Phosphorus

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Chemical elements

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name, symbol, number | phosphorus, P, 15 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical series | nonmetals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group, period, block | 15, 3, p | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | waxy white/ red/ black/ colorless/ yellow  |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight | 30.973762 (2) g·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s2 3p3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | (white) 1.823 g·cm−3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | (red) 2.34 g·cm−3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | (black) 2.69 g·cm−3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | (white) 317.3 K (44.2 ° C, 111.6 ° F) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 550 K (277 ° C, 531 ° F) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | (white) 0.66 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 12.4 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Specific heat capacity | (25 °C) (white) 23.824 J·mol−1·K−1 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 5, 4, 3, 2 , 1 , -3 (mildly acidic oxide) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | 2.19 (Pauling scale) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies ( more) |

1st: 1011.8 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd: 1907 kJ·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd: 2914.1 kJ·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | 100 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius (calc.) | 98 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 106 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 180 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | no data | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | (300 K) (white) 0.236 W·m−1·K−1 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 11 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS registry number | 7723-14-0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Selected isotopes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| References | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Phosphorus, (IPA: /ˈfɒsfərəs/), is the chemical element that has the symbol P and atomic number 15. The name comes from the Greek: phôs (meaning "light") and phoros (meaning "bearer"). A multivalent nonmetal of the nitrogen group, phosphorus is commonly found in inorganic phosphate rocks.

Due to its high reactivity, phosphorus is never found as a free element in nature on Earth. One form of phosphorus (white phosphorus) emits a faint glow upon exposure to oxygen (hence its Greek derivation and the Latin 'light-bearer', meaning the planet Venus as Hesperus or "Morning Star").

Phosphorus is a component of DNA and RNA and an essential element for all living cells. The most important commercial use of phosphorus-based chemicals is the production of fertilizers.

Phosphorus compounds are also widely used in explosives, nerve agents, friction matches, fireworks, pesticides, toothpaste, and detergents.

Characteristics

Allotropes

Phosphorus is an excellent example of an element that exhibits allotropy, as its various allotropes have strikingly different properties.

The two most common allotropes are white phosphorus and red phosphorus. A third form, scarlet phosphorus, is obtained by allowing a solution of white phosphorus in carbon disulfide to evaporate in sunlight. A fourth allotrope, black phosphorus, is obtained by heating white phosphorus under very high pressures (12,000 atmospheres). In appearance, properties and structure it is very like graphite, being black and flaky, a conductor of electricity and has puckered sheets of linked atoms. Another allotrope is diphosphorus - which is highly reactive.

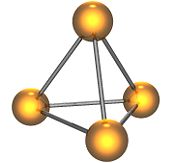

White phosphorus (P4) exists as individual molecules made up of four atoms in a tetrahedral arrangement, resulting in very high ring strain and instability. It contains 6 single bonds.

White phosphorus is a white, waxy transparent solid. This allotrope is thermodynamically unstable at normal condition and will gradually change to red phosphorus. This transformation, which is accelerated by light and heat, makes white phosphorus almost always contain some red phosphorus and appear yellow. For this reason, it is also called yellow phosphorus. It glows greenish in the dark (when exposed to oxygen), is highly flammable and pyrophoric (self-igniting) upon contact with air as well as toxic (causing severe liver damage on ingestion). The odour of combustion of this form has a characteristic garlic smell, and samples are commonly coated with white "(di) phosphorus pentoxide", which consists of P4O10 tetrahedra with oxygen inserted between the phosphorus atoms and at their vertices. White phosphorus is insoluble in water but soluble in carbon disulfide.

The white allotrope can be produced using several different methods. In one process, calcium phosphate, which is derived from phosphate rock, is heated in an electric or fuel-fired furnace in the presence of carbon and silica. Elemental phosphorus is then liberated as a vapour and can be collected under phosphoric acid. This process is similar to the first synthesis of phosphorus from calcium phosphate in urine.

Red phosphorus may be formed by heating white phosphorus to 250°C (482°F) or by exposing white phosphorus to sunlight. Phosphorus after this treatment exists as an amorphous network of atoms which reduces strain and gives greater stability; further heating results in the red phosphorus becoming crystalline. Red phosphorus does not catch fire in air at temperatures below 240°C, whereas white phosphorus ignites at about 30°C.

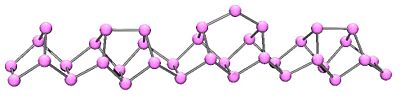

In 1865 Hittorf discovered that when phosphorus was recrystallized from molten lead, a red/purple form is obtained. This purple form is sometimes known as "Hittorf's phosphorus." In addition, a fibrous form exists with similar phosphorus cages. Below is shown a chain of phosphorus atoms which exhibits both the purple and fibrous forms.

One of the forms of red/black phosphorus is a cubic solid.

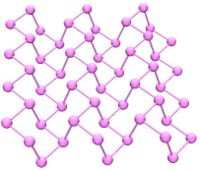

Black phosphorus has an orthorhombic structure (Cmca) and is the least reactive allotrope, it consists of many six-membered rings which are interlinked. Each atom is bonded to three other atoms. A recent synthesis of black phosphorus using metal salts as catalysts has been reported.

The diphosphorus allotrope (P2) can be obtained normally only under extreme conditions (for example, from P4 at 1100 kelvin). Nevertheless, some advancements were obtained in generating the diatomic molecule in homogeneous solution, under normal conditions with the use by some transitional metal complexes (based on for example tungsten and niobium).

Glow

The glow from phosphorus was the attraction of its discovery around 1669, but the mechanism for that glow was not fully described until 1974. It was known from early times that the glow would persist for a time in a stoppered jar but then cease. Robert Boyle in the 1680s ascribed it to "debilitation" of the air; in fact it is oxygen being consumed. By the 18th century it was known that in pure oxygen phosphorus does not glow at all, there is only a range of partial pressure where it does. Heat can be applied to drive the reaction at higher pressures.

In 1974 the glow was explained by R. J. van Zee and A. U. Khan. A reaction with oxygen takes place at the surface of the solid (or liquid) phosphorus, forming the short-lived molecules HPO and P2O2 that both emit visible light. The reaction is slow and only very little of the intermediates is required to produce the luminescence, hence the extended time the glow continues in a stoppered jar.

Although the term phosphorescence is derived from phosphorus, the reaction which gives phosphorus its glow is properly called luminescence (glowing by its own reaction, in this case chemoluminescence), not phosphorescence (re-emitting light that previously fell on it).

Isotopes

Radioactive isotopes of phosphorus include

- 32P; a beta-emitter (1.71 MeV) with a half-life of 14.3 days which is used routinely in life-science laboratories, primarily to produce radiolabeled DNA and RNA probes, e.g. for use in Northern blots or Southern blots. Because the high energy beta particles produced penetrate skin and corneas, and because any 32P ingested, inhaled, or absorbed is readily incorporated into bone and nucleic acids, Occupational Safety and Health Administration requires that a lab coat, disposable gloves, and safety glasses or goggles be worn when working with 32P, and that working directly over an open container be avoided in order to protect the eyes. Monitoring personal, clothing, and surface contamination is also required. In addition, due to the high energy of the beta particles, shielding this radiation with the normally used dense materials (e.g. lead), gives rise to secondary emission of X-rays via a process known as Bremsstrahlung, meaning braking radiation. Therefore shielding must be accomplished with low density materials, e.g. Plexiglas, Lucite, plastic, wood, or water.

- 33P; a beta-emitter (0.25 MeV) with a half-life of 25.4 days. It is used in life-science laboratories in applications in which lower energy beta emissions are advantageous such as DNA sequencing.

Occurrence

Due to its reactivity with air and many other oxygen-containing substances, phosphorus is not found free in nature but it is widely distributed in many different minerals.

Phosphate rock, which is partially made of apatite (an impure tri-calcium phosphate mineral), is an important commercial source of this element. About 50 per cent of the global phosphorus reserves are in the Arab nations. Large deposits of apatite are located in China, Russia, Morocco, Florida, Idaho, Tennessee, Utah, and elsewhere. Albright and Wilson in the United Kingdom and their Niagara Falls plant, for instance, were using phosphate rock in the 1890s and 1900s from Connetable, Tennessee and Florida; by 1950 they were using phosphate rock mainly from Tennessee and North Africa. In the early 1990s Albright and Wilson's purified wet phosphoric acid business was being affected by phosphate rock sales by China and the entry of their long standing Moroccan phosphate suppliers into the purified wet phosphoric acid business.

At today's rate of consumption, the supply of phosphorus is estimated to run out in 345 years.

Compounds

- Hydride: PH3

- Halides: PBr5, PBr3, PCl3, PI3

- Oxides: P4O6, P4O10

- Sulfides: P2S5, P4S3

- Acids: H3PO2, H3PO4

- Phosphates: (NH4)3PO4, Ca3(PO4)2), FePO4, Fe3(PO4)2, Na3PO4, Ca(H2PO4)2, KH2PO4

- Phosphides: Ca3P2, GaP, Zn3P2

- Organophosphorus and organophosphates: Lawesson's reagent, Parathion, Sarin, Soman, Tabun, Triphenyl phosphine, VX nerve gas

As an exception to the octet rule

The simple Lewis structure for the trigonal bipyramidal PCl5 molecule contains five covalent bonds, implying a hypervalent molecule with ten valence electrons contrary to the octet rule.

An alternate description of the bonding, however, respects the octet rule by using 3-centre-4-electron (3c-4e) bonds. In this model the octet on the P atom corresponds to six electrons which form three Lewis (2c-2e) bonds to the three equatorial Cl atoms, plus the two electrons in the 3-centre Cl-P-Cl bonding molecular orbital for the two axial Cl electrons. The two electrons in the corresponding nonbonding molecular orbital are not included because this orbital is localized on the two Cl atoms and does not contribute to the electron density on P.

Applications

Concentrated phosphoric acids, which can consist of 70% to 75% P2O5, are very important to agriculture and farm production in the form of fertilisers. Global demand for fertilizers led to large increases in phosphate (PO43-) production in the second half of the 20th century. Other uses;

- Phosphates are utilized in the making of special glasses that are used for sodium lamps.

- Bone-ash, calcium phosphate, is used in the production of fine china.

- Sodium tripolyphosphate made from phosphoric acid is used in laundry detergents in several countries, and banned for this use in others.

- Phosphoric acid made from elemental phosphorus is used in food applications such as soda beverages. The acid is also a starting point to make food grade phosphates. These include mono-calcium phosphate which is employed in baking powder and sodium tripolyphosphate and other sodium phosphates. Among other uses these are used to improve the characteristics of processed meat and cheese. Others are used in toothpaste. Trisodium phosphate is used in cleaning agents to soften water and for preventing pipe/boiler tube corrosion.

- Phosphorus is widely used to make organophosphorus compounds, through the intermediates phosphorus chlorides and the two phosphorus sulfides: phosphorus pentasulfide, and phosphorus sesquisulfide. Organophosphorus compounds have many applications, including in plasticizers, flame retardants, pesticides, extraction agents, and water treatment.

- Phosphorus is also an important component in steel production, in the making of phosphor bronze, and in many other related products.

- White phosphorus is used in military applications as incendiary bombs, for smoke-screening as smoke pots and smoke bombs, and in tracer ammunition.

- Red phosphorus is essential for manufacturing matchbook strikers, flares, safety matches, pharmaceutical grade and street methamphetamine, and is used in cap gun caps.

- Phosphorus sesquisulfide is used in heads of strike-anywhere matches.

- In trace amounts, phosphorus is used as a dopant for N-type semiconductors.

- 32P and 33P are used as radioactive tracers in biochemical laboratories (see Isotopes).

Biological role

Phosphorus is a key element in all known forms of life. Inorganic phosphorus in the form of the phosphate PO43- plays a major role in biological molecules such as DNA and RNA where it forms part of the structural framework of these molecules. Living cells also use phosphate to transport cellular energy via adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Nearly every cellular process that uses energy obtains it in the form of ATP. ATP is also important for phosphorylation, a key regulatory event in cells. Phospholipids are the main structural components of all cellular membranes. Calcium phosphate salts assist in stiffening bones.

An average adult human contains a little less than 1 kg of phosphorus, about 85% of which is present in bones and teeth in the form of apatite, and the remainder inside cells in soft tissues. A well-fed adult in the industrialized world consumes and excretes about 1-3 g of phosphorus per day in the form of phosphate. Only about 0.1% of body phosphate circulates in the blood, but this amount reflects the amount of phosphate available to soft tissue cells.

In medicine, low phosphate syndromes are caused by malnutrition, by failure to absorb phosphate, and by metabolic syndromes which draw phosphate from the blood or pass too much of it into the urine. All are characterized by hypophosphatemia (see article for medical details). Symptoms of low phosphate include muscle and neurological dysfunction, and disruption of muscle and blood cells due to lack of ATP.

Phosphorus is an essential macromineral for plants, which is studied extensively in soil conservation in order to understand plant uptake from soil systems. In ecological terms, phosphorus is often a limiting nutrient in many environments; i.e. the availability of phosphorus governs the rate of growth of many organisms. In ecosystems an excess of phosphorus can be problematic, especially in aquatic systems, see eutrophication and algal blooms.

History

Phosphorus ( Greek phosphoros was the ancient name for the planet Venus, but in Greek mythology, Hesperus and Eosphorus could be confused with Phosphorus) was discovered by German alchemist Hennig Brand in 1669 through a preparation from urine, which contains considerable quantities of dissolved phosphates from normal metabolism. Working in Hamburg, Brand attempted to distill some salts by evaporating urine, and in the process produced a white material that glowed in the dark and burned brilliantly. Since that time, phosphorescence has been used to describe substances that shine in the dark without burning.

Phosphorus was first made commercially, for the match industry, in the 19th century, by distilling off phosphorus vapor from precipitated phosphates heated in a retort. The precipitated phosphates were made from ground-up bones that had been de-greased and treated with strong acids. This process became obsolete in the late 1890s when the electric arc furnace was adapted to reduce phosphate rock.

Early matches used white phosphorus in their composition, which was dangerous due to its toxicity. Murders, suicides and accidental poisonings resulted from its use. (An apocryphal tale tells of a woman attempting to murder her husband with white phosphorus in his food, which was detected by the stew giving off luminous steam). In addition, exposure to the vapours gave match workers a necrosis of the bones of the jaw, the infamous " phossy jaw." When a safe process for manufacturing red phosphorus was discovered, with its far lower flammability and toxicity, laws were enacted, under a Berne Convention, requiring its adoption as a safer alternative for match manufacture.

The electric furnace method allowed production to increase to the point where phosphorus could be used in weapons of war. In World War I it was used in incendiaries, smoke screens and tracer bullets. A special incendiary bullet was developed to shoot at hydrogen-filled Zeppelins over Britain (hydrogen being highly inflammable if it can be ignited). During World War II, Molotov cocktails of benzene and phosphorus were distributed in Britain to specially selected civilians within the British resistance operation, for defence; and phosphorus incendiary bombs were used in war on a large scale. Burning phosphorus is difficult to extinguish and if it splashes onto human skin it has horrific effects (see precautions below). People covered in it have been known to commit suicide due to the torment.

Today phosphorus production is larger than ever. It is used as a precursor for various chemicals, in particular the herbicide glyphosate sold under the brand name Roundup. Production of white phosphorus takes place at large facilities and it is transported heated in liquid form. Some major accidents have occurred during transportation, train derailments at Brownston, Nebraska and Miamisburg, Ohio led to large fires. The worst accident in recent times was an environmental one in 1968 when phosphorus spilled into the sea from a plant at Placentia Bay, Newfoundland.

Spelling and etymology

According to the Oxford English Dictionary the correct spelling of the element is phosphorus. The word phosphorous is the adjectival form of the P3+ valency: so, just as sulfur forms sulfurous and sulfuric compounds, phosphorus forms phosphorous compounds (see e.g. phosphorous acid) and P5+ valency phosphoric compounds (see e.g. Phosphoric acids and phosphates).

Precautions

Organic compounds of phosphorus form a wide class of materials, some of which are extremely toxic. Fluorophosphate esters are among the most potent neurotoxins known. A wide range of organophosphorus compounds are used for their toxicity to certain organisms as pesticides ( herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, etc.) and weaponized as nerve agents. Most inorganic phosphates are relatively nontoxic and essential nutrients. For environmentally adverse effects of phosphates see eutrophication and algal blooms.

The white phosphorus allotrope should be kept under water at all times as it presents a significant fire hazard due to its extreme reactivity with atmospheric oxygen, and it should only be manipulated with forceps since contact with skin can cause severe burns. Chronic white phosphorus poisoning leads to necrosis of the jaw called " phossy jaw". Ingestion of white phosphorus may cause a medical condition known as "Smoking Stool Syndrome".

When the white form is exposed to sunlight or when it is heated in its own vapour to 250°C, it is transmuted to the red form, which does not phosphoresce in air. The red allotrope does not spontaneously ignite in air and is not as dangerous as the white form. Nevertheless, it should be handled with care because it reverts to white phosphorus in some temperature ranges and it also emits highly toxic fumes that consist of phosphorus oxides when it is heated.

Upon exposure to elemental phosphorus, in the past it was suggested to wash the affected area with 2% copper sulfate solution to form harmless compounds that can be washed away. According to the recent US Navy's Treatment of Chemical Agent Casualties and Conventional Military Chemical Injuries: FM8-285: Part 2 Conventional Military Chemical Injuries, "Cupric (copper(II)) sulfate has been used by U.S. personnel in the past and is still being used by some nations. However, copper sulfate is toxic and its use will be discontinued. Copper sulfate may produce kidney and cerebral toxicity as well as intravascular hemolysis."

The manual suggests instead "a bicarbonate solution to neutralize phosphoric acid, which will then allow removal of visible WP. Particles often can be located by their emission of smoke when air strikes them, or by their phosphorescence in the dark. In dark surroundings, fragments are seen as luminescent spots." Then, "Promptly debride the burn if the patient's condition will permit removal of bits of WP which might be absorbed later and possibly produce systemic poisoning. DO NOT apply oily-based ointments until it is certain that all WP has been removed. Following complete removal of the particles, treat the lesions as thermal burns." As white phosphorus readily mixes with oils, any oily substances or ointments are not recommended until the area is thoroughly cleaned and all white phosphorus removed.

Further warnings of toxic effects and recommendations for treatment can be found in the Emergency War Surgery NATO Handbook: Part I: Types of Wounds and Injuries: Chapter III: Burn Injury: Chemical Burns And White Phosphorus injury.

DEA List I status

Phosphorus can reduce elemental iodine to hydroiodic acid, which is a reagent effective for reducing ephedrine or pseudoephedrine to methamphetamine. For this reason, two allotropes of elemental phosphorus—red phosphorus and white phosphorus—were designated by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration as List I precursor chemicals under 21 CFR 1310.02 effective November 17, 2001. As a result, in the United States, handlers of red phosphorus or white phosphorus are subject to stringent regulatory controls pursuant to the Controlled Substances Act in order to reduce diversion of these substances for use in clandestine production of controlled substances.