Marshall Plan

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Recent History; World War II

The Marshall Plan (from its enactment, officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was the primary plan of the United States for rebuilding and creating a stronger foundation for the allied countries of Europe, and repelling communism after World War II. The initiative was named for Secretary of State George Marshall and was largely the creation of State Department officials, especially William L. Clayton and George F. Kennan.

The reconstruction plan developed at a meeting of the participating European states was established on July 12, 1947. The Marshall Plan offered the same aid to the USSR and its allies, but they did not accept it due to the diplomatic and political pressure the US universally applied in return for its aid. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in July 1947. During that period some USD 13 billion in economic and technical assistance were given to help the recovery of the European countries that had joined in the Organization for European Economic Co-operation. Aid had been given to many European countries before the Marshall Plan since 1945, again with the accompanying political pressure (France, for example, was required to show Hollywood films in return for its receipt of American financial assistance, crippling the French film industry).

By the time the plan had come to completion, the economy of every participant state, with the exception of Germany, had grown well past pre-war levels. Over the next two decades, many regions of Western Europe would enjoy unprecedented growth and prosperity. The Marshall Plan has also long been seen as one of the first elements of European integration, as it erased tariff trade barriers and set up institutions to coordinate the economy on a continental level.

In recent years historians have questioned both the underlying motivation and the overall effectiveness of the Marshall Plan. Some historians contend that the benefits of the Marshall Plan actually resulted from new laissez-faire policies that allowed markets to stabilize through economic growth. It is now acknowledged that the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, which helped millions of refugees from 1944 to 1947, also laid the foundation for European postwar recovery.

Before the Marshall Plan

After six years of war, much of Europe was devastated with millions killed and injured. Fighting had occurred throughout much of the continent, encompassing an area far larger than that in World War I. Sustained aerial bombardment meant that most major cities had been badly damaged, with industrial production especially hard-hit. Many of the continent's greatest cities, including Warsaw and Berlin, lay in ruins. Others, such as London and Rotterdam, had been severely damaged. The region's economic structure was ruined, and millions had been made homeless. Although the Dutch famine of 1944 had abated with an influx of aid, the general devastation of agriculture had led to conditions of starvation in several parts of the continent, which was to be exacerbated by the particularly harsh winter of 1946–1947 in northwestern Europe. Especially damaged was transportation infrastructure, as railways, bridges, and roads had all been heavily targeted by air strikes, while much merchant shipping had been sunk. Although most small towns and villages in Western Europe had not suffered as much damage, the destruction of transportation left them economically isolated. None of these problems could be easily remedied, as most nations engaged in the war had exhausted their treasuries in its execution.

After World War I, the European economy had also been greatly damaged, and a deep recession lasting well into the 1920s had led to instability and a general global downturn. The United States, despite a resurgence of isolationism, had attempted to promote European growth, mainly through partnerships with the major American banks. When Germany was unable to pay its reparations, the Americans also intervened by extending a large loan to Germany, a debt the Americans were left with when the US joined the war in 1941.

In Washington, there was a consensus that the events after World War I should not be repeated. The State Department under Harry S. Truman and Robert Rosemont was dedicated to pursuing an activist foreign policy, but the Congress was somewhat less interested. Originally, it was hoped that little would need to be done to rebuild Europe and that the United Kingdom and France, with the help of their colonies, would quickly rebuild their economies. By 1947 there was still little progress, however. A series of cold winters aggravated an already poor situation. The European economies did not seem to be growing as high unemployment and food shortages led to strikes and unrest in several nations. In 1947 the European economies were still well below their pre-war levels and were showing few signs of growth. Agricultural production was 83% of 1938 levels, industrial production was 88%, and exports only 59%.

The shortage of food was one of the most acute problems. Before the war, Western Europe had depended on the large food surpluses of Eastern Europe, but these routes were largely cut off by the Iron Curtain. The situation was especially bad in Germany where according to Alan S. Milward in 1946–47 the average kilocalorie intake per day was only 1,800, an amount insufficient for long-term health. Other sources state that the kilocalorie intake in those years varied between as low as 1,000 and 1,500 (see Eisenhower and German POWs). William Clayton reported to Washington that "millions of people are slowly starving." As important for the overall economy was the shortage of coal, aggravated by the cold winter of 1946–47. In Germany, homes went unheated and hundreds froze to death. In the United Kingdom, the situation was not as severe, but domestic demand meant that industrial production came to a halt. The humanitarian desire to end these problems was one motivation for the plan.

Germany received many offers from Western European nations to trade food for desperately needed coal and steel. Neither the Italians nor the Dutch could sell the vegetables that they had previously sold in Germany, with the consequence that the Dutch had to destroy considerable proportions of their crop. Denmark offered 150 tons of lard a month; Turkey offered hazelnuts; Norway offered fish and fish oil; Sweden offered considerable amounts of fats. The Allies were however not willing to let the Germans trade. In view of increased concerns by General Lucius D. Clay and the Joint Chief of Staff over growing communist influence in Germany, as well as of the failure of the rest of the European economy to recover without the German industrial base on which it previously had been dependent, in the summer of 1947 Secretary of State General George Marshall, citing "national security grounds" was finally able to convince President Harry S. Truman to rescind the punitive U.S. occupation directive JCS 1067, and replace it with JCS 1779. In July 1947 JCS 1067, which had directed the U.S. forces of occupation in Germany to "…take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany", was thus replaced by JCS 1779 which instead stressed that "An orderly, prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany.” JCS 1067 had then been in effect for over two years. The restrictions placed on German heavy industry production were partly ameliorated, permitted steel production levels were raised from 25% of pre-war capacity to a new limit placed at 50% of pre-war capacity.

The dismantling of German industry continued, and in 1949 Konrad Adenauer wrote to the Allies requesting that it end, citing the inherent contradiction between encouraging industrial growth and removing factories and also the unpopularity of the policy. Support for dismantling was by this time coming predominantly from the French, and the Petersberg Agreement of November 1949 reduced the levels vastly, though dismantling of minor factories continued until 1951. The first "level of industry" plan, signed by the Allies in March 29, 1946, had stated that German heavy industry was to be lowered to 50% of its 1938 levels by the destruction of 1,500 listed manufacturing plants. In January 1946 the Allied Control Council set the foundation of the future German economy by putting a cap on German steel production—the maximum allowed was set at about 5,800,000 tons of steel a year, equivalent to 25% of the prewar production level. The UK, in whose occupation zone most of the steel production was located, had argued for a more limited capacity reduction by placing the production ceiling at 12 million tons of steel per year, but had to submit to the will of the U.S., France and the Soviet Union (which had argued for a 3 million ton limit). Steel plants thus made redundant were to be dismantled. Germany was to be reduced to the standard of life it had known at the height of the Great depression (1932). Car production was set to 10% of prewar levels, etc.

The first "German level of industry" plan was subsequently followed by a number of new ones, the last signed in 1949. By 1950, after the virtual completion of the by then much watered-out "level of industry" plans, equipment had been removed from 706 manufacturing plants in western Germany and steel production capacity had been reduced by 6,700,000 tons. Vladimir Petrov concludes that the Allies "delayed by several years the economic reconstruction of the wartorn continent, a reconstruction which subsequently cost the United States billions of dollars." In 1951 West Germany agreed to join the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) the following year. This meant that some of the economic restrictions on production capacity and on actual production that were imposed by the International Authority for the Ruhr were lifted, and that its role was taken over by the ECSC.

The only major power whose infrastructure had not been significantly harmed was the United States. It had entered the war later than most European countries, and had only suffered limited damage to its own territory. American gold reserves were still intact as was its massive agricultural and manufacturing base, the country enjoying a robust economy. The war years had seen the fastest period of economic growth in the nation's history, as American factories supported both its own war effort and that of its allies. After the war, these plants quickly retooled to produce consumer goods, and the scarcity of the war years was replaced by a boom in consumer spending. The long term health of the economy was dependent on trade, however, as continued prosperity would require markets to export these goods. Marshall Plan aid would largely be used by the Europeans to buy manufactured goods and raw materials from the United States.

Another strong motivating factor for the United States, and an important difference from the post World War I era, was the beginning of the Cold War. Some in the American government had grown deeply suspicious of Soviet actions. George Kennan, one of the leaders in developing the plan, was already predicting a bipolar division of the world. To him the Marshall Plan was the centerpiece of the new doctrine of containment. It should be noted that when the Marshall Plan was initiated, the wartime alliances were still somewhat intact and the Cold War had not yet truly begun, and for most of those who developed the Marshall Plan, fear of the Soviet Union was not the overriding concern it would be in later years.

Still, the power and popularity of indigenous communist parties in several Western European states worried the United States. In both France and Italy, the poverty of the postwar era had provided fuel for their communist parties, which had also played central roles in the resistance movements of the war. These parties had seen significant electoral success in the postwar elections, with the communists becoming the largest single party in France. Though today most historians feel the threat of France and Italy falling to the communists was remote, it was regarded as a very real possibility by American policy makers at the time. The American government of Harry Truman began to believe this possibility in 1946, notably with Churchill's Iron Curtain speech, given in Truman's presence. In their minds, The United States needed to adopt a definite position on the world scene or fear losing credibility. The emerging doctrine of containment argued that the United States needed to substantially aid non-communist countries to stop the spread of Soviet influence. There was also some hope that the Eastern European nations would join the plan, and thus be pulled out of the emerging Soviet bloc.

Even before the Marshall Plan, the United States was spending a great deal to help Europe recover. An estimated $9 billion was spent during the period from 1945 to 1947. Much of this aid was indirect, coming in the form of continued lend-lease agreements, and through the many efforts of American troops to restore infrastructure and help refugees. A number of bilateral aid agreements had been signed, perhaps the most important of which was the Truman Doctrine's pledge to provide military assistance to Greece and Turkey. The infant United Nations also launched a series of humanitarian and relief efforts almost wholly funded by the United States. These efforts had important effects, but they lacked any central organization and planning, and failed to meet many of Europe's more fundamental needs. Already in 1943, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was founded to provide relief to areas liberated from Axis powers after World War II. UNRRA provided billions of dollars of rehabilitation aid, and helped about 8 million refugees. It ceased operations in the DP camps of Europe in 1947, in anticipation of the American-directed Marshall Plan. Many of its functions were transferred to several UN agencies.

Early ideas

Long before Marshall's speech a number of figures had raised the notion of a reconstruction plan for Europe. U.S. Secretary of State James F. Byrnes presented an early version of the plan during a speech, " Restatement of Policy on Germany" held at the Stuttgart Opera House on September 6, 1946. In a series of reports called The President's Economic Mission to Germany and Austria, commissioned by Harry S. Truman, former President Herbert Hoover presented a very critical view of the result of current occupation policies in Germany. In the reports Hoover provided proposals for a fundamental change of occupation policy. In addition, General Lucius D. Clay asked industrialist Lewis H. Brown to inspect postwar Germany and draft " A Report on Germany" in 1947, containing basic facts relating to the problems in Germany with recommendations for reconstruction. Undersecretary of State Dean Acheson had made a major speech on the issue, which had mostly been ignored, and Vice President Alben W. Barkley had also raised the idea.

The main alternative to large quantities of American aid was to take it from Germany. In 1944 this notion became known as the Morgenthau plan, named after U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr. It advocated extracting massive war reparations from Germany to help rebuild those countries it had attacked, and also to prevent Germany from ever being rebuilt. Closely related was the Monnet plan of French bureaucrat Jean Monnet that proposed giving France control over the German coal areas of the Ruhr and Saar and using these resources to bring France to 150% of pre-war industrial production. In 1946 the occupying powers agreed to put strict limits on how quickly Germany could reindustrialize. Limits were placed on how much coal and steel could be produced. The first German industrial plan, also known as the "level of industry agreement", was signed in early 1946 and stated that German heavy industry was to be reduced to 50% of its 1938 levels by the destruction of 1,500 listed manufacturing plants The problems inherent in this plan became apparent by the end of 1946, and the agreement was revised several times, the last time in 1949. Dismantling of factories continued however into 1950. Germany had long been the industrial giant of Europe, and its poverty held back the general European recovery. The continued scarcity in Germany also led to considerable expenses for the occupying powers, which were obligated to try to make up the most important shortfalls. These factors, combined with widespread public condemnation of the plans after their leaking to the press, led to the de facto rejection of the Monnet and Morgenthau plans. Some of their ideas, however, did partly live on in Joint Chiefs of Staff Directive 1067, a plan which was effectively the basis for US Occupation policy until July 1947. The mineral-rich industrial centers Saar and Silesia were removed from Germany, a number of civilian industries were destroyed in order to limit production, and the Ruhr Area was in danger of being removed as late as 1947. By April of 1947, however, Truman, Marshall and Undersecretary of State Dean Acheson were convinced of the need for substantial quantities of aid from the United States.

The idea of a reconstruction plan was also an outgrowth of the ideological shift that had occurred in the United States in the Great Depression. The economic calamity of the 1930s had convinced many that the unfettered free market could not guarantee economic well-being. Many who had worked on designing the New Deal programs to revive the American economy now sought to apply these lessons to Europe. At the same time the Great Depression had shown the dangers of tariffs and protectionism, creating a strong belief in the need for free trade and European economic integration. Unhappy with the Morgenthau-plan consequences, in a March 18, 1947 report former U.S. President Herbert Hoover remarked: "There is the illusion that the New Germany left after the annexations can be reduced to a 'pastoral state'. It cannot be done unless we exterminate or move 25,000,000 people out of it." Policy changed swiftly in a few months after and reversed the Morgenthau policy.

The speech

The earlier public discussions of the need for reconstruction had largely been ignored, as it was not clear that it was establishing official administration policy. It was decided that all doubt must be removed by a major address by Secretary of State George Marshall. Marshall gave the address to the graduating class of Harvard University on June 5, 1947. Standing on the steps of Memorial Church in Harvard Yard, he offered American aid to promote European recovery and reconstruction. Marshall outlined the US government's preparedness to contribute to European recovery. "It is logical," said Marshall, "that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health to the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is not directed against any country, but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos. Any government that is willing to assist in recovery will find full co-operation on the part of the U.S.A." Marshall was convinced that economic stability would provide political stability in Europe. He offered aid, but the European countries had to organise the programme themselves.

The speech, written by Charles Bohlen, contained virtually no details and no numbers. The most important element of the speech was the call for the Europeans to meet and create their own plan for rebuilding Europe, and that the United States would then fund this plan. The administration felt that the plan would likely be unpopular among many Americans, and the speech was mainly directed at a European audience. In an attempt to keep the speech out of American papers journalists were not contacted, and on the same day Truman called a press conference to take away headlines. By contrast Acheson was dispatched to contact the European media, especially the British media, and the speech was read in its entirety on the BBC.

Rejection by the Soviets

British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin heard Marshall's radio broadcast speech and immediately contacted French Foreign Minister Georges Bidault to begin preparing a quick European response to (and acceptance of) the offer. The two agreed that it would be necessary to invite the Soviets as the other major allied power. Marshall's speech had explicitly included an invitation to the Soviets, feeling that excluding them would have been too clear a sign of distrust. State Department officials, however, knew that Stalin would almost certainly not participate, and that any plan that would send large amounts of aid to the Soviets was unlikely to be approved by Congress.

Stalin was at first interested in the plan. He felt that the Soviet Union stood in a good position after the war and would be able to dictate the terms of the aid. He thus dispatched foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov to Paris to meet with Bevin and Bidault. The British and French leadership shared the American lack of genuine interest in Soviet participation, and they presented Molotov with conditions that the Soviets could never accept. The most important condition was that every country to join the plan would need to have its economic situation independently assessed, scrutiny to which the Soviets could not agree. Bevin and Bidault also insisted that any aid be accompanied by the creation of a unified European economy, something incompatible with the strict Soviet command economy. Molotov left Paris, rejecting the plan.

On July 12, a larger meeting was convened in Paris. Every country of Europe was invited, with the exceptions of Spain (which had stayed out of World War II but had sympathized with the Axis powers) and the small states of Andorra, San Marino, Monaco, and Liechtenstein. The Soviet Union was invited with the understanding that it would refuse. The states of the future Eastern Bloc were also approached, and Czechoslovakia and Poland agreed to attend. In one of the clearest signs of Soviet control over the region, the Czechoslovakian foreign minister, Jan Masaryk, was summoned to Moscow and berated by Stalin for thinking of joining the Marshall Plan. Polish Prime minister Josef Cyrankiewicz was rewarded by Stalin for the Polish rejection of the Plan. Russia rewarded Poland with a huge 5 year trade agreement, 450 million in credit, 200,000 tons of grain, heavy machinery and factories. Stalin saw the Plan as a significant threat to Soviet control of Eastern Europe and believed that economic integration with the West would allow these countries to escape Soviet guidance. The Americans shared this view and hoped that economic aid could counter the growing Soviet influence. They were not too surprised, therefore, when the Czechoslovakian and Polish delegations were prevented from attending the Paris meeting. The other Eastern European states immediately rejected the offer. Finland also declined in order to avoid antagonizing the Soviets. The Soviet Union's "alternative" to the Marshall plan, which was purported to involve Soviet subsidies and trade with western Europe, became known as the Molotov Plan, and later, the COMECON. In a 1947 speech to the United Nations, Soviet deputy foreign minister Andrei Vyshinsky said that the Marshall Plan violated the principles of the United Nations. He accused the United States of attempting to impose its will on other independent states, while at the same time using economic resources distributed as relief to needy nations as an instrument of political pressure.

Negotiations

Turning the plan into reality required negotiations both among the participating nations, and also to get the plan through the United States Congress. Thus sixteen nations met in Paris to determine what form the American aid would take, and how it would be divided. The negotiations were long and complex, with each nation having its own interests. France's major concern was that Germany not be rebuilt to its previous threatening power. The Benelux countries, despite also suffering under the Nazis, had long been closely linked to the German economy and felt their prosperity depended on its revival. The Scandinavian nations, especially Sweden, insisted that their long-standing trading relationships with the Eastern Bloc nations not be disrupted and that their neutrality not be infringed. Britain insisted on special status, concerned that if it were treated equally with the devastated continental powers it would receive virtually no aid. The Americans were pushing the importance of free trade and European unity to form a bulwark against communism. The Truman administration, represented by William Clayton, promised the Europeans that they would be free to structure the plan themselves, but the administration also reminded the Europeans that for the plan to be implemented, it would have to pass Congress. The majority of Congress was committed to free trade and European integration, and also were hesitant to spend too much of the money on Germany.

Agreement was eventually reached and the Europeans sent a reconstruction plan to Washington. In this document the Europeans asked for $22 billion in aid. Truman cut this to $17 billion in the bill he put to Congress. The plan met sharp opposition in Congress, mostly from the portion of the Republican Party that advocated a more isolationist policy and was weary of massive government spending. This group's most prominent representative was Robert A. Taft. The plan also had opponents on the left, with Henry A. Wallace a strong opponent. Wallace saw the plan as a subsidy for American exporters and sure to polarize the world between East and West. This opposition was greatly reduced by the shock of the overthrow of the democratic government of Czechoslovakia in February 1948. Soon after a bill granting an initial $5 billion passed Congress with strong bipartisan support. The Congress would eventually donate $12.4 billion in aid over the four years of the plan.

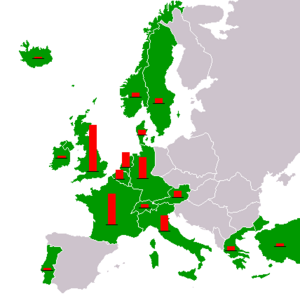

Truman signed the Marshall Plan into law on April 3, 1948, establishing the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA) to administer the program. ECA was headed by economic cooperation administrator Paul G. Hoffman. In the same year, the participating countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, West Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States) signed an accord establishing a master financial-aid-coordinating agency, the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (later called the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, OECD), which was headed by Frenchman Robert Marjolin.

Implementation

The first substantial aid went to Greece and Turkey in January 1947, which were seen as being on the front lines of the battle against communist expansion and were already being aided under the Truman Doctrine. Initially the UK had supported the anti-communist factions in those countries, but due to its dire economic condition it requested the U.S. to continue its efforts. The ECA formally began operation in July 1948. Its official mission statement was to give a boost to the European economy: to promote European production, to bolster European currency, and to facilitate international trade, especially with the United States, whose economic interest required Europe to become wealthy enough to import U.S. goods. Another unofficial goal of ECA (and of the Marshall Plan) was the containment of growing Soviet influence in Europe, evident especially in the growing strength of communist parties in Czechoslovakia, France, and Italy.

The Marshall Plan money was transferred to the governments of the European nations. The funds were jointly administered by the local governments and the ECA. Each European capital had an ECA envoy, generally a prominent American businessman, who would advise on the process. The cooperative allocation of funds was encouraged, and panels of government, business, and labor leaders were convened to examine the economy and see where aid was needed.

The Marshall Plan aid was mostly used for the purchase of goods from the United States. The European nations had all but exhausted their foreign exchange reserves during the war, and the Marshall Plan aid represented almost their sole means of importing goods from abroad. At the start of the plan these imports were mainly much-needed staples such as food and fuel, but later the purchases turned towards reconstruction needs as was originally intended. In the latter years, under pressure from the United States Congress and with the outbreak of the Korean War, an increasing amount of the aid was spent on rebuilding the militaries of Western Europe. Of the some $13 billion allotted by mid-1951, $3.4 billion had been spent on imports of raw materials and semi-manufactured products; $3.2 billion on food, feed, and fertilizer; $1.9 billion on machines, vehicles, and equipment; and $1.6 billion on fuel.

Also established were counterpart funds, which used Marshall Plan aid to establish funds in the local currency. According to ECA rules 60% of these funds had to be invested in industry. This was prominent in Germany, where these government-administered funds played a crucial role lending money to private enterprises which would spend the money rebuilding. These funds played a central role in the reindustrialization of Germany. In 1949 – 50, for instance, 40% of the investment in the German coal industry was by these funds. The companies were obligated to repay the loans to the government, and the money would then be lent out to another group of businesses. This process has continued to this day in the guise of the state owned KfW bank. The Special Fund, then supervised by the Federal Economics Ministry, was worth over DM 10 billion in 1971. In 1997 it was worth DM 23 billion. Through the revolving loan system, the Fund had by the end of 1995 made low-interest loans to German citizens amounting to around DM 140 billion. The other 40% of the counterpart funds were used to pay down the debt, stabilize the currency, or invest in non-industrial projects. France made the most extensive use of counterpart funds, using them to reduce the budget deficit. In France, and most other countries, the counterpart fund money was absorbed into general government revenues, and not recycled as in Germany.

A far less expensive, but also quite effective, ECA initiative was the Technical Assistance Program. This program funded groups of European engineers and industrialists to visit the United States and tour mines, factories, and smelters so that they could then copy the American advances at home. At the same time several hundred American technical advisors were sent to Europe.

Expenditures

The Marshall Plan aid was divided amongst the participant states on a roughly per capita basis. A larger amount was given to the major industrial powers, as the prevailing opinion was that their resuscitation was essential for general European revival. Somewhat more aid per capita was also directed towards the Allied nations, with less for those that had been part of the Axis or remained neutral. The table below shows Marshall Plan aid by country and year (in millions of dollars) from The Marshall Plan Fifty Years Later. There is no clear consensus on exact amounts, as different scholars differ on exactly what elements of American aid during this period was part of the Marshall Plan.

| Country | 1948/49 ($ millions) |

1949/50 ($ millions) |

1950/51 ($ millions) |

Cumulative ($ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 232 | 166 | 70 | 468 | |

| 195 | 222 | 360 | 777 | |

| 103 | 87 | 195 | 385 | |

| 1085 | 691 | 520 | 2296 | |

| 510 | 438 | 500 | 1448 | |

| 175 | 156 | 45 | 366 | |

| 6 | 22 | 15 | 43 | |

| 88 | 45 | 0 | 133 | |

| 594 | 405 | 205 | 1204 | |

| 471 | 302 | 355 | 1128 | |

| 82 | 90 | 200 | 372 | |

| 0 | 0 | 70 | 70 | |

| 39 | 48 | 260 | 347 | |

| 0 | 0 | 250 | 250 | |

| 28 | 59 | 50 | 137 | |

| 1316 | 921 | 1060 | 3297 | |

| Totals | 4,924 | 3,652 | 4,155 | 12,721 |

Effects

The Marshall Plan ended in 1953, as originally scheduled. Any effort to extend it was halted by the growing cost of the Korean War and rearmament. U.S. Republicans hostile to the plan had also gained seats in the 1950 Congressional elections, and conservative opposition to the plan was revived. Thus the plan ended in 1951, though various other forms of American aid to Europe continued afterwards.

The years 1948 to 1952 saw the fastest period of growth in European history. Industrial production increased by 35%. Agricultural production substantially surpassed pre-war levels. The poverty and starvation of the immediate postwar years disappeared, and Western Europe embarked upon an unprecedented two decades of growth that saw standards of living increase dramatically. There is some debate among historians over how much this should be credited to the Marshall Plan. Most reject the idea that it alone miraculously revived Europe, as evidence shows that a general recovery was already underway. Most believe that the Marshall Plan sped this recovery, but did not initiate it.

The political effects of the Marshall Plan may have been just as important as the economic ones. Marshall Plan aid allowed the nations of Western Europe to relax austerity measures and rationing, reducing discontent and bringing political stability. The communist influence on Western Europe was greatly reduced, and throughout the region communist parties faded in popularity in the years after the Marshall Plan. The trade relations fostered by the Marshall Plan helped forge the North Atlantic alliance that would persist throughout the Cold War. At the same time the nonparticipation of the states of Eastern Europe was one of the first clear signs that the continent was now divided.

The Marshall Plan also played an important role in European integration. Both the Americans and many of the European leaders felt that European integration was necessary to secure the peace and prosperity of Europe, and thus used Marshall Plan guidelines to foster integration. In some ways this effort failed, as the OEEC never grew to be more than an agent of economic cooperation. Rather it was the separate European Coal and Steel Community, which notably excluded Britain, that would eventually grow into the European Union. However, the OEEC served as both a testing and training ground for the structures and bureaucrats that would later be used by the European Economic Community. The Marshall Plan, linked into the Bretton Woods system, also mandated free trade throughout the region.

While some modern historians today feel some of the praise for the Marshall Plan is exaggerated, it is still viewed favorably and many thus feel that a similar project would help other areas of the world. After the fall of communism several proposed a "Marshall Plan for Eastern Europe" that would help revive that region. Others have proposed a Marshall Plan for Africa to help that continent, and U.S. vice president Al Gore suggested a Global Marshall Plan. "Marshall Plan" has become a metaphor for any very large scale government program that is designed to solve a specific social problem. It is usually used when calling for federal spending to correct a perceived failure of the private sector.

The West German economic recovery was partly due to the economic aid provided by the Marshall Plan, but mainly it was due to the currency reform of 1948 which replaced the Reichsmark with the Deutsche Mark as legal tender, halting rampant inflation. This act to strengthen the German economy had been explicitly forbidden during the two years that the occupation directive JCS 1067 was in effect. The Allied dismantling of the West German coal and steel industry finally ended in 1951. The Marshall Plan was only one of several forces behind the German recovery. Even so, in Germany the myth of the Marshall Plan is still alive. According to Marshall Plan 1947–1997 A German View by Susan Stern, many Germans still believe that Germany was the exclusive beneficiary of the plan, that it consisted of a free gift of vast sums of money, and that it was solely responsible for the German economic recovery in the 1950s.

Repayment

The Organization for European Economic Cooperation took the leading role in allocating funds, and the ECA arranged for the transfer of the goods. The American supplier was paid in dollars, which were credited against the appropriate European Recovery Program funds. The European recipient, however, was not given the goods as a gift, but had to pay for them (though not necessarily at once, on credit etc.) in local currency, which was then deposited by the government in a counterpart fund. This money, in turn, could be used by the ERP countries for further investment projects.

Most of the participating ERP governments were aware from the beginning that they would never have to return the counterpart fund money to the U.S.; it was eventually absorbed into their national budgets and "disappeared." Originally the total American aid to Germany (in contrast to grants given to other countries in Europe) had to be repaid. But under the London debts agreement of 1953, the repayable amount was reduced to about $1 billion. Aid granted after 1 July 1951 amounted to around $270 million, of which Germany had to repay $16.9 million to the Washington Export-Import Bank. In reality, Germany did not know until 1953 exactly how much money it would have to pay back to the U.S., and insisted that money was given out only in the form of interest-bearing loans — a revolving system ensuring the funds would grow rather than shrink. A lending bank was charged with overseeing the program. European Recovery Program loans were mostly used to support small- and medium-sized businesses. Germany paid the U.S. back in installments (the last check was handed over in June 1971). However, the money was not paid from the ERP fund, but from the central government budget.

Areas without the Marshall Plan

Large parts of the world devastated by World War II did not benefit from the Marshall Plan. The only major Western European nation excluded was Francisco Franco's Spain. After the war, it pursued a policy of self-sufficiency, currency controls, and quotas, with little success. With the escalation of the Cold War, the United States reconsidered its position, and in 1951 embraced Spain as an ally, encouraged by Franco's aggressive anti-communist policies. Over the next decade, a considerable amount of American aid would go to Spain, but less than its neighbors had received under the Marshall Plan.

While the western portion of the Soviet Union had been as badly affected as any part of the world by the war, the eastern portion of the country was largely untouched and had seen a rapid industrialization during the war. The Soviets also imposed large reparations payments on the Axis allies that were in its sphere of influence. Finland, Hungary, Romania, and especially East Germany were forced to pay vast sums and ship large amounts of supplies to the USSR. These reparation payments meant that the Soviet Union received almost as much as any of the countries receiving Marshall Plan aid.

Eastern Europe saw no Marshall Plan money, as their governments rejected joining the program, and moreover received little help from the Soviets. The Soviets did establish COMECON as a rebuttal to the Marshall Plan. The members of Comecon looked to the Soviet Union for oil; in turn, they provided machinery, equipment, agricultural goods, industrial goods, and consumer goods to the Soviet Union. Economic recovery in the east was much slower than in the west, and the economies never fully recovered in the communist period, resulting in the formation of the shortage economies and a gap in wealth between East and West. Finland, which did not join the Marshall Plan and which was required to give large reparations to the USSR, saw its economy recover to pre-war levels in 1947. France, which received billions of dollars through the Marshall Plan, similarly saw its economy return to pre-war levels in 1947. By mid-1948 industrial production in Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia had recovered to a level somewhat above pre-war level.

Japan too, had been badly damaged by the war. However, the American people and Congress were far less sympathetic towards the Japanese than they were to the Europeans. Japan was also not considered to have as great a strategic or economic importance to the United States. Thus no grand reconstruction plan was ever created, and the Japanese economic recovery before 1950 was slow. However, by 1952 growth had picked up, such that Japan continued, from 1952 to 1971 to grow in real GNP at an average annual rate of 9.6 percent. The US by contrast, grew at a rate of 2.9 percent from 1952 to 1991. The Korean War may have played a role in the early economic growth in Japan. It began in 1950 and Japan became the main staging ground for the United Nations war effort, and a crucial supplier of material. One well known example is that of the Toyota company. In June 1950, the company produced 300 trucks, and was on the verge of going out of business. The first months of the war saw the military order over 5,000 vehicles, and the company was revived. During the four years of the Korean War, the Japanese economy saw a substantially larger infusion of cash than had any of the Marshall Plan nations.

Canada, like the United States, was little damaged by the war and in 1945 was one of the world's largest economies. The Canadian economy had long been more dependent than the American one on trade with Europe, and after the war there were signs that the Canadian economy was struggling. In April 1948, the U.S. Congress passed the provision in the plan that allowed the aid to be used in purchasing goods from Canada. The new provision ensured the health of that nation's economy as Canada made over a billion dollars in the first two years of operation. This contrasted heavily with the treatment Argentina, another major economy dependent on its agricultural exports with Europe, received from the ECA, as the country was deliberately excluded from participation in the Plan due to political differences between the U.S. and then-president Perón. This would damage the Argentine agricultural sector and help to precipitate an economic crisis in the country.

Criticism

Early criticism

Initial criticism of the Marshall Plan came from a number of liberal economists. Wilhelm Röpke, who influenced German chancellor Ludwig Erhard in his economic recovery program, believed recovery would be found in eliminating central planning and restoring a market economy in Europe, especially in those countries which had adopted more fascist and corporatist economic policies. Röpke criticized the Marshall plan for forestalling the transition to the free market by subsidizing the current, failing systems. Erhard put Röpke's theory into practice and would later credit Röpke's influence for the West Germany's preeminent success. Henry Hazlitt criticized the Marshall Plan in his 1947 book Will Dollars Save the World?, arguing that economic recovery comes through savings, capital accumulation and private enterprise, and not through large cash subsidies. Ludwig von Mises also criticized the Marshall Plan in 1951, believing that "The American subsidies make it possible for [Europe's] governments to conceal partially the disastrous effects of the various socialist measures they have adopted." He also made a general critique of foreign aid, believing it creates ideological enemies rather than economic partners by stifling the free market.

Modern criticism

Criticism of the Marshall Plan became prominent among historians of the revisionist school, such as Walter LaFeber, during the 1960s and 1970s. They argued that the plan was American economic imperialism, and that it was an attempt to gain control over Western Europe just as the Soviets controlled Eastern Europe. In a review of West Germany's economy from 1945 to 1951, German analyst Werner Abelshauser concluded that "foreign aid was not crucial in starting the recovery or in keeping it going." The economic recoveries of France, Italy, and Belgium, Cowen found, also predated the flow of U.S. aid. Belgium, the country that relied earliest and most heavily on free market economic policies after its liberation in 1944, experienced the fastest recovery and avoided the severe housing and food shortages seen in the rest of continental Europe.

Former U.S. Chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank Alan Greenspan gives most credit to Ludwig Erhard for Europe's economic recovery. Greenspan writes in his memoir The Age of Turbulence that Erhard's economic policies were the most important aspect of postwar Western Europe recovery, far outweighing the contributions of the Marshall Plan. He states that it was Erhard's reductions in economic regulations that permitted Germany's miraculous recovery, and that these policies also contributed to the recoveries of many other European countries. Japan's recovery is also used as a counter-example, since it experienced rapid growth without any aid whatsoever. Its recovery is attributed to traditional economic stimuli, such as increases in investment, fueled by a high savings rate and low taxes. Japan saw a large infusion of cash during the Korean war, but because this came in the form of investment and not subsidies, it proved far more beneficial.

Criticism of the Marshall Plan also aims at showing that it has begun a legacy of disastrous foreign aid programs. Since the 1990s, economic scholarship has been more hostile to the idea of foreign aid. For example, Alberto Alesina and Beatrice Weder, summing up economic literature on foreign aid and corruption, find that aid is primarily used wastefully and self-servingly by government officials, and ends up increasing governmental corruption. This policy of promoting corrupt government is then attributed back to the initial impetus of the Marshall Plan.

Noam Chomsky wrote that the amount of American dollars given to France and the Netherlands equaled the funds these countries used to finance their military forces in southeast Asia. The Marshall Plan was said to have "set the stage for large amounts of private U.S. investment in Europe, establishing the basis for modern transnational corporations." Other criticism of the Marshall Plan stemmed from reports that the Netherlands used a significant portion of the aid it received to try to re-conquer Indonesia in the Indonesian War of Independence.

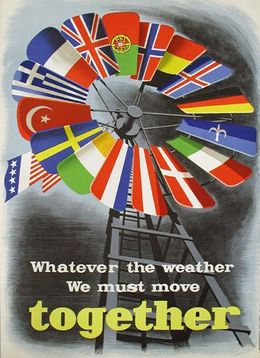

The E.R.P. in numismatics

The E.R.P. has left such a legacy behind that has been the main motive of many collectors and bullion coins. One of the most recent is the 20 euro Post War Period coin, minted in September 17, 2003. The reverse side of the coin is based on the design of two famous posters of the era: the “Four in a Jeep” and the E.R.P. The German inscription “Wiederaufbau in Österreich” translates as “Reconstruction in Austria”, one of the countries aided by this program.