Economy of the United States

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Economics

Template:Economy of the United States

The economy of the United States has the world's largest gross domestic product (GDP), $13.21 trillion in 2006. It is a mixed economy where corporations and other private firms make the majority of microeconomic decisions while being regulated by the government. The US economy also maintains a high level of productivity ( GDP per capita), although it is not the world's highest. The U.S. economy has maintained a reasonably high overall GDP growth rate, a low unemployment rate, and high levels of research and capital investment. Major economic concerns in the United Sates include national debt, external debt, entitlement liabilities for retiring baby boomers who have already begun entering the Social Security system, consumer debt, a low savings rate, and a large current account deficit.

As at June 30, 2007, the gross U.S. external debt was $12 trillion or 88% of the overall size of the U.S. economy, (see List of countries by external debt). The gross public debt is 65% of GDP (also known as national debt and refers to what is owed by the combined public sector to both domestic and foreign creditors; see List of countries by public debt and global debt). The national debt includes the amount of the cumulative government deficits and interest.

History

With President Warren G. Harding's post–World War I "Return to Normalcy", the United States enjoyed a period of great prosperity during the 1920s. The stock market grew by leaps and bounds, fueled by easier access to stocks. However, the Great Depression ended that period. President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced an array of social programs and Public works, known collectively as the New Deal. The New Deal included a new social safety net involving relief programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Social Security system. In 1941, the U.S. entered World War II. The homefront saw enormous prosperity, as labor shortages brought millions of housewives, students, farmers and African Americans into the labor force. Millions moved to industrial centers in the North and West. Military spending accounted for over 40% of GDP at the peak, driving debt up to record levels.

The post–World War II years were a time of great prosperity in the United States. The economy remained stable until the 1970s, when the U.S. suffered stagflation. Richard Nixon took the United States off the Bretton Woods system, and further government attempts to revive the economy failed. As the decade progressed, the situation worsened. In November 1980, Robert G. Anderson wrote, "the death knell is finally sounding for the Keynesian Revolution." Ronald Reagan was elected President in 1980, and was of the opinion that "government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem." Reagan advocated a program of ' supply-side economics', and in 1981 Congress cut taxes and spending, and reduced regulations. Unfortunately as one might expect, cutting spending proved more difficult than cutting taxes, so there was a substantial increase of public debt. Although the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) declined by 2% in 1982, it proceeded to rebound, and by 1988 had enjoyed a total of 31% growth since Reagan's election. But economic policy did not correspond readily with any particular theory. The massive fiscal deficits of the Reagan era, like those of the later presidency of George W. Bush, had a predictable "Keynesian stimulus." On the other hand, in Reagan's first term, the Federal Reserve, trying to contain the stagflation of the 1970s that was linked in part to increases in the price of oil, raised interest rates to record levels, leading to a brief spike of the worst unemployment since the Great Depression.

In spite of the monetarist trend at the Federal Reserve, Keynesian income stabilization and redistribution programs, such as unemployment insurance and social security, have remained in effect, even though two decades of only partial minimum wage increases, adjusting for inflation, have left the lowest paid sector of the work force struggling to keep up. In sum, monetarists have been unable to dislodge the great "Keynesian institutions" of social security, unemployment insurance, Medicaid, and welfare payments, even though efforts have been made to curtail all of these programs (most notably welfare). These programs greatly exceed even military spending in the overall impact on the economy, a situation very different from the concluding years of World War II and into the 1950s, when Keynesian deficits were seen by some left-wing critics (e.g., Baran, Sweezy) as the economic policy of a nation that desperately needed military expenditure to keep unemployment down.

Notwithstanding the normative monetarist and "anti-big-government" themes associated with his Republican Party, President George W. Bush and both houses of the Republican-controlled Congress pushed through a massive expansion of the Medicaid entitlement program by extending coverage to prescription drugs. However the bulk of income redistribution and stabilization programs date from the New Deal of President Franklin Roosevelt and the Great Society of President Lyndon Johnson. Under Bill Clinton's eight years of presidency, the GDP expanded by 38%. By the end of his tenure the United States had a Gross National Income (GNI) of $9.7 trillion, and the lowest unemployment rates in 30 years. A recession began during 2001 in connection to the end of the dot-com bubble. Throughout, housing starts and purchases remained high, and the economy as of 2005 is considered by many to be strong in general.

Fundamental elements of the U.S. economy

A central feature of the U.S. economy is a reliance on private decision-making ("economic freedom") in economic decision-making. This is enhanced by relatively low levels of regulation, taxation, and government involvement, as well as a court system that generally protects property rights and enforces contracts. A large population, a large land area, numerous natural resources, a stable government and a highly developed system of post-secondary education are almost universally regarded as substantial contributors to U.S. economic performance.

The United States is rich in mineral resources and fertile farm soil, and it is fortunate to have a moderate climate. It also has extensive coastlines on both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, as well as on the Gulf of Mexico. Rivers flow from far within the continent, and the Great Lakes—five large, inland lakes along the U.S. border with Canada—provide additional shipping access. These extensive waterways have helped shape the country's economic growth over the years and helped bind America's 50 individual states together in a single economic unit.

The number of available workers and, more importantly, their productivity help determine the health of the U.S. economy. Throughout its history, the United States has experienced steady growth in the labor force, a phenomenon both cause and effect of almost constant economic expansion. Until shortly after World War I, most workers were immigrants from Europe, their immediate descendants, or African Americans who were mostly slaves taken from Africa, or slave descendants. Beginning in the early 20th century, many Latin Americans immigrated; followed by large numbers of Asians following removal of nation-origin based immigration quotas. The promise of high wages brings many highly skilled workers from around the world to the United States.

Labor mobility has also been important to the capacity of the American economy to adapt to changing conditions. When immigrants flooded labor markets on the East Coast, many workers moved inland, often to farmland waiting to be tilled. Similarly, economic opportunities in industrial, northern cities attracted black Americans from southern farms in the first half of the 20th century.

In the United States, the corporation has emerged as an association of owners, known as stockholders, who form a business enterprise governed by a complex set of rules and customs. Brought on by the process of mass production, corporations such as General Electric have been instrumental in shaping the United States. Through the stock market, American banks and investors have grown their economy by investing and withdrawing capital from profitable corporations. Today in the era of globalization American investors and corporations have influence all over the world. The American government has also been instrumental in investing in the economy, in areas such as providing cheap electricity (such as from the Hoover Dam), and military contracts in times of war.

While consumers and producers make most decisions that mold the economy, government activities have a powerful effect on the U.S. economy in at least four areas. Strong government regulation in the U.S. economy started in the early 1900s with the rise of the Progressive Movement; prior to this the government promoted economic growth through protective tariffs and subsidies to industry, built infrastructure, and established banking policies, including the gold standard, to encourage savings and investment in productive enterprises.

Monetary policy

us economics

A relatively independent central bank, known as the Federal Reserve, was formed in 1913 to provide a stable currency and monetary policy. The U.S. dollar has been regarded as the most stable currency in the world and many nations back their own currency with U.S. dollar reserves. During the last few years, the U.S. dollar has gradually depreciated in value and its reserve currency status is no longer as rock solid as previously.

The dollar has used gold standard and/or silver standard from 1785 until 1975, when it became a fiat currency.

Measuring the money supply

The most common measures are named M0 (narrowest), M1, M2, and M3. In the United States they are defined by the Federal Reserve as follows:

- M0: The total of all physical currency, plus accounts at the central bank that can be exchanged for physical currency.

- M1: M0 - those portions of M0 held as reserves or vault cash + the amount in demand accounts ("checking" or "current" accounts).

- M2: M1 + most savings accounts, money market accounts, and small denomination time deposits ( certificates of deposit of under $100,000).

- M3: M2 + all other CDs, deposits of eurodollars and repurchase agreements.

The Federal Reserve ceased publishing M3 statistics in March 2006, explaining that it costs a lot to collect the data but doesn't provide significantly useful information. The other three money supply measures continue to be provided in detail.

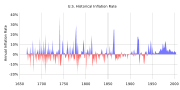

Inflation

The Federal Reserve tries to have a steady inflation rate of between two and three percent annually in order to prevent hoarding of dollars because, it is argued, currency hoarding can lead to an economic slowdown.

Stabilization and growth

The federal government attempts to use both monetary policy (control of the money supply through mechanisms such as changes in interest rates) and fiscal policy (taxes and spending) to maintain low inflation, high economic growth, and low unemployment.

For many years following the Great Depression of the 1930s, recessions—periods of slow economic growth and high unemployment—were viewed as the greatest of economic threats. When the danger of recession appeared most serious, government sought to strengthen the economy by spending heavily itself or cutting taxes so that consumers would spend more, and by fostering rapid growth in the money supply, which also encouraged more spending. In the 1970s, major price increases, particularly for energy, created a strong fear of inflation. As a result, government leaders came to concentrate more on controlling inflation than on combating recession by limiting spending, resisting tax cuts, and reining in growth in the money supply.

Ideas about the best tools for stabilizing the economy changed substantially between the 1960s and the 1990s. In the 1960s, government had great faith in fiscal policy—manipulation of government revenues to influence the economy. Since spending and taxes are controlled by the president and the U.S. Congress, these elected officials played a leading role in directing the economy. A period of high inflation, high unemployment, and huge government deficits weakened confidence in fiscal policy as a tool for regulating the overall pace of economic activity. Instead, monetary policy assumed growing prominence a piece.

Since the stagflation of the 1970s, the U.S. economy has been characterized by somewhat slower inflation. In 1985, the U.S. began its growing trade deficit with China.

In recent years, the primary economic concerns have centered around: high national debt ($9 trillion), high corporate debt ($9 trillion), high mortgage debt (over $10 trillion as of 2005 year-end), high unfunded Medicare liability ($30 trillion), high unfunded Social Security liability ($12 trillion), and high external debt (amount owed to foreign lenders), high trade deficits. In 2006, the U.S economy had its lowest saving rate since 1933. These issues have raised concerns among economists and unfunded liabilites and national politicians.

The U.S. economy maintains a relatively high GDP, a reasonably high GDP growth rate, and a low unemployment rate, making it attractive to immigrants worldwide.

Regulation and control

The U.S. federal government regulates private enterprise in numerous ways. Regulation falls into two general categories.

Economic regulation

Some efforts seek, either directly or indirectly, to control prices. Traditionally, the government has sought to prevent monopolies such as electric utilities from raising prices beyond the level that would ensure them reasonable profits. At times, the government has extended economic control to other kinds of industries as well. In the years following the Great Depression, it devised a complex system to stabilize prices for agricultural goods, which tend to fluctuate wildly in response to rapidly changing supply and demand. A number of other industries—trucking and, later, airlines—successfully sought regulation themselves to limit what they considered as harmful price cutting.

Another form of economic regulation, antitrust law, seeks to strengthen market forces so that direct regulation is unnecessary. The government—and, sometimes, private parties—have used antitrust law to prohibit practices or mergers that would unduly limit competition.

In 1933, Congress created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) which presently guarantees checking and savings deposits in member banks up to $100,000 per depositor to prevent bank failures. This was in response to the widespread bank runs of the early 1930s during the Great Depression.

Social regulations

Since the 1970s, government has also exercised control over private companies to achieve social goals, such as improving the public's health and safety or maintaining a healthy environment. For example, the Occupational Safety's and Health's Administration's provides and enforces standards for workplace safety, and in the case of the United States Environmental Protection Agency provides standards and regulations to maintain air, water, and land resources. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulates what drugs may reach the market, and also provides standards of disclosure for food products.

American attitudes about regulation changed substantially during the final three decades of the 20th century. Beginning in the 1970s, policy makers grew increasingly concerned that economic regulation protected inefficient companies at the expense of consumers in industries such as airlines and trucking. At the same time, technological changes spawned new competitors in some industries, such as telecommunications, that once were considered natural monopolies. Both developments led to a succession of laws easing regulation.

While leaders of America's two most influential political parties generally favored economic deregulation during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, there was less agreement concerning regulations designed to achieve social goals. Social regulation had assumed growing importance in the years following the Depression and World War II, and again in the 1960s and 1970s. During the 1980s, the government relaxed labor, consumer and environmental rules based on the idea that such regulation interfered with free enterprise, increased the costs of doing business, and thus contributed to inflation. The response to such changes is mixed; many Americans continued to voice concerns about specific events or trends, prompting the government to issue new regulations in some areas, including environmental protection. As of March 2005, it is estimated that compliance with government regulation costs the U.S. economy $5.69 trillion a year.

Where legislative channels have been unresponsive, some citizens have turned to the courts to address social issues more quickly. For instance, in the 1990s, individuals, and eventually the government itself, sued tobacco companies over the health risks of cigarette smoking. The 1998 Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement provided states with long-term payments to cover medical costs to treat smoking-related illnesses.

Direct services

Each level of government provides many direct services. The federal government, for example, is responsible for national defense, backs research that often leads to the development of new products, conducts space exploration, and runs numerous programs designed to help workers develop workplace skills and find jobs (including higher education). Government spending has a significant effect on local and regional economies—and even on the overall pace of economic activity.

State governments, meanwhile, are responsible for the construction and maintenance of most highways. State, county, or city governments play the leading role in financing and operating public schools. Local governments are primarily responsible for police and fire protection.

Overall, federal, state, and local spending accounted for almost 28% of gross domestic product in 1998.

Direct assistance

Government also provides many kinds of help to businesses and individuals. It offers low-interest loans and technical assistance to small businesses, and it provides loans to help students attend college. Government-sponsored enterprises buy home mortgages from lenders and turn them into securities that can be bought and sold by investors, thereby encouraging home lending. Government also actively promotes exports and seeks to prevent foreign countries from maintaining trade barriers that restrict imports.

Government supports individuals who cannot or will not adequately care for themselves. Social Security, which is financed by a tax on employers and employees, accounts for the largest portion of Americans' retirement income. The Medicare program pays for many of the medical costs of the elderly. The Medicaid program finances medical care for low-income families. In many states, government maintains institutions for the mentally ill or people with severe disabilities. The federal government provides food stamps to help poor families obtain food, and the federal and state governments jointly provide welfare grants to support low-income parents with children.

Many of these programs, including Social Security, trace their roots to the New Deal programs of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who served as the U.S. president from 1933 to 1945.

Many other assistance programs for individuals and families, including Medicare and Medicaid, were begun in the 1960s during President Lyndon Johnson's (1963–1969) War on Poverty. Although some of these programs encountered financial difficulties in the 1990s and various reforms were proposed, they continued to have strong support from both of the United States' major political parties. Critics argued, however, that providing welfare to unemployed but healthy individuals actually created dependency rather than solving problems. Welfare reform legislation (the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act) passed in 1996 under President Bill Clinton (1993–2001) and a Republican Congress requires people to work, job search, enter training, or receive education as a condition of receiving benefits and imposes federal limits on how long individuals may receive payments (states may adopt stronger limits).

National debt

The national debt, also known as the U.S. public debt (part of which is the gross federal debt), is the overall collective sum of yearly budget deficit owed by all branches of the United States government, plus interest. The economic significance of this debt and its potential ramifications for future generations of Americans are controversial issues in the United States.

The borrowing cap debt ceiling as of 2005 stood at $8.18 trillion. . In March 2006, Congress raised that ceiling an additional $0.79 trillion to $8.97 trillion, which is approximately 68% of GDP. Congress has used this method to deal with an encroaching debt ceiling in previous years, as the federal borrowing limit was raised in 2002 and 2003.

While the U.S. national debt is the world's largest in absolute size, a more accurate measure is that of its size relative to the nation's GDP. When the national debt is put into this perspective it appears considerably less today than in past years, particularly during World War II. By this measure, it is also considerably less than those of other industrialized nations such as Japan and roughly equivalent to those of several Western European nations.

External debt: Liabilities to foreigners

Gross U.S. liabilities to foreigners are $16.3 trillion as at end 2006.(over 100% of GDP). The U.S. Net International Investment Position (NIIP) deteriorated to a negative $2.5 trillion at the end of 2006, or about minus 19% of GDP.

This figure rises as long as the US maintains an imbalance in trade, specifically, when the value of imports substantially outweighs the value of exports. It should be noted that this external debt does not, for the most part, represent lending to Americans or the American government, nor is it consumer debt owed to non-US creditors. Rather, the external debt is an accounting entry that largely represents US domestic assets purchased with trade dollars and owned overseas, largely by US trading partners. However, this is not the whole picture, as foreign holdings of government debt currently amount to about 27% of the total, or some 2 trillion dollars.

For countries like the United States, a large net external debt is created when the value of foreign assets (debt and equity) held by domestic residents is less than the value of domestic assets held by foreigners. In simple terms, as foreigners buy property in the US, this adds to the external debt. When this occurs in greater amounts than Americans buying property overseas, nations like the United States are said to be debtor nations, but this is not conventional debt like a loan obtained from a bank. However, foreigners also purchase U.S. debt instruments, such as government bonds, which are forms of conventional debt.

If the external debt represents foreign ownership of domestic assets, the result is that rental income, stock dividends, capital gains and other investment income is received by foreign investors, rather than by US residents. On the other hand, when US debt is held by overseas investors, they receive interest and principal repayments. As the trade imbalance puts extra dollars in hands outside of the US, these dollars may be used to invest in new assets (foreign direct investment, such as new plants) or be used to buy existing US assets such as stocks, real estate and bonds. With a mounting trade deficit, the income from these assets increasingly transfers overseas.

Of major concern is the fact that the magnitude of the NIIP (or net external debt) is quite a bit larger than most national economies. Fueled by the sizable trade deficit, the external debt is so large that many wonder if the trade situation can be sustained in the long term. Complicating the matter is that many of America's trading partners, such as China, depend for much of their entire economy on exports, and especially exports to America. Many controversies exist about the current trade and external debt situation, and it is arguable whether anyone understands how these dynamics will play out in an historically unprecedented floating exchange rate system. While various aspects of the U.S. economic profile have precedents in the situations of other countries (notably government debt as a percentage of GDP), the sheer size of the US, and the integral role of the US economy in the overall global economic environment, create considerable uncertainty about the future.

International trade

The United States is the most significant nation in the world when it comes to international trade. For decades, it has led the world in imports while simultaneously remaining as one of the top three exporters of the world.

As the major epicenter of world trade, the United States enjoys leverage that many other nations do not. For one, since it is the world's leading consumer, it is the number one customer of companies all around the world. Many businesses compete for a share of the United States market. In addition, the United States occasionally uses its economic leverage to impose economic sanctions in different regions of the world. USA is the top export market for almost 60 trading nations worldwide.

The U.S. is a member of several international trade organizations. The purpose of joining these organizations is to come to agreement with other nations on trade issues, although there is some disagreement among U.S. citizens as to whether or not the U.S. government should be making these trade agreements in the first place.

Since it is the world's leading importer, there are many U.S. dollars in circulation all around the planet. The stable U.S. economy and fairly sound monetary policy has led to faith in the U.S. dollar as the world's most stable currency, although that may be changing in recent times.

In order to fund the national debt (also known as public debt), the United States relies on selling U.S. treasury bonds to people both inside and outside the country, and in recent times the latter have become increasingly important. Much of the money generated for the treasury bonds came from U.S. dollars which were used to purchase imports in the United States.

US exports of goods in 2004 by country

| Nation | millions of dollars | percentage | cumulative percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 189101 | 23.1192% | 23.1192% |

| Mexico | 110775 | 13.5432% | 36.6624% |

| Japan | 54400 | 6.6509% | 43.3133% |

| United Kingdom | 35960 | 4.3964% | 47.7097% |

| China | 34721 | 4.2449% | 51.9546% |

| Germany | 31381 | 3.8366% | 55.7912% |

| Korea | 26333 | 3.2194% | 59.0106% |

| Netherlands | 24286 | 2.9692% | 61.9798% |

| Taiwan | 21731 | 2.6568% | 64.6366% |

| France | 21240 | 2.5968% | 67.2334% |

| Singapore | 19601 | 2.3964% | 69.6298% |

| Belgium | 16877 | 2.0634% | 71.6931% |

| Hong Kong | 15809 | 1.9328% | 73.6259% |

| Australia | 14271 | 1.7448% | 75.3707% |

| Brazil | 13863 | 1.6949% | 77.0655% |

| Malaysia | 10897 | 1.3323% | 78.3978% |

| Italy | 10711 | 1.3095% | 79.7073% |

| Switzerland | 9268 | 1.1331% | 80.8404% |

| Israel | 9198 | 1.1245% | 81.9649% |

| Ireland | 8166 | 0.9984% | 82.9633% |

| Philippines | 7072 | 0.8646% | 83.8279% |

| Spain | 6641 | 0.8119% | 84.6398% |

| Thailand | 6363 | 0.7779% | 85.4177% |

| India | 6095 | 0.7452% | 86.1629% |

| Saudi Arabia | 5245 | 0.6412% | 86.8042% |

| Venezuela | 4782 | 0.5846% | 87.3888% |

| Colombia | 4504 | 0.5507% | 87.9394% |

| Dominican Republic | 4343 | 0.5310% | 88.4704% |

| United Arab Emirates | 4064 | 0.4969% | 88.9673% |

| Chile | 3625 | 0.4432% | 89.4105% |

| Argentina | 3386 | 0.4140% | 89.8244% |

| Turkey | 3361 | 0.4109% | 90.2353% |

| Costa Rica | 3304 | 0.4039% | 90.6393% |

| Sweden | 3265 | 0.3992% | 91.0385% |

| South Africa | 3172 | 0.3878% | 91.4263% |

| Egypt | 3105 | 0.3796% | 91.8059% |

| Others | 67023 | 8.19% | 100% |

| Total Exports of Goods: | 817,939 |

US imports of goods in 2004 by country

| Country | Millions of dollars | Percentage | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 255928 | 17.41401% | 17.41401% |

| China | 196699 | 13.38392% | 30.79793% |

| Mexico | 155843 | 10.60397% | 41.40190% |

| Japan | 129595 | 8.81798% | 50.21988% |

| Germany | 77236 | 5.25534% | 55.47522% |

| United Kingdom | 46402 | 3.15731% | 58.63253% |

| Korea | 46163 | 3.14105% | 61.77359% |

| Taiwan, ROC | 34617 | 2.35543% | 64.12902% |

| France | 31814 | 2.16471% | 66.29373% |

| Malaysia | 28185 | 1.91778% | 68.21151% |

| Italy | 28089 | 1.91125% | 70.12276% |

| Ireland | 27442 | 1.86723% | 71.98998% |

| Venezuela | 24962 | 1.69848% | 73.68846% |

| Brazil | 21157 | 1.43958% | 75.12804% |

| Saudi Arabia | 20924 | 1.42372% | 76.55176% |

| Thailand | 17577 | 1.19599% | 77.74775% |

| Nigeria | 16246 | 1.10542% | 78.85317% |

| India | 15562 | 1.05888% | 79.91205% |

| Singapore | 15306 | 1.04146% | 80.95351% |

| Israel | 14527 | 0.98846% | 81.94196% |

| Sweden | 12687 | 0.86326% | 82.80522% |

| Netherlands | 12605 | 0.85768% | 83.66290% |

| Belgium | 12448 | 0.84699% | 84.50989% |

| Russia | 11847 | 0.80610% | 85.31599% |

| Switzerland | 11643 | 0.79222% | 86.10821% |

| Indonesia | 10811 | 0.73561% | 86.84382% |

| Hong Kong | 9314 | 0.63375% | 87.47757% |

| Philippines | 9144 | 0.62218% | 88.09975% |

| Iraq | 8514 | 0.57931% | 88.67907% |

| Australia | 7544 | 0.51331% | 89.19238% |

| Spain | 7476 | 0.50869% | 89.70107% |

| Algeria | 7409 | 0.50413% | 90.20520% |

| Colombia | 7290 | 0.49603% | 90.70123% |

| others | 136,661 | 9.29877% | 100% |

| Total Imports: | 1,469,667 |

Distribution of wealth

The total value of all U.S. household wealth in 2000 was approximately $44 trillion.

| Family net worth, by selected characteristics of families, 1989-2004 surveys | ||||||||||||

| Thousands of 2004 dollars | ||||||||||||

| Family characteristic | 1989 | 1992 | 1995 | 1998 | 2001 | 2004 | ||||||

| Median | Mean | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | |

| All Families | 68.8 | 272.6 | 65.2 | 245.7 | 70.8 | 260.8 | 83.1 | 327.5 | 92.2 | 422.9 | 93.1 | 448.2 |

| Percentiles of income | ||||||||||||

| Less than 20 | 2.6 | 36.2 | 5.2 | 43.4 | 7.4 | 54.7 | 6.8 | 55.4 | 8.4 | 56.2 | 7.5 | 72.6 |

| 20-39.9 | 35.3 | 96.4 | 36.6 | 84.6 | 41.3 | 97.4 | 38.4 | 111.4 | 39.9 | 122.7 | 33.7 | 121.5 |

| 40-59.9 | 61.1 | 148.5 | 52.1 | 133.3 | 57.1 | 126.0 | 61.9 | 146.6 | 67.8 | 173.3 | 72.0 | 194.6 |

| 60-79.9 | 97.5 | 199.3 | 99.3 | 185.4 | 93.6 | 198.5 | 130.2 | 238.3 | 152.6 | 313.2 | 160.0 | 340.8 |

| 80-89.9 | 193.5 | 326.1 | 151.8 | 297.1 | 157.7 | 316.8 | 218.5 | 377.1 | 280.3 | 487.0 | 313.3 | 487.4 |

| 90-100 | 569.5 | 1,438.5 | 479.3 | 1,266.0 | 436.9 | 1,338.0 | 524.4 | 1,793.9 | 887.9 | 2,410.9 | 924.1 | 2,534.6 |

| Age of head (years) | ||||||||||||

| Less than 35 | 11.4 | 68.7 | 12.0 | 59.7 | 14.8 | 53.2 | 10.6 | 74.0 | 12.5 | 96.6 | 14.2 | 73.5 |

| 35-44 | 82.7 | 216.4 | 58.7 | 175.5 | 64.2 | 176.8 | 73.5 | 227.6 | 82.6 | 276.6 | 69.4 | 299.2 |

| 45-54 | 144.8 | 405.1 | 103.1 | 353.3 | 116.8 | 364.8 | 122.5 | 420.2 | 141.6 | 517.6 | 144.7 | 542.7 |

| 55-64 | 143.5 | 451.2 | 150.2 | 445.4 | 141.9 | 471.0 | 148.2 | 617.0 | 197.4 | 779.5 | 248.7 | 843.8 |

| 65-74 | 112.4 | 410.2 | 130.0 | 377.6 | 136.6 | 429.3 | 169.8 | 541.1 | 189.4 | 722.6 | 190.1 | 690.9 |

| 75 or more | 106.2 | 354.2 | 114.5 | 282.3 | 114.5 | 317.9 | 145.6 | 360.3 | 165.4 | 499.6 | 163.1 | 528.1 |

| Education of head | ||||||||||||

| No high school diploma | 35.3 | 121.8 | 24.6 | 92.4 | 27.9 | 103.7 | 24.5 | 91.4 | 27.2 | 110.8 | 20.6 | 136.5 |

| High school diploma | 54.0 | 163.3 | 50.7 | 147.1 | 63.9 | 163.7 | 62.7 | 182.9 | 61.8 | 193.0 | 68.7 | 196.8 |

| Some college | 67.4 | 273.3 | 76.0 | 226.0 | 57.6 | 232.3 | 85.6 | 275.5 | 77.5 | 305.7 | 69.3 | 308.6 |

| College degree | 162.8 | 530.2 | 129.4 | 447.5 | 128.6 | 473.6 | 169.7 | 612.3 | 227.2 | 848.0 | 226.1 | 851.3 |

| Race or ethnicity of respondent | ||||||||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 104.2 | 333.4 | 91.9 | 292.9 | 94.3 | 308.7 | 111.0 | 391.1 | 130.2 | 520.2 | 140.7 | 561.8 |

| Nonwhite or Hispanic | 9.8 | 92.1 | 15.8 | 102.0 | 19.5 | 94.9 | 19.3 | 116.5 | 19.1 | 125.1 | 24.8 | 153.1 |

| Current work status of head | ||||||||||||

| Working for someone else | 55.7 | 166.7 | 51.6 | 161.0 | 60.3 | 168.4 | 61.2 | 194.8 | 69.3 | 240.3 | 67.2 | 268.5 |

| Self-employed | 248.7 | 955.2 | 190.2 | 790.6 | 191.8 | 862.7 | 288.0 | 1,071.3 | 375.2 | 1,342.9 | 335.6 | 1,423.2 |

| Retired | 96.9 | 267.9 | 92.9 | 250.1 | 99.9 | 277.2 | 131.0 | 356.5 | 123.1 | 483.6 | 139.8 | 469.0 |

| Other not working | 1.2 | 57.6 | 4.3 | 70.0 | 4.5 | 70.1 | 4.1 | 85.8 | 9.5 | 192.3 | 11.8 | 162.3 |

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Northeast | 128.1 | 316.1 | 84.5 | 277.2 | 102.0 | 308.9 | 109.3 | 351.3 | 99.3 | 483.2 | 161.7 | 569.1 |

| Midwest | 77.0 | 274.8 | 75.1 | 228.1 | 80.8 | 244.7 | 93.1 | 288.5 | 113.3 | 363.3 | 115.0 | 436.1 |

| South | 51.7 | 192.8 | 45.5 | 185.5 | 54.2 | 229.5 | 71.0 | 309.6 | 78.6 | 400.6 | 63.8 | 348.0 |

| West | 67.2 | 360.0 | 94.2 | 335.4 | 67.4 | 286.1 | 71.1 | 379.1 | 93.4 | 470.4 | 94.8 | 523.7 |

| Housing status | ||||||||||||

| Owner | 147.1 | 394.8 | 130.2 | 355.7 | 128.1 | 373.7 | 153.2 | 468.7 | 183.8 | 596.9 | 184.4 | 624.9 |

| Renter or other | 2.9 | 56.3 | 4.2 | 50.9 | 6.0 | 53.8 | 4.9 | 50.4 | 5.1 | 58.6 | 4.0 | 54.1 |

| Percentiles of net worth | ||||||||||||

| Less than 25 | 0.3 | -0.9 | 0.6 | -0.8 | 1.2 | -0.2 | 0.6 | -2.1 | 1.2 | † | 1.7 | -1.4 |

| 25-49.9 | 30.9 | 33.7 | 30.9 | 33.4 | 34.7 | 37.6 | 37.9 | 41.6 | 43.5 | 47.2 | 43.6 | 47.1 |

| 50-74.9 | 127.0 | 130.4 | 115.4 | 119.2 | 117.1 | 122.6 | 139.7 | 149.1 | 168.2 | 177.9 | 170.7 | 185.4 |

| 75-89.9 | 308.2 | 331.2 | 268.5 | 287.4 | 272.3 | 293.6 | 357.7 | 372.7 | 458.8 | 480.7 | 506.8 | 526.7 |

| 90-100 | 1,009.5 | 1,820.7 | 876.2 | 1,645.8 | 836.7 | 1,766.7 | 1,039.1 | 2,244.2 | 1,388.5 | 2,944.3 | 1,430.1 | 3,114.2 |

| Note: See note to table 1. † Less than 0.05 ($50). | ||||||||||||

Distribution of income

| Before-Tax Family Income in the U.S. from 1989-2004 | |||||||

| (thousands of 2004 dollars) | |||||||

| before tax family income (mean) | |||||||

| Percentiles of net worth | 1989 | 1992 | 1995 | 1998 | 2001 | 2004 | |

| 90-100 | 205.1 | 158.5 | 172.8 | 206.3 | 272.7 | 256.2 | |

| 75-89.9 | 74.6 | 67.0 | 65.0 | 78.3 | 83.7 | 87.9 | |

| 50-74.9 | 52.9 | 48.1 | 50.1 | 54.3 | 62.7 | 60.6 | |

| 25-49.9 | 36.9 | 36.4 | 38.6 | 39.3 | 42.1 | 42.2 | |

| Less than 25 | 21.5 | 22.9 | 22.9 | 23.6 | 25.6 | 25.1 | |

| before tax family income (median) | |||||||

| Percentiles of net worth | 1989 | 1992 | 1995 | 1998 | 2001 | 2004 | |

| 90-100 | 114.7 | 106.6 | 99.1 | 102.4 | 134.7 | 143.8 | |

| 75-89.9 | 61.2 | 56.7 | 52.6 | 65.8 | 74.1 | 77.0 | |

| 50-74.9 | 46.3 | 43.2 | 43.6 | 47.0 | 54.4 | 52.4 | |

| 25-49.9 | 32.3 | 32.2 | 35.3 | 35.3 | 37.2 | 37.0 | |

| Less than 25 | 15.3 | 17.2 | 17.8 | 18.5 | 21.0 | 20.5 |

Private income

| Median income levels | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Households | Persons, age 25 or older with earnings | Household income by race | |||||||

| All households | Dual earner households |

Per household member |

Males | Females | Both sexes | Asian | White, non-hispanic |

Hispanic | Black |

| $46,326 | $67,348 | $23,535 | $39,403 | $26,507 | $32,140 | $57,518 | $48,977 | $34,241 | $30,134 |

| Median personal income by educational attainment | |||||||||

| Measure | Some High School | High school graduate | Some college | Associate degree | Bachelor's degree or higher | Bachelor's degree | Master's degree | Professional degree | Doctorate degree |

| Persons, age 25+ w/ earnings | $20,321 | $26,505 | $31,054 | $35,009 | $49,303 | $43,143 | $52,390 | $82,473 | $70,853 |

| Male, age 25+ w/ earnings | $24,192 | $32,085 | $39,150 | $42,382 | $60,493 | $52,265 | $67,123 | $100,000 | $78,324 |

| Female, age 25+ w/ earnings | $15,073 | $21,117 | $25,185 | $29,510 | $40,483 | $36,532 | $45,730 | $66,055 | $54,666 |

| Persons, age 25+, employed full-time | $25,039 | $31,539 | $37,135 | $40,588 | $56,078 | $50,944 | $61,273 | $100,000 | $79,401 |

| Household | $22,718 | $36,835 | $45,854 | $51,970 | $73,446 | $68,728 | $78,541 | $100,000 | $96,830 |

| Household income distribution | |||||||||

| Bottom 10% | Bottom 20% | Bottom 25% | Middle 33% | Middle 20% | Top 25% | Top 20% | Top 5% | Top 1.5% | Top 1% |

| $0 to $10,500 | $0 to $18,500 | $0 to $22,500 | $30,000 to $62,500 | $35,000 to $55,000 | $77,500 and up | $92,000 and up | $167,000 and up | $250,000 and up | $350,000 and up |

| SOURCE: US Census Bureau, 2006; income statistics for the year 2005 | |||||||||

International comparison

| Country | Median household income national currency units | Year | PPP rate (OECD) | Median household income (PPP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switzerland | 95,184 CHF | 2005 | 1.74 | $55,000 |

| California, US | US State | $54,000 | ||

| United States | $48,000 USD | 2006 | 1.00 | $48,000 |

| Canada | $53,634 CAD | 2005 | 1.21 | $44,000 |

| New Zealand | $62,556 NZD | 2007 | 1.54 | $41,000 |

| United Kingdom | £24,700 GBP | 2004 | 0.632 | $39,000 |

| Australia | $53,404 AUD | 2006 | 1.41 | $38,000 |

| Israel | ₪107,820 ILS | 2006 | 2.90 | $37,000 |

| Ireland | €35,410 EUR | 2005 | 1.02 | $35,000 |

| Scotland, United Kingdom |

£21,892 GBP | 2005 | 0.649 | $34,000 |

| West Virginia, US | US state | $33,000 | ||

| Hong Kong | $186,000 HKD | 2005 | 5.96 | $31,000 |

| Singapore | $45,960 SGD | 2005 | 1.55 | $30,000 |

Poverty

There is significant disagreement about poverty in the United States, particularly over how poverty ought to be defined. Using radically different definitions, two major groups of advocates have claimed variously that (a) the United States has eliminated poverty over the last century; or (b) it has such a severe poverty crisis that it ought to devote significantly more resources to the problem. The debate includes how poverty should be defined.

Measures of poverty can be either absolute or relative. Absolute poverty is defined in real dollar values, whereas relative poverty is a comparison of the highest to the lowest standard of living at a particular time period.

Income inequality

The United Nations Development Programme Report 2006 on income equality ranks the United States as tied for 73rd out of 126 countries, as measured by the Gini coefficient. The richest 10% make 15.9 times as much as the poorest 10%, and the richest 20% make 8.4 times as much as the poorest 20%. Among the world's industrialized countries, the U.S. has a very high degree of inequality. In particular it is higher than that of the other major industrialized economies such as Japan, the UK, Germany, France, and Italy. (See List of countries by income equality.)

Unemployment

Other statistics

Industrial production growth rate: 3.2% (2005 est.)

Electricity:

- production: 3.979 trillion kWh (2004)

- consumption: 3.717 trillion kWh (2004)

- exports: 22.9 billion kWh (2004)

- imports: 34.21 billion kWh (2004)

Electricity - production by source:

- fossil fuel: 71.6%

- hydro: 5.6%

- nuclear: 20.6%

- other: 2.3% (2001)

Oil:

- production: 7.61 million barrel/day (2005 est.)

- consumption: 20.03 million barrel/day (2003 est.)

- exports: 1.048 million barrel/day (2004 est.)

- imports: 13.15 million barrel/day (2004 est.)

- net imports: 12.097 million barrel/day (2004 est.)

- proved reserves: 22.45 billion barrel (1 January 2002)

Natural gas:

- production: 531.1 billion cu m (2004 est.)

- consumption: 635.1 billion cu m (2004 est.)

- exports: 24.18 billion cu m (2004 est.)

- imports: 120.6 billion cu m (2004 est.)

- proved reserves: 5.451 trillion cu m (1 January 2005 est.)

Agriculture - products: wheat, corn, other grains, fruits, vegetables, cotton; beef, pork, poultry, dairy products; forest products; fish

Exports - commodities: capital goods, automobiles, industrial supplies and raw materials, consumer goods, agricultural products

Imports - commodities: crude oil and refined petroleum products, machinery, automobiles, consumer goods, industrial raw materials, food and beverages

Historic exchange rates:

-

Jan 2007 Jan 2006 Jan 2005 Jan 2004 Jan 2003 Jan 2002 2001* 2000* 1999* 1998 1997 Canadian dollars per U.S. dollar 1.165 1.164 1.204 1.293 1.576 1.600 1.548 1.485 1.485 1.483 1.384 Japanese yen per U.S. dollar 119.0 118.1 102.5 107.2 118.7 132.6 121.5 107.7 113.9 130.9 120.9 Euros per US dollar .7577 .8444 .7387 .7939 .9534 1.128 1.062 .9947 .8557 - - British pounds per U.S. dollar 0.5104 0.5812 0.5209 0.5600 0.6212 0.6981 0.6944 0.6596 0.6180 0.6037 0.6106 French francs per U.S. dollar - - - - - - - - 5.65 5.899 5.836 Italian lire per U.S. dollar - - - - - - - - 1,668.7 1,763.2 1,703.1 German deutschmarks per U.S. dollar - - - - - - - - 1.69 1.969 1.734 Note: financial institutions in France, Italy, Germany, and eight other European countries started using the euro on 1 January 1999, with the euro replacing the local currency for all transactions in 2002. Their 1999 figures are for January. *January 1 exchange rates

US related topics

Template:US topics