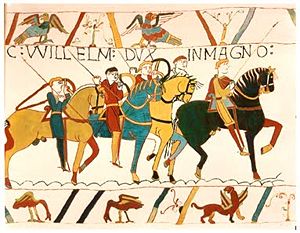

Norman conquest of England

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: British History 1500 and before (including Roman Britain)

The Norman conquest of England began in 1066 AD with the invasion of the Kingdom of England by the troops of William, Duke of Normandy ("William the Conqueror"), and his victory at the Battle of Hastings. This resulted in Norman control of England, which was firmly established during the next few years. The Norman Conquest was a pivotal event in English history for several reasons. It largely removed the native ruling class, replacing it with a foreign, French-speaking monarchy, aristocracy and clerical hierarchy. This in turn brought about a transformation of the English language and the culture of England. By subjecting the country to rulers originating in France it linked England more closely with continental Europe, while lessening Scandinavian influence, and set the stage for a rivalry with France that would continue intermittently for more than eight centuries. It also had important consequences for the rest of the British Isles, paving the way for further Norman conquests in Wales and Ireland, and the extensive penetration of the aristocracy of Scotland by Norman and other French-speaking families.

Origins

Normandy is a region in northern France which in the years prior to 1066 experienced extensive Viking settlement. In 911, French Carolingian ruler Charles the Simple had allowed a group of Vikings, under their leader Rollo, to settle in northern France with the idea that they would provide protection along the coast against future Viking invaders. This proved successful, and the Vikings in the region became known as the Northmen from which Normandy is derived. The Normans quickly adapted to the indigenous culture, renouncing paganism and converting to Christianity. They adopted the langue d'oïl of their new home and added features from their own Norse language, transforming it into the Norman language. They further blended into the culture by intermarrying with the local population. They also used the territory granted them as a base to extend the frontiers of the Duchy to the west, annexing territory including the Bessin, the Cotentin Peninsula and the Channel Islands.

In 991 the King of England Aethelred II married Emma, the daughter of the Duke of Normandy. Their son Edward the Confessor, who had spent many years in exile in Normandy, succeeded to the English throne in 1042. This led to the establishment of a powerful Norman interest in English politics, as Edward drew heavily on Norman support, bringing in Norman courtiers, soldiers and clerics and appointing Normans to positions of power, particularly in the Church. Childless and embroiled in conflict with the formidable Godwin, Earl of Wessex and his sons, Edward may also have encouraged Duke William of Normandy's ambitions for the English throne.

When King Edward died at the beginning of 1066, the lack of a clear heir led to a disputed succession in which several contenders laid claim to the throne of England. Edward's immediate successor was the Earl of Wessex Harold Godwinson, the richest and most powerful of the English aristocracy, who was elected king by the Witenagemot of England. However, he was at once challenged by two powerful neighbouring rulers. Duke William claimed that he had been promised the throne by King Edward and that Harold had sworn agreement to this. Harald III of Norway, commonly known as Harald Hardraada, also contested the succession. His claim to the throne was based on a supposed agreement between his predecessor Magnus I of Norway, and the earlier Danish King of England Harthacanute, whereby if either died without heir, the other would inherit both England and Norway. Both William and Harald at once set about assembling troops and ships for an invasion.

Tostig and Harald

In spring 1066 Harold's estranged and exiled brother Tostig Godwinson raided in southeastern England with a fleet he had recruited in Flanders, later joined by other ships from Orkney. Threatened by Harold's fleet, Tostig moved north and raided in East Anglia and Lincolnshire, but he was driven back to his ships by the brothers Edwin, Earl of Mercia, and Morcar, Earl of Northumbria. Deserted by most of his followers, he withdrew to Scotland, where he spent the summer recruiting fresh forces. King Harald of Norway invaded northern England in early September, leading a fleet of over 300 ships carrying perhaps 15,000 men. Harald's army was further augmented by the forces of Tostig, who threw his support behind Harald's bid for the throne. Advancing on York, the Norwegians occupied the city after defeating a northern English army under Edwin and Morcar on 20 September at the Battle of Fulford. Harold had spent the summer on the south coast with a large army and fleet waiting for William to invade, but on 8 September, after his food supplies were exhausted, he had dismissed them. Learning of the Norwegian invasion, he rushed north, gathering forces as he went, and took the Norwegians by surprise, defeating them in the exceptionally bloody Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September. Harald of Norway and Tostig were killed, and the Norwegians suffered such horrific losses that only 24 ships were required to carry away the survivors. The English victory came at great cost, however, as Harold's army was left in a battered and weakened state.

Norman invasion

Meanwhile William assembled an invasion fleet and an army of unknown size in 1066.

William gathered his ships at Saint-Valery-sur-Somme. His army was ready to cross by 12 August; however, unfavourable weather delayed the crossing, so his army did not arrive in the south of England until a few days after Harold's victory over the Norwegians. After landing in Sussex on September 28, William's army assembled a prefabricated wooden castle near Hastings and used the camp as a base.

Marching south at the news of William's landing, Harold paused briefly at London to gather more troops, then advanced to meet William. They fought at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October. Harold was killed, along with his brothers Earl Gyrth and Earl Leofwine, and the English army fled.

After his victory at Hastings, William expected to receive the submission of the surviving English leaders, but instead Edgar Atheling was proclaimed king by the Witenagemot, with the support of Earls Edwin and Morcar, Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Aldred, Archbishop of York. William, who had received reinforcements from across the English Channel, therefore advanced, marching through Kent to London. He defeated an English force which attacked him at Southwark, but he was unable to storm London Bridge and therefore sought to reach the capital by a more circuitous route. He marched west to link up with another Norman force near Dorking, Surrey. The combined armies then moved up the Thames valley to cross the river at Wallingford, Oxfordshire. While there, he received the submission of Stigand. William then travelled northeast along the Chilterns, before advancing towards London from the northwest. Having failed to muster an effective military response, Edgar's leading supporters lost their nerve, and the English leaders surrendered to William at Berkhamstead, Hertfordshire. William was acclaimed King of England and crowned by Aldred on 25 December 1066, in Westminster Abbey.

English resistance

Despite this submission, local resistance continued to erupt for several years. In 1067 rebels in Kent launched an abortive attack on Dover Castle in combination with Eustace II of Boulogne. In the same year the Shropshire landowner Eadric the Wild, in alliance with the Welsh rulers of Gwynedd and Powys, raised a revolt in western Mercia, attacking the Norman castle at Hereford. In 1068 William besieged rebels in Exeter, including Harold's mother Gytha; after suffering heavy losses William managed to negotiate the town's surrender. Later in the year Edwin and Morcar raised a revolt in Mercia, while Earl Gospatric led a rising in Northumbria, which had not yet been occupied by the Normans. These rebellions rapidly collapsed as William moved against them, building castles and installing garrisons as he had already done in the south. Edwin and Morcar again submitted, while Gospatric fled to Scotland, as did Edgar the Atheling and his family, who may have been involved in these revolts. Meanwhile Harold's sons, who had taken refuge in Ireland, raided Somerset, Devon and Cornwall from the sea. Early in 1069 the newly installed Norman Earl of Northumbria Robert de Comines and several hundred soldiers accompanying him were massacred at Durham, igniting a widespread Northumbrian rebellion, which was joined by Edgar, Gospatric and other rebels who had taken refuge in Scotland. The castellan of York, Robert fitzRichard, was defeated and killed, and the rebels besieged the Norman castles at York. William hurried with an army from the south, took the rebels by surprise and defeated them in the streets of the city, bringing the revolt to an end. A subsequent local uprising was crushed by the garrison of York. Harold's sons launched a second raid from Ireland but were defeated in Devon by Norman forces under Count Brian, a son of Eudes, Count of Penthièvre.

In the late summer of 1069 a large fleet sent by Sweyn II of Denmark arrived off the coast of England, sparking a new wave of rebellions across the country. After abortive attempted raids in the south, the Danes joined forces with a new Northumbrian uprising, which was also joined by Edgar, Gospatric and the other exiles from Scotland as well as Earl Waltheof. The combined Danish and English forces defeated the Norman garrison at York, seized the castles and took control of Northumbria, although a raid into Lincolnshire led by Edgar was defeated by the Norman garrison of Lincoln. Meanwhile resistance flared up again in western Mercia, where the forces of Eadric the Wild, together with his Welsh allies and further rebel forces from Cheshire, attacked the castle at Shrewsbury. In the south-west rebels from Devon and Cornwall attacked the Norman garrison at Exeter, but were repulsed by the defenders and scattered by a Norman relief force under Count Brian. Other rebels from Dorset and Somerset besieged Montacute Castle but were defeated by a Norman army gathered from London, Winchester and Salisbury under Geoffrey of Coutances.

Meanwhile William advanced northwards, attacking the Danes, who had moored for the winter south of the Humber in Lincolnshire, and driving them back to the north bank. Leaving Robert of Mortain in charge in Lincolnshire, he turned west and defeated the Mercian rebels in battle at Stafford. When the Danes again crossed to Lincolnshire the Norman forces there again drove them back across the Humber. William advanced into Northumbria, defeating an attempt to block his crossing of the swollen River Aire at Pontefract. The Danes again fled at his approach, and he occupied York. He bought off the Danes, who agreed to leave England in the spring, and through the winter of 1069–70 his forces systematically devastated Northumbria in the Harrying of the North, subduing all resistance. In the spring of 1070, having secured the submission of Waltheof and Gospatric, and driven Edgar and his remaining supporters back to Scotland, William returned to Mercia, where he based himself at Chester and crushed all remaining resistance in the area before returning to the south. Sweyn II of Denmark arrived in person to take command of his fleet and renounced the earlier agreement to withdraw, sending troops into the Fens to join forces with English rebels led by Hereward, who were based on the Isle of Ely. Soon, however, Sweyn accepted a further payment of Danegeld from William and returned home.

After the departure of the Danes the Fenland rebels remained at large, protected by the marshes, and early in 1071 there was a final outbreak of rebel activity in the area. Edwin and Morcar again turned against William, and while Edwin was soon betrayed and killed, Morcar reached Ely, where he and Hereward were joined by exiled rebels who had sailed from Scotland. William arrived with an army and a fleet to finish off this last pocket of resistance. After some costly failures the Normans managed to construct a pontoon to reach the Isle of Ely, defeated the rebels at the bridgehead and stormed the island, marking the effective end of English resistance.

Many of the Norman sources which survive today were written in order to justify their actions, in response to Papal concern about the treatment of the native English by their Norman conquerors during this period.

Control of England

Once England had been conquered, the Normans faced many challenges in maintaining control. The Anglo-Norman-speaking Normans were few in number compared to the native English population. Historians estimate the number of Norman knights at between 5,000 and 8,000. The Normans overcame this numerical deficit by adopting innovative methods of control.

First, unlike the Danes, who had exacted taxes but generally did not supplant English landholders, the Normans expected and received from William lands and titles in return for their service in the invasion. Therefore, perhaps for the first time in English history, William claimed ultimate possession of virtually all the land in England and asserted the right to dispose of it as he saw fit. Henceforth, all land was "held" from the King. Initially, William confiscated the lands of all English lords who had fought and died with Harold and redistributed most of them to his Norman supporters (though some families were able to "buy back" their property and titles by petitioning William). These initial confiscations led to revolts, which resulted in more confiscations, in a cycle that continued virtually unbroken for five years after the Battle of Hastings. To put down and prevent further rebellions (and to defend against increasingly rare Viking attacks), the Normans constructed a variety of forts and castles (such as the motte-and-bailey) on an unprecedented scale.

Even after active resistance to his rule had died down, William and his barons continued to use their positions to extend and consolidate Norman control of the country. For example, if an English landholder died without issue, the King (or in the case of lower-level landholders, one of his barons) could designate the heir, and often chose a successor from Normandy. William and his barons also exercised tighter control over inheritance of property by widows and daughters, often forcing marriages to Normans. In this way the Normans displaced the native aristocracy and took control of the upper ranks of society. By 1086, when the Domesday Book was completed, French names predominated even at the lower levels of the aristocracy.

A measure of William's success in taking control is that, from 1072 until the Capetian conquest of Normandy in 1204, William and his successors were largely absentee rulers. For example, after 1072, William spent more than 75% of his time in France rather than in England. While he needed to be personally present in Normandy to defend the realm from foreign invasion and put down internal revolts, he was able to set up royal administrative structures that enabled him to rule England from a distance, by "writ". Kings were not the only absentees since the Anglo-Norman barons would use the practice too. Keeping the Norman lords together and loyal as a group was just as important, since any friction could give the native English a chance to oust their minority Anglo-French-speaking lords. Odo of Bayeux, half brother of William, for example was eventually stripped of his property holdings after a series of unsanctioned acquisitions and fraudulent activities, a move which threatened to destabilise the purported authority of Norman land holdings. One way William accomplished this cohesion was by giving out land in a piece-meal fashion and punishing unauthorised holdings. A Norman lord typically had property spread out all over England and Normandy, and not in a single geographic block. Thus, if the lord tried to break away from the king, he could only defend a small number of his holdings at any one time.

Over the longer range the same policy greatly facilitated contacts between the nobility of different regions and encouraged the nobility to organize and act as a class, rather than on an individual or regional base which was the normal way in other feudal countries. The existence of a strong centralized monarchy encouraged the nobility to form ties with the city dwellers, which was eventually manifested in the rise of English parliamentarianism.

Significance

Language

One of the most obvious changes was the introduction of Anglo-Norman, a northern dialect of Old French, as the language of the ruling classes in England, displacing Old English. Even after the decline of Norman, French retained the status of a prestige language for nearly 300 years and has had (with Norman) a significant influence on the language, which is easily visible in Modern English.

Governmental systems

Before the Normans arrived, Anglo-Saxon England had one of the most sophisticated governmental systems in Western Europe. All of England was divided into administrative units called shires (shares) of roughly uniform size and shape, which were run by officials known as "shire reeve" or " sheriff". The shires tended to be somewhat autonomous and lacked coordinated control. English government made heavy use of written documentation which was unusual for kingdoms in Western Europe and made for more efficient governance than word of mouth.

The English developed permanent physical locations of government. Most medieval governments were always on the move, holding court wherever the weather and food or other matters were best at the moment. This practice limited the potential size and sophistication of a government body to whatever could be packed on a horse and cart, including the treasury and library. England had a permanent treasury at Winchester, from which a permanent government bureaucracy and document archive begun to grow.

This sophisticated medieval form of government was handed over to the Normans and grew stronger. The Normans centralised the autonomous shire system. The Domesday Book exemplifies the practical codification which enabled Norman assimilation of conquered territories through central control of a census. It was the first kingdom-wide census taken in Europe since the time of the Romans, and enabled more efficient taxation of the Norman's new realm.

Systems of accounting grew in sophistication. A government accounting office called the exchequer was established by Henry I; from 1150 onward this was located in Westminster.

Anglo-Norman and French relations

After the conquest, Anglo-Norman and French political relations became very complicated and somewhat hostile. The Normans retained control of the holdings in Normandy and were thus still vassals to the King of France. At the same time, they were their equals as King of England. On the one hand they owed fealty to the King of France, and on the other hand they did not, because they were peers. In the 1150s, with the creation of the Angevin Empire, the Plantagenets controlled half of France and all of England, dwarfing the power of the Capetians. Yet the Normans were still technically vassals to France. A crisis came in 1204 when French King Philip II seized all Norman and Angevin holdings in mainland France except Gascony. This led to the Hundred Years War when Anglo-Norman English kings tried to regain their dynastic holdings in France.

During William's lifetime, his vast land gains were a source of great alarm to the King of France and the counts of Anjou and Flanders. Each did his best to diminish Normandy's holdings and power, leading to years of conflict in the region.

English cultural development

A direct consequence of the invasion was the near total elimination of the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy and the loss of English control over the Catholic Church in England. As William subdued rebels, he confiscated their lands and gave them to his Norman supporters. By the time of the Domesday Book, only two English landowners of any note had survived the displacement. By 1096 no church See or Bishopric was held by any native Englishman; all were held by Normans. No other medieval European conquest of Christians by Christians had such devastating consequences for the defeated ruling class. Meanwhile, William's prestige among his followers increased tremendously because he was able to award them vast tracts of land at little cost to himself. His awards also had a basis in consolidating his own control; with each gift of land and titles, the newly-created feudal lord would have to build a castle and subdue the natives. Thus was the conquest self-perpetuating.

Legacy

As early as the 12th century the Dialogue concerning the Exchequer attests to considerable intermarriage between native English and Norman immigrants. Over the centuries, particularly after 1348 when the Black Death pandemic carried off a significant number of the English nobility, the two groups largely intermarried and became barely distinguishable.

The Norman conquest was the last successful conquest of England, although some historians identify the Glorious Revolution of 1688 as the most recent successful invasion from the continent. Major invasion attempts were launched by the Spanish in 1588 and the French in 1744 and 1759, but in each case the combined impact of the weather and the attacks of the Royal Navy on their escort fleets thwarted the enterprise without the invading army even putting to sea. Invasions were also prepared by the French in 1805 and Nazi Germany in 1940, but these were abandoned after preliminary operations failed to overcome Britain's naval and, in the latter case, air defences. Various brief raids on British coasts were successful within their limited scope, such as those launched by the French during the Hundred Years War, the Spanish landing in Cornwall in 1595, the Dutch raid on the Medway shipyards in 1667 and raids by Barbary pirates in the 17th and 18th centuries.