History of Anglo-Saxon England

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: British History 1500 and before (including Roman Britain)

The History of Anglo-Saxon England covers the history of early medieval England from the end of Roman Britain and the establishment of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the 5th century until the Conquest by the Normans in 1066. The 5th and 6th centuries are known archaeologically as Sub-Roman Britain, or in popular history as the "Dark Ages"; from the 6th century larger distinctive kingdoms are developing, still known to some as the Heptarchy; the arrival of the Vikings at the end of the 8th century brought many changes to Britain, and relations with the continent were important right up to the 'end' of Anglo-Saxon England, traditionally held to be the Norman Conquest.

Migration and Formation of Kingdoms (400-600)

It is very difficult to establish a coherent chronology of events from Rome's departure from Britain, to the establishment of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The story of the Roman departure as told by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae is dubious except as documenting Medieval legend.

The archaeological records of the final decades of Roman rule show undeniable signs of decay, in stagnant urban and villa life. Coins minted past 402 are rare. So when Constantine III was declared Emperor by his troops in 407, and crossed the channel with the remaining units of the British garrison, effectively Roman Britain ended. Britain was left defenceless, and Constantine was eventually killed in battle. In 410, Emperor Honorius told the Romano-British to look to their own defence, yet in the mid 5th century the Romano-British still felt they could appeal to the consul Aetius for help against invaders.

Various myths and legends surround the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons, some based on documentary evidence, some far less so. Four main literary sources provide the evidence. Gildas' 'The Ruin of Britain' (c. 540) is polemical, and more concerned with criticising British kings than accurately describing events. Bede's 'Ecclesiastical History of the English People' is based in part on Gildas, though brings in other evidence. However, this was written in the early 8th century, some time after events. Later still is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which is in part based on Bede, but also brings in legends regarding the foundation of Wessex.

Other evidence can be brought in to aid the literary sources. It is interesting to note that the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Kent, Bernicia, Deira and Lindsey all retained Celtic names, which would suggest political continuity. Contrastingly, the more westerly kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia show little sign of following existing boundaries. Archaeologically, following burial patterns and land usage allows us to follow Anglo-Saxon settlement, though it is possible that the British were adopting Anglo-Saxon practice. Analysis of human remains unearthed at an ancient cemetery near Abingdon, England, indicates that Saxon immigrants and native Britons lived side by side. There is much academic debate as to whether the Anglo-Saxon migrants replaced, or merged with, the Romano-British people who inhabited southern and eastern Britain.

Already from the 4th century AD, Britons had migrated across the English Channel and started to settle in the western part ( Armorica) of Gaul (France), forming Brittany. Others may have migrated to northern Spain. The migration of the British to the continent and the Anglo-Saxons to Britain, should be considered in the context of wider European migrations. However, some doubt, based on limited genetic work, has been cast on the extent of Anglo-Saxon migration to Britain.

Though one cannot be sure of dates, places or people involved, it does seem that in 495, at the Battle of Mount Badon (possibly Badbury rings, Latin Mons Badonicus, Welsh Mynydd Baddon), the Britons inflicted a severe defeat on the Anglo-Saxons. Archaeological evidence, coupled with the questionable source Gildas, would suggest that the Anglo-Saxon migration was stemmed for a while.

Heptarchy and Christianisation (600-800)

Christianisation of Anglo-Saxon England began around AD 600, influenced by Celtic Christianity from the north-west and by the Roman Catholic Church from the south-east. The first Archbishop of Canterbury, Augustine took office in 597. In 601, he baptised the first Anglo-Saxon king, Aethelbert of Kent. The last pagan Anglo-Saxon king, Penda of Mercia, died in 655. The Anglo-Saxon mission on the continent took off in the 8th century, leading to the Christianisation of practically all of the Frankish Empire by AD 800.

Throughout the 7th and 8th century power fluctuated between the larger kingdoms. Bede records Aethelbert of Kent as being dominant at the close of the 6th century, but power seems to have shifted northwards to the kingdom of Northumbria, which was formed from the amalgamation of Bernicia and Deira. Edwin probably held dominance over much of Britain, though Bede's Northumbria bias should be kept in mind. Succession crises meant Northumbrian hegemony was not constant, and Mercia remained a very powerful kingdom, especially under Penda. Two defeats essentially ended Northumbrian dominance: the Battle of the Trent (679) against Mercia, and Nechtanesmere (685) against the Picts.

The so-called 'Mercian Supremacy' dominated the 8th century, though again was not constant. Aethelbald and Offa, the two most powerful kings, achieved high status; indeed, Offa was considered the overlord of south Britain by Charlemagne. That Offa could summon the resources to build Offa's Dyke is testament to his power. However, a rising Wessex, and challenges from smaller kingdoms, kept Mercian power in check, and by the end of the 8th century the 'Mercian Supremacy', if it existed at all, was over.

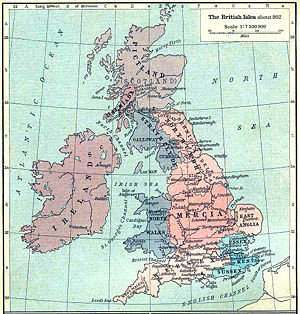

This period has been described as the Heptarchy, though this term has now fallen out of academic use. The word arose on the basis that the seven kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia, Kent, East Anglia, Essex, Sussex and Wessex were the main polities of south Britain. More recent scholarship has shown that a number of other kingdoms were politically important across this period: Hwicce, Magonsaete, Lindsey and Middle Anglia. See also the non-Anglo-Saxon kingdoms such as Strathclyde, Rheged

The Viking challenge and the rise of Wessex (9th century)

793 is the date given by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the first Viking attack in Britain, at Lindisfarne monastery. However, by then the Vikings were almost certainly well established in Orkney and Shetland, and it is probable that many other non-recorded raids occurred before this. Records do show the first Viking attack on Iona taking place in 794, The arrival of the Vikings, in particular their Great Heathen Army, was to seriously upset the political and social geography of Britain and Ireland. Alfred the Great's victory at Edington in 878 stemmed the Viking attack; however, by this time Northumbria had devolved into Bernicia and a Viking kingdom, Mercia had been split down the middle, and East Anglia ceased to exist as an Anglo-Saxon polity. The Vikings had similar effects on the various kingdoms of the Irish, Scots, Picts and (to a lesser extent) Welsh. Certainly in North Britain the Vikings were one reason behind the formation of the Kingdom of Alba, which eventually evolved into Scotland.

After a time of plunder and raids, the Vikings began to settle in England. An important Viking centre was York, called Jorvik by the Vikings. Various alliances between the Viking Kingdom of York and Dublin rose and fell. Danish and Norwegian settlement made enough of an impact to leave significant traces in the English language; many fundamental words in modern English are derived from Old Norse, though of the 100 most used words in English the vast majority are Old English in origin. Similarly, many place-names in areas of Danish and Norwegian settlement have Scandinavian roots (e.g. Sutherland).

An important development of the 9th century was the rise of the Kingdom of Wessex. Though it was somewhat of a roller-coaster journey, the West Saxon kings came, by the end of Alfred's reign (899), to rule what had previously been Wessex, Sussex and Kent. Cornwall (Kernow) was subject to West Saxon dominance, and several kings of the more southerly Welsh kingdoms recognised Alfred as their overlord, as did western Mercia under Alfred's son-in-law Æthelred.

Formation of England (10th century)

Alfred of Wessex died in 899 and was succeeded by his son Edward the Elder. Edward, and his brother in law Æthelred of (what was left of) Mercia, began a program of expansion, building forts and towns on an Alfredian model. On Æthelred's death his wife (Edward's sister) Æthelflæd ruled as 'Lady of the Mercians', and continued expansion. It seems Edward had his son Æthelstan brought up in the Mercian court, and on Edward's death Athelstan succeeded to the Mercian kingdom, and, after some uncertainty, Wessex.

Æthelstan continued the expansion of his father and aunt, and was the first king to achieve direct rulership of what we would now consider 'England'. Certainly the titles attributed to him in charters and on coins suggest a widespread dominance. His expansion aroused ill-feeling among the other kingdoms of Britain, and he faced a combined Scottish-Viking army at the Battle of Brunanburh. His victory there, recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle with a poem, was one of the major steps on the road to the formation of England.

However, England was not a certainty, and indeed under Æthelstan's successors Edmund, Eadred and Edwy the kingdom broke up and was reformed numerous times. Nonetheless, Edgar, who eventually ruled the same expanse as Athelstan, seems to have consolidated the kingdom, and by the time of the rule of his son Æthelred (the Unready) England seems to have (almost) secured itself as a kingdom.

The 10th century saw important developments across Western Europe. Carolingian authority was in decline by the mid-10th century in West Francia (France), and eventually collapsed to be replaced by the weak House of Capet. In East Francia a Saxon dynasty came to power, and its kings began taking the title of Holy Roman Emperor. Interestingly, Anglo-Saxon England was probably the most 'developed' kingdom of the period; one has only to look at the way coinage was managed in the period to realise that 10th century Anglo-Saxon kings wielded far greater royal authority than their European counterparts.

England under the Danes and the Norman Conquest (978-1066)

The end of the 10th century saw renewed Scandinavian interest in England. Aethelred ruled a long reign, but ultimately lost his kingdom to Sweyn of Denmark, though he recovered it following the latter's death. However, Æthelred's son Edmund II Ironside died shortly afterwards, allowing Canute, Sweyn's son, to become king of England, one part of a mighty empire stretching across the North Sea. It was probably in this period that the Viking influence on English culture became engrained.

Rule over England fluctuated between the descendants of Aethelred and Canute for the first half of the 11th century. Ultimately this resulted in the well-known situation of 1066, where several people had a claim to the English throne. Harold Godwinson became king, in all likelihood appointed by Edward the Confessor on his deathbed. However, William of Normandy, a descendant of Aethelred and Canute's wife Emma, and Harald of Norway (aided by Harold Godwin's estranged brother Tostig) all had a claim. Perhaps the strongest claim went to Edgar the Atheling, whose minority prevented him from playing a larger part in the struggles of 1066, though he was made king for a short time by the English Witan.

Invasion was the result of this situation. Harold Godwinson defeated Harald of Norway and Tostig at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, but fell in battle against William of Normandy at Hastings. William began a program of consolidation in England, being crowned on Christmas Day, 1066. However, his authority was always under threat in England, and the little space spent on Northumbria in Domesday Book is testament to the troubles there during William's reign.