next dry season. This time, Trà could travel on a drivable highway with regular fueling stops, a vast change from the days was Hochiminh Trail was a dangerous mountain trek. Giáp, the North Vietnamese defense minister, was reluctant to approved Trà's plan. A larger offensive might provoke a U.S. reaction and interfere with the big push planned for 1976. Trà appealed over Giáp's head to party boss Lê Duẩn, who obtained Politburo approval for the operation.

Trà's plan called for a limited offensive from Cambodia into Phuoc Long Province. The strike was designed to solve local logistical problems, gauge the reaction of South Vietnamese forces, and determine whether the U.S. would return to the fray.

On December 13, 1974, North Vietnamese forces attacked Route 14 in Phouc Long Province. Phouc Binh, the provincial capital, fell on January 6, 1975. Ford desperately asked Congress for funds to assist and re-supply the South before it was overrun. Congress refused. The fall of Phouc Binh and the lack of an American response left the South Vietnamese elite demoralized and corruption grew rampant.

The speed of this success led the Politburo to reassess its strategy. It was decided that operations in the Central Highlands would be turned over to General Văn Tiến Dũng and that Pleiku should be seized, if possible. Before he left for the South, Dũng was addressed by Lê Duẩn: "Never have we had military and political conditions so perfect or a strategic advantage as great as we have now."

By 1975 the South Vietnamese Army faced a well-organized, highly determined and well-funded North Vietnam. Much of the North's material and financial support came from the communist bloc. Within South Vietnam, there was increasing chaos. Their abandonment by the American military had compromised an economy dependent on U.S. financial support and the presence of a large number of U.S. troops. South Vietnam suffered from the global recession which followed the Arab oil embargo.

Campaign 275

On March 10, 1975, General Dung launched Campaign 275, a limited offensive into the Central Highlands, supported by tanks and heavy artillery. The target was Ban Me Thuot, in Daklak Province. If the town could be taken, the provincial capital of Pleiku and the road to the coast would be exposed for a planned campaign in 1976. The ARVN proved incapable of resisting the onslaught, and its forces collapsed on March 11. Once again, Hanoi was surprised by the speed of their success. Dung now urged the Politburo to allow him to seize Pleiku immediately and then turn his attention to Kontum. He argued that with two months of good weather remaining until the onset of the monsoon, it would be irresponsible to not take advantage of the situation.

President Nguyen Van Thieu, a former general, was fearful that his forces would be cut off in the north by the attacking communists; Thieu ordered a retreat. The president declared this to be a "lighten the top and keep the bottom" strategy. But in what appeared to be a repeat of Operation Lam Son 719, the withdrawal soon turned into a bloody rout. While the bulk of ARVN forces attempted to flee, isolated units fought desperately. ARVN General Phu abandoned Pleiku and Kontum and retreated toward the coast, in what became known as the "column of tears". As the ARVN tried to disengage from the enemy, refugees mixed in with the line of retreat. The poor condition of roads and bridges, damaged by years of conflict and neglect, slowed Phu's column. As the North Vietnamese forces approached, panic set in. Often abandoned by their officers, the soldiers, and civilians, were shelled incessantly. The retreat degenerated into a desperate scramble for the coast. By April 1 the "column of tears" was all but annihilated. It marked one of the poorest examples of a strategic withdrawal in modern military history.

On March 20, Thieu reversed himself and ordered Hue, Vietnam's third-largest city, be held at all costs. Thieu's contradictory orders confused and demoralized his officer corps. As the North Vietnamese launched their attack, panic set in, and ARVN resistance withered. On March 22, the VPA opened the siege of Hue. Civilians flooded the airport and the docks hoping for any mode of escape. Some even swam out to sea to reach boats and barges anchored offshore. In the confusion, routed ARVN soldiers fired on civilians to make way for their retreat. On March 31, after a three-day battle, Hue fell. As resistance in Hue collapsed, North Vietnamese rockets rained down on Da Nang and its airport. By March 28, 35,000 VPA troops were poised to attack the suburbs. By March 30, 100,000 leaderless ARVN troops surrendered as the VPA marched victoriously through Da Nang. With the fall of the city, the defense of the Central Highlands and Northern provinces came to an end.

Final North Vietnamese offensive

With the northern half of the country under their control, the Politburo ordered General Dung to launch the final offensive against Saigon. The operational plan for the Ho Chi Minh Campaign called for the capture of Saigon before May 1. Hanoi wished to avoid the coming monsoon and prevent any redeployment of ARVN forces defending the capital. Northern forces, their morale boosted by their recent victories, rolled on, taking Nha Trang, Cam Ranh, and Da Lat.

On April 7, three North Vietnamese divisions attacked Xuan Loc, 40 miles (64 km) east of Saigon. The North Vietnamese met fierce resistance at Xuan Loc from the ARVN 18th Division. For two bloody weeks, severe fighting raged as the ARVN defenders made a last stand to try to block the North Vietnamese advance. By April 21, however, the exhausted garrison surrendered.

An embittered and tearful President Thieu resigned on the same day, declaring that the United States had betrayed South Vietnam. In a scathing attack on the US, he suggested U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had tricked him into signing the Paris peace agreement two years ago, promising military aid which then failed to materialise.

"At the time of the peace agreement the United States agreed to replace equipment on a one-by-one basis," he said. "But the United States did not keep its word. Is an American's word reliable these days?" He continued, "The United States did not keep its promise to help us fight for freedom and it was in the same fight that the United States lost 50,000 of its young men." He left for Taiwan on April 25, leaving control of the government in the hands of General Duong Van Minh. At the same time, North Vietnamese tanks had reached Bien Hoa and turned toward Saigon, brushing aside isolated ARVN units along the way.

By the end of April, the Army of the Republic of South Vietnam had collapsed on all fronts. Thousand of refugees streamed southward, ahead of the main communist onslaught. On April 27, 100,000 North Vietnamese troops encircled Saigon. The city was defended by about 30,000 ARVN troops. To hasten a collapse and foment panic, the VPA shelled the airport and forced its closure. With the air exit closed, large numbers of civilians found that they had no way out.

Fall of Saigon

Chaos, unrest, and panic broke out as hysterical South Vietnamese officials and civilians scrambled to leave Saigon. Martial law was declared. American helicopters began evacuating South Vietnamese, U.S., and foreign nationals from various parts of the city and from the U.S. embassy compound. Operation Frequent Wind had been delayed until the last possible moment, because of U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin's belief that Saigon could be held and that a political settlement could be reached.

Schlesinger announced early in the morning of 29 April 1975 the evacuation from Saigon by helicopter of the last U.S. diplomatic, military, and civilian personnel. Frequent Wind was arguably the largest helicopter evacuation in history. It began on April 29, in an atmosphere of desperation, as hysterical crowds of Vietnamese vied for limited seats. Martin pleaded with Washington to dispatch $700 million in emergency aid to bolster the regime and help it mobilize fresh military reserves. But American public opinion had soured on this conflict halfway around the world.

In the U.S., South Vietnam was perceived as doomed. President Gerald Ford gave a televised speech on April 23, declaring an end to the Vietnam War and all U.S. aid. Frequent Wind continued around the clock, as North Vietnamese tanks breached defenses on the outskirts of Saigon. The song " White Christmas" was broadcast as the final signal for withdrawal. In the early morning hours of April 30, the last U.S. Marines evacuated the embassy by helicopter, as civilians swamped the perimeter and poured into the grounds. Many of them had been employed by the Americans and were left to their fate.

On April 30, 1975, VPA troops overcame all resistance, quickly capturing key buildings and installations. A tank crashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace, and at 11:30 a.m. local time the NLF flag was raised above it. Thieu's successor, President Duong Van Minh, attempted to surrender, but VPA officers informed him that he had nothing left to surrender. Minh then issued his last command, ordering all South Vietnamese troops to lay down their arms.

The Communists had attained their goal: they had toppled the Saigon regime. But the cost of victory was high. In the past decade alone, one Vietnamese in every ten had been a casualty of war—nearly a million and a half killed, three million wounded. Vietnam had been a tormented land, and its ordeal was not over.

Aftermath

Effects on Southeast Asia

Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, fell to the Khmer Rouge on April 17, 1975. The last official American military action in Southeast Asia occurred on May 15, 1975. Forty-one U.S. military personnel were killed when the Khmer Rouge seized a U.S. merchant ship, the SS Mayagüez. The episode became known as the Mayagüez incident.

The Pathet Lao overthrew the royalist government of Laos in December 1975. They established the Lao People's Democratic Republic.

Hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese officials, particularly ARVN officers, were imprisoned in reeducation camps after the Communist takeover. Tens of thousands died and many fled the country after being released. Up to two million civilians left the country, and as many as half of these boat people perished at sea.

On July 2, 1976, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam was declared. After repeated border clashes in 1978, Vietnam invaded Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia) and ousted the Khmer Rouge. As many as two million died during the Khmer Rouge genocide.

Vietnam began to repress its ethnic Chinese minority. Thousand fled and the exodus of the boat people began. In 1979, China invaded Vietnam and the two countries fought a brief border war, known as the Third Indochina War or the Sino-Vietnamese War.

Effect on the United States

In the post-war, Americans struggled to absorb the lessons of the military intervention. As General Maxwell Taylor, one of the principal architects of the war, noted "first, we didn't know ourselves. We thought that we were going into another Korean war, but this was a different country. Secondly, we didn't know our South Vietnamese allies … And we knew less about North Vietnam. Who was Ho Chi Minh? Nobody really knew. So, until we know the enemy and know our allies and know ourselves, we'd better keep out of this kind of dirty business. It's very dangerous."

In the decades since end of the conflict, discussions have ensued as to whether America's withdrawal was a political defeat rather than military defeat. Some have suggested that "the responsibility for the ultimate failure of this policy [America's withdrawal from Vietnam] lies not with the men who fought, but with those in Congress..." Alternatively, the official history of the United States Army noted that "tactics have often seemed to exist apart from larger issues, strategies, and objectives. Yet in Vietnam the Army experienced tactical success and strategic failure … The … Vietnam War('s) … legacy may be the lesson that unique historical, political, cultural, and social factors always impinge on the military … Success rests not only on military progress but on correctly analyzing the nature of the particular conflict, understanding the enemy's strategy, and assessing the strengths and weaknesses of allies. A new humility and a new sophistication may form the best parts of a complex heritage left to the Army by the long, bitter war in Vietnam." U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wrote in a secret memo to President Gerald Ford that "in terms of military tactics, we cannot help draw the conclusion that our armed forces are not suited to this kind of war. Even the Special Forces who had been designed for it could not prevail." Even Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara concluded that "the achievement of a military victory by U.S. forces in Vietnam was indeed a dangerous illusion."

Doubts surfaced as to the effectiveness of large-scale, sustained bombing. As Army Chief of Staff Harold K. Johnson noted, "if anything came out of Vietnam, it was that air power couldn't do the job. Even General William Westmoreland admitted that the bombing had been ineffective. As he remarked, "I still doubt that the North Vietnamese would have relented." The inability to bomb Hanoi to the bargaining table also illustrated another U.S. miscalculation. The North's leadership was composed of hardened communists who had been fighting for independence for thirty years. They had successfully defeated the French, and their tenacity as both nationalists and communists was formidable.

The withdrawal from Vietnam called into question U.S. Army doctrine. Marine Corps General Victor Krulak heavily criticised Westmoreland's attrition strategy, calling it "wasteful of American lives … with small likelihood of a successful outcome." As well, doubts surfaced about the ability of the military to train foreign forces. The defeat also raised disturbing questions about the quality of the advice that was given to successive presidents by the Pentagon.

As the number of troops in Vietnam increased, the financial burden of the war grew. Some of the rarely mentioned consequences of the war were the budget cuts to President Johnson's Great Society programs. As defense spending and inflation grew, Johnson was forced to raise taxes. The Republicans, however, refused to vote for the increases unless a $6 billion cut was made to the administration's social programs.

Almost 3 million Americans served in Vietnam. Between 1965 and 1973, the United States spent $120 billion on the war ($700 billion in 2007 dollars). This resulted in a large federal budget deficit. The war demonstrated that no power, not even a superpower, has unlimited strength and resources. But perhaps most significantly, the Vietnam War illustrated that political will, as much as material might, is a decisive factor in the outcome of conflicts.

In 1977, United States President Jimmy Carter from the Democratic Party issued a pardon for nearly 10,000 draft dodgers.

Other countries' involvement

China

The People's Republic of China's involvement in the Vietnam War began in 1949, when the communists took over the country. The Communist Party of China provided material and technical support to the Vietnamese communists. In the summer of 1962, Mao Zedong agreed to supply Hanoi with 90,000 rifles and guns free of charge. After the launch of "Rolling Thunder", China sent anti-aircraft units and engineering battalions to North Vietnam to repair the damage caused by American bombing, rebuild roads and railroads, and to perform other engineering work. This freed North Vietnamese army units for combat in the South. Between 1965 and 1970, over 320,000 Chinese soldiers served in North Vietnam. The peak came in 1967, when 170,000 served there. Although Chinese assistance was accepted gladly, the North Vietnamese remained distrustful of their larger neighbour because of the historical antipathy between the two nations. China emerged as the principle backer of the Khmer Rouge. The People's Republic of China briefly launched an invasion of Vietnam in 1979 which is considered by most western experts to be a military failure. The two nations continued the border wars in the 1980s which China capturing many Vietnamese islands during the Battle of Hoang Sa and the Spratly Island Skirmish (1988).

South Korea

On the anti-communist side, South Korea had the second-largest contingent of foreign troops in South Vietnam after the United States. South Korea dispatched its first troops in 1964. Large combat battalions began arriving a year later. South Korean troops developed a reputation for effectiveness. Koreans conducted counterinsurgency operations so well that American commanders felt that Korean AOR (area of responsibility) was the safest. This was further supported when Vietcong documents captured after the Tet Offensive warned their compatriots to never engage Koreans until full victory is certain.

Approximately 320,000 South Korean soldiers were sent to Vietnam. As with the United States, soldiers served one year. The maximum number of South Korean troops peaked at 50,000. More than 5,000 South Koreans were killed and 11,000 were injured in the war. All troops were withdrawn in 1973.

Australia & New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand, both close allies of the United States and members of SEATO, sent ground troops to Vietnam. Both nations had gained experience in counterinsurgency and jungle warfare during the Malayan Emergency. Geographically close to Asia, their governments subscribed to the " Domino Theory" of communist expansion and felt that their national security would be threatened if communism spread further in Southeast Asia.

Australia began by sending advisers to Vietnam, the number of which rose steadily until 1965, when combat troops were committed. New Zealand began by sending a detachment of engineers and an artillery battery, and then started sending special forces and regular infantry. Australia's peak commitment was 7,672 combat troops, New Zealand's 552. Most of these soldiers served in the 1st Australian Task Force, a brigade group-type formation, which was based in what was then Phuoc Tuy province, in the vicinity of present-day Ba Ria-Vung Tau Province.

Australia re-introduced conscription to expand its armed forces in the face of significant public opposition to the war.

Several Australian and New Zealand units were awarded U.S. unit citations for their service in South Vietnam, while the last Victoria Crosses—the highest award for bravery in the Commonwealth— awarded to members of the Australian armed forces were for actions in Vietnam.

Philippines

Some 10,450 Filipino troops were dispatched to South Vietnam. They were primarily engaged in medical and other civilian pacification projects. These forces operated under the designation PHLCAAG or Philippines Civil Affairs Assistance Group.

Thailand

Thai Army formations, including the "Queen's Cobra" battalion, saw action in South Vietnam between 1965 and 1971. Thai forces saw much more action in the covert war in Laos between 1964 and 1972, though Thai regular formations there were heavily outnumbered by the irregular "volunteers" of the CIA-sponsored Police Aerial Reconnaissance Units or PARU, who carried out reconnaissance activities on the western side of the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union supplied North Vietnam with medical supplies, arms, tanks, planes, helicopters, artillery, anti-aircraft missiles and other military equipment. Soviet crews fired USSR-made surface-to-air missiles at the B-52 bombers which were the first raiders shot down over Hanoi. Fewer than a dozen Soviet citizens lost their lives in this conflict. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russian officials acknowledged that the Soviet Union had stationed up to 3,000 troops in Vietnam during the war.

North Korea

As a result of a decision of the Korean Workers' Party in October 1966, in early 1967, North Korea sent a fighter squadron to North Vietnam to back up the North Vietnamese 921st and 923rd fighter squadrons defending Hanoi. They stayed through 1968, and 200 pilots were reported to have served. In addition, at least two anti-aircraft artillery regiments were sent as well. North Korea also sent weapons, ammunition and two million sets of uniforms to their comrades in North Vietnam. Kim Il Sung is reported to have told his pilots to "fight in the war as if the Vietnamese sky were their own".

Canada and the ICC

Canadian, Indian and Polish troops (respectively, representatives of NATO, non-aligned states, and the Warsaw Pact) formed the International Control Commission, which was supposed to monitor the 1954 ceasefire agreement. Canada also had citizens serving in Vietnam as part of the U.S. armed forces and harboured American deserters and draft dodgers during the conflict. Canada hosted 30,000–90,000 Americans seeking asylum.

Other countries

Spain sent thirteen soldiers, including doctors.

Nicaragua and Paraguay also offered to send troops to Vietnam in support of the United States.

Use of chemical defoliants

One of the most controversial aspects of the U.S. military effort in Southeast Asia was the widespread use of herbicides between 1961 and 1971. They were used to defoliate large parts of the countryside. These chemicals continue to change the landscape, cause diseases and birth defects, and poison the food chain.

Early in the American military effort it was decided that since the enemy were hiding their activities under triple-canopy jungle a useful first step might be to defoliate certain areas. This was especially true of growth surrounding bases (both large and small) in what became known as Operation Ranch Hand. Corporations like Dow Chemical and Monsanto were given the task of developing herbicides for this purpose. The defoliants, which were distributed in drums marked with colour-coded bands, included the " Rainbow Herbicides"— Agent Pink, Agent Green, Agent Purple, Agent Blue, Agent White, and, most famously, Agent Orange, which included dioxin as a byproduct of its manufacture. About 12 million gallons (45 000 000 L) of Agent Orange were sprayed over Southeast Asia during the American involvement. A prime area of Ranch Hand operations was in the Mekong Delta, where the U.S. Navy patrol boats were vulnerable to attack from the undergrowth at the water's edge.

In 1961 and 1962, the Kennedy administration authorized the use of chemicals to destroy rice crops. Between 1961 and 1967, the U.S. Air Force sprayed 20 million U.S. gallons (75 700 000 L) of concentrated herbicides over 6 million acres (24 000 km²) of crops and trees, affecting an estimated 13% of South Vietnam's land. A 1967 study by the Agronomy Section of the Japanese Science Council concluded that 3.8 million acres (15 000 km²) of foliage had been destroyed, possibly also leading to the deaths of 1,000 peasants and 13,000 head of livestock.

As of 2006, the Vietnamese government estimates that there are over 4,000,000 victims of dioxin poisoning in Vietnam, although the United States government denies any conclusive scientific links between Agent Orange and the Vietnamese victims of dioxin poisoning. In some areas of southern Vietnam dioxin levels remain at over 100 times the accepted international standard.

The U.S. Veterans Administration has listed prostate cancer, respiratory cancers, multiple myeloma, type II diabetes, Hodgkin’s disease, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, soft tissue sarcoma, chloracne, porphyria cutanea tarda, peripheral neuropathy, and spina bifida in children of veterans exposed to Agent Orange. Although there has been much discussion over whether the use of these defoliants constituted a violation of the laws of war, the defoliants were not considered weapons, since exposure to them did not lead to immediate death or incapacitation.

Casualties

The number of military and civilian deaths from 1959 to 1975 is debated. Some reports fail to include the members of South Vietnamese forces killed in the final campaign, or the Royal Lao Armed Forces, thousands of Laotian and Thai irregulars, or Laotian civilians who all perished in the conflict. They do not include the tens of thousands of Cambodians killed during the civil war or the estimated one and one-half to two million that perished in the genocide that followed Khmer Rouge victory, or the fate of Laotian Royals and civilians after the Pathet Lao assumed complete power in Laos.

In 1995, the Vietnamese government reported that its military forces, including the NLF, suffered 1.1 million dead and 600,000 wounded during Hanoi's conflict with the United States. Civilian deaths were put at two million in the North and South, and economic reparations were expected. Hanoi concealed the figures during the war to avoid demoralizing the population.

Popular culture

The Vietnam War has been featured heavily in television and films. The war also influenced a generation of musicians and songwriters. The band Country Joe and The Fish recorded "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-To-Die Rag" in 1965, and it became one of the most influential anti-Vietnam protest anthems. The musical Miss Saigon focuses on the end of the war and its aftermath. In cinema, noted films that have shaped the popular conception of the war include Apocalypse Now, Platoon, The Deer Hunter , Hamburger Hill, Full Metal Jacket, Good Morning, Vietnam, Born on the Fourth of July, the Rambo films and We Were Soldiers. It serves as the setting for numerous video games, such as Conflict: Vietnam.