Electric field

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Electricity and Electronics

| Electromagnetism | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Electricity · Magnetism

|

||||||||||||

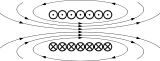

In physics, the space surrounding an electric charge has a property called an electric field. This electric field exerts a force on other charged objects. The concept of electric field was introduced by Michael Faraday.

The electric field is a vector with SI units of newtons per coulomb (N C-1) or, equivalently, volts per meter (V m-1). The direction of the field at a point is defined by the direction of the electric force exerted on a positive test charge placed at that point. The strength of the field is defined by the ratio of the electric force on a charge at a point to the magnitude of the charge placed at that point. Electric fields contain electrical energy with energy density proportional to the square of the field intensity. The electric field is to charge as acceleration is to mass and force density is to volume.

A moving charge has not just an electric field but also a magnetic field, and in general the electric and magnetic fields are not completely separate phenomena; what one observer perceives as an electric field, another observer in a different frame of reference perceives as a mixture of electric and magnetic fields. For this reason, one speaks of "electromagnetism" or "electromagnetic fields." In quantum mechanics, disturbances in the electromagnetic fields are called photons, and the energy of photons is quantized.

Definition (for electrostatics)

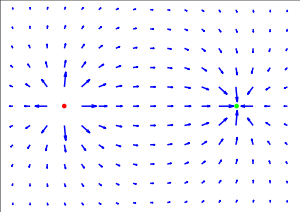

Electric field is defined as the electric force per unit charge. The direction of the field is taken to be the direction of the force it would exert on a positive test charge. The electric field is radially outward from a positive charge and radially in toward a negative point charge.

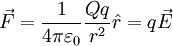

The electric field is defined as the proportionality constant between charge and force (in other words, the force per unit of test charge):

where

is the electric force given by Coulomb's law,

is the electric force given by Coulomb's law,- q is the charge of a "test charge",

However, note that this equation is only true in the case of electrostatics, that is to say, when there is nothing moving. The more general case of moving charges causes this equation to become the Lorentz force equation.

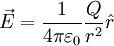

Coulomb's law

The electric field surrounding a point charge is given by Coulomb's law:

where

- Q is the charge of the particle creating the electric field,

- r is the distance from the particle with charge Q to the E-field evaluation point,

is the Unit vector pointing from the particle with charge Q to the E-field evaluation point,

is the Unit vector pointing from the particle with charge Q to the E-field evaluation point, is the Permittivity of free space.

is the Permittivity of free space. - r is the distance from the particle with charge Q to the E-field evaluation point,

Coulomb's law is actually a special case of Gauss's Law, a more fundamental description of the relationship between the distribution of electric charge in space and the resulting electric field. Gauss's law is one of Maxwell's equations, a set of four laws governing electromagnetics.

Properties (in electrostatics)

According to Equation (1) above, electric field is dependent on position. The electric field due to any single charge falls off as the square of the distance from that charge.

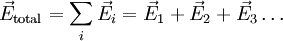

Electric fields follow the superposition principle. If more than one charge is present, the total electric field at any point is equal to the vector sum of the respective electric fields that each object would create in the absence of the others.

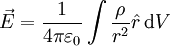

If this principle is extended to an infinite number of infinitesimally small elements of charge, the following formula results:

where

- ρ is the charge density, or the amount of charge per unit volume.

The electric field at a point is equal to the negative gradient of the electric potential there. In symbols,

where

- φ(x,y,z) is the scalar field representing the electric potential at a given point.

If several spatially distributed charges generate such an electric potential, e.g. in a solid, an electric field gradient may also be defined.

Considering the permittivity  of a material, which may differ from the permittivity of free space

of a material, which may differ from the permittivity of free space  , the electric displacement field is:

, the electric displacement field is:

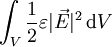

Energy in the electric field

The electric field stores energy. The energy density of the electric field is given by

where

is the permittivity of the medium in which the field exists

is the permittivity of the medium in which the field exists is the electric field vector.

is the electric field vector.

The total energy stored in the electric field in a given volume V is therefore

where

- dV is the differential volume element.

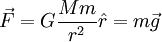

Parallels between electrostatics and gravity

Coulomb's law, which describes the interaction of electric charges:

is similar to the Newtonian gravitation law:

This suggests similarities between the electric field E and the gravitational field g, so sometimes mass is called "gravitational charge".

Similarities between electrostatic and gravitational forces:

- Both act in a vacuum.

- Both are central and conservative.

- Both obey an inverse-square law (both are inversely proprotional to square of r).

- Both propagate with finite speed c.

Differences between electrostatic and gravitational forces:

- Electrostatic forces are much greater than gravitational forces (by about 1036 times).

- Gravitational forces are always attractive in nature, whereas electrostatic forces may be either attractive or repulsive.

- Gravitational forces are independent of the medium whereas electrostatic forces depend on the medium. This is due to the fact that a medium contains charges; the fast motion of these charges, in response to an external electromagnetic field, produces a large secondary electromagnetic field which should be accounted for. While slow motion of ordinary masses in response to changing gravitational field produces extremely weak secondary "gravimagnetic field" which may be neglected in most cases (except, of course, when mass moves with relativistic speeds).

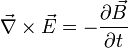

Time-varying fields

Charges do not only produce electric fields. As they move, they generate magnetic fields, and if the magnetic field changes, it generates electric fields. This "secondary" electric field can be computed using Faraday's law of induction,

where

indicates the curl of the electric field,

indicates the curl of the electric field, represents the vector rate of decrease of magnetic flux density with time.

represents the vector rate of decrease of magnetic flux density with time.

This means that a magnetic field changing in time produces a curled electric field, possibly also changing in time. The situation in which electric or magnetic fields change in time is no longer electrostatics, but rather electrodynamics or electromagnetics.