Romanticism

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: British History 1750-1900

- Romantics redirects here, for the band, see The Romantics

Romanticism is an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that originated in 18th century Western Europe during the industrial revolution. In part a revolt against aristocratic, social, and political norms of the Enlightenment period and a reaction against the rationalization of nature, in art and literature. It stressed strong emotion as a source of aesthetic experience, placing new emphasis on such emotions as trepidation, horror, and the awe experienced in confronting the sublimity of nature. It elevated folk art, nature and custom, as well as arguing for an epistemology based on nature, which included human activity conditioned by nature in the form of language, custom and usage. It was influenced by ideas of the Enlightenment and elevated medievalism and elements of art and narrative perceived to be from the medieval period. The name "romantic" itself comes from the term " romance" which is a prose or poetic heroic narrative originating in medieval literature and romantic literature.

The ideologies and events of the French Revolution and Industrial Revolution are thought to have influenced the movement. Romanticism elevated the achievements of what it perceived as misunderstood heroic individuals and artists that altered society. It also legitimized the individual imagination as a critical authority which permitted freedom from classical notions of form in art. There was a strong recourse to historical and natural inevitability in the representation of its ideas.

Characteristics

In a general sense, Romanticism refers to several groups of artists, poets, writers, and musicians as well as political, philosophical and social thinkers and trends of the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Europe. But a precise characterization and a specific description of Romanticism have been objects of intellectual history and literary history for all of the twentieth century without any great measure of consensus emerging. Arthur Lovejoy attempted to demonstrate the difficulty of this problem in his seminal article "On The Discrimination of Romanticisms" in his Essays in the History of Ideas (1948); some scholars see romanticism as completely continuous with the present, some see it as the inaugural moment of modernity, some see it as the beginning of a tradition of resistance to the Enlightenment, and still others date it firmly in the direct aftermath of the French Revolution. Another definition comes from Charles Baudelaire: "Romanticism is precisely situated neither in choice of subject nor exact truth, but in a way of feeling."

Many intellectual historians have seen Romanticism as a key moment in the Counter-Enlightenment, a reaction against the Age of Enlightenment. Whereas the thinkers of the Enlightenment emphasized the primacy of deductive reason, Romanticism emphasized intuition, imagination, and feeling, to a point that has led to some Romantic thinkers being accused of irrationalism.

Music

Romanticism and music

- In general, the term "Romanticism" when applied to music has come to mean the period roughly from the 1820s until 1910. The contemporary application of 'romantic' to music did not coincide with modern categories: in 1810 E.T.A. Hoffmann called Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven the three "Romantic Composers", and Ludwig Spohr used the term "good Romantic style" to apply to parts of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. Technically, Mozart is considered classical and by most standards, Beethoven is the start of the musical Romantic period. By the early 20th century, the sense that there had been a decisive break with the musical past led to the establishment of the 19th century as " The Romantic Era," and as such it is referred to in the standard encyclopedias of music.

The traditional modern discussion of the music of Romanticism includes elements, such as the growing use of folk music, which are also directly related to the broader current of Romantic nationalism in the arts (for a detailed discussion of its musical manifestations, see musical nationalism).

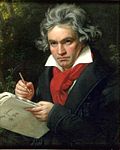

Some aspects of Romanticism are already present in eighteenth-century music. The heightened contrasts and emotions of Sturm und Drang [German for "Storm and Stress"] seem a precursor of the Gothic in literature, or the sanguinary elements of some of the operas of the period of the French Revolution. The libretti of Lorenzo da Ponte for Mozart, and the eloquent music the latter wrote for them, convey a new sense of individuality and freedom. In Beethoven, the Romantic generation's ideal of the artist as hero, the concept of the Romantic musician begins to reveal itself— the man who morally challenged the Emperor Napoleon himself by striking him out from the dedication of the Eroica Symphony. In Beethoven's Fidelio he creates the apotheosis of the 'rescue operas' which were another feature of French musical culture during the revolutionary period, in order to hymn the freedom which underlay the thinking of all radical artists in the years of hope after the Congress of Vienna.

Of the contemporary music culture, the romantic musician followed a public career, depending on sensitive middle-class audiences rather than on a courtly patron. Public persona characterized a new generation of virtuosi who made their way as soloists, epitomized in the careers of Paganini and Liszt.

Beethoven's use of tonal architecture in such a way as to allow significant expansion of musical forms and structures was immediately recognized as bringing a new dimension to music. The later piano music and string quartets, especially, showed the way to a completely unexplored musical universe. The writer, critic (and composer) Hoffmann was able to write of the supremacy of instrumental music over vocal music in expressiveness, a concept which would previously have been regarded as absurd. Hoffmann himself, as a practitioner both of music and literature, encouraged the notion of music as 'programmatic' or telling a story, an idea which new audiences found attractive, however irritating it was to some composers (e.g. Felix Mendelssohn). New developments in instrumental technology in the early nineteenth century—iron frames for pianos, wound metal strings for string instruments—enabled louder dynamics, more varied tone colours, and the potential for sensational virtuosity. Such developments swelled the length of pieces, introduced programmatic titles, and created new genres such as the free standing overture or tone-poem, the piano fantasy, nocturne and rhapsody, and the virtuoso concerto, which became central to musical romanticism.

In opera, a new Romantic atmosphere combining supernatural terror and melodramatic plot in a folkloric context was most successfully achieved by Weber's Der Freischütz (1817, 1821). Enriched timbre and colour marked the early orchestration of Hector Berlioz in France, and the grand operas of Meyerbeer. Amongst the radical fringe of what became mockingly characterised (adopting Wagner's own words) as 'artists of the future', Liszt and Wagner each embodied the Romantic cult of the free, inspired, charismatic, perhaps ruthlessly unconventional individual artistic personality.

It is the period of 1815 to 1848 which must be regarded as the true age of Romanticism in music - the age of the last compositions of Beethoven (d. 1827) and Schubert (d. 1828), of the works of Schumann (d. 1856) and Chopin (d.1849), of the early struggles of Berlioz and Richard Wagner, of the great virtuosi such as Paganini (d. 1840), and the young Liszt and Thalberg. Now that we are able to listen to the work of Mendelssohn (d. 1847) stripped of the Biedermeier reputation unfairly attached to it, he can also be placed in this more appropriate context. After this period, with Chopin and Paganini dead, Liszt retired from the concert platform at a minor German court, Wagner effectively in exile until he obtained royal patronage in Bavaria, and Berlioz still struggling with the bourgeois liberalism which all but smothered radical artistic endeavour in Europe, Romanticism in music was surely past its prime—giving way, rather, to the period of musical romantics.

Visual art and literature

In visual art and literature, "Romanticism" typically refers to the late 18th century and the 19th century. Recurring themes found in Romantic literature are the criticism of the past, emphasis on women and children, and respect for nature. Furthermore, several romantic authors, such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, based their writings on the supernatural/ occult and human psychology, which they were fascinated with.

The Scottish poet James Macpherson influenced the early development of Romanticism with the international success of his Ossian cycle of poems published in 1762, inspiring both Goethe and the young Walter Scott.

An early German influence came from Johann Wolfgang Goethe whose 1774 novel The Sorrows of Young Werther had young men throughout Europe emulating its protagonist, a young artist with a very sensitive and passionate temperament. At that time Germany was a multitude of small separate states, and Goethe's works would have a seminal influence in developing a unifying sense of nationalism. Important writers of early German romanticism were Ludwig Tieck, Novalis ( Heinrich von Ofterdingen, 1799) and Friedrich Hoelderlin. Heidelberg later became a centre of German romanticism, where writers and poets such as Clemens Brentano, Achim von Arnim and Joseph von Eichendorff met regularly in literary circles. Romanticists often focused on emotions and dreams in their works. Other important motifs in German Romanticism are travelling, nature and ancient myths. The late German Romanticism (of, for example, E.T.A. Hoffmann's Der Sandmann - The Sandman, 1817, and Eichendorff's Das Marmorbild - The Marble Statue, 1819) was somewhat darker in its motifs and has some gothic elements.

Romanticism in British literature developed in a different form slightly later, mostly associated with the poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whose co-authored book " Lyrical Ballads" (1798) sought to reject Augustan poetry in favour of more direct speech derived from folk traditions. Both poets were also involved in Utopian social thought in the wake of the French Revolution. The poet and painter William Blake is the most extreme example of the Romantic sensibility in Britain, epitomised by his claim “I must create a system or be enslaved by another man's”. Blake's artistic work is also strongly influenced by Medieval illuminated books. The painters J.M.W. Turner and John Constable are also generally associated with Romanticism. Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley and John Keats constitute another phase of Romanticism in Britain. The historian Thomas Carlyle and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood represent the last phase of transformation into Victorian culture. William Butler Yeats, born in 1865, referred to his generation as "the last romantics."

In predominantly Roman Catholic countries Romanticism was less pronounced than in Germany and Britain, and tended to develop later, after the rise of Napoleon. François-René de Chateaubriand is often called the "Father of French Romanticism". In France, the movement is associated with the 19th century, particularly in the paintings of Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix, the plays, poems and novels of Victor Hugo (such as Les Misérables and Ninety-Three), and the novels of Stendhal. The composer Hector Berlioz is also important.

Inside Russia, the principal exponent of Romanticism is Alexander Pushkin. Mikhail Lermontov attempted to analyse and bring to light the deepest reasons for the Romantic idea of metaphysical discontent with society and self, and was much influenced by Lord Byron. The poet Fyodor Tyutchev was also an important figure of the movement in Russia, and was heavily influenced by the German Romantics.

Romanticism played an essential role in the national awakening of many Central European peoples lacking their own national states, particularly in Poland, which had recently lost its independence to Russia when its army crushed the Polish Rebellion under the reactionary Nicholas I. Revival of ancient myths, customs and traditions by Romanticist poets and painters helped to distinguish their indigenous cultures from those of the dominant nations (Russians, Germans, Austrians, Turks, etc.). Patriotism, nationalism, revolution and armed struggle for independence also became popular themes in the arts of this period. Arguably, the most distinguished Romanticist poet of this part of Europe was Adam Mickiewicz, who developed an idea that Poland was the Messiah of Nations, predestined to suffer just as Jesus had suffered to save all the people.

In the United States, the romantic gothic makes an early appearance with Washington Irving's Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1819), followed from 1823 onwards by the fresh Leatherstocking tales of James Fenimore Cooper, with their emphasis on heroic simplicity and their fervent landscape descriptions of an already-exotic mythicized frontier peopled by " noble savages", similar to the philosophical theory of Rousseau, like Uncas, " The Last of the Mohicans". There are picturesque elements in Washington Irving's essays and travel books. Edgar Allan Poe's tales of the macabre and his balladic poetry were more influential in France than at home, but the romantic American novel is fully developed in Nathaniel Hawthorne's atmosphere and melodrama. Later Transcendentalist writers such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson still show elements of its influence, as does the romantic realism of Walt Whitman. But by the 1880s, psychological and social realism was competing with romanticism. The poetry which Americans wrote and read was all romantic until the 1920s: Poe and Hawthorne, as well as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The poetry of Emily Dickinson – nearly unread in her own time – and Herman Melville's novel Moby-Dick can be taken as the epitomes of American Romantic literature, or as successors to it. As elsewhere (England, Germany, France), literary Romanticism had its counterpart in the visual arts, most especially in the exaltation of untamed America found in the paintings of the Hudson River School.

Nationalism

One of Romanticism's key ideas and most enduring legacies is the assertion of nationalism, which became a central theme of Romantic art and political philosophy. From the earliest parts of the movement, with their focus on development of national languages and folklore, and the importance of local customs and traditions, to the movements which would redraw the map of Europe and lead to calls for self-determination of nationalities, nationalism was one of the key vehicles of Romanticism, its role, expression and meaning.

Early Romantic nationalism was strongly inspired by Rousseau, and by the ideas of Johann Gottfried von Herder, who in 1784 argued that the geography formed the natural economy of a people, and shaped their customs and society.

The nature of nationalism changed dramatically, however, after the French Revolution with the rise of Napoleon, and the reactions in other nations. Napoleonic nationalism and republicanism were, at first, inspirational to movements in other nations: self-determination and a consciousness of national unity were held to be two of the reasons why France was able to defeat other countries in battle. But as the French Republic became Napoleon's Empire, Napoleon became not the inspiration for nationalism, but the object of its struggle. In Prussia, the development of spiritual renewal as a means to engage in the struggle against Napoleon was argued by, among others, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, a disciple of Kant. The word Volkstum, or nationality, was coined in German as part of this resistance to the now conquering emperor. Fichte expressed the unity of language and nation in his address "To the German Nation" in 1806:

- Those who speak the same language are joined to each other by a multitude of invisible bonds by nature herself, long before any human art begins; they understand each other and have the power of continuing to make themselves understood more and more clearly; they belong together and are by nature one and an inseparable whole. ...Only when each people, left to itself, develops and forms itself in accordance with its own peculiar quality, and only when in every people each individual develops himself in accordance with that common quality, as well as in accordance with his own peculiar quality—then, and then only, does the manifestation of divinity appear in its true mirror as it ought to be.

This view of nationalism inspired the collection of folklore by such people as the Brothers Grimm, the revival of old epics as national, and the construction of new epics as if they were old, as in the Kalevala, compiled from Finnish tales and folklore, or Ossian, where the claimed ancient roots were invented. The view that fairy tales, unless contaminated from outside, literary sources, were preserved in the same form over thousands of years, was not exclusive to Romantic Nationalists, but fit in well with their views that such tales expressed the primordial nature of a people. For instance, the Brothers Grimm rejected many tales they collected because of their similarity to tales by Charles Perrault, which they thought proved they were not truly German tales; Sleeping Beauty survived in their collection because the tale of Brynhildr convinced them that the figure of the sleeping princess was authentically German.